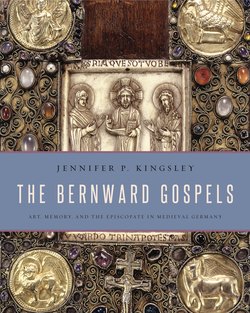

Читать книгу The Bernward Gospels - Jennifer P. Kingsley - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

An early eleventh-century painting assimilates Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim to John the Evangelist, Moses, and Jerome (DS 61, fol. 1r; fig. 1).1 The miniature introduces the only known illustrated Bible made for an Ottonian patron and layers traditional motifs in ways that produce a startling image. A large golden cross dominates the painting; it is flanked by two individuals, a man on the left, and a woman on the right. The cross’s monumental size and the picture’s composition invite comparison with Crucifixion imagery and suggest that the two figures are to be identified as the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist. Yet the cross appears inside a church, and its form is that of a work of art, an elaborately wrought processional cross. The placement of the two figures, John on the left and Mary on the right, reverses the usual arrangement, while their pose draws on donation imagery. John presents a book into which he writes the opening words of Genesis: “in principio creavit Deus coelum et terram.” Mary stands behind a curtain and gestures her acceptance of that gift. These details suggest that John serves as a stand-in for the episcopal patron, Bernward, who offers his Bible to the saint, making the image a kind of donor portrait. The inscribed text adds a further complication. While the first two words of the inscription echo the beginning of John’s gospel, “in principio erat verbum,” the complete phrase assimilates John and the patron either to a strangely youthful Moses, the author of Genesis, or to Jerome, the translator of the Bible.2

It is probable that a patron as well versed in the conventions of pictorial imagery as Bernward would have considered the male figure to represent his own image and all three models—John, Moses, and Jerome—simultaneously. There are many medieval precedents for comparing an individual patron to a series of exemplars of Christian virtue.3 What is unusual in this painting, however, is both the degree to which the miniature conflates multiple types of scenes and the specific combination of models it selects. These scenes (the Crucifixion and a donation) and these models (John, Moses, and Jerome) are not commonly associated in medieval culture. Such complicated layering typifies Bernward’s artistic commissions, from the manuscripts to the monumental works for which he is still best known: doors and a column that represent the most complex bronze-casting project since antiquity. Although these first gained fame as examples of the medieval response to classical art and of Bernward’s interest in ancient Rome (in connection with the notion of an Ottonian imperial renovatio focused on continuing the Roman Empire), more recent research has drawn attention to the theological ideas that inform Bernward’s choice of medium.4

The painting’s content similarly underscores the extent to which the bishop’s artistic patronage engaged sophisticated theological questions; it also makes somewhat problematic the picture of Bernward as a prelate whose career primarily exemplifies the administrative, jurisdictional, or secular features of the early medieval episcopate.5 Certainly Bernward was the grandson of a count palatine in Saxony who began his service in the imperial chapel as a notary.6 Quickly winning favor at court, Bernward became tutor to the future Emperor Otto III before being awarded, in 993, what was in essence a family bishopric.7 He proved an able administrator, asserting episcopal control over both diocesan property and tithes, building defensive walls around the town, and exercising a rare privilege to mint coins.8

Complicating the portrait of a bishop largely engaged by what we might term secular affairs, however, is evidence of Bernward’s interest in the monastic reforms that had been emanating from Gorze and Trier since the early tenth century.9 Bernward’s medieval biographers revise our image even further. In a text compiled in the twelfth century, they render the bishop as a man absorbed by the artes mechanicae, the “mechanical arts” of the medieval craftsman:

And although he embraced ardently all liberal sciences with the fire of his vivacious genius, he also found time for the study of those less serious arts that are called mechanical. His handwriting was excellent, his painting accomplished. He excelled also in the art of casting metal and of setting precious stones, and in architecture, as afterward became evident in the many structures he built and adorned sumptuously.... Painting and sculpture and casting and goldsmith work and whatever fine craft he was able to think of, he never suffered to be neglected. His interest went so far that he did not let pass by unnoticed whatever rare and beautiful piece he could find among those vessels from overseas and from Scotland, which were being brought as gifts to the royal majesty.... He attracted gifted boys to him and to the court and spent much time with them urging them to acquire by practice whatever was most needful in any art.... He also taught himself the art of laying mosaic floors and how to make bricks and tiles.... 10

Only the still more mythical stature of Abbot Suger of Saint Denis (1081–1151) rivals this image of a courtier bishop acting as a major patron, collector, and skilled artisan.11

Such varied pictures of Bernward illustrate the extent to which bishops of the early Middle Ages were pulled continuously in manifold directions.12 Bernward’s painted portrait suggests, however, that even the broad range of activities and responsibilities presented by the textual record fails to capture the full extent of how individual prelates themselves constructed their roles in early medieval society, how they manifested their presence, expressed their authority, and depicted their person.13 By manipulating pictorial conventions of representation, the portrait in Bernward’s Bible aims at conveying something of the bishop as both an individual and an office.14 Its layering of highly varied personas—Moses, the prophet and leader who brought God’s Law to the people of Israel; Jerome, the ascetic scholar who translated the Bible; and John the Evangelist, the deified theologian venerated in the Middle Ages for his visionary insight—develops a striking image of Bernward as a leader, scholar, and theologian. The painting consequently raises critical questions about the image of the Ottonian episcopacy. How did the early medieval bishop frame his varied responsibilities and actions? How did he portray himself and his office to the court, to his peers, to his flock, to God? What are the implications of Bernward’s self-fashioning—by visual means—for our understanding of the early medieval episcopate?15

Forming one of the most important networks for cultural production and exchange during the tenth and eleventh centuries, Ottonian prelates seem especially preoccupied with projecting themselves into contemporary visual culture.16 Bernward himself has left such a clear personal stamp on the (mainly) liturgical objects produced under his direction that these have been grouped under the term “Bernwardian art.”17 Among these celebrated works, one stands out in particular: the manuscript known to German scholars as the “most precious Gospels” of Bernward of Hildesheim (DS 18). Although the codex has been the subject of art-historical inquiry since the nineteenth century, many questions remain about its illustrations, including the meaning of its miniatures both individually and as parts of a program.18 This study argues that the Bernward Gospels pictorial cycle aimed to condition how contemporary and future viewers would understand the bishop’s role in Hildesheim. It thereby offers a unique witness to the self-presentation of this prominent representative of the Ottonian episcopacy.

THE CODEX

The Bernward Gospels measures approximately 280 × 200 mm and consists of 234 folios of vellum bound into thirty-three quires.19 Consistent peculiarities in the script help attribute the book’s writing to a single scribe working in Hildesheim from about 990 to 1020.20 The text consists of the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, with the preliminary matter proper to each (prefaces and chapter lists).21 At the beginning of the book (fols. 3v–9r) appear three out of the four standard Jerome prefaces, excluding the letter to Eusebius that starts “Ammonius quidem.” The number and order of these prefaces are shared by several Saxon manuscripts, of which some are attributed to Hildesheim and others to the imperial abbey of Corvey.22 A list of pericopes for the use of Saint Michael’s monks concludes the work (fols. 218v–231r); it notes the readings for the main feasts of the liturgical year. The pericopes’ inclusion suggests the manuscript’s potential function as a service book.23

With its peculiar combination of visual sophistication and naïveté, full of dramatically gesturing figures and covered in the saturated colors of densely ornamented surfaces, the Bernward Gospels is the most extensively decorated of the manuscripts produced for Bernward. Its decoration begins with a minium drawing that depicts Matthew as his symbol, the angel; a dedicatory painting follows. The codex also includes four author portraits of the evangelists, four title pages featuring elegant lines of Roman capitals, and one to two densely ornamented incipit pages per gospel—relatively standard fare for gospel books. More idiosyncratic are the twenty-four miniatures inserted into the codex that illustrate scenes from the New Testament.24 The pictures are organized into four groups, each designed to introduce one of the gospels, yet their presence frequently disrupts the physical structure of the codex.

An analysis of the manuscript’s codicology indicates the following collation: 12, 28, 36, 4–52, 6–158, 16–1710, 18–208, 216, 22–248, 252, 26–328, 332 (see fig. 2 and appendix). Irregularities occur in all of the quires that contain paintings. The miniatures disturb the organization of the text throughout the manuscript and clearly created a challenge for the manuscript’s binder. Particularly infelicitous is the arrangement of the seventeenth, twenty-fifth, and twenty-sixth quires, which contain illustrations for the gospels of Luke and John, respectively.

The New Testament scenes in Luke form part of the seventeenth quire; these appear on the recto and verso of the second bifolium, marked today with the numbers 111 and 118. The first illuminated folio (fol. 111) interrupts the gospel’s chapter list (fols. 110 and 112–116), while a second group of pictures (on fol. 118, the other half of the bifolium) appears between the gospel’s incipit page and illuminated initial (fols. 117 and 119, respectively). The paintings’ location thus leaves the two sets of pictures separate from each other even though they are painted on the same piece of vellum. It also means that the gospel text is interrupted. The problem stems from the attempt to add a painted bifolium into the gospel of Luke at a relatively logical point in the text—somewhere between the prefatory material and the main text—where the scribe had not allowed for it with any quire break.

The binder faced similar difficulties with the gospel of John. He responded by inserting the bifolium of figural scenes as an independent codicological unit that now forms the twenty-fifth quire (fols. 174–175). Consequently, all these miniatures appear in uninterrupted sequence. Yet they mark the shift from the gospel of Luke to that of John, appearing where we would expect to find the gospel’s prologue; this prologue actually starts on the following, twenty-sixth, quire (fol. 176r–v). The title page (fol. 178v) and illuminated incipit (fol. 179r) also form part of that quire. They follow the prologue to John and are thus separate from the rest of the gospel’s decoration. Again the binder seems to have worked unsuccessfully to organize a sequence as close as possible to a decorative scheme found in many Saxon gospel books, one that consists of an evangelist’s portrait followed by a title page and illuminated incipit. This sequence is disrupted because of the need to accommodate the additional historiated bifolia.

Writing about the Bernward Gospels in 1909, Hans Heinz Josten assumed its codicological irregularities occurred during a later rebinding, while more recently Rainer Kahsnitz has attributed them to the first binding, citing the Hildesheim scriptorium’s inexperience with elaborate picture cycles as their cause.25 Indeed there is evidence from the book covers of a twelfth-century intervention in the binding of the Bernward Gospels.26 Yet several aspects of the codex’s physical appearance suggest that the plans for the Bernward Gospels changed during the course of its production, allowing it to expand from a modestly decorated work into a more ambitious and eclectically illustrated codex filled with unusual iconography.

Codicological irregularities, likely already present in the first binding of the leaves, are due to a decision to expand the pictorial program at some point during production. If we remove the inserted painted bifolia from consideration and examine only the quires that include both decorated pages and plain text, the layout would allow for two to three sides of paintings between each gospel’s prefatory material and main text. This arrangement would have accommodated at least an author portrait and one to two title pages, which is consistent with the arrangement in other manuscripts produced at Hildesheim, such as the Guntbald Gospels (Hildesheim, DS 33), ca. 1011, and the Hezilo Codex (DS 34), variously dated to the late tenth or early eleventh centuries; it would also agree with the design of a group of closely related gospels produced in Corvey.27 In this hypothetical layout, the decoration for Matthew, Mark, and Luke would start in each case at the end of a quire (quires 3, 12, and 17; fols. 15, 75, and 117), while the paintings for Luke would still appear within quire 17 (fol. 117v). Quire 17 would have the more usual (for the Bernward Gospels) eight leaves, or four bifolia, instead of the current ten.

Because of the organization of the textual quires, adding the painted bifolia to the codex allows for only two possible binding schemes. The first option involves gathering the narrative scenes into a single quire, which would, however, separate these paintings from the author portraits and decorated text pages. The second option requires the bifolia to be inserted as close as possible to the prefatory material of each gospel, even where it means interrupting the text. The placement of the illustrations for the gospel of Mark suggests that the scriptorium chose the second solution and adopted it before completing the miniatures but after laying out the text. The miniatures in Mark appear not on independent bifolia but as an integral part of quires 12 and 13; each painted leaf therein is one part of a bifolium that has text on its other part and, as with the bifolia inserts, the paintings appear in the following sequence: first narrative scenes, then an author portrait, and finally, decorated title pages.

What of the possibility that the codicological irregularities stem from the scriptorium’s inexperience working with narrative picture cycles? The scribe may have been using a model that had only limited decoration, and, tasked with incorporating a full pictorial program into the Bernward Gospels, may not have known how to modify the codex’s layout to accommodate more paintings. Yet before making the Bernward Gospels, the Hildesheim scriptorium had already produced the Guntbald Gospels in a very regular layout of quires of eight leaves that allowed five sides to illustrate each gospel; in its present irregular arrangement, the Bernward Gospels also has five to six sides available to illuminate each gospel. If the Bernward Gospels had been intended to carry an extensive pictorial cycle, a suitable model for its current appearance already existed in Hildesheim.

The strongest evidence that the plans for the pictorial program evolved during the manuscript’s production is the full-page drawing that currently opens the pictorial cycle in Matthew (fol. 15r; fig. 3). The picture conflates the evangelist Matthew with his symbol and occupies a shorter but wider pictorial field than the other illustrations of the manuscript; unlike those, it also lacks a frame. The drawing’s composition differs substantially from the painted portraits of the evangelists (fols. 19r, 76r, 118v, and 178v; plates 6, 9, 13, and 17). Each of these is portrayed in the lower half of a divided pictorial field. The drawing’s style is both looser and more three-dimensional than that of the paintings, particularly in the modeling of drapery and the depiction of objects that recede in space. It clearly belongs to a different decorative scheme than the one ultimately chosen for the Bernward Gospels.28

If the design of the Bernward Gospels changed during its making, it evolved from a modest and somewhat conventional plan, modeled in large part on manuscripts produced in the imperial abbey of Corvey, into a fully illustrated New Testament cycle drawing on a wide variety of sources.29 The designer at that stage incorporated contemporary iconography and ornament that originated in diverse places ranging from medieval Wessex to Constantinople. To date, the account of the sources for the miniatures has tended to treat examples of copying in the manuscript as the passive transmission of models.30 Yet the Bernward Gospels displays several examples of unique iconography, some of which, such as the theologically complex depiction of the Ascension that shows Christ literally disappearing from view (fol. 175v; plate 17), first appear in the tenth century and/or constitute the earliest example of that particular iconography in Ottonian art.31 This suggests the presence of an active interest in contemporary developments in both art and theology. The most probable impetus for that interest is the patron, Bernward. He is the one historical person securely connected to the manuscript who was demonstrably familiar with the Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Byzantine art that so profoundly influenced the Bernward Gospels pictures.32

The patron undoubtedly played a formative role in the book’s design.33 From the disappearing Christ inside the manuscript to the standing Virgin carrying a palm on the back cover, a number of iconographic motifs in the manuscript stem from sources to which a painter in Hildesheim was unlikely to have had access. Iconography is something that would be relatively easy for a patron to communicate to an artist. In contrast, the ornament and style of the Bernward Gospels derive primarily from Carolingian manuscripts that the weight of the evidence suggests were physically present in Hildesheim, from codices produced in Corvey that seem to have passed through Hildesheim, and from Byzantine silks that were at that time part of the cathedral’s treasury. All of these would have been locally available to the artist(s) as models.34

Moreover, the manuscript’s pictorial program offers no one-to-one relationship between the manuscript’s illuminations, the gospel text, or specific exegetical commentary on the gospels. For example, although Mark describes Christ’s Ascension in detail, it is depicted as the concluding picture in the book of John (fol. 175v; plate 17), and although John is the singular source for the so-called Noli me tangere, that scene illustrates the gospel of Mark (fol. 75v; plate 8). The Crucifixion appears twice in the manuscript, both in the gospel of John (fol. 175r; plate 16) and above the portrait of the evangelist Luke (fol. 118v; plate 13). The cycle also presents scenes out of their narrative sequence. Together, these elements suggest idiosyncratic choices made to develop particular themes, themes that over and over again engage complicated theological questions, especially about the nature of Christ and man’s perception of that nature. What are the themes of the pictorial program, and what may have prompted their introduction into the Bernward Gospels?

PICTURING THE BISHOP

The manuscript was produced for the community of Saint Michael’s Abbey, located just outside the town walls of Hildesheim, about five hundred meters north of the cathedral.35 Verses in Bernward’s own hand record the donation (fol. 231v):

I, Bernward, had this codex written

and, ordering that my wealth be added above, as you see

I had surrendered [it] to Saint Michael, beloved of the Lord

Let there be a curse of God on anyone who takes it from him.36

Although the complex would be completed under the bishop’s successor, Godehard, Bernward consecrated the monastic church’s crypt altar in September 1015; he designated the same area as the site for his burial. Bernward also dedicated the unfinished building shortly before his death in 1022. The Bernward Gospels may have been presented to the monks at the occasion of one of these consecrations, and its expanded program was probably conceived around 1015.37

Indeed, the book served as one of the bishop’s founding gifts to the monastery, a project and bequest Bernward remembers in a document from November 1019 as a vivid struggle against time.

The succoring mercy of God finds its expression in the human longing for grace, and adapts itself to the individual person. If we look for examples of this we immediately find a divine answer: after Adam’s fall and the long age of exile Abraham believed the Lord, and precisely that was counted to him for righteousness. By contrast, Moses, who gave the Law, became a leader and teacher of the people of Israel both by God’s outreaching grace and through his own merits. And Elijah, worker of miracles, gave evidence of a similar holiness.... Clear as daylight is the evidence of the holy Solomon, who after building the temple of God, cleansed himself in accordance with the laws of his religion and brought himself closer to God by participating in cultic mysteries, he who was found to be without equal as a penitent. To all of them God revealed the special nature of their merits through their respective manner of deeds, so that in time they will remain different from all others, always, by virtue of merit and deed, and in eternity they will be equal to the angels.

In view of this I, Bernward, appointed bishop by God’s election and not of my own merit, have long given thought to how I, learned court clerk, tutor and keeper of documents for Emperor Otto III of blessed memory, might be deserving of heaven, by what architecture of merit, by what achievement[.... ]

Then, having ascended the throne of the church of Bennopolis, I wanted to carry out in deed that which I had long been planning in my heart, that is, I wanted to prepare a felicitous memorial to my name as someone who had built churches, instituted the service of God in them and donated all his possessions to the Lord. Now God’s decrees are hidden but always just. I therefore began, with the joyous consent of the faithful, to construct a new house of God, and in so doing both fulfilled my own promise and served the best interests of Christendom, to the praise and glory of the name of the Lord, by settling monks there who were beloved of God. However, when the foundations of the building had been laid, and the outlines of the individual rooms were already visible, I was stricken with fever and was ill for five years[.... ] But since nothing on earth occurs without a reason, I believe and trust that the Lord was correcting me with his chastisements, yet he did not deliver me unto death, and thus prevented the work of my hope from being interrupted by my absence. I caused monks to occupy this place, which was dedicated to God, the holy cross, the ever pure Virgin Mary and the holy archangel Michael. I united them here according to the principle that, being removed from the activity of this world as laid down in the rule of monks, they might be free of all hindrances of worldly duties. Therefore, with the consent of the Lord and Emperor Henry and of my superior, the archbishop, I gave away everything I had inherited or acquired by my private means in worldly goods, estates, farms, lands, fields, pastures, waters, forests, meadows, churches, relics, books, gold, and silver, and whatever else there might be. Aside from what I bequeathed to the altar of the blessed Mary in the cathedral in the form of golden crowns, chalices, candlesticks, vestments and other ornaments, I made over everything by the hand of my testamentary guardian to God and his saints for the use and benefit of the brothers. I have bequeathed it for the salvation of my aforementioned Lords and Emperors, of myself and my successors, as well as of all those from whom I have acquired inheritances, so that the servants of Christ, free of all earthly duties, secure in the protection of my successors, may enjoy peaceful times and devote themselves to the life of pious contemplation for the salvation of all men.38

It is tempting to read in this text something personal about Bernward’s artistic projects during the period from the laying of the abbey’s foundation in 1010 through the probable duration of his illness (1013–18).39 The bishop’s account suggests a patron suffering for years from an inexplicable and recurrent disease who is anticipating his own death, worrying about his sins and driven to show himself worthy of salvation.

Whether or not Bernward’s illness directly influenced the decoration of the Bernward Gospels, his testament goes further than those of other founders in its religious aspirations, and many of its themes—especially the evocation of models who have realized divine election as saints by means of their own merit—are reflected in the codex’s program. The document also evokes medieval ideas about gift-giving pro anima (for the soul) with its related expectations for intercessory prayers and liturgical commemoration.40 That process was structured around the idea that mankind might gain eternal rewards by making offerings to the divine. The gift pro anima is thus fundamentally preoccupied with the donor’s salvation, and it is surely no accident that the only Christological miracle depicted in the Bernward Gospels is the Raising of Lazarus (fol. 174v; plate 15), a story that functioned in medieval commentary as a topos for Christ’s Resurrection and therefore an eschatological promise that the dead would rise again in their flesh to be judged by God at the end of time.41

The success of the medieval gift pro anima and its salvific power depended on the earthly recipients’ commemoration of the donor and the capacity of the object to carry his memory even after death.42 To that purpose, the Bernward Gospels engages the praxis of memoria, the multivalent medieval term for memory that suggests equally the cognitive processes of mnemotechnics and the ritual habits of commemorative practices.43 The codex draws on the cognitive and ritual processes of both in order to decorate an object of particular symbolic power: the gospels, displayed on the altar in order to be venerated as the Word of God made flesh, namely, the incarnate Christ.44

The dedicatory bifolium in the Bernward Gospels starts at the point where gift-giving pro anima, salvation, and memoria intersect. Placed after the codex’s prefatory material (fols. 16v–17r; plates 2 and 3), the painting serves as frontispiece and key to the manuscript’s pictorial program.45 It is the starting point for this study and the subject of the first chapter. The painting translates a well-known medieval textual formula, the treasury list, into pictorial form. The resulting display of accumulated wealth underscores the actual and symbolic value of the pictured treasury, adding to the book’s efficacy as a gift pro anima. The painting simultaneously emphasizes the role of artworks as portals and material hosts in a process modeled on the entry of spirit into matter that takes place during the consecration of the Eucharist. The painting’s capacity to project the donor’s image into memory depends on the capacity of objects to bridge the distance between earth and heaven.

While the dedicatory painting argues for the power of objects, and thus of the manuscript itself, to prove the donor’s merits and carry his memory, the succeeding illuminations in the Bernward Gospels help shape how he is to be remembered. Their study is at the heart of this project’s examination of the bishop’s self-presentation, and they are the subject of the second through fourth chapters. These develop two main and interconnected themes. The second chapter considers the presentation of varied forms of service. While one aspect of this theme involves the dissemination of the Word more generally, a series of paintings that illustrate the life of John the Baptist develops an argument more specific to episcopal concerns; these emphasize the merits of the vita activa that characterizes the priesthood.

A second important theme of the Bernward Gospels is the spiritual perception of God and the desire to unite with Him, which the pictorial program develops in two related groups of miniatures that each focus on a different sense, sight and touch. Chapter 3 investigates a series of pictures in the Bernward Gospels characterized by a representational tendency that is static, frontal, hieratic, and symmetrical; these miniatures treat the nature of corporeal and spiritual sight both by representing vision and by directing the visual experience of the paintings. Chapter 4 focuses on a group of miniatures that present figures engaged in narrative action involving the tactile experience of Christ. These explore connections between the saints’ handling of Christ as a human body and the haptic experience of art itself as a Christological body.

In the exploration of these two sensory modes, the paintings again use John the Baptist to link the patron to models of spiritual perception. Among the many roles ascribed to John the Baptist in the Middle Ages was that of visionary witness, and he appears in the Bernward Gospels as one of the group of saints who share a particular power to penetrate the mystery of Christ’s dual nature with their spiritual sight. The Bernward Gospels also presents him, highly unusually, as one of the series of figures privileged to come into direct, tactile contact with Christ. As an exemplar for both senses, the optic and the haptic, the model of the Baptist shapes Bernward’s portrait as a figure both inspired and worthy of salvation. By means of his sight and touch, the bishop approaches his hoped-for eternal reward.

Despite its often unusual imagery, the Bernward Gospels shares some affinities with contemporary representations of both historical bishops and bishop-saints. At a time (before the Gregorian reform) when they were still relatively independent actors in both ecclesiastical and secular hierarchies, bishops pursued agendas determined by their particular historical circumstances. Yet they also shared concerns stemming from the nature of their office, their role in the Church, and their administrative responsibilities. These concerns shaped not only how bishops presented themselves but also how hagiographers constructed the memory of episcopal saints. By examining both the idiosyncratic and more conventional aspects of the episcopal image in the Bernward Gospels, this study considers how a prominent representative of the Ottonian episcopate understood and presented both himself and his office in the early Middle Ages.