Читать книгу Spectacle of Empire - Jerry Wasserman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

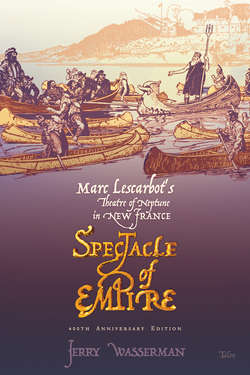

INTRODUCTION Marc Lescarbot and the Spectacle of Empire

ОглавлениеIn November 1606, a tiny band of Frenchmen welcomed a small sailing ship into the sheltered waters of the North Atlantic harbour they had christened Port-Royal, in the land their king called La Cadie (a common aboriginal word for “place” [“Champlain Anniversary”]), later to become l’Acadie or Acadia. Aboard skiffs or canoes out on the water, a dozen of the men – some preparing to spend a third brutal winter in this distant outpost of France in the new world – honoured their returning countrymen by performing a play that, in an oblique way, would have reminded them of home. It enacted welcome and thanksgiving in an elaborate, small-scale spectacle of wishful imperial triumphalism. Its shipboard audience consisted of the colony’s leader, Jean Biencourt, Sieur de Poutrincourt; the expedition’s geographer/ chronicler, Samuel de Champlain; and the ship’s captain and crew. On shore, outside their fortified living quarters, others gathered: some to participate in the performance, some to help provide its special effects, the rest comprising a second important audience of colonists and local Mi’kmaq people, including their chief, Membertou.

Ritual and ceremonial dramas of First Peoples like the Mi’kmaq, various paratheatrical activities among early Viking and European explorers, and documented but unpublished performances by sixteenth-century Spaniards in Florida and New Mexico all jostle for the designation of “first North American play.” One of the primary candidates for the honour has to be Le Théâtre de Neptune en la Nouvelle-France, written by lawyer, historian, and poet Marc Lescarbot in that tiny, short-lived French colony of Port Royal – the future Lower Granville, Nova Scotia – where it was performed on 14 November 1606 “on the waves,” according to Lescarbot, and along the shore of what today is called the Annapolis Basin. Unlike its competitors, the play was published and has survived as a script and literary artifact as well as a carefully documented performance. A rich store of theatrical, historical, and political detail, The Theatre of Neptune in New France vividly illustrates homo ludens, the human imperative to play, at a crossroads of art and ideology. It provides an unparalleled glimpse into the lost world of early seventeenth century North America, co-existing as a dense archeological site of early modern theatre history, a window into colonial North American social history and ethnography, and a snapshot of European strategies for imperial conquest.

As a living colonial artifact in a postcolonial age, the play still has the power to engage – and enrage. In response to a Nova Scotia theatre company’s plans to celebrate the historical milestone of Neptune’s four hundredth anniversary by re-enacting it on site on that date, Montreal’s Optative Theatrical Laboratories developed a project called Sinking Neptune to counter such celebrations. Presenting it as a work-in-progress, first at the Anarchist Theatre Festival and then at the inFRINGEment Festival in Montreal during the spring of 2006, Optative characterized The Theatre of Neptune as “an extremely racist play . . . designed to subjugate First Nations through the appropriation of their identities, collective voices and lands.” Through “masquerade and role appropriation, the play attempts to re-frame First Nation cultures into an exploitative Euro-centric social reality, and recast aboriginal peoples as subordinates” (King 5–7). For two years leading up to the anniversary, the company invited “political activists, theatre educators, culture-jammers” and others to help create a subversive, deconstructive counter-performance, “building a critical mass of cultural resistance to the play and re-enactment” (54). As we go to press in September of 2006, the Sinking Neptune project remains on track. But ironically, the re-enactment it was to confront in November has had to be cancelled for lack of Canada Council funding. What a quintessentially Canadian scenario. In any event these controversies indicate that after four hundred years The Theatre of Neptune remains a living, breathing dramatic enterprise, not just a theatrical museum piece. (See figs. 2 & 3.)

The Theatre of Neptune in New France was by no means the earliest Euro-American theatrical event. The Cambridge History of American Theatre lists four performances on its North American timeline preceding Lescarbot’s play (Wilmeth and Bigsby 22–23). Spanish comedias were played in Florida in 1567 and Cuba in 1590. In 1598, just north of the Rio Grande in presentday New Mexico, Spanish soldiers performed an original comedy written by one of their officers in celebration of their conquests – “the first documented play written in the New World,” though neither the script nor its title has survived (Davis 217). As well, various paratheatrical activities – ludi, or diversions, including musical ceremonies – may have taken place as early as 1000 A.D. among the Vikings who settled in Newfoundland, and on board the ships that took Jacques Cartier to Hochelaga (Montreal) in 1535 and Martin Frobisher farther north in 1576 (Gardner 1982, 7, 114–32). David Gardner argues that the first Canadian theatrical performance may have occurred as a “kind of folkloric prototheatre” in the form of mumming during Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s voyage to Newfoundland, either on board his ship Delight or on shore in St. John’s harbour in August 1583, where Gilbert “took possession of Newfoundland” for the English queen in a formal ceremony. Gardner makes his case based on first-hand reports that musicians accompanied the expedition along with such “toyes as Morris dancers, Hobby Horsse, and Maylike conceits to delight the Savage people” (Gardner 1983, 227).

Fig. 2. Charles W. Jefferys’s drawing for The Theatre of Neptune in New France, published in his popular Picture Gallery of Canadian History (1942). This has become the standard scenario by which to imagine the staging of the play. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada (C-106968).

Fig. 3. Optative Theatrical Laboratories’ poster for their Sinking Neptune project plays on Jefferys’s popular drawing. Courtesy of Donovan King.

But The Theatre of Neptune is certainly the first theatrical script to have been written and produced in what would become Canada. Its 1609 publication also represents a literary landmark of early Americana, marking the beginning of American literature in the Harris Collection of American Poetry and Plays in Brown University’s John Hay Library (“Early American Literature”). We have an account of the production from the playwright himself; a brief eye-witness confirmation of Lescarbot’s gaillardise (translated as “jollity” or “jovial spectacle”) by Samuel de Champlain, published in Champlain’s 1613 Voyages (see fig. 4); and an extant script with detailed production commentary (though how accurate it may be, we cannot know) preserved by Lescarbot in an appendix to his popular Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, published in Paris in 1609 and reprinted four times by 1618. Written by a member of the community and performed on site by soldiers, sailors, and artisans of the garrison, the play tells us a good deal about the life of that early North American settlement and the intrinsic importance of theatre to its survival.

Fig. 4. Title page of Champlain’s Voyages. Published in Paris in 1613, it included Champlain’s version of many of the same people and events Lescarbot described in his 1609 Histoire de la Nouvelle-France.

This first published play written and performed in North America represents, in Richard Schechner’s terms, a movement back and forth across the continuum of ritual and theatre, a braiding of entertainment and efficacy (performance enacted to effect transformations) no less organic than that of the dramatic ceremonials created and performed by the land’s original inhabitants. The Theatre of Neptune was performance intended to divert and entertain as well as to create, reinforce, and ensure the present and future well-being of its participants: performance that, in Schechner’s words, “makes happen what it celebrates” (128). “[W]hen efficacy and entertainment are both present in equal degrees – theater flourishes,” he argues, citing as an example the Elizabethan era coterminous with Lescarbot’s work (134). Although The Theatre of Neptune was a one-time-only event, it retains a theatrical potency that can be fully understood only by looking at the historical moment of the play and the material conditions of its performance in its original contexts.

In November 1606, Port Royal was the only European settlement in the Americas north of Florida. The French had continued fishing off Newfoundland and trading for furs along the St. Lawrence River after Jacques Cartier and the Sieur de Roberval abandoned their colony at Québec in 1543. But not until after 1598, when the Edict of Nantes and the Treaty of Vervins ended long-standing religious and civil conflicts and the war between France and Spain, did France try again to put down roots in its new world territories. In 1604 Pierre du Gua, Sieur de Monts received a charter from King Henri IV to explore and colonize the lands of La Cadie from latitude 40° to 46° (stretching from approximately present-day Philadelphia north to Prince Edward Island), and to convert the natives therein, in exchange for a monopoly of the fur trade. Accompanied by Champlain, who had helped map the St. Lawrence region the previous year, the 1604 expedition established its base camp on a small island that de Monts christened Ile Sainte-Croix. It sat along the north shore of la Baie Française (the Bay of Fundy), where the future state of Maine would meet the future province of New Brunswick. After a terrible winter during which fifty-five of the seventy-nine male colonists contracted scurvy, thirty-five of them dying of it (Champlain 304), de Monts moved the settlement to a more sheltered spot across the bay in 1605, on the southern shore of a peninsula near the mouth of what is now the Annapolis River in Nova Scotia. He named the harbour Port-Royal and constructed a small fort, the Habitation. De Monts then returned to France. (See fig. 5.)

In the spring of 1606 Jean de Biencourt, Sieur de Poutrincourt, who had accompanied de Monts on the first voyage, set sail again from France on the frigate Jonas to take charge of the Port Royal colony which de Monts had ceded to him. On board was another Renaissance man, the Parisian humanist lawyer Marc Lescarbot, called by his first American biographer “the French Hakluyt” (see Biggar). In his History of New France Lescarbot explained that he was desirous “to explore the district with my own eyes” and, somewhat mysteriously, “to flee an evil world” (II:286–87). Born sometime around 1570 in Vervins, northeast of Paris, where the historic treaty would be signed, Lescarbot received a rich classical education while studying law in Paris and Toulouse. Called to the bar in 1599, he had distinguished himself with Latin speeches thanking the Florentine Cardinal de Medici for his success in brokering the treaty negotiations between France and Spain at Vervins, and with his translations of two Latin ecclesiastical texts (Thierry 53–54, 74, 84). Soured by an “injustice” done to him in court by certain judges in favour of a “personage d’eminente qualité,” possibly a senior bishop – or perhaps just generally disgusted with what he considered a corrupted civilization – Lescarbot accepted an invitation from Poutrincourt, for whom he had done some legal work, to accompany him to the new world in 1606 (Thierry 2001, 100; Emont 58–62; see also Baudry). He remained there for a little more than a year, returning to the evil old world in the fall of 1607 and recounting his experiences in The History of New France. In it he also detailed the exploratory voyages of Verrazano, Cartier, Poutrincourt, and others; told the history of the St. Croix Island and Port Royal settlements; described at length the aboriginal inhabitants of that northerly environment; and appended a collection of poems, Les Muses de la Nouvelle-France, which included the versified Théâtre de Neptune, the only play he ever wrote. (See fig. 6.)

Fig. 5. Champlain’s map of Port Royal with the Habitation at the centre, published in his 1613 Voyages.

Fig. 6. Title page of Lescarbot’s Les Muses de la Nouvelle-France.

Lescarbot departed Port Royal for France in 1607, along with all his compatriots, only because the settlement was abandoned when de Monts’s fur trade monopoly was suddenly terminated by Henri IV. Champlain would return to New France the following year and re-establish, this time permanently, the settlement of Québec. Meanwhile, left in the care of the Mi’kmaq chief Membertou, the Port Royal Habitation was briefly reoccupied by Poutrincourt in 1610 and finally destroyed in 1613 by a British expedition from Virginia. Over the next century the area passed back and forth between the French and English in a series of military campaigns and political manoeuvres, with both the Mi’kmaq and French Acadian inhabitants increasingly marginalized, until the English took permanent control in 1710 and gave the garrison and community its present designation, Annapolis Royal. After five printings of his popular Histoire and a further career as lawyer, poet, historian, and sometime diplomat, Lescarbot died in France in 1641.

The occasion for the play was the return of Poutrincourt and Champlain from a voyage they had taken down the coast as far south as modern-day Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, in the late summer and fall of 1606. They had sailed in search of yet another site for a colony with “a suitable harbour in a good climate,” Poutrincourt having deemed the health benefits of Port Royal’s locale and weather no better than those of St. Croix Island (History II:318). The winter of 1605–06, although milder than their first, had still left twelve of the forty-five Port Royal colonists dead of scurvy (Champlain 375–76). Poutrincourt put Lescarbot in charge of Port Royal while he was gone, enjoining him “to keep an eye on the place, and to keep the peace among those who remained” (History II:319).

Lescarbot tackled his new responsibilities with relish. Unlike Poutrincourt, he saw Port Royal as a kind of paradise, a “spot more pleasant than any other in the world.” He lavished praise on its hills, meadows, and streams, its abundant river, and its beautiful harbour with “two most fair and goodly islands” (II:234). A recent biographer describes Lescarbot as a new Adam in a new Eden (Thierry 2001, 118). The citified lawyer expressed his delight “in digging and tilling my gardens, fencing them in against the gluttony of the swine, making terraces, preparing straight alleys, building store-houses, sowing wheat, rye, barley, oats, beans, peas, garden plants, and watering them, so great a desire had I to know the soil by personal experience” (History II:266). In addition to its agricultural activities Lescarbot oversaw the settlement’s other business, including hunting, gathering shellfish, digging drainage ditches around the Habitation, making charcoal for baking, and bartering bread for fish and game with the local Mi’kmaq people, whom the French called Souriquois (II:319–20). The settlement’s priest having died earlier that year, Lescarbot even preached on Sundays. “Nor was my labour without fruit,” he mildly boasts, “many bearing me witness that never had they heard such good exposition of Divine things” (II:267).

Meanwhile, the History retrospectively describes the “many perils” of Poutrincourt and his crew’s exploratory voyage as reported to Lescarbot and recounted first-hand by Champlain in his Voyages. Their misadventures among the warlike Armouchiquois as they sailed along the coast of the future Maine, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts left significant French and Native fatalities in their wake (see fig. 7). Unable to locate a site offering a milder climate, functional harbour, and more hospitable Natives, they set sail for the return voyage to Port Royal only to find themselves in heavy weather with a broken rudder. Just two days before their arrival they had an accident which they feared might sink their eighteen-ton barque. Even “at the entrance to Port Royal,” Champlain reports, “we were almost lost upon a point” (438). So it must have been as great a relief for the Poutrincourt expedition finally to reach safe harbour as it was for those left behind in the Habitation to see its return. (See fig. 8.)

Fig. 7. Champlain’s graphic illustration of the battles between Poutrincourt’s men and the local Nauset people at Port Fortuné – “Misfortune harbor, so named by us on account of the misfortune which happened to us there” (Champlain 423) – on 14–16 October 1606. The site is present-day Stage Harbour, near Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

With the colony’s leader gone ten weeks, no sign of help from France, and winter fast approaching, the remaining inhabitants of Port Royal had grown seriously anxious and even mutinous, Lescarbot suggests. He writes of the joy and thanksgiving with which they greeted Poutrincourt’s safe deliverance, and the celebratory performance they contrived to mark it:

After many perils, which I shall not compare to those of Ulysses or of Aeneas, lest I stain our holy voyages amid such impurity, M. de Poutrincourt reached Port Royal on November 14th, where we received him joyously and with a ceremony (une solennité) absolutely new on that side of the ocean. For about the time we were expecting his return, whereof we had great desire, the more so that if evil had come upon him we had been in danger of a mutiny (de la confusion), I bethought me to go out to meet him with some jovial spectacle (quelque gaillardise), and so we did. And since it was written in French rhymes, made hastily, I have placed it among the Muses of New France, under the title of “Neptune’s Theatre,” to which I refer the reader. (II:340–41, 566–67)

Fig. 8. Champlain’s drawing of the Port Royal Habitation, from his 1613 Voyages.

After the “public rejoicing” that greeted the expedition’s return, Lescarbot recalls how Poutrincourt, at Champlain’s suggestion, established the Order of Good Cheer (L’Ordre de Bon Temps) to ensure that the colonists had a healthy, balanced diet. Each day a different man was appointed chief steward and made responsible for supplementing the usual fare with some special fish, meat, or fowl. These meals were often attended by “the Sagamos Membertou, and other chiefs” of the Souriquois, who “sat at table, eating and drinking like ourselves. And we were glad to see them, while, on the contrary, their absence saddened us . . .” (II:344). Consciously using the honorific Mi’kmaq word for chief (Sagamos), Lescarbot claims that the French shared a mutual admiration with the Native people, les Sauvages – a term encompassing a range of meanings not at all fully reflected by the English word savages (Miller 31–32): “[A]nd hereby one may know that we were not, as it were, marooned on an island . . . for this tribe loves the French, and would at need take up arms, one and all, to aid them” (II:344).Whatever the truth value of this claim, and despite the problematics of Lescarbot’s Franco-Christian imperialism and Noble Savage romanticism, he remains consistent throughout the History in praising these people “of noble and generous heart” and “great liberality” (II:352). The local inhabitants comprised for Lescarbot one of the primary elements of his community’s complex ecology of survival, which included the physical environment itself, the real and symbolic power of Poutrincourt, and the food and drink, both real and symbolic, at the dinner table and in The Theatre of Neptune.

Scholars have described The Theatre of Neptune in New France as a pageant, a triumphal entry (entrée), a réception, or a masque – all of which are sometimes subsumed under the term fête, or court festival. In his book on the theatre of early French Canada, Leonard E. Doucette explains that the play falls within the European tradition of “public masques and triumphal entries, the nautical extravaganzas and allegorical galas so integral to French (and English) courtly life since the Renaissance. The triumphal entries in particular, where the king’s household received the corresponding cortege coming out from the town through which he wished to pass . . . seem to have influenced Lescarbot’s work” (7). In a typical réception or entrée royale,

[t]he personage was normally welcomed by the more important residents and escorted to his destination where he was offered a feast. In the case of the ruler or his representative, he was also offered reassurances of their loyalty by representatives of the various orders of inhabitants. The entry was the visible sign of a contract between ruler and subject town, the ruler assuring the prosperity and protection of the town by his power; the town, in return, offering its loyalty and all its resources in exchange . . . The ordered form of the entry expressed symbolically the relationship between the entering dignitary and the townspeople, as well as providing an opportunity for communal rejoicing and solidarity. (Fournier 3)

Glen Nichols has identified eight other réceptions performed in French Canada between 1648 and 1810 to receive and honour dignitaries ranging from the headmaster of a school to the governor of Québec. Like The Theatre of Neptune, all were produced expressly for one particular event and all directly address by name at least one individual present in the audience for the performance (Nichols 72). In Lescarbot’s pageant the god Neptune and his Tritons along with the Indians and the “companion of jolly disposition” from the colony offer their praise and allegiance, their loyalty and foodstuffs directly to Poutrincourt, the King’s representative and living symbol of French power, on the occasion of his safe return. Through the symbolism of performance, the play dramatically reinforces the contract between ruler and ruled that promises the subjects’ survival and prosperity in return for their fealty.

Lescarbot’s nautical spectacle cites a full century’s development of the European arts of courtly celebration. As Roy Strong argues, “A tremendous revolution had taken place in which, under the impact of Renaissance humanism, the [medieval] art of festival was harnessed to the emergent modern state as an instrument of rule . . . [I]ts fundamental objective was power conceived as art . . . In the court festival, the Renaissance belief in man’s ability to control his own destiny and harness the natural resources of the universe find their most extreme assertion” (1984, 19, 40).Drawing on classical mythology and the sometimes arcane language of neo-Platonic emblems and devices, these celebrations affirmed visually and verbally the magnificence of Renaissance rulers in their ability to effect spectacular transformations in both the natural and human realms, enabling a harmony “which centred on political power being a reflection of a geocentric universe” (40).

The learned Lescarbot would have been familiar with these spectacles not only through first-hand experience but via the print and visual forms, including elaborate published accounts with engravings, by which most major events of this kind were recorded. For archival and political purposes the court festivals and royal entries were preserved in manuscripts, statues and triumphal arches, and printed festival books: “[T]he whole effort of memoria engaged in by every court during this period . . . [was] driven by the desire to mitigate the transience of an event by pinning it down for posterity, by the necessity to manufacture the official story of that court in order to create fama