Читать книгу Spectacle of Empire - Jerry Wasserman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Getting to Know Neptune

ОглавлениеI visited Port Royal for the first time in May 2004 on a side-trip from Halifax, Nova Scotia, where my wife, Susan, and I were attending a conference on Canadian theatre. Standing on the shoreline of the Annapolis Basin in front of the small structure that is the restored Port Royal fort, staring out into the sheltered waters, I tried to envision exactly where the ship carrying the Sieur de Poutrincourt and Samuel de Champlain would have been anchored that November day four centuries ago; how Neptune, his Tritons, and the pretend-Indians in their canoes would have arranged themselves in relation to the larger vessel; and how anyone on the shore could possibly have heard any of the dialogue Marc Lescarbot wrote for the occasion. The spectacle was easier to imagine: the costumes, props, and gestures, the song and cannon fire. Thankfully, the rebuilt fort itself, the Habitation, is largely free of touristy tackiness (see fig. 1). In fact, though Port Royal is a Canadian National Historic Site, the Habitation was difficult to find – the signage in Annapolis Royal proper, about ten kilometres distant, where the former British fortress is very well preserved and promoted, was practically non-existent. Arriving there, we found a modest structure with few tourists, a ticket booth but no gift shop – we couldn’t even buy a postcard on site – and only a single bilingual guide, in period costume, who gladly took us through the roughly furnished rooms, explaining who lived where and did what. When I asked him if he knew about the play, he responded by reciting Neptune’s entire opening speech in French.

It was the kind of pilgrimage I had made before – finally standing in the place where it had all begun, the place where the plays and playwrights and theatre history I was teaching and writing about had actually originated. I had had similar experiences at Epidaurus and Stratford-upon-Avon, at the Comédie-Française, London’s Royal Court, and Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto. Growing up in New York, I had always had a feel for a certain kind of theatre. I knew viscerally what “Broadway” meant. “Off-Broadway” and “off off” became as familiar as drinking beer while I was going to college in the 1960s. But when I went on to graduate school, then started teaching, I realized that I felt fraudulent about a lot of what was supposedly “in my field.” I felt uncomfortable claiming expertise in regard to material that arose out of particular geographies I had never experienced first-hand. Finally getting to those places, I have found, makes a big psychological difference.

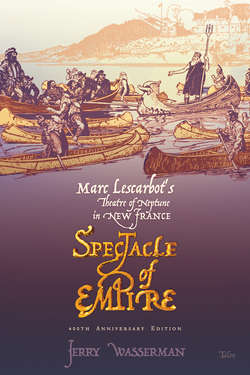

Fig. 1. Exterior view of the reconstructed Port Royal Habitation. Courtesy of Wikipedia. Photograph by Danielle Langlois.

As a latecomer to Canadian theatre, working in it as an actor and learning about it on the job as it became more and more my central academic focus in the 1970s and ’80s, I was first convinced that nothing prior to 1967 really mattered much. That was when a homegrown, fully professionalized theatre had finally emerged in Canada with plays, playwrights, and a performance history sufficient to delineate some kind of canon. It was only in the mid-1990s, when I reluctantly inherited and began to teach a course in pre-1967 Canadian theatre history at the University of British Columbia, that I started to see the error of my ways. Canadian theatre, it turned out, has a history as full of incident, human interest, theatrical event, folly, heroism, and humour as any other nation’s. As a hyphenated Ameri-Canadian, I developed a particular fascination with the long colonial struggle of Canada’s pioneer theatre artists and entrepreneurs to carve out a newly defined, hybrid “Canadian” theatrical space amid the conflicting territories already occupied by British and American theatrical, political, and economic interests, while also negotiating across the nation’s two internal solitudes: the French-English divide, and the even greater gap between First Nations and the Euro-Canadian settler-invader culture that came to dominate the northern half of the continent.

Marc Lescarbot’s The Theatre of Neptune in New France was an exciting discovery for me. It was a starting point, an originary moment. We could talk in class about Native American and Native Canadian ritual performance, examine photographic reconstructions and artifacts, and even watch a video of authentic-looking (but staged) performances by Kwakwaka’wakw dancers in full regalia in Edward Curtis’s 1914 film In the Land of the Headhunters. But when Eugene and Renate Benson published their new English translation of The Theatre of Neptune in 1982, and Anton Wagner reprinted it in his marvelous four-volume anthology, Canada’s Lost Plays, we had an actual first script to read and study. Although recording a one-time-only event that had no apparent influence on the subsequent development of theatre in North America, The Theatre of Neptune was paradigmatic of a kind of performance that was more than just art or entertainment, though it was those things, too. It engaged political and cultural issues that were specific to North American colonial history but that remain current. It was exotic – a strange theatrical hybrid staged in boats on coastal waters – but it seemed to me also familiar somehow, connected to other plays I had read about and studied, and to the kinds of site-specific performances I was increasingly seeing in Vancouver. It adapted old world forms to new world circumstances, not unlike a much later landmark in Canadian theatre history, the opening of the Stratford Festival (see Wasserman 9). And it was really old. Who knew that we had a theatre history on our own soil that went back as far as Shakespeare’s time? I found my students first bemused, then thrilled by the notion that they could trace the pedigree of the enterprise into which they were entering all the way back to 1606. It became the hook that snared them, and helped snare me.

Through it I discovered Lescarbot’s History of New France and rediscovered Champlain’s Voyages, a book I had known about since high school but hadn’t looked at since then. But soon the Bensons’ translation and Canada’s Lost Plays went out of print. That was when I found that there had been earlier translations, including one (also out of print) by a remarkable American woman, Harriette Taber Richardson, who, it turned out, had been instrumental in arranging for the historical reconstruction of the fort which housed the men who wrote, designed, and performed the play. That place, in the same country but on the other side of the continent from where I lived, suddenly started becoming real to me. Then one day I realized that the four hundredth anniversary of the performance of The Theatre of Neptune in New France would soon be upon us. My brainstorm was to get the play back into print by November 2006 in an edition that would include the original French text, two of the English translations, each offering different kinds of valuable insights, and another dramatic work, in English, by a very well known playwright, contemporary with The Theatre of Neptune and with parallels to its art and politics that could help illuminate both texts. And I would contextualize it all, critically and historically, providing in Joseph Roach’s term a “genealogy” of its performance (25–28), expanding on some of the excellent research previously published on these lesser-known forms: the nautical masque, the royal entry.

I owe great thanks to my publisher, Karl Siegler of Talonbooks, who not only agreed to my proposal but leapt at it with an enthusiasm that has inspired me. Thanks to Davinia Yip who kept the whip to me and shepherded this into print with her usual editorial precision and acuity. Thanks to my colleague Tony Dawson for his sharp critical eye and help, especially with Ben Jonson’s arcane language. I’m grateful also to Eugene Benson, Denis Salter, and Ellen Mackay for their willingness to share ideas about the project. To Sue, for her patience and love. To the University of British Columbia’s libraries and librarians for their extraordinary resources. To a host of international libraries and museums for their generosity in providing us with illustrations: Bibliotèque municipale de Rouen; Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth; Library and Archives Canada; Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp; Pierpont Morgan Library, New York; Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champagne. To Dominique Yupangco for her help with electronic images. And to my colleagues in the Association for Canadian Theatre Research and the students of UBC’s Theatre 325 for always pushing me to get it right.

I dedicate this book to Patrick O’Neill. Enormously knowledgeable and generous, he knew more about the history of theatre in the Maritime provinces than I could ever learn in two lifetimes. Sadly, he didn’t live to see this anniversary.

Jerry Wasserman

University of British Columbia