Читать книгу Taming the Flood: Rivers, Wetlands and the Centuries-Old Battle Against Flooding - Jeremy Purseglove - Страница 24

ENCLOSURE IN THE NAPOLEONIC ERA

ОглавлениеWhat it felt like to be on the receiving end of such operations and the hammering that the landscape endured in those early years of the nineteenth century are painfully conveyed by another poet whose roots were in the East Midlands. By the Napoleonic era, when the war with France intensified the need for food, enclosure of common land by Act of Parliament began to replace enclosure by agreement. In 1809 an Act was passed for the enclosing of the parishes of Maxey and Helpston in Northamptonshire. One aspect of the landscape revolution that this entailed appears to have been major drainage works, which drastically modified the stream between the two villages, to create what is now known as the Maxey Cut. John Clare, in his poem ‘Remembrances’, describes the damage done to his parish by the axe of ‘spoiler and self-interest’:

O I never call to mind

Those pleasant names of places but I leave a sigh behind

While I see the little mouldiwarps hang sweeing to the wind

On the only aged willow that in all the field remains.

The ‘mouldiwarps’, or moles, are the bane of drainage men, since their tunnels play havoc with banks and channels; and even now, water authorities employ mole-catchers. Clare continues:

Inclosure like a Buonaparte let not a thing remain

It levelled every bush and tree and levelled every hill

And hung the moles for traitors—though the brook is running still

It runs a naked stream and chill.42

The solitary willow, the gutted brook: these were the things that Clare picked out as the climax of his catalogue of casualties in this, one of his finest poems. How absolutely it chimes with our modern experience of loss of a sense of place. In the mid-1980s, drainage contractors in the Midlands are still moving in on river valleys, starting with the stream itself and then clearing every adjacent hedge and copse as part of the same contract. The only differences Clare would notice are that machines have replaced axes, and that the moles are now gibbeted on barbed-wire fencing.

Clare’s contemporaries in the wetlands had reason to be concerned more for their own survival than that of moles and willow trees. In 1812 James Loch took over as Lord Stafford’s agent at Trentham in Staffordshire. He was later to become notorious as the scourge of Sutherland for his role in the highland clearances. Rather nearer to his employer’s family seat were the marshes of the Wealdmoors, just north of Telford and Wellington in Shropshire, which Loch set about draining with a will. Loch’s reputation in Shropshire does not appear to have been so contentious as it was in Scotland, and the landscape he created in the Wealdmoors is now level ploughland of peat interspersed with rectangular plantations of poplar.

In the Somerset Levels, the surviving nucleus of wetland commons was tackled between 1770 and 1800. The period opened with the usual resistance from the inhabitants, who dug an open grave for William Fairchild, the surveyor of King’s Sedgemoor, and announced ‘a reward of a hogshead of cider … to anyone who could catch him’.43 Nevertheless, by 1800 a commoner was speaking with regret of the times when the undrained wastes had given him pasture, where ‘he could turn out his cow and pony, feed his flock of geese and keep his pig’.

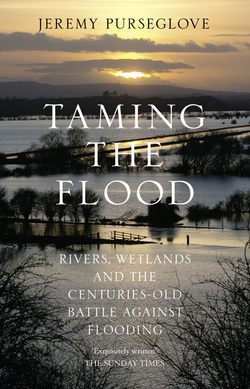

Moles, the bane of drainage men, gibbeted on a willow tree as described in John Clare’s poem ‘Remembrances’.

The Somerset Levels. The dwellers of the Levels successfully resisted the kind of large-scale drainage which transformed eastern England in the seventeenth century.