Читать книгу Love Slave - Jennifer Spiegel - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

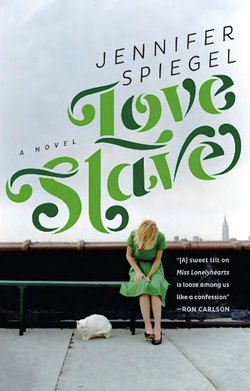

Three -New York Shock

ОглавлениеStill Saturday, January 7, 1995

Carefully, ever so slowly, the paper falls slack in Rob's lap. It curves over his knee. With grave seriousness, he reaches for my eyes with his. "Freaks keep you here?"

I look out the window. Greenwich Village looks cold, blustery. The brownstones across the way are beautiful, idyllic, atmospheric. Sometimes I imagine hardwood floors, stair banisters, dried flowers in vases, wood-block cutting boards in kitchens. A wine rack with reds and whites, a big dog, a four-poster bed, an excellent collection of jazz CDs. Sometimes I imagine myself walking down West Fourth pushing a baby buggy. A woolly scarf covers my mouth. The baby wears footed pajamas.

A man in pink barrettes and a fur coat enters to do his laundry. Kim says hi while Rob and I have this quiet question between us. In the background, Anne Murray sings, You needed me, you needed me.

"This is my last year in New York," I say. "I'm thirty. I don't want to be thirty-one here." Already, four wiry gray hairs refuse to play the game, refuse to take part in style.

"I'm thirty-one," he says. "It's fine." He uncrosses his legs. New York Shock settles into its new position.

"I can't do it; I can't grow old here." I watch the man in barrettes empty a duffel bag.

"Then why don't you leave tomorrow?" Rob's voice is sardonic and sharp. "Or today?"

I'm taken aback by the tone of his voice. I've got my reasons. I'm here to be alone, to accept my liabilities, my neuroses. New York City is my internal state of mind made external. Everything it is on the outside is what's going on in my inside. Plus, the freaks. Don't forget the freaks. But I have to leave; I'm losing sleep, becoming lonely inside my own head. I'll go to a new city or town. I'll hide away my sorrows in suburbia and do things like plant tomatoes, give Christmas gifts to the mailman, and watch the rising price of gasoline. When I leave, I'll be ready to be alone in the presence of others. I point to his copy of Shock. "I've got the column."

Rob Shachtley, lead singer of Glass Half Empty, purses his lips, waits a second, then says, "Huh." He opens Shock. There's a sidebar inside, a sidebar for me. He arrives at it with his fingertips. At the top of the page, it says "Antibiotics." Every week, readers send in letters about my column. He flicks his fingers against the words. "You're a splash. You generate the mail, babe."

"I figure I'll stick around till 1996. Then I can be one of those writers who lives in New England or has a farm somewhere. Or a ranch. In Sundance. Or Vail. Didn't Hemingway die in Idaho?"

He remains silent for a second, looks at Kim, and then turns to me again. "You're not making it by just writing a weekly New York Schlock column, are you? You don't think that's gonna get you a ranch in Sundance, do you?"

"I temp," I divulge.

He gets up to check his machine. "You meet lots of struggling actors and actresses on the temping front?"

"Never. They all cater." I walk over to my washer. "What's the most interesting thing that's ever happened to you on the job?" Manhattan fodder for writers seeking the absurd.

Rob balances on the balls of his feet. "Once I catered a dinner at Kissinger's."

"Fascinating man," I say.

"Rack o' lamb with new potatoes. Rosemary something."

I squint, picturing it. "If at all possible, I'd avoid serving lamb."

"Old rich guys love it." Rob's machine stops spinning. These washers wind down without warning. No plaintive cry for attention, no wailing buzz, nothing. He starts the dance that takes place between washer and dryer. Nothing must touch the ground or it's over: you lose. "What's the most interesting thing that's happened to you while temping?"

I put my hands on my hips. "Wait— was it Kissinger or the lamb that was interesting?"

Rob holds wet pants in his hands and then whips them into the air to shake out creases. "The whole milieu, I guess." He exaggerates the pronouncement of milieu, moving his lips dramatically over its syllables. "The home, the study, the formality, the aura of the Cold War— not to mention the lamb." He decides to dry the pants after all, so he shoves them into the mouth of the appliance. "I'm not sure anyone was aware that the Soviet Union was now Russia, or that the Iron Curtain came down."

"I'm impressed by your use of the word milieu."

"Make your own assumptions." He shrugs. "Your turn. Temping adventure?"

Back in my plastic chair, I swing my feet across the dirty floor like a kid. "Once I worked with a woman who was absolutely paranoid about her silicone breasts."

"This sounds good— I love breasts."

"Silicone ones?"

"They make me a little nervous," he admits, digging into his pocket for quarters.

"She was terrified that the end of the world would arrive— you know, the Apocalypse— and she'd be forced to flee to the mountains like the singing Von Trapps."

Rob walks over to me. "It could happen—"

"She said her biggest fear in life was that one silicone breast would collapse while she lived in the hills, and she'd be stuck with one perky and one deflated breast."

"Interesting visual." Rob sits next to me, his eyes faraway.

"I told her not to worry."

Rob leans back in his plastic chair. "I wonder how she'd get to the hills." He closes his eyes. "Was she a camper? Did she like hiking?"

I know more about this man than I let on. Rob Shachtley was married at twenty-four and, within a year, his wife died from a brain tumor. Seven years later, he still wears a wedding ring. I'm talking to him now and he's wearing a gold band. He sings sad songs about a girl in the sunshine with corn-colored hair, standing near doorways and windows and other open things. He sings about how she always looks like her twenty-three-year-old self and, no matter what he imagines her doing, whether playing with their imaginary children or pulling nylons over her imaginary knees, she's always twenty-three. The sad songs become angry ones. He sings about how he's being deprived of her old age, how he'll never see it, and the very thought makes him ill.

Grapevine, word on the street, hard-core analysis of Glass Half Empty lyrics.

Also, he has a reputation for being a sleaze.

"So, when are you guys playing next?" I ask.

"Friday, the twentieth. At the Fedora. Ten p.m." He sits up straight.

"I'll be there. With my friend Madeline." I look at Rob, staring at his orange pants, his Roy Orbison glasses. Rob Shachtley, lead singer.

"Who's she?" He walks over to the dryers, oblivious to my thoughts. "What does she do?"

"She stuffs envelopes at a human rights organization by day, and she's an ESL teacher in Queens by night. She teaches English to Romanians newly off the boat."

"Do they still arrive by boat?" He reaches into a dryer to touch his clothes.

"I'm not sure." I fold my arms across my chest. "I'll have to check."

"Is she an artist?"

"She's a great dabbler in the arts, but she wants to write."

"Who doesn't? Another middle-class college grad turned loose on the streets of New York, right?"

I almost tear up. "Yeah, that's her."

He leans back against a hot dryer. His machine stops. "U Mass, Amherst, 1988. Ask me something about Shakespeare. Go on— do it." He opens his dryer. "So, Sybil," he says, sounding like a caricature of himself, "do you want to get together after the show?" He drags out his clothes and begins to fold them.

"What would that entail?" I stop suddenly. "I have a boyfriend."

He dramatically drops his head to his chest. "I knew there was something you were holding back. I can always tell when people have secrets—"

I quickly say, "But we could still do something after the show—"

"Like me, you, and him?" He scrunches up his face.

"Yeah. Or me, you, him, and Madeline. Or just you and Madeline and me. Or just you and me, but before the show. Don't ruin a perfectly lovely conversation—"

"You said I was divine."

"I meant it." I sit down again. I have one more spin cycle.

"Why before the show and not after?" Rob stuffs his laundry supplies into a laundry bag. He struggles with a winter jacket. He's getting ready to leave.

I look out the Laundromat window. "I don't know." I meet Rob Shachtley's eyes. "I'm not sure. It doesn't make any sense."

He stands in front of me, a laundry bag thrown over his shoul

der like Santa Claus about to deliver toys. "You want to be friends? Is that what you're saying? The Sybil Weatherfield of 'Abscess' wants to be my friend?"

I look at my hands. I feel small in my red sweatpants and old Doors t-shirt. "It's a brazen assumption." I'm embarrassed; he may be making fun of me. "I never suggest friendship with anyone. I haven't made a new friend in over two years. I spend all my time talking to office girls who are obsessed with their pets, many of them dead. I eat dinner on a TV tray and call it a night. I see movies alone, including Interview with the Vampire —"

"Enough!" Rob drops his laundry bag onto the floor. "I'll be your friend."

"Only if you want to," I add.

"Your name will be at the door on the twentieth." He bends over to pick up his bag. "You and guest. There are two weeks between then and now. That'll give me time to get over the fact that you're not interested in being my love slave. Or, it's time enough to dump the boyfriend."

Did he just say love slave? I think he did!

Rob Shachtley, widower at twenty-four, wearer of wedding ring binding him to a dead woman, moves outside. The door swings shut behind him. He raps on the glass above my head and draws a musical note with his finger on its dusty surface.

Then he walks away.