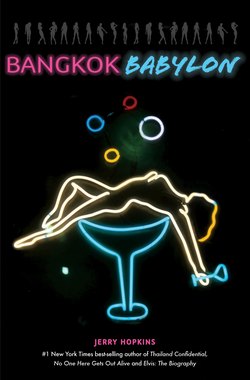

Читать книгу Bangkok Babylon - Jerry Hopkins - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Spy, Fixer, Raconteur

ОглавлениеThe man's shape was formed by years of beer consumed sitting on the stool at the end the Madrid Bar in Patpong. When other regulars entered, they said, “How are you?” “Not bad,” he replied, “for a man with no liver.” The Bangkok Post was opened on the bar in front of him, one hand held a mug of Klausthaler, the non-alcoholic beer that his doctor prescribed, the other was fitted to a bar-girl's left buttock. It was one of the smallest bars in what's usually called Bangkok's “most notorious red-light district,” and it was almost noon.

An old friend slid onto the stool next to Jack Shirley, the old CIA spook who owned a piece of the place and a legend left over from the “secret” war in Laos. Jack folded the paper, gave the girl a final squeeze, and started to reminisce. The stories fell onto the bar top like handguns dumped from a sack.

There was the time he was drinking in another bar when a former Russian KGB agent named Boris challenged him to a pushup contest. The war in Laos was long over and Jack looked a bit of a mess, but he hit the floor and pumped a hundred. As soon as the Russian executed his 101st, Jack kicked him in the head hard enough to knock him senseless. A week later, when Jack was drinking there again, Boris joined him, still six colors of the rainbow from the kick. Boris greeted Jack with a grin and merely said, “You got me that time.”

This was Jack Shirley at peace. At war for the CIA and when he was farmed out to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, he didn't kick, he killed. By his own admission, he was a hit man, a “journeyman killer” who claimed to have “zapped” an even dozen bad guys for his government. There was the time he was sent to Hong Kong Island to make a heroin buy, and on the way out of the building, he “accidentally” bumped into another spook, transferring the smack so that when, as expected, he stepped off the Star Ferry onto Kowloon and was jumped by the cops, he was clean and had to be let go. The dealer had set him up and bribed the cops so he'd get his heroin back.

A couple of months later, Jack set up another deal with the same dealer, this time a “big sell” that was to take place in a luxury house in Hua Hin, two hours south of Bangkok. His old friend Tony Poe was inside the house and Jack was outside in the bushes. A car pulled up with two occupants, the dealer and his driver/bodyguard. The dealer went inside. Jack strolled up to the car and zapped the driver, but before he could get to the house, he heard a gunshot. As Jack burst in, there was Tony holding a pistol and grinning over the dealer's corpse. Jack told friends at the bar he was pissed; he'd wanted to slap the dealer around first, have a go at him for trying to get him busted in Hong Kong.

Then there was the time in Laos when he was chased by the North Vietnamese for five days around torturous mountain trails. He and Tony and some other top CIA para-military officers had divided the country into five parts in 1961, back when any foreign presence there was prohibited by the Geneva Accords that followed Vietnam's defeat of the French. They then organized the Hmong hilltribe into an army to fight the Communist Laotian Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese Army, who crossed the border into Laos at the head of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, then being used to funnel troops and supplies from North to South Vietnam. Jack got the village headmen together and told them he'd supply all the guns and ammo they needed. They wanted to know how much it would cost. He said nothing and they laughed. Jack made a call on his walkie-talkie and the next day crates of weaponry fell from the sky. That's when the Hmong pledged their allegiance, and the North Vietnamese started chasing him.

Another time, he and Tony identified an avowed neutral Lao general who was really working for the communists, so they set up his assassination. They knew which whorehouse he frequented and bribed his favorite girl to give them the time and room number for his next visit. When the general entered the brothel, Jack and Tony flipped a coin to see who got to zap the guy. Tony won. After screwing in silencers, Tony went through the front door, Jack in the back, and Jack reached the girl's door first. He waited for Tony, but the designated killer was delayed for some reason. Worse, the general was a known premature ejaculator and Jack could tell from the girl's voice–remember that she was being paid by Jack and Tony–that the general was getting dressed. Jack couldn't wait any longer: he kicked in the door and did his patriotic duty.

He said he got his first taste for killing as a boy growing up in Maine, where he “bagged” more deer than he could remember. Later, as one of the CIA 's earliest recruits, he trained in the same class with Poe at Camp Peary, before the present offices in Langley, Virginia, were built. One of Jack's first assignments was to accompany small airplanes that the U.S. government gave to the Thai government to set up what became the Border Patrol Police. Jack stayed on to train the flying cops–becoming the first and perhaps only foreigner to wear a Thai police uniform–and was given the rank of captain. He also inaugurated the police parachute training school at Hua Hin–one of the reasons so many cops on the street today wear parachute badges on their shirts– and was instrumental in setting up camps in the North and Northeast along the Laos border which became crucial during the war in Laos and for drug interdiction.

In 1970, Jack returned to the States for an official “retirement” and Tony took his place; once merely competitive partners, by now they were virulent antagonists, rarely speaking at fewer than eighty decibels, equal to a gunshot. As the war wound down–a truce was signed in Paris in 1973 and the communists took Laos along with Vietnam two years later–Jack returned to Thailand as a “civilian” police advisor, settling in Hua Hin and running the paratroop school. He also began investing, along with other ex- CIA spooks, in the new bars that were opening to accommodate the “sex tourists” that were replacing the GIs on R&R.

For many years, Jack and his fellow spies and onetime professional warriors hung their beer bellies on the bar at Lucy's Tiger Den, a joint on Suriwong Road that had a large banner that said it was the designated watering hole for members of China Post One of the American Legion Operating in Exile Out of Shanghai, a holdover from General Chennault's Flying Tigers of World War II. When Lucy's closed, Jack moved to the Madrid Bar around the corner in Patpong. This is where we met, in 1995, when I fortuitously sat next to him. When we introduced ourselves and I said I was a writer and he asked what I was working on and I said a story about how Hollywood movies got made in Thailand, he said, “So that's why you're here?”

“No,” I said, “I came for the bean soup and corn bread.”

“You don't know who I am?” I said I did not and he laughed so hard he knocked over his beer. (This was in the pre-Klausthaler days when he drank Singha.) For the next two hours, he talked, skipping over the entire war–and the stories I'd hear later–to tell me how he earned thousands of dollars from Hollywood producers and never left his stool at the Madrid, using a cell phone to call his old cop friends, many of whom were now generals, to get permission to bend if not totally ignore the law in the interest of getting the movies made.

There was the time, he said, when Jean-Claude Van Damme wanted to blow up and sink a boat in the Chao Phrya River. That was a tricky one, he said, because he had to get approval from the cops on both sides of the river and get the maritime police to stop traffic on the river itself. After some special “fees” were paid, the boat was exploded and sunk. Another time, Oliver Stone wanted to shut down traffic on a main thoroughfare during rush hour. Occasionally, someone else needed a bar- or drug-related infraction overlooked.

Jack got his start as a “fixer” in 1977, when a Hollywood producer named Bob Rosen hired him to find locations and “grease the reels” for a Steve McQueen film. The story was based on a real one dating to World War II, when America's famed Flying Tigers, were being out-flown and out-gunned by Japan's newest contribution to aerial warfare, the Zero; McQueen and his Burmese sidekick (to be played by Charles Bronson) were to steal one of the enemy planes. John Frankenheimer was to direct.

The Deerhunter had been filmed in Thailand recently and the producers had been ripped off. Bob says now that it was because the film company didn't have anyone working on the inside. Jack took Bob to the Laos border, considered a prime site for filming, where he met top officers of the Border Patrol Police, who said they'd heard McQueen was fat, a side effect to cancer treatment that Bob didn't know anything about. Jack then took Frankenheimer to meet the prime minister, who gave the director permission to use the former U.S. air base in U-tapao, from which much of the bombing of Vietnam had been staged. Then McQueen revealed that he did have cancer and the part was offered to Clint Eastwood, who liked the script but didn't want to go to Thailand, so the movie was never made.

Impressed by Jack's access that went all the way up to the prime minister's office, Rosen returned to Hollywood and when he signed on to produce Prophesy, a horror movie, and he needed a chief of security, he invited Jack “to come and do something stupid.” His job: keep anyone outside the camera crew from seeing the monster.

Bob called Jack again when he made The Island, Peter Benchley's follow-up to Jaws. This film, which was shot in Antigua, told the story of a band of modern pirates–the descendants of real pirates from three-hundred years before–who preyed on yachts. Centuries of inbreeding had resulted in a band of “freaks,” so only the truly deranged and handicapped were cast. Jack's job was to keep them in line.

Ironically, he also was charged with keeping them sober. By then, Jack was methodically drinking himself to death. Rosen said he finally talked Jack into coming to the States to dry out. For three months, Jack lived with the Rosen family in Seattle, experiencing what Bob called an “amazing” recovery.

Back in Bangkok, he met a young Thai girl named Pen–in time, he would marry her–and for a while he dutifully drank the Klausthaler he had learned to hate. In time, he returned to the real thing and Pen accompanied him back to Seattle to dry out again. “His liver was pretty shot,” Bob Rosen said, “but, again, when he stopped drinking, he got better.” Bob said he also tried at this time to get Jack to make peace with Tony Poe, but when he called Tony in San Francisco, it wasn't long before they were threatening to kill one another.

Rosen was so entranced by Jack, he hired a screenwriter to write a treatment for a film based on his life. The way Bob tells the story, John Frankenheimer showed some interest for a while and so did novelist Joseph Heller, but at the time the project was presented, the CIA was “all short haircuts and James Bond, and to do Jack's story right, it had to be about a guy who drank too much and fucked up. In other words, a human.” Other friends say Jack didn't like the treatment because Tony Poe played a role in the story that diminished his.

Unlike Tony–whose alcohol-fueled violence eventually led the Thai government to deport him (in 1991)–Jack was an amiable drunk. He enjoyed meeting new people, laughed a lot, and always deferred to anyone of superior rank or standing. When William Colby, the former head of the CIA, was in Bangkok and addressed the Foreign Correspondents Club, one of Jack's friends– a former university professor–tore into Colby verbally, attacking some of his tactics and policies. Next day, when the friend told Jack what he'd done, Jack was aghast, accusing his friend of a breach of authority and propriety.

For the media, however, he held only the highest disdain, blaming them for “losing the war at home” and for calling America's efforts in Laos a failure. “Tell me,” Jack asked, “how was a handful of CIA with a bunch of Air America pilots going to win against the goddamned Vietnamese army? We weren't the U.S. Army! We were a supportive side action to the main war. We kept tens of thousands of Vietnamese soldiers tied down in Laos, damaging the enemy's effectiveness in South Vietnam. We cut into their movement of supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail and we kept the commies from moving into Thailand. We never lost Laos by a military action. It was signed away by treaty after the fall of Vietnam!”

That more bombs were dropped on Laos than on Nazi Germany, and that the CIA left behind a country full of bomb craters, amputees on crutches and antipersonnel bomblets that still kill hundreds every year, was beside the point. Jack believed the cause was just. His hands were untainted, his conscience clear.

“Some people don't realize the CIA was created to do the things the country couldn't do out in the open. Absolutely nothing we did was legal,” he said. “I don't feel bad or any remorse whatsoever about zapping those guys. It didn't feel any different than shooting all those deer.”

As the drinking continued, in 2002, Pen thought a move two hours away to Pattaya might help, by distancing him from his drinking buddies. It didn't even slow him down. Nor did a big sign that was hung in his favorite bar: “ JACK 1, COMMUNISTS 0... SINGHA 1, JACK 0.” Now he visited Bangkok only to see his doctor. Yet, his health continued to fail. He started talking about cremation, calling it “my barbecue.”

The “barbecue” was held in Pattaya in April 2003. Nearly two hundred friends came to the send-off, including an emissary sent by Thailand's royal family, bearing the flame to light Jack's pyre in gratitude for his work on Thailand's behalf. He was seventy-six.