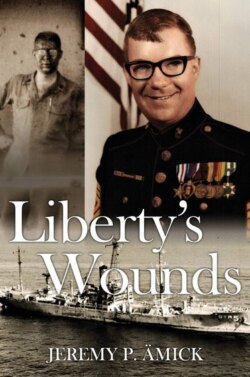

Читать книгу Liberty's Wounds - Jeremy Amick - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Corps Is Calling

“I remember our bus being stopped at the front gate [of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina] and the gate guard stepping onto the bus, loudly proclaiming, ‘Ah… look at all these girls. Aren’t they in for a good time!’” – Lockwood describing his arrival at his basic combat training on April 2, 1959.

When pulling up in the bus at the main gate of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) at Parris Island, South Carolina, and preparing to take the initial steps toward what would explode into several intense weeks of basic combat training, Lockwood and his fellow recruits did not fully fathom the strenuous military training regimen awaiting them in the ensuing weeks.

Located in the harbor of Prince Royal Sound, the “deepest natural harbor south of New York,” Parris Island possesses an extensive history and was the site of a coaling station for the U.S. Army during the Civil War. In the decades that followed, the U.S. Navy developed the area into a coaling and supply depot, in addition to taking the steps to enlarge the site to also serve as a naval repair facility. Although the history of Marine Corps recruit training on Parris Island existed in some form as early as 1903, it officially unfolded in 1915, at which point the Marine recruit depot was moved there from its previous location at the Norfolk Naval Station in Virginia. The first recruits arrived at Parris Island for training aboard the USS Prairie in October 1915 and, in the same year, the train depot was established at Yemassee, South Carolina, to serve as a receiving point for young men traveling from recruiting stations throughout the eastern and central regions of the country.9

“I remember our bus being stopped at the front gate of Parris Island and the gate guard stepping onto the bus, loudly proclaiming, ‘Ah… look at all these girls. Aren’t they in for a good time!’” With a chuckle, Lockwood added, “Of course, I was scared to death because I didn’t know what to expect… as did most of the guys that were traveling on the bus with me.”

Shortly after their callous welcome, the recruits began their in-processing at the new training site by first going to the receiving barracks. Their indoctrination into the Marine Corps continued with having their heads shaved, being fitted for their initial allotment of uniforms, and receiving an untold number of immunizations. Throughout the process, the recruits were subjected to an excessive amount of yelling by various sergeants whose mission it was to take a ragtag group of undisciplined youth and transform them into hardened fighting machines. Once they were assigned to their training barracks, Lockwood’s platoon was given a formidable introduction to the three seasoned drill sergeants who would be responsible for their training—two of whom were veterans of the Korean War (one of those two, Lockwood said, had years earlier earned a Bronze Star for his service in the deadly Battle of Chosin Reservoir10).

“Back in those days, they had what was referred to as a ‘thumping,’ which essentially meant that the drill sergeants could pound the fire out of you [strike a recruit], but they aren’t allowed to do that anymore without getting in a lot of trouble,” Lockwood said.

He first discovered the blunt reality of “thumping” during a brief course of instruction his company was provided on the Browning automatic rifle. During a pause in the presentation, Lockwood asked a question about the functioning of the mechanism of the rifle, after which one of his drill sergeants came over and explained it to the group he was training with at the time. An enthusiastic Lockwood, finally grasping the working of the mechanism after the terse explanation he had just received, affirmed his newfound comprehension by innocently muttering “Yeah!”

A group of raw Marine recruits disembark from a train at the station in Yemassee, South Carolina, in the 1950s. Once Lockwood and his group of fellow trainees arrived at the station, they boarded buses and proceeded to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, located approximately an hour’s ride to the south. U.S. Marine Corps photograph

“I should have responded ‘Yes, sir!’ instead of ‘Yeah!’” he recalled. “No sooner than the word left my mouth, the sergeant reached over and smacked me on the side of the head. It really didn’t hurt all that much but I can assure you that was the last time I got careless with what I said around him.”

In addition to a “lot of marching,” map reading, field exercises, and physical training, the raw recruits were also given rifle instruction on the M-1 Garand—a weapon that had served as a standard U.S. service rifle during both World War II and the Korean War. On one occasion, they were marched to the rifle range and directed to an area behind the backstop where the rifle rounds fired at the targets would impact. In the previous year, a flash flood had struck the training site and resulted in the drowning deaths of several recruits in the vicinity where Lockwood and his fellow recruits were conducting their marksmanship training. Upon the arrival of Lockwood’s training company at the rifle range, one of their drill sergeants raised his arm and pointed to an area behind the abutment, callously remarking, “You girls want to go for a swim? This is where it happened.”

General Alfred M. Gray Jr., the 29th Commandant of the United States Marine Corps, said many years ago, “Every Marine is, first and foremost, a rifleman. All other conditions are secondary.”11 This famous quote, though spoken in the years after Lockwood went through his own training, characterized the mindset of the Marine Corps—a famed “one shot, one kill mentality.” As such, qualification with a rifle has endured throughout the decades as a basic tenet of Marine Corps training. Despite the immense number of hours aspiring Marine recruits were required to invest on the rifle range, it did not, however, result in Lockwood achieving a grand result in his own qualification record while in basic training.

“I didn’t do so well at the range,” he flatly admitted. “There was a piece screwed up on my rifle—maybe the sight aperture… I don’t really remember. I took it to the armorer to turn it in to get worked on the day before our official qualification, but I don’t think it really got fixed.” Hesitating, he added, “But I did qualify… and I guess that’s all that matters.”

Basic training was not only an opportunity for raw recruits to be forged into fighting Marines, but it also became a period when they were saddled with responsibilities of a less glamorous—yet necessary—nature, such as kitchen police (KP). KP was a rather lackluster circumstance during which the recruits would perform a range of duties to assist the cooks and staff at the mess facilities, often associated with such mundane tasks as peeling large quantities of potatoes, washing and drying dishes, and mopping floors. While in basic training, Lockwood spent two weeks on mess duty and was placed in charge of four of his fellow recruits, all of whom were assigned to the mess facility at the quarters for the senior drill instructors. As a component of his responsibilities, Lockwood was assigned the task of preparing the coffee, an undertaking that the mess sergeant deemed had been performed in a less than adequate manner.

“The mess sergeant came over to me and asked what I had done to the coffee because it was coming out too weak, and I quickly explained to him the process I had used to brew it. He barked, ‘You did what?’ and smacked me on the side of my head with a coffee cup he was holding. I began bleeding profusely and then he yelled, ‘Get out of here! You’re getting blood all over my clean deck!’”

The stunned recruit bolted for the “head” (restroom), where he quickly snatched a handful of towels in a rather futile attempt to stop the gash on the side of his head from bleeding. A short while later, the mess sergeant came in to assist, but when he was unable to get the bleeding to stop with an ice pack, he decided it was best to send Lockwood to the sick bay to receive more experienced medical treatment.

This real-photo linen postcard of the main gate area of Camp Lejeune has a date stamp of 1956—three years prior to Lockwood’s arrival for basic training. He would spend several weeks at the North Carolina base before moving to nearby Camp Geiger for additional infantry training. Courtesy of Jeremy P. Ämick

“The medical corpsman who treated me asked me what I had done to end up with such an injury,” Lockwood remarked. “I said, ‘Sir, the private bent over to pick up a sponge and hit his head on the corner of a steel table.’ The corpsman then looked at me with a disbelieving grin and said, ‘Yeah, sure you did.’ I could easily have gotten the mess sergeant in a lot of trouble for striking me with that cup but I let him off the hook.” He added, “I ended up getting several stitches on the side of my head because of it.”

After returning to the barracks from his mess duty, Lockwood was using the head when his drill instructor walked in and noticed the white bandage taped on the recruit’s head. With a pause, the sergeant yelled, “What happened to you, private?!” Calling upon the response he had provided to the medical corpsman a short while earlier, Lockwood said, “Sir, the private bent over to pick up a sponge and hit his head on the corner of the steel table.” The drill instructor then grinned at him and, with a similar look of disbelief, responded, “Yeah, sure you did.”

The mess sergeant later realized the gravity of his mistake and recognized the fact that the young recruit had chosen to take the high road by not complaining about having become a victim of the NCO’s rage. For the remainder of the time he was assigned to the mess detail, Lockwood explained that he could do no wrong in the eyes of the mess sergeant and was oftentimes offered special cuts of meat and other foods that were not offered to his fellow recruits. As Lockwood noted, he chose not to accept any of these unsolicited gifts out of fairness to the fellow privates with whom he served while on KP.

Throughout the remainder of his training cycle, Lockwood strived to maintain a low profile and continued to perform the assigned training functions to the best of his ability. However, he believes that his reluctance to pursue reprisal for the injury he received and his decision to shield the mess sergeant from any disciplinary actions may have provided some motivation for the recommendation for his promotion to private first class on July 1, 1959, during the waning days of his basic training—an advantage (with increased rank comes a meager increase in pay) granted to only those new Marines graduating in the top ten percent of their basic training class.

Camp Geiger, North Carolina

During midsummer 1959, Lockwood and his fellow trainees finally achieved the coveted title of “Marine” when graduating from their basic training. But there was little time for celebration because the hardened young Marines were loaded on a bus and sent on their way to Camp Geiger, North Carolina, to embark on several weeks of combat infantry training.

According to the Cultural Resources Management section for Camp Lejeune, Camp Geiger was located on the west end of Camp Lejeune and was initially known as “Tent Camp No. 1.” Its beginnings dated back to initial construction in April 1941, establishing a housing site area for the influx of recruits during troop build-ups in World War II. Camp Geiger received its name in the early 1950s in honor of the late Roy Stanley Geiger, a pioneering Marine Corps aviator and four-star general who served during both World War I and World War II.12

“There really didn’t seem to be much change from the time I had spent in boot camp to the early weeks of my stay [at Camp Geiger],” said Lockwood, describing his regimen of training. “Once again, I was assigned to KP duty for a couple of weeks and was placed in charge of a group of my fellow Marines who were serving on mess duty at the senior staff NCOs’ (non-commissioned officers) quarters,” he sullenly recalled.

When their training began in earnest in mid-June 1959, Lockwood was appointed to serve as a squad leader while he and his Marine counterparts were brusquely introduced to the commanding officer, Captain Holmes, whom he described as a “seasoned combat officer who fought on Saipan and Tinian in World War II.”

Lockwood went on to explain, “Holmes wanted us to be the toughest and, as part of his grand plan, had us out there running on base every morning. He would often bark at us a quote that he said came from his inspiration and a great Marine Corps leader, Chesty Puller. It went something like, ‘I want an outfit that can march all night, double-time the last three miles and be ready to fight when they get there.’ Those,” Lockwood added, “were words Holmes truly believed.”13

A young Marine negotiates a rudimentary obstacle course at Camp Geiger, North Carolina in the early 1960s. The camp continues to serve as one of two infantry schools for the Marine Corps. Marine Corps photograph

With their infantry training occurring in the summer months, certain aspects of their experiences became rather disenchanting in his reflections, specifically those related to the times he and his fellow recruits were required to fulfill the role of an opposition force for Marine Corps Reserve units performing their annual training periods. As he recalled, the units had at their disposal what appeared to the trainees as the newest and nicest weapons and equipment. Armed with only their bulky and outdated M-1s, in addition to lacking in the military experience of the reservists, Lockwood and his training company endured their rite of passage and discovered the feelings of defeat while often fulfilling the sullen role of casualty while the reservists honed their military skill sets.

Their combat infantry training maintained its intensity and Lockwood was summarily forged into a hardened and fierce U.S. Marine during the instruction he received on both defensive and offensive operations in addition to live-fire exercises that inculcated the skills that would be needed by Marines facing the unexpected challenges arising in a combat environment. Their weeks of concentrated training also included a number of weapons demonstrations, instruction on working with demolitions, landmine warfare, hand grenade training, and participation in reconnaissance patrols.

Captain Holmes, in an effort to provide a little downtime to his Marines while at the same time reinforcing many of the military training methods they might someday need to survive in combat, occasionally brought a Jeep to the training area after a hard day of training and ordered his Marines to gather around for an informal lesson.

“He had a movie projector set up on the back of his Jeep and would set up a screen to show combat footage from the battles that took place on Saipan,” Lockwood reflected. “I didn’t realize the importance of the films at the time—and wouldn’t until I got to Vietnam years later—but he was using it to demonstrate the importance of close air support.”

In the latter days of his combat infantry training at Camp Geiger, Lockwood received orders for communications training in the state of California. However, as his combat training finally came to an end in August 1959, he was granted several days of leave, which he used to return home and reconnect with family and his girlfriend, Lois. The off-duty time he spent in the company of friends and loved ones seemed to pass quickly and he was soon on a bus to make the return trip to Camp Geiger. Following a week of being assigned to a casual company and “sitting in the barracks, cleaning our rifle stocks and shining our shoes,” he was sent to a nearby airport to board a leased four-engine prop plane bound for the West Coast.

Imperial Beach, California

“They flew me into San Diego and, not long after I got there, they assigned me to a casual company and I spent a couple of weeks there with very little to do,” Lockwood said. “Then they moved a group of us down to Imperial Beach to begin several weeks of communications training.”14

While in the basic communications training course at Imperial Beach, Lockwood was selected as “Military Honor Man” on four different occasions. For this, he earned several Friday afternoons off from the rigors of schoolwork.

Located approximately five miles northwest of Tijuana, Mexico, Imperial Beach is the southernmost city in California. In the years prior to World War II, Imperial Beach was the site of Fort Emory—a U.S. Army post that was “part of a system of defenses along the West Coast, which grew out of plans made by the Army Coastal Artillery Corps between 1915 and 1936.” During much of World War II, 155-millimeter artillery pieces contributed to the coastal defense mission of the site. Later in the war, many of the batteries stationed at Fort Emory were moved to other locations and a portion of the fort was transferred to the U.S. Navy in 1944 “to expand their radio receiving station.” Many changes were made to the area in the years that followed and, in 1950, the U.S. Army transferred the rest of Fort Emory to the U.S Navy and the area was consolidated into the Imperial Beach Radio Station. A few years prior to Lockwood’s arrival, a communications technician training school was established at Imperial Beach, providing both basic and advanced courses.15

During the strenuous cycle of basic training, Lockwood had undergone in the months prior to his arrival in California for communications training, he and his fellow recruits were required to fill out paperwork and complete a variety of tests to determine their specific competencies, aptitudes, and interests. Lockwood recalls achieving a high score in most of the fields that were measured, and listed as his first choice for a training and duty assignment the construction field, since he had gained such experience prior to enlisting in the Marine Corps. As a secondary specialty, he chose communications, which is where, he jokingly recalled, the military chose to place him.

Upon arrival at the Naval Communications Training Center in the early fall of 1959, Lockwood and other Marines assigned to the training were taken to their barracks at the nearby Coronado Naval Amphibious Base. From there, they would daily travel to their basic communications training aboard a bus.

“Imperial Beach had been the site of an old Army coast artillery base in World War II and you could still see where there had been some foundations for the old barracks,” he said. “We were there for several weeks to undergo basic communications training. In the training, we had long wire antennas for picking up the signals from ships, direction-finding technology and, of course, the fundamentals such as Morse code and typing were taught as well.” He added, “They also provided us with some training in rudimentary communication security measures… such as the best way to safeguard sensitive and classified information.”

Basic typing courses were also introduced as an integral part of the early days of their course since many of the trainees had never learned to type during their years in high school. With an estimated two dozen students assigned to the course—four of whom were Marines and the remainder U.S. Navy personnel—Fridays presented the trainees with a coveted opportunity to earn a little time off from the rigors of both military life and their schoolwork.

“On Friday mornings, they would do an inspection outside the barracks,” Lockwood said. “Then they would pick someone from the class to go before a group of senior officers and the group would look at your uniform—little things like lint or a speck of dirt could disqualify you from being selected. If you survived the judging and were chosen,” he added, “then you were considered the ‘Military Honor Man,’ and you would be given that Friday afternoon off. I think I won the honor four times while I was there.”

He continued to communicate regularly with his intended, Lois, by writing letters to her whenever he found an opportunity, although he mirthfully admitted he was more committed to writing letters than was his fiancée. However, he also found a few opportunities to visit with her by telephone since she was employed as an operator for a telephone company in New York.

“We talked on the telephone a few times and, when she was on duty, she would try to call me,” he recalled. “But I was living in a barracks along with several dozen guys and there happened to be only one pay phone in the entire building. Most of the time I wasn’t able to catch her calls.”

The basic communications portion of their training cycle came to a close in the days before Christmas but, as Lockwood attempted to acquire his interim security clearance so that he could move on to the advanced component of the training, he learned that an incident from his youthful days back in New York would cause him an unexpected delay. For all military members who might be placed in a situation where they might possibly be exposed to classified information, a thorough background investigation is conducted to uncover any potential concerns that make an individual more susceptible to compromising such protected information.

“Not only did the investigation for my security clearance result in the investigators speaking to my family, but they even spoke to friends of my family, neighbors and some of my teachers from back in high school,” Lockwood said. “Somehow, during the background investigation, they uncovered documents and information regarding the petty theft charge I received back when I was fourteen or fifteen years old and had stolen those fireworks on a lark. Although any reference to the infraction was, in my understanding, supposed to have been removed from my record, they somehow were able to locate that information and it held up the approval of my security clearance.”

Lockwood, far right, is pictured on April 1, 1960. while participating in a color guard during a retirement parade held for an executive officer assigned to the communications school at Imperial Beach.

While the investigation of his background continued, the Marine was prevented from attending his advanced communications training and was kept busy by being placed on temporary duty with the shore patrol. As noted in the booklet The U.S. Navy Shore Patrol printed in 1964, the establishment of shore patrols often occurred “when the number of military personnel frequenting an area is so large that civil law enforcement authorities may need help to maintain peace and order, or when patrols are needed to safeguard the health and welfare of Navy and Marine Corps personnel.” Not only were the patrols implemented to “preserve order among members of the Armed Forces who are on leave or in a liberty status,” they also had the responsibility to “apprehend deserters and members of the Armed Forces who are AWOL [absent without leave].”16

“During the day, one of the duties I performed while with the shore patrol was to fill out the watch bill,” he said. “Essentially, it was maintaining the assignment listing for those who were to serve on security and fire watch details at the barracks.”

The evening shifts of his shore patrol duty provided him with the most interesting experiences while he and three other Marines would take turns patrolling in a 1951 Ford pickup truck, checking out the antenna field and the remainder of the base.

“I was on patrol one evening and it was well after curfew… probably around 1:00 a.m. or so,” he said. “I saw this guy strolling up the beach, which was pretty common for sailors and Marines trying to sneak around the security gate and make their back onto the site after their curfew. I pulled up and asked him for his identification and his pass.”

He discovered the tardy sailor did possess a valid identification but his pass was not acceptable since it had expired several hours earlier. At that point, Lockwood instructed the beach walker to crawl into the passenger side of the shore patrol truck.

“The routine was to stop by the administration building where the officer of the day was located and have the individuals that we apprehended on our watch written up for disciplinary actions. To be honest with you, the guy hadn’t been drinking or anything like that and I think he had just been out on a date. So, when I approached the administration building, I just drove on by and dropped the guy off at his barracks. Then I handed him his identification and pass and told him not to get caught by the fire watch when he sneaked back to his bunk.”17

Several weeks later, after the Naval Investigative Service completed their thorough background investigation, Lockwood was approved to receive his final security clearance and began his advanced communications training at Imperial Beach in February 1960. He and his fellow classmates packed their belongings and left the barracks at Coronado to move into barracks on the grounds of Imperial Beach. As the final months of his initial training approached, the Marine and his girlfriend took the bold next step by formalizing their relationship.

“Mr. and Mrs. Earl E. Jones of Castle Creek (New York) announce the engagement of their daughter, Lois Edna, to Pfc. Bryce Franklin Lockwood, U.S. Marine Corps,” reported the Press and Sun-Bulletin in its April 24, 1960, edition.

“When we went into the advanced training, that’s when we found out that our primary targets were the Soviet Union and China,” he explained. “The first day we walked into the classroom, we all noticed that there were typewriters on the table with plastic covers pulled over them. The school supervisor said, ‘Now it’s time to tell you what you’re going to be doing when you finish this school.’ He told us to walk over and remove the covers from the typewriters and when we did, that’s when we realized that all of the keys on the machines were in the Cyrillic alphabet.” (The Cyrillic script was a writing system in use by several nations, the most notable of which was the former Soviet Union.)

The U-2 spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers, pictured, was shot down by a Soviet surface-to-air missile on May 1, 1960, while Pfc. Lockwood was in advanced communications training at Imperial Beach. National Park Service photograph

The Strategic Air Command (SAC), in 1957, three years prior to Lockwood’s arrival at Imperial Beach, recognized the seriousness of the aerial threat posed by the Soviet Union and, as a response, elevated their nuclear delivery capabilities by establishing a ground alert. This consisted of keeping “B-52s [bombers] armed and ready to take off at first warning of a Soviet attack.” In 1960, while Lockwood was in his advanced communications training, “SAC made its ground alert more stringent: ‘One-third of SAC achieved 15-minute ground alert status by August 1960,’ meaning that 150 (out of 450) nuclear-armed B-52s would be in the air before Soviet ICBMs could strike SAC airfields.”18 During this period, there also came the realization of emerging Soviet naval developments, the primary of which were submarines armed with nuclear missiles that had the capability of striking the United States. This threat required military personnel not only in the Air Force, who were focused on mitigating the potential aerial threats, but U.S. Navy and Marine Corps personnel such as Lockwood, who were trained to gather and interpret varied types of naval intelligence.

The advanced training quickly introduced Lockwood and the other students to “communications intelligence by providing us with the skills they would need to monitor the message traffic of Soviet vessels,” he said. Class members quickly learned the Russian script and were then tested on the previous week’s training by taking a test every Friday morning. If a Marine or sailor “aced” a test, Lockwood said, the instructor would give the student the afternoon off from class as a reward for their achievement.

“I did well on many of the tests and was given several afternoons off,” Lockwood remarked. “But, on Friday afternoons, the instructor would also show Victory at Sea films for those who didn’t perform so well on their tests and I would often stay just to watch those films because I really enjoyed learning about World War II history.”19

In addition to receiving instruction on several aspects of communication that would later help them become successful in gathering intelligence from the Soviet Union, the students of the advanced communications class were briefed on ferret flights—a codename that had been given to reconnaissance missions flown by Cold War aircraft such as the legendary U-2 spy plane. Developed by Lockheed Martin, the U-2 was at this time a relatively new aircraft and had completed its first flight only a few years earlier, in 1955. A high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, the covert spy plane was, during its early years of operation, flown under the authority of the Central Intelligence Agency. The aircraft quickly entered an operational environment where ferret missions were not exempted from the threat of enemy attack. Navy reconnaissance aircraft had twice become targets for attacks when “MiG-15s shot down a P2V over the Sea of Japan September 5, 1954” and a second was attacked “near the Bering Strait July 23, 1955.”20

“I remember the instructor pacing around our classroom on a Monday morning, just after we had been briefed on ferret flights the previous week. He stopped in his tracks, turned and said, ‘Did you all follow the news over the weekend?’ He was speaking about Francis Gary Powers, who had just been shot down over Russia.”

On May 1, 1960, the U-2 spy plane flown by Francis Gary Powers was shot from the sky while operating in Soviet air space. It was an ultra-sensitive period in Cold War relations between the U.S. and Russia, with each country concerned about the other’s nuclear capabilities, while at the same time a heated arms race continued to unfold. Five years prior to Powers’ failed overflight and subsequent capture, President Eisenhower proposed to his Soviet counterpart, Nikita Khrushchev, during a conference in Geneva, that each county be afforded the opportunity to fly over the other’s airspace to inspect the nuclear facilities and launch facilities of the other—a proposal the Soviets declined, choosing instead to move forward with their development of intercontinental ballistic missiles.

This was one of the failed diplomatic situations that served as an inspiration for the development of the U-2 spy plane. With a flight ceiling of 70,000 feet, the aircraft was believed to be able to pass over the Soviet Union at height undetected by their radar. The first overflight of Soviet territory occurred on July 4, 1956, followed by recurrent reconnaissance throughout the period of the next three years. The ensuing years delivered the startling revelations that the Soviets were able to detect the high-flying spy planes, demonstrated by their use of the surface-to-air missile that had brought down the aircraft piloted by Powers. The young aviator was able to eject from the U-2 and parachute to safety; however, after reaching the ground, he was taken into custody by the KGB and interrogated. Fearful that the Soviets would use the opportunity to demonstrate they now had proof the U.S. was making unauthorized incursions into their air space, which might be considered an act of war, U.S. officials quickly claimed that “the U-2 had been conducting a routine weather flight but experienced a malfunction of its oxygen delivery system that had caused the pilot to black out and drift over Soviet air space.”21

Wreckage of the aircraft recovered by the Soviets provided all the proof they needed to reveal that the aircraft was used for spying but President Eisenhower, with full knowledge the Soviets maintained operatives within the United States to gather intelligence, refused to issue an apology for the incident. Days later, however, the president conceded that he was aware of the spy program yet countered with the assertion that such programs were necessary for the safety of the United States and would continue as part of the country’s intelligence-gathering efforts. A Soviet court eventually convicted Powers as a spy and issued a sentence of three years in prison and seven years of hard labor. As America watched the diplomatic standoff unfold between the superpowers, February 1962 brought with it some closure to the situation when Rudolf Abel, a Soviet spy captured in the United States, was traded for both Powers and an American student who had been captured in East Berlin. The Powers incident became the end of diplomatic relations between Khrushchev and Eisenhower, with the presidency of John F. Kennedy delivering an entirely new bag of complicated Cold War challenges the following year.

On July 15, 1960, Lockwood was awarded his diploma for the U.S. Naval School, Communications Training Class “A,” having earned an impressive overall score of 99.3 from the intellectual investment he made in training. The following month, the 564th Strategic Missile Squadron at Francis E. Warren Air Force Base became “the first fully operational ICBM squadron” with six Atlas missiles that were prepared to launch.22 With many working parts comprising the complex machine of Cold War defenses for the United States, men such as Lockwood were at the time viewed as an integral component of the secretive preparations that would help the nation garner insight into the potential plans and threats brewing in the Soviet Union. This looming danger would, in the coming months, influence the young Marine’s entry to a specialized language training program that would continue to build upon much of the focused instruction he had received while stationed at Imperial Beach.

9 The Official Website of the United States Marine Corps, MCRD Parris Island, www.marines.mil.

10 The Battle of Chosin Reservoir is considered a defining moment for not only the Korean War, but also the Marine Corps. It helped characterize the stalwart spirit of the Marines who, despite being surrounded by overwhelming enemy forces in late November and early December 1950, were able to fight their way through mountain passes and reach transport ships along the coast.

11 General Alfred M. Gray Jr. served as the 29th Commandant of the United States Marine Corps from July 1, 1987, until June 30, 1991, when he retired with forty-one years of military service. The Official Website of the United States Marine Corps, “Every man a rifleman” begins at recruit training, www.marines.mil.

12 The Official Website of the United States Marine Corps, Camp Geiger, www.lejeune.marines.mil.

13 Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller rose to the rank of lieutenant general during his career spanning distinguished service in both World War II and the Korean War. He remains the most decorated Marine in U.S. history.

14 A casual company is a temporary administrative military unit that holds personnel who are pending further assignment to another unit or those who may be awaiting another form of action such as discharge.

15 Silver Strand Training Complex, Environmental Impact Statement, 3.13-8.

16 The U.S. Navy Shore Patrol, Mission of Shore Patrol, 1.

17 The fire watch, in military lexicon from decades past, was a service member who was appointed to watch for an outbreak fire and to alarm anyone sleeping in the affected barracks or structure. However, it now generally refers to a sentry who watched for any suspicious activity while others sleep, such as individuals who might choose to leave the barracks for unauthorized liaisons.

18 Press, Calculating Credibility, 88.

19 Victory at Sea was a twenty-six-episode television series that aired between 1952 and 1953, predominantly comprising newsreels highlighting several major naval campaigns of World War II.

20 Anderton, The History of the U.S. Air Force, 150.

21 Department of State: Office of the Historian, U2 Overflights, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/u2-incident.

22 Shaw Jr. & Warnock, The Cold War and Beyond, 28.