Читать книгу My Boy Butch: The heart-warming true story of a little dog who made life worth living again - Jenni Murray - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Honey, I Want a Chihuahua

Time does heal the sadness, and those resolutions never to feel this bereft again fade and are almost forgotten in the chaos that is middle-aged life with a job to do, late teenagers to guide, nurture and ferry about and elderly parents to support and care for. I had hardly thought about getting another dog as every waking moment was filled with responsibility.

The boys were stuck in a house in a remote part of the countryside which had been perfect for adventurous youngsters, but less appealing when school friends were spread over a wide area of Cheshire and sleepovers and parties became an essential part of their social life. David and I became unpaid taxi drivers and sources of help and information on subjects as widespread as Shakespeare, Buddhism and quantum physics. Our brains were permanently in over-drive whilst, at the same time, dealing with the mundane everyday – shopping, cooking, making sure their shoes still fit.

As they reached 17 and passed their driving tests we looked forward to a little more free time. It was not to be. My parents became increasingly needy of support as my mother’s Parkinson’s worsened, and one day out of every weekend was taken up with the hour and a half drive to Barnsley and back to offer whatever care and cheer we could. By the time the end came for them and I had to face the loss of my parental rock – a gaping emotional hole that still, four years on, I find difficult to rationalise – I was forced to deal with my diagnosis of breast cancer.

People often ask me how I coped with it all, and the only answer is that you just do. Up to that point I had led something of a charmed life – lovely family, great job and the rudest of health, but always, in the back of my mind, there had been a sense that somehow, some day, this presumptuous little working-class lass from Barnsley would be caught out. Life had no right to be this good. I can’t say I was surprised when all hell appeared to break loose at once. Both David and I were permanently overwhelmed and exhausted, falling into bed at night with barely a word exchanged between us and waking the next morning, dreading whatever new trial fate might dish out.

Slowly, but surely, the pressures eased. The grief was less acute as the months passed by. The children did well in their exams and were all but up and off to university, work and travel. The chemotherapy ended, my hair grew back thicker and bouncier than ever and the brilliant doctors who treated me declared my prognosis good. I felt well, and some of the old energy reasserted itself. The empty nest was not the disastrous cavern I had feared.

I began to get used to (and secretly rather enjoy) it, when that Titanic pile of shoes cluttering up the hallway came to an end; when the strains of drum and bass no longer emanated from the bedrooms; when there wasn’t the constant need to be shrieking ‘Turn that music down, will you’; and we could finally choose not to cook tonight’s meal if we didn’t really feel like it. But we were in no way fulfilling the promise we made to each other to take advantage of our lack of responsibilities and get out more – maybe even embark on some travel ourselves. We were becoming middle aged and more than a little staid.

Perhaps it was a necessary period of regrouping after the chaos of the hectic years that we had now tried to put behind us. There is a point in middle age when you realise you are not invincible. You’ve watched your parents deteriorate and are only too well aware that you will be next. Some days we sat opposite each other at the kitchen table and wondered whether, without the children and their future to discuss every day, we would ever again find anything to say to each other that wasn’t depressing. What, we wondered, could replace the youth and energy they had brought to our lives? Of course, we were still occupied by phone calls, emails and the occasional visit, the requests for help and advice and sporadic donations from the bank of Mum and Dad, but it became increasingly apparent that an injection of something we were at a loss to define was necessary to re-invigorate us.

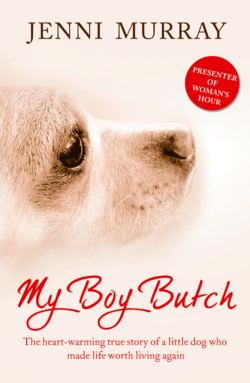

My thoughts, inevitably, turned towards canine companionship. Quite what put the idea of a Chihuahua into my head I’m not sure, as I’ve found myself strongly disapproving of the Chi celebrity culture that seems to have gripped Hollywood. I doubt there’s ever been a dog that’s enjoyed so much publicity since Lassie popularised the collie in Lassie Come Home.

The Taco Bell talking Chihuahua took America by storm, advertising Mexican Fast Food. Reese Witherspoon carried Bruiser – dressed in pink – in her designer handbags in Legally Blonde. In 2008 Beverley Hills Chihuahua was a hot success at the box office. Paris Hilton was rarely seen without Tinker-bell or Bambi. Madonna had Chiquita, Britney Spears sported Lucky and the movie hard man, Mickey Rourke, is said to own seven of the breed.

It’s Rourke with whom I feel most sympathy. A reporter from the London Times described arriving at his small house in New York to be greeted by ‘seven dogs, yipping, yapping and woofing and gleefully tripping over each other’. Rourke talks of the company his animals provide in what seems to have been a lonely and difficult life and his sense of responsibility even towards Jaws – a mean-spirited dog he took home from a rescue centre after it bit him on the lip. It had, he said, been ill treated by its previous owner. And he was clearly broken-hearted when his first dog, Loki, died at the age of 18 just before he was due to appear at the Oscar ceremony after his nomination as best actor.

Rourke says he chooses such small dogs because they tend to live longer and he becomes very attached. There is nothing of the designer doggie in its Gucci bag about him that’s become such a feature of the Paris Hilton school of ownership that’s had such a profound influence on the popularity of the breed.

The purchase of Chihuahuas in recent years has rocketed, despite the ever-escalating cost. You can expect to pay anything from £500 to £2,500, depending on the quality of the animal’s pedigree – the average price seems to be around £1,000. But the British Chihuahua Club’s Rescue Association reports more small dogs in need of rehoming than ever before. The internet small ads sites are full of notices for ‘my cute little Chihuahua … 1 year old … genuine reason for sale’. In other words – ‘Oops … this is a real dog. It’s not a toy. It makes messes in the house and I couldn’t be bothered to train it properly.’ Small dogs are notoriously difficult to housetrain in the early days without constant supervision.

Alternatively you can read into the advert, ‘Oops, it snapped at my two-year-old’ … Chihuahuas are too small themselves to withstand the sometimes casual cruelty of a small child. Or, of course, it could simply be ‘Oops, oh dear, he grew too big to fit in my handbag.’ Britney is reported to have got rid of Lucky after he snapped at her then partner, Kevin.

Strangely, the more I read about the ‘problem’ Chihuahua the more intrigued I became. How could such a little animal be so fêted on the one hand and so demonised on the other? An article in the Guardian newspaper’s G2 section headlined ‘LA’s Chihuahua problem? Blame it on Paris’ reported that Chihuahuas are now replacing pit bulls as the breed most often left at Californian shelters, with one San Francisco home telling the LA Times that, at current growth, the shelter will be 50 per cent Chihuahuas within months. ‘Animal welfare workers are calling it the “Paris Hilton Syndrome” after the celebutante whose obsessive acquisition of handbag portable dogs has inexplicably encouraged their popularity among people who don’t actually house the mutts in chandelier-hung scale models of their Beverley Hills mansions.’*

For me, living an oddly itinerant lifestyle that involves my weekly commute from the home in the Peak District I call Wuthering Heights to Wuthering Depths, the slightly grim, somewhat Bohemian basement flat in London, a small dog is essential for ease of transportation. Nor have I ever really been fond of big, powerful dogs, and Rottweilers and Alsatians really rather scare me. My son Ed the vet (I always feel slightly ashamed when I say that; it’s like the old Jewish mother joke: she’s in the swimming pool watching her boy and shouts, ‘Help, help, my son, the doctor, is drowning!’) goes by the old Barbara Wood-house mantra – ‘there are no bad dogs, only bad owners’, but the only nasty experience I’ve ever had with a dog was during my childhood and the dog was an Alsatian.

Our local vicar, his wife and children lived in a huge, imposing Victorian vicarage, reminiscent of the scary house on the hill in Hitchcock’s Psycho, and he began by owning one Alsatian as protection against intruders which eventually, as seems to happen with real dog lovers, became two, then four and eventually they were the proud owners of six of the breed – all brought up around their children and seemingly well trained and with the most gentle and accommodating temperaments.

I became involved with the family as a result of my loosely Church of England mother – she never went to church herself, but seemed to think it essential for my moral development. She insisted I go to Sunday school and be confirmed. I doubt she ever predicted I would be drawn to a short period of religious mania – I adored the drama of the High Church services and revelled in the bells, smells, music, intoned poetry of the services and the delicious cadences of the King James Version of the Bible – but she was patently delighted that I began to ally myself as a friend with the vicar’s children rather than with the somewhat scruffy, ‘common’ (her word, not mine) oiks who raced around our street, spoke in broad Yorkshire accents and had little ambition apart from the kitchen or the pit.

The dogs would always be around the large garden as we played and were rarely averse to being dressed in old hats and cardigans or put into prams and pushed around. But one day, as we all appeared to be playing merrily, the two older males began their own scrap for no reason we could deduce. The girl in the family – Jane – my closest friend, a pretty child with translucent skin, turned-up nose and a much envied golden ponytail, decided the best policy was to intervene and separate the animals in case they hurt each other. The underdog immediately slunk away as she leapt between them, shouting, ‘Stop it, stop it now!’ The bigger and stronger of the two growled, jumped towards her, put its paws on her shoulders and tore into her lovely face.

It immediately seemed to realise it had made a terrible mistake, turned and ran away. The rest of us looked on in paralysed horror as Jane screamed in pain. Her parents ran out to see what had happened, bundled her into the car and drove off to the hospital. The plastic surgeons did their best, but there was always an angry scar at the side of Jane’s face, and the dog was put down. It was a salutary lesson in animal behaviour – the two should have been left to get on with their scrap – and I’m not sure I would ever entirely trust a dog with the size and power to create such havoc. Even now I shiver slightly if I see one approaching in the park.

Soon after, I stopped going there – I found it hard to cope with Jane’s misery at the damage to her face and never again felt quite comfortable with the remaining animals. Eventually, they left the area and I lost touch with them completely.

So, a small dog it had to be. Friends with whom I shared my longing met my wittering about a really little dog being just the ticket with universal astonishment. They even went so far as to say they didn’t see me as someone who would be so shallow as to mince about with a designer dog or ally myself with what they saw as nothing more than a yappy, irritating rat on a string.

Nevertheless I found myself drawn irresistibly to the ‘Chihuahuas for Sale’ personal ads every time I sat down at the computer and read everything I could lay my hands on about the nature of the breed. The more I read, the more convinced I became that this was the perfect companion for someone in middle age who was not as fit as she once had been. Easy to manage physically, maniacally devoted to their owner, too small to be around very little children, not too expensive to feed, generally enjoying robust health and happy to go on a long walk if that took your fancy or a slow stroll around the sitting room if you didn’t feel up to a morning of violent exercise.

There was only one problem. David was absolutely adamant that he did not want another dog. During our first few years together, when the Royal Navy owned his time and could send him on a tour of duty at a moment’s notice, it was I who took on the responsibility of looking after William and Mary and arranging childcare for Ed when he was a baby. It was David’s longing to be a hands-on father who didn’t have to be away for months on end that drove him to leave the service and, eventually, when trustworthy and affordable childcare became increasingly difficult to find, he decided to take on the children whilst I became the breadwinner. He’d had years where full-time care was his job. He now relished the freedom to go out if he wanted to without worrying about anyone else’s needs. And that obviously meant, no dog.

In our relationship of thirty years’ standing there has rarely been a major disagreement. We concurred on where to live, what kind of house we wanted, how to educate and discipline the boys, but this was becoming a serious problem. I didn’t want to bring a living creature into the house if he would not be able to welcome it, but I was almost tempted to think I’d prefer the dog to him! Dogs don’t do grumpy!

There’s a theory, set out in The Female Brain by an American psychologist, Louann Brizendine, that a post-menopausal woman loses her nurturing gene. She’s said to become selfish in a way she has never been before and no longer feels it necessary to shop, cook, clean and care for those around her. Her children are generally up and off and her husband or partner can stand on his own two feet.

I can testify that it is to some extent true in relation to children and partners. I did get to a point where I was only prepared to cook and wash clothes or dishes strictly on a rota basis, but somewhere, deep in my soul, was the need to have someone or something small, helpless and needy to look after.

And I was not alone. We went out to dinner one evening with Gaynor and Ernie, friends of our age who don’t have children together. It’s their second marriage and Ernie’s boys are grown up; Gaynor hasn’t had a child of her own. The conversation came round to filling one’s time as one approached late middle age. The guys were all for working less hard, finding their way around the golf course, being free, at the drop of a hat, to see the world. Gaynor and I could talk of nothing but a dog and possible arrangements for reliable and affordable dog care, should the need arise. The nurture gene was only too present in both of us. Unsurprising, I guess, as psychologists describe the need to nurture as an essential part of the human condition, giving the lie to what was obviously nonsense about the gene diminishing as a woman gets older. I felt it as keenly in my mid fifties as I had heard the ticking of my biological clock in my early thirties.

I begged for a puppy for Christmas. I know, I’m not so stupid as to think a puppy should ever be bought for Christmas – it’s after the festivities that so many end up in shelters, unwanted and unloved, when a family that has bought in haste begins to realise how much of a commitment a dog is. But I really thought they would see how much I seemed to need a dog and would give in and surprise me.

They seemed to find it amusing to watch me unwrap a robot puppy which walked around the floor, barked, whined, sat on command and was about as cuddly and comforting as a lump of cold steel. I didn’t let them see me shed tears of disappointment. I did that in my bedroom, alone, and when the children were gone, after the holiday, I threw the stupid toy in the bin. And the house sank back into that cold, lifeless emptiness I found so dispiriting.

All alone, I read about dogs and was delighted to spend an hour with a marvellous Horizon programme on BBC television called ‘The Secret Life of Dogs’. It began to explain some of the reasons why I might be feeling so bereft and so full of longing. Researchers have found that we respond to the face of a dog in much the same warm way as we respond to small babies. Experiments placed human beings into a brain scanner and found that the same area of the brain lights up when shown a picture of a human baby as is illuminated when a dog’s face is shown. It doesn’t happen if the picture is of an adult human. And indeed there are noteworthy similarities in the faces of babies and dogs – a high forehead, sweet little button nose and big, innocent eyes.

Most remarkably, researchers trying to understand why the dog has become man’s (or woman’s) best friend have learned how the dog was domesticated by conducting experiments with wolves and, separately, with silver foxes. First they tried to raise wolf cubs in a domestic environment in exactly the same way as tiny puppies. The wolves showed absolutely no inclination to behave in an acceptable manner. If the fridge door opened they simply dived in and took whatever they wanted, regardless of being told ‘No’. They remained wild and independent. As one of the researchers who had cuddled, slept with and nurtured a wolf cub said rather ruefully as hers jumped up and took her meal from the table, tearing down the tablecloth and everything on it in the process, ‘He just doesn’t care.’ Eventually the wolves in the experiment were returned to the sanctuary to be with their own kind as it was thought to be too dangerous to keep them at home. Conclusion? They couldn’t be domesticated without a careful breeding programme.

My son Ed had close experience of this phenomenon when, during his year between school and university, he spent time at a wolf sanctuary in the mountains of Colorado. It was set up to rescue wolves who had mistakenly been bought as pets and had created havoc as they became fully grown. The most alarming animals he came across – indeed the only ones he felt presented any real danger to the people who cared for them – were the ones where, foolishly, an Alsatian had been crossed with a wolf. A wolf, he says, will never attack a human being unless it feels threatened. It will simply slink off in fear and seek its prey among sheep or cattle. A wolf dog is dangerous. It has the wolf ’s wild nature and the dog’s total lack of fear of the human being.

Yet all dogs, I learned from the programme, owe their genetic inheritance to the wolf. The process of domestication has been researched in Russia at a university in Siberia in Novosibirsk. There, over a 50-year period, silver foxes, a naturally wild and potentially aggressive animal, have been bred based on their temperament. Only the least aggressive have been allowed to breed and, during the 50 years, the researchers have found each new generation becoming progressively more tame and changing their physical characteristics. Sometimes the colour has altered. In some cases the tail has become curly. They are, it seems, becoming dogs, and the conclusion is that a similar selective process was used to change the appearance and the temperament of the wolf.

The most incredible experiments involved a complex bit of recording equipment which shows the scientists which way we look at faces. For some reason we humans don’t look straight at each other. We always look to our left when gazing at another person’s face, which means we’re looking at the right side of our subject. It apparently makes us easier to read. And, amazingly, the dog is the only animal to do exactly the same thing. It so wants to please us it has learned how to read our facial expression, our tone of voice, our vocabulary (most dogs at least know ‘sit’, ‘bed’, ‘ball’, ‘fetch’ or ‘walkies’) and one dog in the programme understood 300 words. Again, uniquely among animals, the dog can even follow our gestures, something not even our closest relative, the chimpanzee, can do.

When a chimp was offered treats hidden under cups it ignored the researcher’s finger pointing towards the one that contained the morsel of food and simply went its own way. Dogs, even the youngest eight-week-old puppies, followed the finger and succeeded every time.

It’s also been found that close physical contact with a dog produces the hormone oxytocin in both the owner and the dog. It’s the same hormone that’s produced when a woman gives birth and breastfeeds her baby. The French obstetrician, Michel Odent, calls it ‘the love hormone’. It’s been found to produce feelings of contentment and relaxation.

It doesn’t surprise me to discover that people who have a close and affectionate relationship with a dog suffer less stress, are less likely to suffer a heart attack and, if they do, are more likely to recover. I’m not sure whether that’s a result of the calming effect of the oxytocin and the frequent cuddles you get with a creature that offers and receives unconditional love or whether it’s the fact that dog owners get out more because they have to be involved in more physical exercise than the non-dog owner who doesn’t have to do ‘walkies’ three times a day, but the evidence is compelling. And it must be noted that during my years of dog ownership I never ailed a thing.

So, my arguments in favour of having another dog were bolstered by the science. There were other slightly alarming nuggets of information in the programme which I thought it might be profitable not to share with the partner I call, in less affectionate moments, ‘him indoors’. There are 8 million dogs in the UK alone, which is an awful lot of unwanted waste matter on pavements and in parks.

I have always held to being a responsible owner and never leave anything behind, remembering ghastly times when the children were young and we lived in London near Clapham Common. They would run, somersault, play football and cycle and inevitably bring home something unpleasant on their shoes or trousers. Horrid. The other truly scary statistic informs me the average dog owner invests £20,000 in their animal over its lifetime. That’s the initial cost of the dog, insurance, vets bills, food, toys, beds and other paraphernalia. It’s an amount I shall choose to ignore.

But all the stuff about the health-giving properties of dog ownership – now that was really useful. David had been the most attentive of carers during my nasty brush with those unwanted cancer cells. He stood by me manfully through discussions with the surgeon that no man should ever have to witness – a cold and matter-of-fact analysis of how best to remove a part of his partner’s body of which both he and she are particularly fond. He was at my bedside when I was taken to theatre and still there when my morphine-addled brain began to come round and talk nonsense.

He brought me home and tucked me up. He was there for the chemotherapy sessions and held the bucket by my bed when the nausea kicked in. He had, I knew, had quite enough of caring and would do anything to make me take better care of myself than had been my habit in the past.

I needed to develop a strategy. It involved appearing rather depressed and down in the mouth. It was not, after all I’d been through, entirely a performance, although I confess now to playing it up a bit. I became reluctant to go out much. I developed a passion for a lie-in in the morning, a bit of a nap in the afternoon and then an early night. He was clearly worried that I was not as well in the hours spent at home as I appeared to be when I was trotting off to London to go to work, or seemed when he heard me coming out of the radio. I was obviously, I think he realised, short of something to occupy my time.

Eventually, he asked me what he could do to help me feel better. Bingo! I shamelessly played the cancer card. I told him I hoped to live for many more years – an aspiration he seemed to share. Fifteen to twenty, at least. I discussed my oncologist’s assurance that, after the type of breast cancer I’d had and the subsequent treatment, my prognosis seemed to be good. A dog, with luck and good husbandry, would share most of those fifteen to twenty years, especially a Chihuahua, known for their longevity. A bright little dog would give me a reason to get up in the morning. It would force me to go out for walks and get the exercise I so desperately needed.