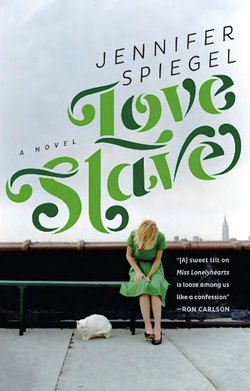

Читать книгу Love Slave - Jennifer Spiegel - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеGOING HOME WITH THE POETS

New York City on Sunday, December 11, 1994

Madeline and I are walking home from the Nuyorican Poets Café, where these people with lousy day jobs, like waitressing or temping or sometimes dealing, read their poems, which are always about having really good sex or being a black woman.

We go there on Friday nights, always Friday nights, and we fold our legs beneath us on wooden floors, sipping cheap drinks and sweating under bare bulbs that make the place look ghoulish.

Next to us, the poets. Ahh, the poets! People of mystery, of magic, of words. We know they write quatrains and couplets on paper napkins at cafés on Sunday afternoons, stirring lattes, buttering croissants, consuming raspberry tarts— oh, we envy them their free verse!

Madeline and I, two in the morning, eye makeup black and thick, walk fast because we're in Alphabet City, which is like a sub urb of the East Village but not really. We can handle the East Village freaks, but crack houses are another story.

Despite winter, I'm on fire— the kind of fire wrought by that rare and special combo of man and lyric together. Tonight, the poetry wasn't great— not great at all— but there was this one man, this one poet, a guy from Jamaica with dreadlocks, a black lanky body, and a somber long face. His poetry— sparse, unpretentious, not about being a poet— crawled over to me on the floor and punctured internal organs under a crystalline glare. It made me want to say something to him: anything.

In that moment, maybe like other moments before, I forgot my own paramour, my own backlash boyfriend, rarely present, rarely even imagined.

I forgot and no one reminded me, so I turned to this Jamaican poet with a searing, easy lust— I turned to him with famished, desperate eyes— and I listened to what people said: Teaches high school English in Brooklyn. A cab driver, a bard.

So I knew; I knew then he was both soulful and earthy.

I made my approach, touching his arm lightly. " Yours was the best."

He turned, his eyes lifting to mine, a honeyed Jamaican voice haunting his breath. "You are the only one who thinks so."

I do, I do, but I do.

It was like being thrown against the wall by a great gust of wind, and this is why I live in New York. This is why.

Now, walking fast with Madeline, I imagine this Jamaican poet/ Brooklyn high school English teacher and me owning a loft in TriBeCa. In our loft, there'd only be a mattress. The room would be strewn with sheets, white and gauzy, blowing in a breeze that sallied through open windows offering up the scent of city, skin, and naan bread from the Indian restaurant below.

I think about meeting the Jamaican poet on corners at nightfall, how he'd see me coming and I'd see him standing there with his I Don't Care body posture— that lovely, lanky I Don't Care body posture— which would briefly, fleetingly, shift to reveal his thrill at seeing me walking toward him. I'd stare into his sleepy sad Jamaican poet face, and I'd probably have to weep just for the beauty of his poet approach.

Madeline, the only thing I've kept from a long string of temp jobs, points to a torn poster on the wet ground. " Glass Half Empty is playing at the Fedora on Friday."

Glass Half Empty plays there monthly, and we go religiously because, we say, when we analyze the situation over coffee at a diner or a Village café, it makes us feel like we have a community, and we know from our private dwellings— our beds and the places we stand alone, places in front of Xerox machines and other instruments of capitalist alienation— that we have no community, no community at all.

And this is what I want, what I need, what I choose. I temp, my lust is fruitless as temp lust always is, and whomever I love today will not be the person I love tomorrow.

And so: we watch Glass Half Empty play. It's the repetition of action, the sanctity of ceremony, the joy of the familiar. We need it to make us believe we are alive. To prove we are, indeed, alive.

I heard from some girl at Yaffa Café that the singer's wife died a year after they married and he still, seven years later, wears his wedding ring around a swollen finger. Though some may find this morbid, I think it beautiful. Perhaps he understands what it means to have loved and lost. Perhaps he really understands.

This time, in my head, it's the singer and me.

We're on a shag carpet because Rob is rather retro— a throwback to a time never had. It's the shag carpet, a messy apartment, a pizza on the coffee table. He probably bought this coffee table at a sidewalk sale on the Lower East Side one Saturday afternoon, after wandering for hours and hours in search of used CDs by Buffalo Springfield and old paperback novels with prices like seventy-nine cents on upper right-hand corners.

He's my kind of man, as the elastic of his Scooby-Doo boxers surely attests. I'm certain I'd be far happier with Rob than with my beautiful Jamaican poet. The poet would want profundity, and I am simple.

Madeline lets out a yelp of disgust, an Ewhh! a Don't look now!

Of course, I turn my head to the steps of NYU's business school— the bane of my existence— and, here's what I see: some guy getting a blow job, the girl not even visible.

Must I be privy to this? Did anyone hear me ask for such a sight?

Madeline and I look straight ahead, walking fast until we're well into Greenwich Village, which is where I live in somebody's basement with a guy named Tom who can't stand the sight of me because I once freaked when he left the keys in the lock on the outside of the door overnight. But he's in Greece for a year studying the Pythagorean Theorem, and his dad pays his rent.

By now we're obsessed with this most recent vision on our otherwise pure evening.

I remember how my mom responded when I told her that, one balmy summer day, when I was walking on Twelfth, I saw this guy taking a dump right on the street— right in the middle of the street— and how she couldn't believe I chose this existence, and I tried to tell her this is my life.

Mom, this is my life.