Читать книгу Taming the Flood: Rivers, Wetlands and the Centuries-Old Battle Against Flooding - Jeremy Purseglove - Страница 32

PHYSICAL DESTRUCTION FROM RIVER ENGINEERING

ОглавлениеThe real cost of river mismanagement can begin with engineering works on the watercourse itself. As many of the old river managers learned from first-hand experience of tinkering with their rivers, it is ultimately far more productive to work with a river than against it. It is the nature of rivers that they refuse to stay straight. ‘It’s always twisted,’ said a seasoned riverman of the Shropshire Rea, ‘and it always will.’ Cage a river in cement and iron, and it will struggle to break out like a wild beast. Major straightening of the Mississippi in the 1930s, largely for navigation purposes, is still creating problems for its present-day managers over hundreds of miles. Attempts to straighten out the Lang Lang river in Australia between 1920 and 1923 caused a series of cuts into the bank, which progressed rapidly upstream and destroyed seven bridges.4

But it is not necessary to look so far afield or so long ago for examples of rivers which have refused to obey the dictates of engineers. In 1864 the river Ystwyth in Wales was straightened to run parallel to a railway track. In 1969 it was back again on its wandering course, and was engineered cheaply back into line by dredging out the gravel shoals which were causing it to wander. However, this did not turn out to be such a cheap solution in the long run, since it set up conditions of even greater instability, necessitating repeated operations every two years.5 Major work on the river Taff and the river Usk in South Wales, carried out in the early 1980s, has precipitated extensive and unforeseen repair bills. Those who win money on the horses at Kirkby Lonsdale races in Cumbria can quickly sober up if they wander down from the racecourse to see how their rates have been spent on the adjacent reaches of the river Lune, where the recently cemented banks are dramatically caving in, and attempts at bank protection appear to have made matters worse.

The river Trannon is a fast Welsh mountain stream, which flows down towards the Severn in Powys. In 1978–9 a short reach near the village of Trefeglwys was given a thorough canalizing treatment. Trees were cleared from the banks, and raised flood-banks were built out of the dredged material alongside the stream course. Almost immediately it became clear that the river was kicking back at the abuse it was receiving. In the winter of 1979–80 the Trannon careered off on a course of its own. Fencing, which had been set well back from the bank, now dangled over the gulf created by the all-swallowing river. As more and more stone-filled gabions were built in to reduce the erosion which the scheme had set in train, it became apparent that Pandora’s box had been opened, and that what might have worked as a piece of traditional river canalization in the cohesive sediments found downstream had proved a recipe for disaster when applied in the unstable gravels of this upland brook. At one point, the original river bank, shored up by wire and stone, remained the only still point, actually down the centre of the fast-moving Trannon, so that it was a job to guess whether the buckling gabions had belonged originally to the left or to the right. Seven years later, remedial works were still being carried out; the raised flood-banks set far too close to the watercourse were being eroded away; the stability of the downstream bridge was threatened; and the real cost to the public purse of what was a relatively small scheme originally has yet to be clearly counted. In 1982 the Institute of Hydrology carried out trials on the Trannon, and in 1986 was able to come up with a number of constructive lessons to be learned from this sorry story. Relatively cheap methods of testing local ground conditions which have been researched by geomorphologists can act as useful warnings to engineers as to whether they are risking the kind of problems which now make the Trannon scheme, with hindsight, a questionable one to have undertaken in the first place.6

Working with nature is clearly practical, as well as ecologically sound. In 1985 dredgers were busily raking up gravel from the shoals in the river to put into more gabions for bank reinforcement beside the Trannon. As part of the normal processes of a river, the stones in these shoals are neatly sorted and graded by the flowing water into an overlapping fish-scale pattern known as ‘armouring’, which makes them relatively stable. By dredging up gravel, therefore, river managers were actually de-stabilizing the river bed, thereby contributing to the erosion which they were supposedly trying to prevent. Riverside trees, whose roots increase the tensional strength of the bank material, are the best protection against erosion, especially if they are well established and are properly maintained. They also reduce land loss, since it is estimated that channels with 50 per cent tree and shrub cover on both banks require only approximately half the width for a given volume of bankfull flood-water speeding through the channel, compared to treeless brooks which erode out into the adjacent fields.7 If trees are felled in the hope of gaining extra land, a river is likely to move out to take that land, and on certain types of river a great deal more besides. One has only to stand on the bridge over the Trannon at Trefeglwys and look upstream to see the stable narrow river coursing elegantly between its magnificent borders of ash and sycamore, and compare this with the immediate downstream reach, which wanders amidst a waste of gravel.fn4

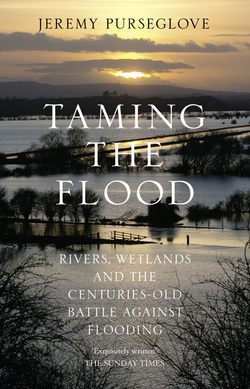

An engineered river moves out of control. After the trees had been removed, the stone and wire were set to reinforce the bank. The stream then split, turning the old bank into an island. River Trannon, Powys. © Malcolm Newson