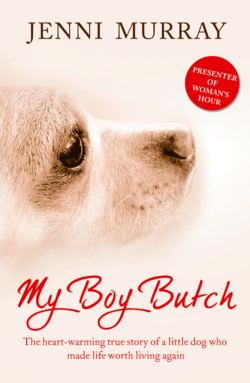

Читать книгу My Boy Butch: The heart-warming true story of a little dog who made life worth living again - Jenni Murray - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter One

A Dog Is for Life

There was always a dog. If not real, then imagined. I don’t precisely recall at what stage it began to dawn on me that the most powerless creatures on the planet seemed to be little girls, but I can’t have been much more than a toddler when I developed a deep resentment of being bossed about. It had quickly become apparent that I was considered fair game for parents, grandparents, disapproving aunts and the gang of local big boys who tittered at any valiant attempt to join in with climbing a tree, kicking a ball or steering a tricycle. They made it quite plain they would as soon drown in the dirty duckpond as be seen actually playing with a creature that jabbered incessantly and sported (generally unwillingly) a ribbon in its hair.

But a dog, I knew – partly by instinct, partly from the books my mother read to me – would never snigger or criticise or make demands. It would revel in your company and obey the most peremptory of barked orders. ‘Sit, heel, stay, roll over’ would be music to its ears. It would fetch the ball you were doomed to play with alone. Should you find yourself being beaten up by the biggest bully on the street – a not uncommon occurrence – it would tear out his throat in your defence. Should burglars dare to enter at the dead of night, it would rip out the seat of their pants and hold them, terrified, until the constabulary turned up.

In my vivid, infantile imagination I dubbed myself ‘the mistress’ and ceased to be some pathetic, undersized weakling, expected to sit nicely, knees demurely together with neatly brushed hair and scrubbed apple cheeks.

At night, after the bedtime story, I dreamt that a heroic Shadow the Sheepdog lay snoring at the end of my bed as I slept or Lassie traversed the known universe to be at my side or Timmy and I strode about solving crimes and saving damsels in distress.

I begged and pleaded with my mother for a dog of my own. She was adamant that she had quite enough to do, thank you very much, with a house, a child and a husband to run around after. Why would she need the responsibility of a dog?

‘I know full well,’ she’d say, ‘that you’ll tell me you’ll look after it. But you won’t. I’ll be left to walk it, feed it, and I’ll be hoovering all day to get rid of its hairs.’

My mother was obsessively houseproud and, although I doubt she realised it at the time, had indeed articulated one of the first lessons in the canon of feminist commandments:

‘Thou shalt not buy any animal you are not prepared to clean up after. Men and small children have a tendency to lie about their readiness to attend to such matters.’

Thus the lonely existence of an only child continued until the happy coincidence of two not entirely unconnected events. The first involved my disappearance. I was four. This was the 1950s and, apart from reading, listening to the wireless and being helpful around the house, there was not much to keep a child entertained at home.

Parents were relatively unconcerned about their youngsters playing out. In fact, for a mother whose work was staying home, cooking, cleaning, washing and ironing, it was something of a relief to have her offspring out from under her feet for an hour or two. There was none of today’s dire warnings of stranger danger, nor were there enough cars on the road for incessant traffic to be seen as much of a threat. There must have been a degree of parental concern as I was frequently warned not to ‘go off ’. ‘Stay in the garden or the fields or the street where I can keep an eye on you.’

Only, on the day of my disappearance, I was George – the best fictional role-model any growing girl could have and the star of my favourite Famous Five books by Enid Blyton. How I longed to have a name that could be made to sound like a boy’s, to show scant interest in the making of cakes and sandwiches and be the protagonist in whatever adventure I could conjure. Naturally, at my heel, would be the celebrated Timmy. I don’t recall that Timmy was ever held on a lead in the books, he simply ran along obediently by George’s side.

But I knew, whilst still a tiny girl, that even slow-moving traffic could cause devastation. A small boy, the son of a neighbour, had been killed not long before whilst playing under the Co-op grocery van. He’d been crushed as it pulled away and all of us who were used to playing in the street had seen the white, drawn faces of the mothers who comforted the one who had lost her child.

We had stood at our kitchen windows as the cortège with the tiny coffin had driven slowly down the road and had sobbed in sympathy with our own parents. I know now that people would think it silly to compare the threat to an imaginary dog with that of an all-too-real child, but to me, at my young age, the danger was genuine. I was so worried that during our long trip looking for thrills in the village Timmy might run into the road, I had his leash clutched in my hand.

We were gone for hours. We popped into the Co-op store and trailed our feet through the sawdust on the wooden floor, sniffing the pungent aroma of freshly ground coffee and watching the man in the white coat and cap slicing through the huge smelly cheeses with an enormous wire – scary, just like a guillotine. Then he’d cut through a ham with a whirring circular saw, leaning over the counter and asking whether my dog might like a taste. We said thank you, I scoffed the lot and we left and crossed the street to Tom the fruit and veg man who’d been kind enough to return a lost and beloved teddy I’d once left behind. He too welcomed Timmy and me and offered an apple. I declined, explaining that the dog wasn’t keen on fruit and I mustn’t as it was nearly teatime. We set off home, climbing the steep hill, tired by now, and hungry.

For years my mother would describe in exacting detail the moment she saw her diminutive daughter come at last into view, dragging a piece of string behind her and demanding, imperiously, ‘Come along, Timmy, don’t dawdle. We’ll be in terrible trouble if we’re late for tea.’ Until I had my own children, I never understood why mothers, who are hugely relieved at seeing their child safe and sound after long, anxious hours, shout, scream and are furious rather than huggy, kissy and nice. Very cross was what she was. Timmy and I were sent upstairs to my room in disgrace and with no tea. I think she must have sat in the kitchen thinking how much more sensible it would be, should I ever dare to disappear again, for me to be accompanied by a real dog who might provide some protection rather than by a useless figment of my imagination.

Which is when we had the visit from Cousin Winnie. She shared my mother’s Christian name and her penchant for upward mobility. She bred corgis with a pedigree as long as your arm in tacit emulation of the Royal Family. She had a problem. Her prize bitch had shown scant regard for the preservation of the blueness of her blood and had indulged in illicit relations with some mongrel mutt from the wrong side of the tracks. The resultant puppies were far from pure bred. She was having trouble getting rid of them and just wondered if we might be prepared to take one off her hands.

Thus, on my fifth birthday, I came down to breakfast and was given a parcel of irregular shape to open. It contained a collar and lead. The lead had a tag on which was engraved, not Timmy, but Taffy. A minor disappointment, but an acceptable nod in the direction of his half Welshness, and my parents led me by the hand, trembling with anticipation, to the shed outside.

There, lying nervously in a far from comfy plastic bed (easy to keep clean, said my mother; he won’t be in it for a minute, thought I, he’ll be snuggled up on my blankets) was everything I’d imagined Timmy/ Taffy to be. Gingery brown, huge, meltingly dark eyes, stiffly pointed ears, spindly legs and the longest, waggiest tail I could have hoped for. The mongrel genes had won out big time over the short-legged, stocky corgi. He hopped out of the bed, wriggled over to where I crouched on the ground and licked my hand. I knew I would never be lonely again.

Taffy turned out to be the fulfilment of every one of my childish canine fantasies. He was a willing and uncomplaining accomplice in any silly adventure in which I chose to involve him, mostly concerning the tracking down of evil criminals hiding out in the woods near the house – he did the sniffing – or unearthing buried treasure in the garden. He did the digging, much to my father’s displeasure when the only things of any value we managed to uncover were the seed potatoes he’d put his back out planting. If there was trouble as a result of our adventures we’d simply escape to my bedroom and dig out an Enid Blyton for further inspiration.

We spent hours together strolling around the cemetery. It may seem strange that a young child should be fascinated by death, but I found it all quite touching. On days when it was too wet or cold to visit the graves I would read the notices in the Barnsley Chronicle and found the often trite poetic clichés utterly beautiful.

In the burial ground itself, which was a short stroll from our front door, there were long, carefully tended paths to walk along and then pause at the poor, simple headstones of those without much money and the grandiose mausoleums, almost like houses, that were the final resting place of the rich merchants and coalmine owners of the past.

We’d take a few sandwiches and a bottle of pop and sit by the elaborate gravestones of tiny children who’d died in the 1800s. There were Sarahs and Edwards, Pollys and Williams. In some families four or five babies had survived for only a few months and I would read the unbearably sad poems out loud to Taffy, ears cocked, ever attentive as the tears poured down my cheeks.

‘With angel’s wings she soared on high, To meet her saviour in the sky’ is the only one that sticks in my memory, apart from the scary one on a grown-up’s grave positioned near the great wrought-iron gates at the entrance and which I copied into my diary.

Remember well as you go by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now so shall you be.

Prepare yourself to follow me.

I never failed to read it as we passed the grave and never failed to be absolutely terrified by it. We would run home to the warmth and safety of my mother’s kitchen and her wasted words of advice.

‘Of course you’re not going to die. They didn’t have such good doctors in those days. And if it upsets you so much, don’t go there.’ But for most of our walks I was irresistibly drawn to what Dad always tried to make me laugh by calling ‘the dead centre of Barnsley’. Not funny. Not funny at all.

An alternative route was the lane opposite my grandmother’s house which led to a bridge over the railway line and then the river. We would pause on the bridge and wait for a train to pass, the steam puffing up and over us. I loved it and the promise of bigger and better places it offered. Taffy hated it and would cower at my feet until the roaring noise was well past. But he loved the river. He swam and rolled around in the muddy banks whilst I paddled in the shallow water, dipping a fishing net in among the weeds and bringing out tiddlers and sticklebacks.

I had a jam jar with string tied around the neck for ease of carrying and at the end of the afternoon we’d carry our prize home to my mother’s ‘Don’t bring that smelly jar in here, and keep that dog outside – he’s filthy.’ We both had to hover around by the back door, whatever the weather, until she found time to turn on the hosepipe and give him a shivering wash down. He leapt at the warm, dry towel I proffered – old and tattered and kept for the job – and revelled in a good rub down.

I learned a lot from Taffy. As I grew older and struggled with the inevitable anxieties and tensions of the teenage years, he became my confidant when I realised that secrets told to a dumb animal were much less likely to be passed on than if they were told to someone you’d thought you could trust as a friend.

I discovered that kindness, low-voiced firmness and bribery tend to achieve far more than shouting, screaming or smacking. He would do anything he was asked as long as there was a treat clutched in my hand. He taught me that having a sense of humour was the best way of dealing with any sadness or worry. A dog has an uncanny ability of turning a lonely moment into one where there’s a companion who never takes life too seriously for too long. Taffy had the trick, as Butch does now. A head cocked to the side, ears erect, eyes full of love and mischief – one could even say a cheeky grin. You can’t stay miserable when faced with such innocent enthusiasm.

Taffy even managed to make me laugh during one of the greatest moments of shame and humiliation in a now rather long lifetime. I must have been 10 or 11 and, even though by now he was at least five years old, he hadn’t grown out of his puppy habit of gobbling up anything he found on the floor, no matter how seemingly unappetising. We’d just left the house and were walking along the pavement on our way for a tour around the cemetery with Mum (I’d persuaded her it was an interesting place to visit) when he desperately needed the toilet.

The mystery of what had happened to the stocking my mother had said was missing from under her bed was revealed. The only way we managed to get the whole thing out was for me to step on it as it emerged and my mother to walk him away from me. Passers by looked on in open-mouthed astonishment as my mother and I giggled, red-faced, and tried to explain we were not indulging in a perverse form of doggy torture. Taffy looked round at me with a look of grateful and slightly shameful thanks. I was helpless with laughter.

I also found that even the most devoted and faithful companion needs a life of his own. It was probably genetic, given his father was something of a tramp, as, I suppose, was his mother, but there were times when he would nip out into the ‘dogproof ’ garden and simply disappear. He’d be gone for several nights on the tiles, much to my dismay, but would always return ragged and exhausted, no doubt leaving many other little ginger mongrels dotted around the town.

I was in my second year at university when I came home for Christmas to be greeted as usual by his cheery, wagging welcome. Throughout our lives together he had always seemed to know when I was due and had never been absent from his place by the door where he waited for me. When I came home from school he was there, following me as I dropped my satchel in the hall, ran upstairs to change and took him for his walk. After a trip out in the evening, he appeared to hear me get off the bus a five-minute walk away and would leave his place by the fire to be ready for the opening door, and now, even though I spent long weeks away, he still seemed to anticipate my arrival.

On this occasion – I was 20, he was nearing 16 – he sat on my lap watching television all evening and nipped into the garden for his late night wee before bed. I didn’t worry too much when he didn’t come in. I guessed he’d gone off to a party somewhere and would soon be back. I never saw him again. He hadn’t been too well and my father reckoned he was the kind of independent spirit who would have wanted to go off and die alone. I was inconsolable and vowed never to fall in love with a dog for a second time.

His death was the first bereavement I’d ever had to face and his sudden absence, so final, seemed unbearable. We had grown up together and shared so many adventures and so much quiet, cuddly pleasure. I couldn’t imagine it would ever be possible to fill the gap he left, and to do so, despite advice from all around that the best way to deal with the death of a pet was to get another one, it felt that to try and replace him would be a betrayal of all the devotion he’d given.

For ten whole years I remained faithful to his memory. I finished university and managed to wheedle my way into the career I longed for. It was not easy in the early 1970s for a young woman to get herself on to the broadcasting ladder at the BBC. They turned me down once after a disastrous interview when my mugged-up knowledge of the technical side of the business far outshone my familiarity with the current events of the day. Lesson learned: never go to an interview without having devoured every available newspaper that morning. I eventually managed to persuade the manager at BBC Radio Bristol that I had potential and started at the very bottom of the ladder as a copy-taker in the newsroom.

Much as I loved radio, he persuaded me that survival in such a volatile industry meant having a wide range of journalistic skills – he taught me how to do radio, encouraged me to write and then packed me off to television in Southampton, which is why I found myself working as a reporter and presenter on the regional news programme, South Today. I’d met a dashing young naval officer, David Forgham, bought my own house on the edge of the New Forest and he was in the process of moving in (he’s still here thirty years on) when the news editor announced he needed someone to cover the New Forest agricultural show. I drew the short straw. A dull day of watching farmers parade their prize cattle around the ring and plump little girls whipping their Thelwell ponies over the jumps.

I was perched on a shooting stick, bored and waiting for the cameraman to finish filming the ‘idyllic’ country scene. He was brilliant but laboriously slow so we called him, partly out of impatience and partly admiration, ‘Every Frame’s a Rembrandt’. I spotted a large, untidy woman, hair falling out of her carelessly pinned French pleat, striding purposefully across the field, heading for the dog show. Trotting elegantly by her side was the cutest thing I’d ever seen on four legs. It was small, grey, square-nosed, with floppy ears that flapped up and down as it ran and a short, docked tail that wagged incessantly. It bore a strong resemblance to the Tramp from Lady and the Tramp and I was intrigued. It was a breed I’d never seen before.

I chased after the woman and caught her, breathless, just before she got to the show ring. She explained that it was a miniature Schnauzer. She was in a hurry. She was due to show right now. Yes, she had a litter of pups. She lived in a caravan in a field in the lee of Salisbury Cathedral. I’d be welcome to go and have a look. She’d be easy to find.

I rushed home after work, brimming with excitement at the thought of bundling David into the car, driving to Salisbury and coming home with my new best friend in my lap. Happily for the continuation of our relationship, he expressed no objection whatever to the acquisition of a dog. I’m not sure we would have survived had he said he hated dogs and couldn’t envisage coping with the responsibility. It would not have boded well for his future reliability as a hands-on father.

* * *

There are, in my experience, two types of dog breeder. There are those who do it not for the love, but the money. The bitches and pups are kept in cages and have little or no human contact. Then there are those who live in utterly disorganised and far less than hygienic chaos, but their animals – no matter how many they have – are part of the family. They’re petted and cuddled and any small indiscretion in the toilet department is either ignored or dealt with swiftly and without fuss.

This breeder, Diana, was of the latter variety. They had owned a farm in the path of the as yet unbuilt M27 and had been compulsorily purchased in favour of the road. They had bought the land in Salisbury and were in the process of building their own house, brick by laborious brick. The caravan housed husband and wife, two strapping sons and several giant and numerous miniature Schnauzers. We were reluctant to take the proffered grubby seats and worried what we might catch from the cups of coffee which appeared immediately, but the puppies were bright, healthy, friendly and affectionate. The one I’d seen at the show appeared to recognise me. He leaped on to my lap, licked me profusely and promptly fell asleep. He was perfect. His colour was grey, known in the trade as pepper and salt, and a boy, which was what I wanted.

Another, a more unusual black colour and a bitch, jumped on to David. There was some discussion about which we would take. I won. We paid £200 – a colossal sum in those days, which meant no dinners out and probably no holiday abroad that year – and drove home with William, who seemed to suffer no separation anxiety from his mother or his siblings. He was William from the moment we saw him, named after the character in the Richmal Crompton books we’d both loved as children. Our dog was ‘Just William’ from the word go – cheeky, naughty and irrepressibly amusing.

David was clearly delighted with him, but couldn’t stop talking about ‘the little black one’ we’d rejected. The next morning we took William into the garden for his first lessons in house training – it was a Saturday, so we didn’t have to worry about going to work – and David kept on going on about her.

‘You know,’ he finally came up with the clincher, ‘it’s all very well keeping a dog when you both have to go to work, but it’s not really fair. It would be much better if we had two dogs and then they’d keep each other company when we were out.’

We rang Diana immediately, found another £200 we didn’t really have and went off to Salisbury to collect her. She, it turned out, had already been named as Diana had half intended to keep her for breeding. She was known in the family as Hairy Mary. So, William and Mary. Names that went so well together. It seemed to bode well.

And so, for the next eighteen years, William and Mary were the best companions anyone could wish for. They took the arrival of two boisterous boys in their stride and were as playful and as gentle as any dog could be. William’s only fault was a tendency to be the canine equivalent of Houdini, able to escape from any confinement and take himself on a date. I recommended castration, as advised by our vet. David would hear nothing of it. He had no objection to Mary being spayed to avoid any unwanted inbreeding, but the thought of emasculating William was beyond the pale.

Quite how he survived the move from Hampshire to Clapham is a mystery to me. We were super careful about keeping him in as we lived dangerously close to the South Circular. Nevertheless, there would frequently be phone calls from the other side of Clapham Common asking us to pick up our dog, usually after I’d opened the door a mere crack to pass a cheque out to the milkman or the paper boy and William had managed to squeeze through a gap that wouldn’t have accommodated a mouse. We did, though, discover from a neighbour that he had a surprising degree of road sense. He was spotted trotting along our road to the zebra crossing, waiting on the pavement for a gap in the traffic and then scurrying hell for leather across the Common. He should never have lived for so long, but he did.

Just as I had grown up with Taffy, my two sons, Edward and Charlie, enjoyed the fun of the long walks a dog forces upon your daily routine and the comfort of a live and loving cuddly toy. The boys learned to care for an animal and treat it with respect, as I had. On Ed’s first trip to the vet for annual booster jabs – he was two – he left the surgery announcing that was what he would do when he grew up – become a dog doctor. He’s now 27 and a qualified vet.

The dogs were endlessly tolerant with the rough and tumble created by two small boys. Mary was patience personified – never minding when the ball sailed over her head to be caught by a giggling boy on the other side of the garden during a game of piggy in the middle with a dog as the piggy, chasing a football out on the Common like a mini Maradona and resigning herself to any tickling or ear tugging a toddler might choose to inflict. William’s policy was to teach an over-enthusiastic tease a little lesson. He would growl and grab a flailing arm, crossly, in his mouth. The boy would squeal, I would rush to the child in fear of a bite and find not so much as the tiniest tooth mark in the delicate skin.

We were a family of six and the dogs went with us everywhere. We rarely went abroad for holidays as we hated leaving them, even with a house sitter. Our best vacation ever was a tour around the Dingle Peninsula in Ireland in a horse-drawn caravan. No space at all in the caravan, so boys and dogs were deliriously happy at being able to share their beds – William and Mary were usually confined to the kitchen at night – and tons of space outdoors on exquisite, long, isolated, empty, golden beaches. The four of them would chase each other in and out of the sea, barking and squealing with absolute delight at the freedom they were able to enjoy.

It was Mary who began to deteriorate first. We had moved to the Peak District when Ed was 11, Charlie 7 and the dogs already in their teens. David and I were two Northerners born and bred, drawn home and wanting to give our sons the benefit of a similar Northern Grammar School education to the one to which we had access.

For William and Mary it meant a few traffic-free years of nothing but garden and fields and the occasional run after a rabbit. Eventually, at the grand old age of 18, Mary became so ill and incontinent, we took her to the vet who said senility was simply shutting everything down and it would be better to put her out of her misery. We held her close whilst the lethal injection was administered – the boys, bravely trying to conceal how heartbroken they were by sitting in the waiting room rather than watching the ghastly final act – and eventually David and I wrapped her in her blanket and we carried her lifeless body home and dug a grave at the bottom of the garden.

We laid her to rest with due ceremony. The four of us stood at her graveside, crying and laughing at happy memories of her skills as a footballer, insatiable appetite for anything sweet that might fall at her feet and love of rolling in anything unspeakably smelly she could find. William stood at my side, erect, like an old soldier, paying his own solemn and silent tribute.

William was a picture of utter misery without his lifelong companion. On the following Sunday night I had to leave home to travel to work in London, my weekly commute, knowing he might not be there when I got back. On the Wednesday, David called to say William’s breathing was laboured. Should he take him to the vet? I begged him to hang on if at all possible until I got home the next day.

When I arrived my beloved little fella hauled himself out of his bed and dragged himself across the kitchen to greet me. It was obvious he was in some pain and distress. We wrapped him up in his bed and he sat on my knee in the car whilst David drove. The boys were at school. Now, if there was one thing William hated above all others, it was the vet. He detested his annual jabs and it was the only time he ever made a fuss about anything.

As we turned the corner into the road where the surgery is situated, he pulled himself up with great difficulty, licked my face and died in my arms. I have no doubt he knew where he was heading and was determined he was not going to depart this life ignominiously with a needle stuck into his vein. We turned around and sobbed all the way home.

By the time we arrived and built up enough strength and courage to go down to the bottom of the garden and dig a grave alongside Mary’s, it was dark and raining. Tears poured down our cheeks as, wet and bedraggled, we laid him down. A car passed, flashing its headlights on to us. We caught the look of alarm in the driver’s face. We looked at each other. Only that week the crimes of Fred and Rose West had been uncovered, and here we were, digging a grave and burying a body at the dead of night. The situation was so macabre, we couldn’t help laughing. From beginning to end, William had given us nothing but constant amusement. How we would miss him. We vowed there would be no more dogs. The sense of loss was too great.