Читать книгу Lucca - Jens Christian Grondahl - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLea stood on the platform beside her large bag, shivering in the cold and looking down at the shining tracks. He thought she had grown although it was only a fortnight since they had been together. Monica had bought her some new clothes. She wore a thin jacket, white jeans, white socks and white trainers. She did not see him until he was almost in front of her, then she smiled with relief and hugged him, but he could feel her disappointment at his arriving late. He carried her bag through the vestibule, feeling ashamed at the excuse he had fabricated on the spot about a queue in the supermarket. Two down-and-outs stood near the exit drinking beer. Their washed-out denim jackets were spotted with rain, one of them had the usual dog on a lead. The owner of the dog raised his glass in a friendly toast to Robert as they passed. Lea wrinkled her nose, assailed by the reek of beer and wet fur. On the way to the car she told him a friend had invited her to stay with her parents in the country during the summer holidays. He turned in his seat as he reversed out of the parking place. Lea struggled with the safety belt before getting it out to click in place. She could come and stay with him during the holidays too, he said, changing gear. But Monica had plans for them to go to Lanzarote. Wasn’t it too hot there in the summer? We’ll hit on something, she said, smiling at him in the mirror. It was a very adult remark. It sounded like something Monica might say. Lea did not really resemble either of them, apart from having his hair colour, chestnut brown. She had been utterly herself from the start, a totally complete person who had merely used them as assistants in her advent. She asked him what was for dinner. Leg of lamb, he told her and asked after Monica and Jan. They used first names, had done so since their divorce. She was to give him their regards.

He had a meal with them sometimes when he was in town, it meant something to Lea. It was surprisingly easy, all three were very civilised, but he usually left after kissing Lea goodnight. Sometimes they referred to the divorce, but always in abstract terms and without mention of the little mishap that had brought about the change, when he arrived home too early one winter Sunday. Robert wondered occasionally whether he and Monica might still have been together if he had not caught her out. If he had just left a message on the answering machine when he called home from Oslo. Then his colleague might have had time to take himself off and everything would have seemed different. Perhaps she would have grown tired of her lover, tired of all the emotional turmoil, secrecy and practical lies. To exchange one doctor for another wasn’t exactly revolutionary, anyway.

They did not seem passionately in love, she and Jan, but of course that might just be tactfulness, to make it look as if their relationship was already as much a matter of routine as his and Monica’s marriage had become. They did not even refrain from kissing each other heartily when he was there, the way married people kiss, like siblings. Perhaps it was really some kind of sophisticated consideration, thought Robert, a blind to conceal their erotic hurricanes. Unless that was how you ended up in any case, like siblings, because in the end establishing a family was like returning to the family you thought you had left.

Lea sat on the sofa watching television while he unpacked the shopping in the kitchen. As usual he had bought too many things for lunch and too many biscuits, as if the larder had to overflow with abundance when Lea was coming. He could not find the leg of lamb. He went outside again and opened the boot, but there was nothing in it except the first aid box, the jack and the spanner for changing wheels. Andreas Bark must have taken the bag with the leg of lamb when they carried his things in. He could not face driving out to the house in the woods a second time that day, and he certainly could not face the other man’s drama again.

He had forgotten to close the gate in the garden fence. Behind the wide panorama window onto the terrace he saw Lea’s turned away figure and the television screen trembling like a drop of quicksilver, floating in the semi-darkness of the living room behind the grey hatching of the rain. She was watching Flipper. As a child he had also loved the plucky dolphin’s adventures, and now the series was being repeated it was his growing daughter sitting there dreaming of Florida’s blue lagoons. It had become a classic. What a cultural inheritance! He had cautiously tried to introduce her to such varied offerings as Vivaldi’s Seasons and Debussy’s Children’s Corner, but they could not compete with the Spice Girls and Michael Jackson.

He stood there in the rain for a few moments reminiscing over the graceful dolphin and the sun-tanned, well-organised family it had rescued from so many criminal plots against their sun-warmed happiness. The bright technicolour of the films had faded with the years, and the whole thing seemed pretty naïve, but he clearly remembered how he had meditated over the wise playful dolphin Saturday after Saturday. Its feats of grace when it reared and turned somersaults over the coral-blue water expressed pure unsullied joy. Neither more nor less exhilarating and jubilant than Vivaldi’s trilling, violin-shimmering springtime.

He cooked the burgers they were to have had the next day. They would have to go and get a pizza when that time came. Lea was still watching television. He would really have liked to have her help in the kitchen. She did that sometimes, it was a pleasant way of spending time together, but there was something about her motionless and almost melancholy concentration that made him leave her alone. Perhaps she was tired.

She did not have much to say over dinner. If it stayed fine, he said, they could make a start on the kitchen garden, and he reeled off the list of seeds he had bought, but she didn’t seem particularly keen on going out to dig. Last time she had been enthusiastic, it had actually been her idea. He asked her about school and what she had been doing since last time and she responded, slightly dutifully, he felt, but she did not volunteer anything herself. She had begun to go riding and almost made a little story out of her account of how a young horse had thrown off one of her friends, but the girl had not been hurt, and since then her horse had behaved perfectly. She ate nicely, that was something Monica considered important. Yes, she loved the roller skates, they were ace.

He couldn’t help smiling at the word. It was like seeing her in nylon stockings for the first time when six months ago she had played the princess in the school play, with mascara on her eyes, dark red lips and a beauty spot on her cheek, when he didn’t quite know what to think. And the trip to Lanzarote? Monica had said something about the beginning of July and when she came home, there was her friend with the summer cottage. He did not want to dig away at the subject too much, but he felt a stab of sadness at the prospect of not seeing her during the holidays. Or was it just as much the thought that Monica and Jan would have a monopoly on her? He asked if she would like some dessert, he had bought ice-cream and made a fruit salad. She chose the fruit salad. He wondered whether it was out of politeness, because he had taken the trouble.

She seemed sad, but perhaps he was merely over-interpreting her recurring silence and withdrawn expression. He was always afraid of being inattentive. After a while, as she sat pushing the last slice of banana around her plate with her spoon, he asked if anything was worrying her. She avoided his eye. No, nothing. He gently stroked the back of her hand with his index finger. Anything at school? At home?

She left his hand there, stroking cautiously. She looked away, into the twilight of the garden. Then she said it had stopped raining. She was right, the swishing of the rain had ceased and the evening sky brightened behind the silhouetted birches, a soft yellow under the hurrying frayed blue clouds. She helped him clear away and fill the dishwasher. He asked if she would like a game of table tennis. She looked at him for a moment. Okay, she said, smiling, and the smile seemed genuine. They played for twenty minutes, she was tough, he started sweating, out of breath. It was silly to play straight after dinner, but she seemed to enjoy it and he liked to watch her quick, lithe movements.

Afterwards he made himself some coffee. They sat down to watch television. She leaned against him on the sofa as usual, covered with the rug. Neither said anything much, again her gaze was distant and abstracted. Now and then he raised some subject or other in an attempt to get a proper conversation going, but she just responded with brief comments as if to get it over with, apparently absorbed in what was happening on the screen. After she had gone to bed he poured himself a whisky and listened to one of Bach’s cello suites in an old recording by Pablo Casals. He regretted being so direct in his questions over dinner. The old music wove its logical web around him and he followed every one of the crisp trembling threads in anticipation of their nodal point until he felt he was the spider.

When he went into the bathroom in the morning she had carefully hung her wet bath towel to dry on the bar above the heater. She was nowhere to be seen. She had made her bed as neatly as a housemaid would do. When they lived together she had always left towels crumpled up in a corner of the tiled floor, and her room looked as if it had suffered an earthquake, but of course she was older now. She was out in the garden with her fingers dug into the front pockets of her tight jeans, her face lifted to the trees. He couldn’t see what she had caught sight of. A bird, maybe, or a cloud. He went into the kitchen to make coffee. When she came in by the scullery door soon afterwards she wiped her feet on the door mat as thoroughly as a guest.

It had cleared up during the night, the sun was drying the grass, and if not for the wind, it would almost have been warm. She spent the morning in the kitchen at her homework. He asked if there was anything he could help with. She looked up and smiled, there was nothing. After breakfast he took the new tools and the basket of seeds out to the small corner of the garden he had pegged off in a rectangle. To begin with she sat beside him watching him dig, absently plucking small handfuls of grass and dropping them again. He grew red in the face from slaving away bent over, and began to feel foolish. He certainly wasn’t a gardener.

Then she got bored with just sitting there and soon she was digging beside him until the sweat trickled down her forehead. She enjoyed it and made a mock grimace of disgust when she cut a worm in half and saw the two pink pieces wriggle off in different directions. He found an animal’s skull, and they squatted down with their heads together as he brushed earth from the domed periosteum. They could not agree on the kind of animal it belonged to. A weasel, she said. He thought it might be a badger. She gave his shoulder a friendly shove. How stupid he was! He carried the skull carefully indoors on his outstretched palm, and they found a little box which she filled with cotton wool, so she could take it to school. And get the matter settled, as she said with a pedantic air which made him smile.

When they went into the garden again they found Andreas and Lauritz on the lawn. Andreas held out a supermarket bag and smiled apologetically, either because he had called unannounced or because he had taken Robert’s leg of lamb. He had looked up the address in the directory, he explained, as if to account for his unexpected appearance. Lea looked expectantly from one to the other, Lauritz hid behind his father’s legs.

Robert felt obliged to show some hospitality. He suggested a beer. Andreas didn’t need a glass, thanks. The children had orange juice. They sat in the sun on the terrace, conversation hung fire. When Andreas leaned his head back to drink from the bottle Robert imagined he was taking in the whole property and the surrounding hedges and fence dividing it from the other houses and gardens. He who lived a free life in the woods, in his leather jacket, riding a rusty lady’s bicycle, dramatist and pioneer in one and the same person. It must be good to live in a house like this, where everything worked. Yes, it was actually. Robert picked up the signal behind the smooth reply. The other man persisted. Did it have a sauna as well? No, replied Robert, looking down at his tennis shirt with the crocodile. There was in fact neither sauna nor jacuzzi, and he didn’t have a parabolic reflector, either. Lea giggled and Andreas smiled fatuously. Robert loved her for that giggle.

Lea took the boy’s hand to show him round the garden, and he went along with her trustfully. She seemed very grown-up as she entertained the child and encouraged him to work the newly dug soil with a hoe, taking care he did not hurt himself. She talked to the boy in a cheerful friendly voice, kneeled beside him to be at eye level, watching him and sometimes smiling as he made faces and clumsy movements. She had pulled her hair off her face and tied it in a pony tail. Now and again she brushed aside a lock from her cheek and pushed it behind her ear with a feminine gesture.

What a pretty daughter he had. Yes, said Robert. Andreas picked at the label of his beer bottle. Robert must excuse him for being a nuisance the day before, but he had no-one to talk to, not here, and it was all . . . he sighed. Robert waited. Lea made the boy chuckle down at the end of the garden. The whole thing was such a mess . . . how could he put it? That was what he had been about to tell Robert yesterday, when Robert had to go. The night Lucca crashed he had told her he wanted a divorce.

The shadows were lengthening. Lauritz came running over the grass. Andreas rose to his feet, lifted him up and swung him round in the air, as Robert had seen Lucca doing in the photograph in their kitchen. Lea went over to him and put a hand on his shoulder. How about asking them to stay for dinner? She smiled at him, her head on one side, as if she were his little wife. It would be nice, wouldn’t it? She would help with the cooking. They could go on with the digging tomorrow. Andreas sounded surprised at Robert’s suggestion. Now they had cycled all this way! But they didn’t have to urge him, and he insisted on taking over the cooking. Inside he looked around at the design furniture and the prints on the walls and said admiringly what a lovely house it was. It was very Scandinavian and timeless, and the projectile-shaped Italian furniture in the farm labourer’s house in the woods crossed Robert’s mind. In the other’s eyes he was obviously a true suburbanite.

Andreas turned out to be a practised cook, and he set Lea to preparing the vegetables while he stuffed the joint with garlic. There was nothing left for Robert to do, and suddenly the kitchen, where he usually ate alone, seemed small. Lauritz sat at the table drawing round-faced moon-men with shaven heads and matchstick bodies and he walked to and fro, poured out red wine, put some olives in a bowl to nibble and played extracts from Italian operas for them. Andreas sang along to several of the arias from Cavalleria Rusticana, wrinkling his eyebrows and shooting lightning glances that made Lea double up with laughter. Robert had to admit to himself it made him jealous, in the midst of his astonishment over Andreas’s familiarity with Italian bel canto. With his untrimmed bristly hair, black T-shirt and unshaven charm he looked more like a bebop fan. Robert felt he had been invaded, but most of all he wondered at the easy, almost light-hearted atmosphere his guest had suddenly generated so soon after he had come out with his guilty revelation.

In the midst of it all the telephone rang. It was Jacob. Robert asked him to hold on and went into the living room, turned down the music and picked up the receiver. He could hear them chatting in the kitchen and called out to Lea to put the phone down. Had he got visitors? Robert said some friends had called. It sounded authentic, he thought, yet awkward, somehow defensive. He hardly ever had guests. Jacob was disappointed, he could hear. He was going to ask them over. It was about time he introduced them to his daughter. Robert said it would have to be another time, and felt pleased Andreas and Lauritz had turned up. Jacob asked if he would like to play tennis on Monday. There was something he wanted to talk to Robert about. What? Jacob lowered his voice, he would rather not mention it on the phone. Robert said Monday would be fine.

They laid dinner on the pingpong table, it was Andreas’s idea. There wasn’t enough room at the small kitchen one. They sat around one half of the table and while Lauritz dropped the contents of his plate into his lap with methodical concentration, Lea asked his father how you could become an actor. Obviously the role of princess in the school play had put ideas into her head. Andreas answered her naïve questions patiently and she listened with a grown-up smile and a hand under her chin, holding the stem of her wine glass of coke. After dinner she tried to teach Lauritz to play table tennis. She stood him on a chair and didn’t give up until to his own surprise he managed to serve.

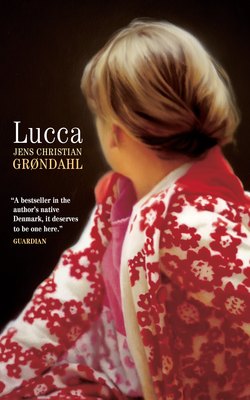

Lauritz fell asleep on the sofa. Lea served coffee like a real housewife. It was too weak, but Robert didn’t mention that. She listened while Andreas talked about Italy. He and Lucca had lived in Rome before Lauritz was born. He spoke of her as if nothing had happened. As if she hadn’t practically driven herself into death one night the previous week because he had told her he wanted a divorce. They had had a little flat in Trastevere, and Lea swallowed his anecdotes about the quaint inhabitants of the working-class district who shuffled out shopping in slippers and dressing gown, about the winding alleyways with peeling walls and washing lines, about the baker’s wife with her moustache and the blacksmith’s chickens. Yes, chickens . . . imagine, in the middle of Rome! Robert thought it all sounded rather too authentic. Lea said Lucca was an odd name. Andreas explained that really Lucca was a boy’s name. Her parents had been sure she would be a boy. But they had hung onto the name. Her father was Italian, she was named after the town in Tuscany where he was born. Lea thought it sounded beautiful and looked at Robert.

She began to yawn and reluctantly gave way to sleepiness. She kissed Robert on the cheek when she said goodnight, hesitated a bit and then gave their guest a kiss too. For a while the two men sat in silence over their coffee cups and Calvados. The easiness had disappeared with Lea. They could hear her gargling as she cleaned her teeth and soon afterwards the sound of her door being quietly closed. Lauritz turned over in his sleep, Robert put the rug over him. Again he felt surprised at how his guest could change expression from one moment to the next. Andreas lit a cigarette and flopped onto the sofa, blowing out smoke. The corners of his mouth drooped, a lock of hair fell over one eye and he fixed his vacant gaze on a point on the carpet beneath the sofa table.

Obviously, he said, he felt guilty, but . . . he was not to know she would . . . it couldn’t have come as a complete surprise to her. Just after he’d said it he thought she had taken it with a strange composure. They were still at the table after dinner. Lauritz had been put to bed. To start with it seemed they would be able to talk sensibly about it. It wasn’t hard for Robert to visualise, he had sat in the same kitchen, at the same table, and now he knew what she looked like. She had asked if there was someone else. He sighed deeply. He had said no . . .

Might he have another Calvados? Robert made a gesture. Andreas poured for both of them. Up to now everything had been so banal, the marital scene one night in the house beside the woods and the unfaithful husband sitting here on his sofa marinating his guilt in Calvados. He was not in the least sorry for him, though the banality of the other man’s story made Robert despise him. He was just so tired suddenly. Andreas downed the contents of his glass in one gulp and looked at him through the billowing veil of smoke from his cigarette. He leaned his sorrowful face on one hand so his cheek half closed one eye and made him look like a grieving Caucasian. What sort of seductive silhouette was dancing behind his despondent gaze? Was she playing a tambourine?

He had attended the rehearsals of his play in Malmö. The set designer was ten years younger than him, from Stockholm, one of the new bright sparks. Much was expected of her. Andreas cast a glance out of the panorama window to the sheer deep-blue patch of sky over the dark outline of the treetops. He would never have believed it would happen to him again. He had thought he was too old to fall in love. He looked down at his empty glass. He had not slept with anyone else since meeting Lucca, although there had been plenty of chances. In his world . . . he smiled and looked at Robert again. Yes, people were always hopping into bed. But it was probably the same in hospital, too? Robert shrugged his shoulders and said nothing.

Ironically enough they had met each other in much the same way, he and Lucca. She was an actor. At the time she had been with a director, much older than herself. He had been to visit them at the director’s house in Spain. The old guy was going to put on a play of his, he was a big shot, it was an honour. And then suddenly she had been there, Lucca, and everything had become alarmingly complicated.

His eyes sought Robert’s. Everything had gone so fast, and in a flash she was pregnant. He lit a fresh cigarette and picked a fleck of tobacco from his tongue. When he had jumped into it he hadn’t dared to confront his doubts at first. Lucca just had to be the one, and so she was, at least for a time. As soon as they got to Rome they spoke of finding a house in the country. But how could he put it? It wasn’t just the routine, the inevitable jogging along when you had a child. It was something else, something deeper. A lack he could not explain and so had been able to ignore for long periods at a time.

He felt he could not share his innermost self with Lucca. She didn’t understand him, so she did not know how to bring out those depths in him he could hardly explain. He flung out his hand and almost upset the bottle. Robert threw a glance at the sleeping boy, covered by the blanket, the table tennis ball clutched in his small hand. Lucca had turned her back on the theatre after she had Lauritz, completely absorbed in the child and in building up their home with a trowel and great expectations. But what use was that, when she wasn’t . . . their mutual attraction had been mainly physical. Bed had always been good, as a woman she was very . . . well . . . he inhaled and blew out the smoke with a deep sigh. But there was something lacking.

That was when Malmö came into the picture. It wasn’t just a question of erotic fascination. Although she was very beautiful, he emphasised in passing. Her parents were Polish Jews, and she had that special blend of inky black hair, very white skin and ice-blue eyes. Robert couldn’t help smiling. Gypsy or Jewess, it came to the same thing, a tambourine would be almost superfluous. But there was something else that made a difference, something more . . . Andreas did not know how to describe what it was she did to him, the Jewish production designer. It was as if she touched on something inside him, deep inside. As if she made some string vibrate, a string he didn’t know he possessed. And each time he took the last hovercraft from Sweden he could feel his life’s centre of gravity had moved so that he left it behind when he travelled home to Copenhagen through the night.

He hadn’t even been to bed with her, in a way that was crazy, but it did convince him there was something different and more serious afoot. After the première she had gone back to Stockholm. He had called her on the quiet and they wrote to each other, he hadn’t written that sort of letter for years. Several weeks had gone by like that. He had been on the verge of collapse, surrounded by bags of cement and ploughed fields and Lucca’s anxious, searching eyes. Luckily he had planned a month’s stay in Paris to work. She must have noticed there was something wrong, but she did not question him, neither then nor when she went to stay with him for a few days. And finally he had made up his mind. He had just come back from Paris on the night he told her. He stopped talking and poured himself another Calvados, this time he forgot Robert. The production designer knew nothing about his decision. He leaned back his head and drank. He had wanted to make a clean sweep first, he said, wiping his mouth on the back of his hand. And now . . . now he didn’t know what to do.

Robert needed a pee. It wasn’t because he did not want to listen, he said, going out to the bathroom. After he had flushed the pan and washed his hands he stood at the basin sceptically observing his own reflection. Why had he allowed this strange man to invade him, ingratiate himself with his daughter and keep him up late while he drank him out of the house? What were Andreas Bark’s romantic chaos and pathetic attempts to justify himself to do with him? He felt like having a cold beer, but let it pass. If they started drinking beer he would never get rid of him.

When he went back to the living room Andreas had put on his leather jacket. He kneeled down in front of Lauritz, who sat sleepily with his bicycle helmet over his eyes as his father tried to get his feet into his shoes. Robert asked several times if he should drive them home. On no account! Besides, it was fine now, Andreas smiled, the moon would light their way. Robert grew quite alarmed at the idea and told him to ride carefully, almost fussing over them. They went outside. The moon was full. He stood looking at Andreas’s silhouette as he bent over his bicycle. The playwright wobbled slightly as he disappeared into the shadows under the trees, until only his rear light could be seen. After a few moments he reappeared, still smaller on the silvery grey asphalt between the blacked-out houses.