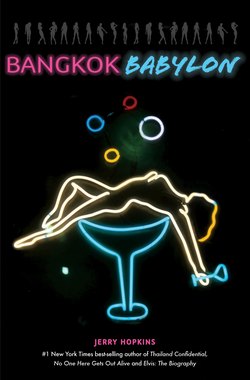

Читать книгу Bangkok Babylon - Jerry Hopkins - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Urban Guerilla Priest

ОглавлениеFather Joe Maier took a seat at the table across from me, and as I ordered two mugs of Heineken draft, he took a call on his cell phone. It was January 2, 2000, the start of the new millennium, and we'd met to celebrate numerous past failures and occasional victories and a future of more of the same. A moment later, he ended his call, abruptly stood, and said, “There's been a gas leak at the ice house. You want to come along?”

We ran to his car, and as he sped through the Bangkok night, driving as I'd never seen him drive before, he explained that the place that produced ice for many of Bangkok's drinks was near his AIDS hospice and two of his shelters for street kids.

“Tell me what you know about freon,” he said.

“I don't know much. What I remember from physics class is that it's an odorless, colorless gas that has no effect on humans, but according to more recent studies, it screws up the ozone layer. Why?”

He said that was what he was told was leaking into his neighborhood, the Klong Toey slum, the largest of some 1200 urban areas that were officially designated as slums in Bangkok. About a year earlier, Joe said, there'd been a fire in the ice house and it should've been shut down permanently, but the woman who owned it paid a visit to a local politician who paid a visit to the cops and nothing was done. That's the way troubles were handled in Bangkok.

We were still speeding through the streets, squealing as we hit the corners, bouncing into and out of pot holes. I laughed.

“What's so funny?”

“I had a thought. You know those movies where the cop's driving an unmarked car when he gets a call and he reaches out the window and puts one of those flashing lights on the roof? Where the light is stuck to the roof by a magnet and is plugged into the cigarette lighter? I just had an image of you doing that, except you have a flashing crucifix.”

He laughed as we slid around another corner and the rest of the way to the ice house we argued about what kind of noise should be coming out of the car when the crucifix was in place. We agreed it couldn't be a siren or anything that sounded like cops or an ambulance. I argued for Gregorian chants and Joe held out for “Ave Maria.”

At our destination, our joking stopped. “That's not freon, it's ammonia,” I said as we exited the car, “–and that could seriously kill somebody.”

All around us, life was proceeding as usual. At a food stall across the narrow street from the ice house people ignored the bad smell and spooned up bowls of noodle soup. How unusual, after all, was an offensive odor in a Bangkok slum?

Joe accessed the situation and we took off at a trot toward the Mercy Centre, where, after he was assured that everything was alright, he left me with a friend. Bangkok is one of those unusual cities where personal safety was pretty much assured everywhere and at all times, but Joe insisted that unless you were Thai, Klong Toey had not only bad smells, but also the whiff of danger for outsiders. As a longtime resident known in the neighborhood, he figured he was exempt from any such threat.

As I waited for Joe to return, I remembered how he'd come to Bangkok in 1967, straight from seminary in California, to say Mass to American soldiers fighting the war in Vietnam. His grandparents were homesteaders farming wheat in what was then called the Dakota Territory. His parents–German father, Irish mother–ran a whorehouse in Chicago for a while and after Joe was born, his dad became a fisherman on the West Coast, a ship's captain running supplies for the army to the Aleutian Islands during World War II, a truck driver in Washington state, a farmer back in South Dakota, a traveling salesman, a guitar-playing minstrel, a house painter, a womanizer, an absent father and a drunk.

Joe's younger sister and brother were born in the harsh Dakota winter and both times, at age ten and twelve, Joe drove the tractor, pulling the car behind him with his mom and dad in it until they reached the county highway, where they waited for a snowplow to clear a path into town, so that his siblings could be born in a hospital. He milked cows. Ran a threshing machine. Finally, the old man just sort of disappeared and when Joe went to catechism summer camp, classmates laughed at his clothing, one pair of high-top work shoes and two pairs of bib overalls.

Eventually, his parents divorced, and his mom and the kids settled in Washington state where she had a sister and found a job as a secretary; welfare took up the slack. Joe's mother was a strong woman, Joe said–manipulative, larger than life; “I had my first adult conversation with her when I was fifty-three.”

Starting in the seventh grade, Joe was shipped off to a Catholic seminary in California for six years, during which time he became the only Eagle Scout in the seminary. He was mercilessly teased, just as he was a target in the troop for being the only Catholic. He also suffered through a bout of polio that affected some minor muscles in his face and made his fingers unfit for continuing piano lessons, although he was still able to make a fist.

After a spiritual internship in Missouri, Joe was ordained and shipped off to another seminary in Wisconsin. This is where he earned his merit badge in rebellion, challenging seminary regulations and protesting the nascent Vietnam war. His superiors got their revenge. In 1967, as the war heated up, they sent him to the country next to it, Thailand. He was not pleased. And he vowed not to stay.

“I was an angry young man,” he recalled, “and the rest of the priests were glad to see the back of me.”

The sermons on the military bases stopped when he completed his Thai language classes and was posted in Loei near the Laos border, where he taught himself Lao, and then, after crossing into Laos, took his faith to the hilltribes; he once told me he thought he still could say Mass in Hmong. This is when he got to know all the classic characters–and killers–of the secret Laos war.

By war's end, Joe was back in Bangkok, where he took over the parish in the city's toughest slum, called the Slaughterhouse for the abattoir where three thousand pigs were killed every night. Most of the butchers were descended from Vietnamese Catholics who migrated to Thailand, because Buddhists were forbidden to kill and Muslims wouldn't go near pork. Fast food joints refused to deliver in this neighborhood, taxis wouldn't take you there after dark, and if you let it slip to a prospective employer that you lived there, you didn't get hired. Joe moved into a two-room shanty squat in the middle of the slum, slept on an old army cot, dressed himself out of the poor box, offered spiritual nourishment to the butchers and their families, and in 1972, started a kindergarten. This is where the accomplishments that followed began. From then on, Joe said, it was war, and the priest not only said Mass on the weekend, he became an urban guerilla.

When he heard a ten-year-old girl whose mother was a prostitute in a brothel was going to introduce the girl to the trade, Joe negotiated a price with the brothel owner to buy the girl, then put her in a school and a foster home. When a twelve-year-old slum girl was raped and a man was apprehended, it looked as if he'd walk after paying a bribe. Joe had four hundred slum women march on the police station, telling the cops to either guarantee they'd prosecute the sonofabitch or give him to the women for one hour, and if they didn't do one or the other, he'd be back the next day with the women and media. (The man was sentenced to seven years.) When Joe learned that some gangs were planning a move on a neighborhood and he noticed that the canine population was nil, he organized a posse and “borrowed” a dozen or so animals from another slum area to stand guard.

Perhaps he was most creative when there was a fire. They averaged about two a year, and Joe believed that it was important to rebuild immediately. A community meeting was held even as the embers cooled. The city had a program where homeowners– even if they were squatters living on land illegally–were entitled to more than $500 after a fire, and renters got about half of that. Joe said he'd advance the money needed to start construction on an adjacent piece of wasteland that very day, explaining that the longer they delayed, the harder it would be to claim the right to rebuild on or adjacent to the original slum site.

Joe's social workers told the people that after a fire, everything material was gone, except for the few items saved on the way out of the flames, so it was important to hold on to the social structure. That meant that if these people could continue to send their children to the same schools, if they could continue to take the same bus routes to their jobs, if they could continue to shop at the same slum stores, if they could continue to see the friends and relatives with whom they'd lived–often for generations–still in place as a community, their chances of survival were increased. And the psychological damage might be diminished.

At the meeting, they also were told that the new houses probably would be smaller than their old ones and that it would take a year, maybe two years, fighting through all the red tape before they could rebuild on their original sites. It would not be easy. At one such meeting I attended, a man said if rebuilding was illegal, maybe the police would arrest them. He was told that if anyone were arrested, everyone else in the neighborhood was to go to the police station and surrender, confessing identical guilt. Before they went, the mommies were to give the children as much to drink as possible and sticky candy to eat, so that when they got to the police station the smallest children would end up peeing on the floor and leaving their gummy handprints on policemen's trousers. The mommies were also told to have the children take their dogs, so they could pee on the floor as well.

Committees were formed. One to deal with the police and government. Another to distribute food and clothing that was coming in from the business sector and concerned citizens. A third to organize activities for the children. One more to visit the lumber yards the next day and find the cheapest nails and wood and corrugated roofing, all at Joe's expense, repayment due when the government honored its mandated compensation.

The fire meeting I attended was on Thursday afternoon. The lumber and so on was delivered by Friday night. Construction began right away. Daddies, mommies and children carried the boards and bags of cement. Tools were loaned by others in the slum. The nine-meter-long poles that would be used as corner posts for the new homes were too long to be carried down the twisting walkways from the highway, so the men waded across a swamp with the boards on their backs.

All night and through the next two days and nights the slum echoed with the sounds of hammers and saws. Every slum has its “slum carpenters”–men who have worked in construction or who have built their own homes in the past–and they told the others what to do. No one slept longer than a few hours, thanks in part to someone's having laced the drinking water with amphetamines.

The last family moved into the last house at 6:30 a.m. Monday, just as the sun came up and well before government offices came to life in an effort to keep the slum dwellers from rebuilding. The stench of the charred wood still hung in the air, along with the sweet smell of success.

In every war there are losses as well as victories and Joe's was no different. Pigs were not slaughtered on a monthly occurrence called Monks' Day, but on one of them, which also happened to be his birthday, Joe arrived at the Slaughterhouse in his white robes, coming from some public appearance. He stopped to lead the butchers and their families, who lived in shacks built on top of the killing pens, in saying the rosary. Nearby was a small group of men who'd decided to kill some pigs anyway, for the easy profit, and they ignored Joe when he asked them to stop for the twelve minutes that the prayers took. In response, the men splashed Joe with warm blood. He was shocked. He remembered bolting and then standing still, alone, for five minutes, then joining another group of men who customarily spent their evenings drinking and gossiping. Joe told them what happened and said he was going back to America.

Packing a small bag, he drove to the Holy Redeemer Church and, finding it locked up for the night, climbed a drainpipe in the back and went to sleep in one of the small bedrooms usually used by new or visiting priests. About three in the morning, he was awakened by a pounding on the church door. He pulled on some clothes and to his great surprise, he saw several of the Slaughterhouse men, drunk, who'd arrived in a pickup truck. “You can come home now,” one of them said. “We took care of the problem.” Joe was told that when the police arrived to arrest the men for violating Monks' Day, mysteriously they'd all had accidents and had broken arms and legs. Eleven were taken to the hospital and the owner of the firm that employed the men was taken to the police station and told it would cost him $2,000 if he wanted to go home.

Another time, when a young priest in the slum was threatened–he later became an archbishop–one of Joe's neighbors (now deceased) carved up the would-be assailant and fed him to the fish in the polluted canal that ran alongside the Slaughterhouse.

“It's war,” Joe said. “The slums never invited me. I walked in and said here I am, let the Klong Toey wars begin. It was total arrogance and bravado. I tend to overstate and over-emotionalize, but I'm right. We've never done anything legal, but we've always played it straight, we've never broken the rules of the street.” He paused and then talked about a bishop in Brazil who told him, “When I help the poor, they call me a saint, and when I teach the poor how to help themselves, they call me a communist.” Joe paused again and finished his small speech: “I'd rather be a communist.”

For twenty-five years, he was the only priest who visited Bangkok's meanest prisons. He also conducted Mass every Sunday for a quarter century at the prestigious Asian Institute of Technology, from which he also received, following a year's study, a degree in urban development. After a while, he incorporated his foundation (in the church's name, of course), and by 2003, he had built more than ten thousand slum houses of his own design and was riding herd on thirty-three schools with an enrolment of 4,500 kids and more than seventy thousand “graduates” who'd learned the basics of literacy (from teachers who were born in the same slums); five shelters for over two hundred orphaned, abandoned and abused children; the city's oldest AIDS hospice for fifty children and 150 adults; social workers on the street seven days a week; a legal attack team that represented two hundred kids in courts and police stations every month; a twenty-four-hour medical clinic, a credit union and women's advocacy group; and several self-help, skill-teaching programs that produced everything from candles to Christmas cards.

As I remembered all this, I stood near the compound that included the AIDS hospice, two of the shelters, the largest school and the foundation's offices, a $4-million fortress called the Mercy Centre, financed by an American businessman from Atlanta.

As I ruminated, Joe told me later, he arrived at the neighborhood police station, where for the next twenty minutes the portly, balding, sixty-year-old priest from South Dakota, whose mixed Irish and German blood boiled at thirty degrees Celsius, the average daily temperature in Bangkok, informed the cops who had the misfortune to be on duty that night precisely how they were fucking up. (His words.)

Why weren't any cops on the scene at the ice house? He wanted to know. Why didn't they have a loudspeaker announcing the danger from inhaling ammonia gas? Was anything being done about the leak? Did they know how harmful ammonia was? What was the plan if someone got sick?

There were many cops who welcomed Joe, and there were others who liked to get rid of him as quickly as possible, even if they had to capitulate a little, so in a short time, it was agreed that the police would dispatch someone to the ice house with one of those battery-operated megaphones and search for any injured or ill, in the plant and in the immediate neighborhood, and if any were found, to take them to the hospital.

After collecting me, Joe and I hot-footed it back to the ice house, where he confronted the owner, who was sitting nonchalantly on the loading dock. The smell of ammonia was still noxious in the air.

Now, Joe gave her holy hell, causing her to lose a bit of her face as there were several others present, but extracting a promise to pay for any possible hospital costs.

With the cops arriving and the woman moving to greet them, Joe and I returned to his car. “This,” he said as we walked, “is how journalists and priests get killed.”

I laughed again. “Happy New Year to you, too, Joe.”