Читать книгу Liberty's Wounds - Jeremy Amick - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Trouble from the Beginning

“I hadn’t even been born and I was already in trouble.” – Bryce Lockwood, sharing a humorous account of his sister’s birthday celebration, which was followed by his unexpected birth in December 1939.

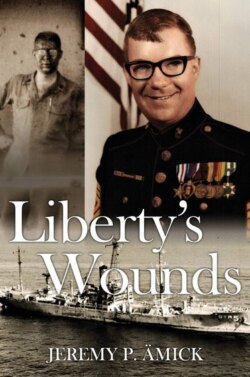

Trouble. If an individual were granted the minor indulgence of using a single noun to characterize several of the most formative experiences of Bryce Lockwood’s life, trouble certainly seems one of the most fitting. From the early difficulties he created for his sister and mother during a birthday celebration that began prior to his birth to the wounds he sustained while serving as a resilient U.S. Marine during the attack on the USS Liberty less than three decades later, his life’s narrative has been rife with a mixture of both interesting and challenging circumstances.

Before his birth on a small farm only a short distance from the rural community of Nineveh Junction, New York, his mother, the former Iva Dewey, made preparations for a modest birthday celebration in 1939 for her three-year-old daughter, Edith. But, as his mother soon discovered, attempting a birthday celebration while full-term with an unborn son would soon lead to a mirthful memory for both a mother and daughter, though it might not have been viewed in such a humorous light at the time it unfolded.

“It was December 19, 1939, and my sister Edith had been born three years earlier,” Lockwood stated in jovial reflection. “My mother had been planning a little birthday party for my sister even though there had been a sizeable snowstorm a little while earlier and the ground was covered with about eight inches of snow.” Pausing, he added, “My mother had baked a beautiful cake for my sister using the old wood stove in our house because we didn’t have any electricity for an electric oven at the time. When the cake was finished and decorated, she carried it outside. She had taken out one of the chairs from the house and plopped it in the snow so that she could set the cake on it for a birthday picture.”

His mother then stood Lockwood’s three-year-old sister next to the chair and snapped a photograph with her little Brownie camera to capture the image for posterity. Picking up the cake to carry it back to the warmth of the indoors, where it could then be enjoyed by her three-year-old daughter, she suffered a sharp labor pain, which resulted in her dropping the cake upside down in the snow where the family dog, Babe, had been sitting only moments earlier.1

With a laugh, Lockwood murmured, “I hadn’t even been born yet and I was already in trouble.”

During his birth on the family’s farm shortly thereafter, Lockwood’s mother was attended by a friend from college who had become a registered nurse. Despite the youngest Lockwood’s unanticipated and marginally problematic entry into the world, the event would soon become the basis for mirthful reflection since he now shared the same birthdate as his sister, separated by exactly three years. The youngest of his siblings, Lockwood noted that his mother gave birth to five children, including his older sister Edith and an older brother George, the latter of whom was born in 1930. However, there existed an undercurrent of sadness from his mother’s past because she had given birth to a daughter, Margaret Esther, who passed away from pertussis on January 4, 1936, just three days shy of turning two years old, and a son, Raymond Jr., had died from streptococcal infection on June 25, 1936, at only the tender age of seven.

“It was a very difficult time for my mother, not only because she lost two children within such a short period of time, but also because she had been pregnant with my sister Edith through most of this time of mourning,” he said.

His father, Raymond Lockwood Sr., was born in 1905 and by the time the United States entered World War I a little more than a decade later, he was not yet a teenager and much too young to be drafted into the military. When the Selective Service Act of 1940 was instituted in September 1941, Lockwood’s then thirty-five-year-old father would have been required to register for the draft. Even though the elder Lockwood was among fifty million citizens between the ages of eighteen and forty-five years old who were required to register for draft by the end of the war in 1945, he received a deferment from military service due to his age and the fact that he had three children and a wife to provide for.2 Instead, Lockwood’s father spent the years leading up to the war building a couple of poultry houses on the family’s small farm, raising pullets and selling eggs—work that helped provide a meager income during the difficult and economically stressful period of the Great Depression. The family, like most living in a rural environment during that era, did not have any disposable income to speak of and finances were often tight, necessitating that they make do with what little they could scrape together.

A grinning 10-month old Bryce Lockwood, seated on the cart, is pictured in October 1940 at their home near Nineveh Junction, New York. Also pictured are his older brother, George, and his older sister, Edith. Courtesy of Bryce Lockwood

“The community we lived near, Nineveh Junction, was decades ago a booming railroad town situated at the intersection of two branches of the Delaware and Hudson Railway. The crews would change out in the town and they often stayed across the street from the railroad yard in a place called the Central Hotel, which had quite the questionable reputation,” he grinned. “My great-grandfather owned a country store nearby called Arrowhead General Store—it was part of a chain of stores that no longer exist. It was one of those types of stores that you used to see in a lot of small towns, providing a range of services for the community with a restaurant and a post office inside.”

Around the corner from the rail yard was a brick building where boys from the area would find empty liquor bottles that the men working on the rail crews had discarded once they had been entirely drained of their contents. As a form of entertainment, Lockwood remembers several of the kids from the neighborhood grabbing bottles from the pile and slinging them against the brick wall, laughing as the sound of the shattering glass helped break the monotony of otherwise uneventful summer days. Though now decades past, Lockwood also recalls clearly the moments he spent ambling through his great-grandfather’s store as a young boy, gazing in fascination at the assortment of horse harnesses that hung in the rear section of the store.

“Things were much more basic then and the store had no electricity back in those days; all of the lighting was from oil lanterns,” he said. “I can also remember that my great uncle had been allowed to set up a glass case in the store that contained a collection of coins that he had for sale,” he added. “It may have been a small town, but I can certainly remember a beehive of activity going on in that store.”

When Lockwood was but a few years old, his father made the decision to pull up their rural stakes and moved the family into the community of Afton, New York, only a few miles down the road, where he could secure employment that would provide a more substantial and steady level of income.3

“My uncle offered my father a job with Crowley’s Milk in Afton sometime during World War II,” Lockwood recalled. “The company would take in raw milk from farmers in the region, cool it in large tanks and then ship it by truck into New York City, where it could be bottled and distributed to be sold at retail outlets throughout the region.” After a momentary pause, he added, “I can remember going down to the milk plant after school while my dad was working there and turning the taps on one of those large tanks to get some of the raw milk to drink.”

When Lockwood’s father was employed by Crowley’s Milk Company, Inc., the company was headquartered in Binghamton, New York but had receiving stations and plants in several communities to include Afton. The American dairy was established in 1904 and grew to manufacture and distribute a range of dairy products such as milk, cottage cheese, sour cream, and yogurt. The company was later purchased by HP Hood LLC in 2004, when the company celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary; it continues to do business as Crowley Foods.4

Prior to his parents’ marriage, his mother had been employed as a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in East Afton. One of scores of small educational buildings dotting the rural New York landscape in the years before the consolidation of the burgeoning school system, it was a simple structure where she delivered a basic education to students of varying ages. The schoolhouse, Lockwood explained, was spartan with no modern comforts such as electricity or running water.

After she married and became a mother, Iva Lockwood decided to remain at home and focus on caring for her family. In the 1950s, as the children began to get a little older and did not require her constant attention, she learned about an opportunity to remain at home while also making a little money by becoming a salesperson for the Stanley Home Products Company. Established in 1931, the company became one of the founders of direct selling, utilizing hostesses to plan parties in their local communities to sell a range of company products including brushes, cleaners and beauty aids to friends, family, neighbors, and associates.

“Mom really liked the idea of working for Stanley and she really became very good at it,” said Lockwood. “She had a way of connecting with people and had a whole bookshelf full of trophies that she had earned while she was selling products for the company.”

Coming of age in the small community of Afton, Lockwood remarked that he was “sick a lot through my grade school years, suffering from measles, mumps, chickenpox… you name it.” Despite his illnesses, he recalls begging his mother to grant him permission to assume the paper route from his older brother who graduated from high school in 1948 and left for pastoral studies at Houghton College in New York. However, she remained very protective of her young son, having lost two of her children in 1936, and would not give in to his impassioned requests in an effort to keep her young son closer to home for just a little while longer.

“That was a real disappointing situation because I remember that my brother did quite well with that route and I thought for sure that I would be able to do the same and make some money,” he affirmed.

Seeking another means by which to earn a little money on his own, he tried selling greeting cards door-to-door in his local neighborhood but his mother, ever fearful something might happen to her youngest child, made his older brother accompany him on his sales activities.

He soon received a “hand-me-down” bicycle and began traveling around the community raking yards to earn a little extra spending money. For many young children who were approaching their teenage years, the bicycle was a device that offered a new level of freedom, providing them the means by which to travel greater distances from home for a range of purposes. For an adolescent Lockwood, the bike, along with the acquisition of a little more age, resulted in his finally receiving the blessing of his mother to go out in the community and find a part-time job. He soon began pedaling his bike three or four miles in “one direction away from the house” to work on a local family dairy farm. Other times, he would travel “six miles or so” in the other direction to work on another dairy farm while also assisting local farmers in putting up hay harvested from the fields, which was later used to feed their cattle in the winter months.

Bryce Lockwood, center, is pictured in a family photograph taken in the mid-1940s. In addition to his father, Raymond Sr., and his mother, Iva, his older brother, George, and his sister, Edith, pose in the background. Courtesy of Bryce Lockwood

The family attended the Nineveh Presbyterian Church, where his mother served as a Sunday school teacher for a number of years. His mother had been raised in the Baptist denomination while his father was raised Presbyterian; however, as Lockwood explained, many in rural communities would attend whichever church was located nearest their homes, as was the case with the local Presbyterian church. Religious instruction and participation in church activities remained an important component of his upbringing. Although he clearly recalls memorizing the venerated Bible verse John 3:16, the underlying meaning of the verse was never explained to him—a circumstance that would later inspire his decision as to which college to attend.

Pictured in his 1957 graduation photograph from Afton Central School, Lockwood made the decision to continue his education by enrolling at the former Baptist Bible Seminary in Johnson City, New York.

Another early memory that remains indelibly etched in Lockwood’s memory was accompanying his mother on her visits to the graves of his two siblings who had died years earlier. It was during one of these “Decoration Day” visits to the Nineveh Presbyterian Cemetery that he paused to ask his mother an innocent question that several years later motivated his decision to provide a final honor to his deceased siblings.5

“On Decoration Day, my mother would visit the burial site of my sister and brother to place geraniums on their graves,” explained Lockwood. “I remember asking her the innocent question, ‘Where were their tombstones?’ With a tear in his eye, he added, “After a pause, she looked down and said, ‘We can’t afford a tombstone.’”

Decades later, the poignancy of the event he witnessed as a child would not fade from Lockwood’s memory; instead, it eventually grew into the inspiration for him to purchase a gravestone for the burial site of his siblings. He viewed it as a way of recognizing the years of anguish endured by his mother and to ensure the lives of his siblings, however brief they were, would always be remembered.

As he began the preparations for his graduation from Afton Central School in the spring of 1957, there was an event at his local church that provided him a little direction in what he believed to be his future calling—the ministry.

“As I had said before, while we were growing up, the church remained a central point of our lives; but even though they made great efforts to make sure we memorized the verses like John 3:16, they failed to make sure that we understood its true meaning and intent,” he said. “One day, we were visiting the First Baptist Church in Sydney, New York, and there were two couples from Bob Jones University there to present that day. During the service,” he continued, “they explained the meaning of John 3:16 and I said, ‘That’s me!’ And that just happened to be the day that I walked down the aisle and gave my heart to the Lord. It was also when I decided that I wanted to serve in the ministry,” he affirmed.

Faith, though a principal focus in his high school years, did not always overrule the wild streak that occasionally develops among young men with too much time on their hands in the hours that unfold after school and on evenings and weekends.

In the weeks after the Fourth of July, he and one of his otherwise unoccupied cohorts made the ill-fated decision to sneak onto the racetrack at the local fairgrounds and steal some high-powered fireworks. They set one off later that evening and, although the town marshal was patrolling nearby, they managed to escape detection… for the time being. The following year, however, the theft was discovered, resulting in a criminal record that would unexpectedly follow Lockwood into his Marine Corps service years later.

“The year after we stole the fireworks, friends of mine, whom I had given some of the fireworks to, decided they were going to set them off—and they got caught!” he bluntly explained. “When the town marshal questioned them about where they had gotten them, they ratted me out and I was charged with petty theft. Before I went to court, the marshal told me if I pleaded guilty, there would be nothing on my record about the incident.”

Lockwood did what was suggested by the local lawman and pleaded guilty to the petty theft in municipal court. He was ordered to pay restitution to the local fair association from whom the fireworks had been stolen. This required working a number of odd jobs throughout the community for the next several months to make the required payment, all the time believing there would be no official record of the incident.

Halloween provided yet another opportunity for Lockwood and a group of his young associates to engage in youthful shenanigans. Because of his mother’s home-based sales business, a number of cardboard boxes that had been used to ship products were lying around the home. The boys thought it would be great fuel for a massive bonfire. Later that particular evening, seeking the ideal spot for the planned conflagration, they chose to erect a cardboard mountain in the middle of the street in front of the Lockwood family home.

“Those boxes were stacked in such a huge pile that it’s amazing we didn’t burn the entire town to the ground,” he chuckled in mirthful reflection. “The trees under which we had stacked all those boxes were so badly charred from the flames that they didn’t grow leaves again for the next several years.”

Fortunately, their mischievous activities were rare; instead, Lockwood and his friends began to focus their attention on more productive efforts. During their senior year of high school, his class sold ice cream bars and various other treats in the cafeteria during lunch to raise the funds necessary to take a senior trip at the end of the year. They raised enough money to make the journey to Washington, DC, and visited a number of historical sites along the way, including Gettysburg National Military Park, where the bloody Battle of Gettysburg unfolded during the Civil War in July 1863.

“That was a very impressive and eye-opening experience for me since all four of my great grandfathers and two of my great, great grandfathers fought for the Union during the Civil War,” he said.

When they arrived in Washington, DC Lockwood recalls that the students were given a tour of the Capitol and also received the privilege of seeing Congress in session—an unexpected opportunity to witness the introduction of a man who would soon become president of the United States.

Lockwood explained, “We were on a tour of the Capitol [in May 1957] while Congress was in session and the tour guide pointed out a gentleman and said, ‘You all should keep an eye on that congressman because he is going places someday.’ The gentleman he happened to point toward was a young Senator John F. Kennedy.”6

In addition to being a period of adventure, high school was when Lockwood sought to map out a defined plan for his future—a challenge that has faced young persons for time immemorial. It was a period, he said, that resulted in the unexpected introduction to a lovely young woman who happened to “catch his eye,” quickly becoming the sole object of his affections for decades to come.

“My older sister Edith married Gordon Jones, who had a younger sister named Lois,” Lockwood grinningly explained, while reflecting on the early days of dating the woman who became his bride. “So, basically, I met Lois through my sister because our families would get together at different events throughout the year,” he added. “I finally found the courage to ask her out and we first began dating back in 1956.”

In the months following his enlistment, both Raymond and Iva Lockwood were supportive of their son’s decision to pursue a career in the United States Marine Corps, even suggesting it to other young men in their community. Iva Lockwood is pictured here in September 1960 receiving an “Honorary Recruiter” recognition from her son’s recruiter, Sgt. John Brown, for helping encourage the enlistment of five Marines.

Upon graduation from high school in May of 1957 in a class of thirty-one students (the class began with thirty-three students at the start of the school year but two failed to complete the requirements for graduation, Lockwood explained), the young man from the small community of Afton made the decision to enroll in Baptist Bible Seminary in Johnson City, New York. The seminary was located approximately forty miles from his home and has since become Clarks Summit University. His parents weren’t able to support his education there, so the aspiring student had to find employment to help cover the expenses of boarding and tuition.7

For five nights a week, he worked at a local bowling alley, resetting the pins at a time before automation replaced these manual processes.

Chuckling in reflection, he said, “I made six dollars a night doing that and it was a one-and-a-half-mile walk from the boarding house where I stayed to the bowling alley where I worked.”

His best efforts and yearning to pursue an education in the ministry soon met an unwelcome realization. He discovered that, regardless of any means he might have to fund his education through work in the evenings while pursuing the path to becoming a preacher, this desire was compromised by the realization that he was not poised to focus on the necessary academic aspects of the educational experience.

“I hated writing the term papers, pure and simple,” he flatly admitted.

His educational endeavors would for a time have to percolate on the back burner because he made the decision to leave school. Since he had spent the last few years working whenever he found an opportunity, Lockwood did not hesitate in locating appropriate employment. A short time later, he was offered a job with the Ohio Equipment and Supply Company, which had the contract to remove the old rail system that had once been used by the New York, Ontario and Western Railway—a company that disbanded in 1957. For a brief time, the erstwhile college student was actively engaged in salvaging the steel from the rails and the copper wire from the telegraph lines of the once sprawling transportation network. The work soon subsided and he was laid off in February 1959.

“Not long after that, I was hired by F & K Lewis—a construction company—that also had a concrete block plant,” Lockwood said. “I can remember working with them and spent a large amount of my time tearing down an old apartment complex and building that became a Sinclair Gasoline service station, basically just salvaging whatever we could from the site.” He unenthusiastically continued, “It was really tough work in the middle of winter… blindingly cold. I later discovered that the owner had underbid a contract for a high school and was in steep financial trouble, not a good situation for my future employment prospects.”

His father, Lockwood explained, realized what was happening with regard to the company’s future and sagely informed him that he might want to take a few moments to consider his employment prospects and what he was going to do before he was without a job.

Lois mirthfully interjected, “I told him that we’re not getting married until he had a steady job!”

Lockwood soon thought of the military as an honest career possibility and he attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army, inspired by the service of uncles who had once been soldiers. Setting his sights high with the goal of becoming a member of the Special Forces, Lockwood excelled at all of the tests except for the eye exam, which he failed.

“They sent me back home in early 1959 and I soon ran into my Army recruiter,” he said. “The recruiter told me that if I still wanted to get in the military, to come by his office and see him. When I did stop by his office, he said to go and have my eyes checked at a local optometrist, get a new set of glasses, and I did that. The next time I stopped in to see him,” he paused, “he walked me down the hall to the Marine recruiter’s office.”

The Marine sergeant, Lockwood recalled, did not seem enthused by the enrollment of a prospective recruit; instead, he appeared more interested in puffing on a large cigar and focused on reading the newspaper clasped in his hands.

“After he heard that I was there to enlist, he gruffly pointed toward a table and said, ‘Fill out those papers over there.’ Since I had my new glasses, I passed my Marine Corps examination. I can remember taking the Armed Forces Qualification Test—there were 100 questions—and I managed to ace it! I didn’t think that it was a big deal at the time but, when I was home on leave from training months later, I stopped by the recruiter’s office and saw on the front page of the Navy Times where a sailor was highlighted for having aced the test.”

Many parents throughout recent history have been racked with worry and concern when one of their children declared their intent to enter the service, stirring up a flurry of worries for their safety and the potential for the youth to be placed in a combat situation. Lockwood’s parents recognized the value of the education he might receive in the military and fully supported their son’s decision. In fact, their support blossomed to the extent that they ardently encouraged several young men from their community to consider the Marine Corps, resulting in five enlistments and Lockwood’s parents being recognized as “Honorary Recruiters” for their efforts.

Oftentimes, those who enlist become disdainful of their recruiters because they may have been deceived or promised one career field and then unexpectedly thrust into another. For Lockwood, the individual who was responsible for ushering him through the enlistment process, Sergeant John Brown, would become a close friend and later stood by his side during one of the most important days of his life.

Inducted into the United States Marine Corps at the Federal Building in Albany, New York, on April 1, 1959, Lockwood soon boarded a train in Albany along with a group of recruits making the trip to New York City, where they took on several more recruits. The group then made their way to Philadelphia to pick up additional men seeking to become Marines, before making their way to the train station at Yemassee, South Carolina.8 The anxious young men then scurried aboard buses and traveled to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina, arriving in the early morning hours of April 2, 1959. They were an unproven collection of America’s youth from a number of communities and backgrounds from throughout the eastern parts of the country. At the time, they were unaware of the depth of experiences they were soon to endure when immersed in a brief—yet intense—cycle of military training that would draw them together and mold them into the newest members of the United States Marine Corps.

1 According to Lockwood, their German shepherd, “Babe,” was a grandniece of the famed “Rin Tin Tin,” the dog that appeared in a number of popular films in the 1920s.

2 National World War II Museum, Research Starters: The Draft and World War II, www.nationalww2museum.org.

3 According to U.S. Census data, the population of Afton, New York in 1940 was 1,848. Ten years later, the population had increased to 2,047.

4 June 19, 2004, edition of Press and Sun-Bulletin.

5 Decoration Day is a holiday that emerged after the Civil War and consisted of decorating the graves of fallen servicemembers with flowers. It became an official federal holiday in 1971 and is now known as Memorial Day.

6 John F. Kennedy served as U.S. Representative for the 11th Congressional District of Massachusetts from 1947 to 1953 and represented his state as a U.S. Senator from 1953 to 1960. He was sworn in as the thirty-fifth president of the United States on January 20, 1961.

7 Baptist Bible Seminary was later moved to Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania, in the late 1960s when there developed a need for a larger campus. The school was later named Baptist Bible College of Pennsylvania and in 2016 became Clarks Summit University. Clarks Summit University, Faith & History, www.clarksummitu.edu.

8 The use of the Yemassee Train Station by the U.S. Marine Corps ended in 1965. Estimates indicate that between 1915 and 1965, more than 500,000 recruits passed through the station on their way to training at Parris Island. July 22, 1997 edition of the Greenville News.