Читать книгу Safekeeping - Jessamyn Hope - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAdam trudged up the darkening country road with a giant centipede stuck to his back, wiggling its army of legs. He could see to the top of the hill, where the road ended with the gate to the kibbutz. A rusted wrought-iron sign arched over the entrance, stamping the yellow sky in both Hebrew and Latin letters: SADOT HADAR. Fields of Splendor, his grandfather had taught him. The eucalyptuses towering along the left side of the road refreshed the air with their sweet, medicinal scent. To the right, horses grazed in a willowy meadow, and beyond them, a sliver of moon floated over the shadowed face of Mount Carmel. Was this what his grandfather saw when he first approached the kibbutz? Adam wiped his brow. He was sweat-soaked. His jaw ached from clamping his teeth, and his swollen feet felt fused to the insides of his sneakers. But it could’ve been worse. Last time he went cold turkey, the centipedes were crawling out of his mouth.

He reached the kibbutz’s guardhouse without the young soldier inside noticing him. Hunched over his desk, the soldier pored over handwritten sheet music.

Adam knocked next to the window. “Hey, hi. I’m here to volunteer.”

The soldier startled. “What?”

“Hi. Me. Volunteer.”

“I wasn’t told to expect a volunteer.”

Adam had heard anyone could volunteer. This soldier, this kid, better not turn him away. “I didn’t register ahead of time. I hope that’s okay. My grandfather—”

“Are you cold?”

“Excuse me?”

The soldier looked him up and down. “It’s the end of April. Twenty-eight degrees. Why the jacket?”

“’Cause it’s not twenty-eight degrees or whatever that is in Fahrenheit in New York. I just got here.”

The lips at the end of the soldier’s long pimpled face pressed together. He sighed, put down his pencil. “Take it off.”

Adam did not appreciate being ordered about, especially from someone who didn’t look eighteen years old. The jacket had to stay on. He was clammy and shivering and taking it off might freak out the centipede hiding underneath. He wiped the sweat dripping into his eyes. “Seriously?”

The soldier pushed away from his desk and picked up his M-16, making Adam regret not doing whatever the hell the kid asked. The last thing he needed was to make a scene. He dropped his backpack and tore off his jacket while the soldier, rifle slung on his shoulder, stepped out of the booth, surprising Adam with his gangly height. Even with his poor posture, the kid was half a head taller than him, and almost as skinny, the green army uniform hanging off his bony shoulders and hips. Adam resisted the urge to hug himself, but he couldn’t stop his teeth from rattling. His cold, damp T-shirt clung to his skin, and the pungency of his own BO revolted him. He hadn’t showered in a week. At least.

The soldier pointed at his backpack on the ground. “Open it.”

Adam grabbed the backpack, unzipped it, and tried to hand it over.

“Just hold it open.”

The soldier dipped his lanky arm inside the bag and shuffled around the two balls of socks and one pair of boxer shorts. “You’re here to volunteer, and that’s all you’ve packed? Two socks? Where’s your toothbrush?”

The El Al security girl had confronted him with the same questions at JFK, moments before two other security personnel wearing radio earpieces appeared. As those guys silently led him from the spacious terminal through an unmarked door and into a small windowless side room, his heart thumped so hard he feared he was going to black out. To his relief they didn’t search his pockets or body cavities, only grilled him with a hundred questions about his lack of luggage and where he went to school and why was he was jackhammering his leg; they even asked if he believed in God and then why not. After surviving that interrogation, once he was up in the sky, out of the five boroughs for the first time, gazing out the oval window at the tiny glinting ocean waves far below, he figured he was safe, at least when it came to the police. But maybe that was wishful thinking. This was 1994, after all. Everything was so high-tech. What if the NYPD somehow identified him and transmitted a worldwide warrant for his arrest? He pictured his name and face streaming out of a million fax machines, and the centipede crept up the nape of his neck. The effort it took not to swat at it made him shudder.

“I travel light.”

“Did you come here straight from the airport?”

“Yeah, on the bus. Got off at the stop down the hill.”

“Give me your plane ticket. And passport.”

Adam pulled his documents out of his back pocket, thinking he had to keep cool. Not lose his head. This pimply Israeli soldier couldn’t know anything about Weisberg’s Gold and Diamonds on Forty-Seventh Street. If Mr. Weisberg was well enough to talk—and Adam hoped with all his heart that he was—he still didn’t know Adam’s real name. The no-frills family-run store didn’t seem to have a security camera, and even if it did, the picture on those black-and-white videos was too fuzzy to make out facial features, not to mention that everything happened in the back room; at most they had a tape of a blurry figure moseying in and out of the front shop, even saying, “Goodbye, Mrs. Weisberg!” All this soldier wanted to do, like the El Al guys at the airport, was make sure his lack of a toothbrush had nothing to do with “Allahu Akbar.”

After the soldier compared the ticket to the visa stamp, he turned to the passport’s picture, peering at the photo and up at Adam and back at the photo. Adam wished he still resembled the handsome guy in that picture, the guy girls likened to Johnny Depp when he was on 21 Jump Street. He still had the thick inky hair, but it was overgrown, shaggy, not artfully crafted into a messy pompadour. Dark circles surrounded the black eyes he inherited from his grandfather. His sharp cheekbones, straight nose, and thin lips were now too sharp, too thin, and his olive skin had a greenish cast. Most disgustingly, a few cavities had turned black. What he wouldn’t do to be washed and put together, like in that photo, taken only two years ago, when he was sixteen months clean and still a person somebody could love.

The soldier asked if he was Jewish.

“Yeah.”

“Socco. . .” The soldier struggled to read the last name. “That doesn’t sound Jewish.”

“Soccorso. You never heard of a pizza bagel? My mom was Jewish.”

“Was? She isn’t Jewish anymore?”

“I don’t know. Are you still Jewish when you’re dead?” It came out more aggressively than he intended. He had to sound nicer.

Instead of getting riled up, however, the soldier softened his voice. “Did your father convert?”

“Honestly, I never met him. I was brought up by my grandfather, my zayde. He was Jewish. He used to live on this kibbutz. After the war.”

“Really? Do you speak Hebrew?”

“Only the usual: schlep, putz, schmuck.”

This got no smile. The soldier said those words were Yiddish and took the passport back with him into the guardhouse, where he flipped on its ceiling lamp. Twilight smudged the world beyond the glow of the guardhouse, hiding the horses in the dusky fields, flattening the mountain to a black silhouette sprinkled with village lights. A blue and white banner tied to the kibbutz’s chain-wire fence fluttered in the breeze: A STRONG PEOPLE MAKES PEACE.

The soldier opened an oversized logbook and skimmed through the pencilings on the last page. The logbook, with its battered leather cover, looked like it could have been here fifty years ago. They hadn’t gotten any fax about him. Adam wasn’t even sure the kibbutz had a fax machine.

The soldier paused before writing. “Did your grandfather really live on Sadot Hadar?”

“He did. For three years. He was a Holocaust refugee.”

The soldier proceeded to copy the information from Adam’s passport into the logbook. “I’m going to let you stay here tonight, but you should’ve signed up through the Kibbutz Volunteer Desk.”

Adam exhaled. “Thanks, man. Thanks so much.”

The soldier handed back his passport. “You can have room eighteen. I don’t have a key to give you, but nobody uses keys around here. To get to the foreign volunteers’ section, walk straight and make a right after the jasmine bushes. Tomorrow, see the kibbutz secretary, Eyal, about being a volunteer. If you don’t see Eyal first thing in the morning, you’re going to get kicked off the kibbutz, and I’m going to get in serious trouble.”

“First thing in the morning, I promise.” Adam hardly got the words out before the soldier was back to his music sheets, rubbing out a bar of notes as if he’d never been interrupted.

Adam zipped on his leather jacket and walked into the kibbutz. He followed the road, feeling uneasy in the quiet. This was unlike anywhere he’d ever been before. Dark feathery cedars loomed against a violet-blue sky. Fireflies flashed over a tenebrous sweep of lawn. Crickets chirred. As he passed the small, boxy white bungalows, he heard the modest lives inside: a running faucet, a woman’s raspy laugh, a TV chattering in Hebrew. His grandfather must have felt out of place his first night. Homesick. Homesick for Germany? That seemed impossible, and yet, as long as Adam could remember, a pencil drawing of a gaslit street in Dresden had hung in their apartment in New York. Their apartment. The thought of it stoked his nausea, and he cupped his stomach as if that could keep down the horror. Fearing he might throw up, he staggered alongside a high hedge dappled with small white flowers. Were these jasmine? Their cloying perfume didn’t help his nausea. When the hedge ended, he saw a wooden sign marked VOLUNTEERS.

He descended some steppingstones into a sunken quad flanked by two long, single-story buildings. Lined with doors and covered in cracking white stucco, the buildings resembled the run-down highway motels in action movies where criminals and vigilantes always took refuge. Adam had holed up in a number of shabby hotels, but they’d all been in the city and had at least four shabby floors. In the center of the quad bloomed a solitary tree, its flowers still red in the dimming light. On a picnic table beside the tree, a half-full bottle of gin or vodka stood amid crushed beer cans, its clear liquid catching the moonlight.

A glance at the nearest doors—1 and 9—told him 18 was at the far end of the quad, meaning he would have to pass that bottle. He could do it. He’d made it through an eleven-hour flight without accepting one of those cute thimbles of free booze. But then the withdrawal hadn’t kicked in yet. Not like now, clawing at the back of his ribs, making him shudder like an old air conditioner. To be safe he would avoid the bottle by circling behind one of the buildings.

He walked around the right-hand building, down the narrow gravel alleyway between its back wall and a three-foot bank. The rear windows looked into spartan dorm rooms meant for two, similar to the ones at Lodmoor Rehab: a bed and dresser against each sidewall, gray wool blankets, a few makeshift decorations pasted to the walls, mostly pages ripped out of magazines.

He stopped. In the next window, a young woman stood naked before a full-length mirror. The window had no pane, no bug screen, only the open white blinds striping the scene. Her back was to him: a dark line dividing her round ass cheeks; two dimples at the base of her back; a lovely waist; shoulder-length hair dyed an unnatural Raggedy Ann red. The mirror revealed her front, the V-shaped thatch of brown hair nestled beneath a flat stomach, and her beautiful breasts. Sweetly buoyant, but with womanly heft. Nipples like the flushed cherry blossoms his zayde took him to see every spring at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

It was surprisingly hard to look away from a naked woman, even when he felt no arousal. And it wasn’t only her nakedness that arrested him, but the intensity with which she studied her reflection, her face stern, eyes exacting, like a general evaluating a battle plan. She turned to scrutinize her profile, and her lips pursed in disappointment, anger. She did have something of a schnoz, but that would’ve only made her more desirable to Adam if he were able to feel desire; he didn’t like perfect, always had a soft spot for nearly perfect. But it had been two months since he’d had a hard-on. Even longer since he last managed to get himself off in a porno booth on Eighth Avenue.

When the girl leaned close to the mirror to draw on eyeliner, he managed to tear his eyes away, but as he did, he caught sight of another woman in the room, curled on the bed beside the mirror, a mop of chestnut hair covering her eyes, a brown skirt tucked over her knees. Her mouth moved as if she were endlessly whispering while her hands fidgeted with . . . what? A silver crucifix hung off the side of the bed. It was a rosary. She was saying Hail Marys. What a strange picture these two women made together.

The naked girl’s head jerked toward the window. His heart leaped. Had he made a sound? Could she see him in the darkness beyond the blinds? If he walked, would the gravel’s crunch give him away? He couldn’t think, his head too foggy. He failed to move; only his mouth fell as the girl’s deep blue eyes, bordered in thick black kohl, landed on his. She turned her body to face him, standing tall, not covering herself up. Her stare was inscrutable. Was it anger? Playfulness? Power? All of the above? He wanted to tell her that he felt nothing, nothing lewd, that it was like viewing an old painting in the Met. While the other woman, seemingly unaware, continued working through her Rosary, the naked girl grabbed a hairbrush from her dresser and hurled it at the window.

Adam bolted. He beat it down the length of the building, listening for an outcry. All he heard was his panting and the crunching gravel as he threw one foot in front of the other. He ducked around the corner of the building and collapsed against the wall, panting for air. The veins at his temples thrummed, feeling like they might pop. He unzipped his jacket and clutched the T-shirt and skin over his heart, over the stabbing that he might have mistaken for a heart attack if he hadn’t been through withdrawal too many times. It was brutal, making a break for it while detoxing. And for the second time in twenty-four hours. Could that rush through the Diamond District really have been this morning? Traveling such a far distance warped his sense of time.

His breath returning to him, he leaned his head back on the wall. Above was an unfamiliar sky—black, star-ridden, bottomless. So that was the Milky Way: a band of stars streaked across the universe like a ghostly line of coke. It was frightening, this sky. He preferred the one back home: polluted and starless, all the twinkling on the ground. This sky made him feel like he had to be kidding, thinking anything people did mattered. Anything he did to anyone. But that wasn’t true. He must have looked like a Peeping Tom, there at her back window. Imagine coming all this way and getting kicked off after five minutes because of something so stupid. He had to be more careful. He couldn’t fuck this up. This was his last chance.

He peeked into the quad, praying the girl wasn’t standing there with the soldier or a boyfriend out to prove his worth. She wasn’t. Some young guys now sat around the picnic table, laughing and talking in what sounded like Russian. They didn’t seem to be on the lookout for anyone as they passed around that bottle.

Adam walked fast for room eighteen and knocked on the door. Afraid the girl might come out, he didn’t wait for an answer before turning the knob and slipping inside. Luckily, he didn’t appear to have a roommate. The beds were made. No personal belongings anywhere.

Leaving the lights off, he hung up his leather jacket and sat on a bed. He didn’t immediately lie down. He felt too guilty, like he didn’t deserve to lie down. Like he might never deserve to lie down for the rest of his life. Untying his blue high-tops for the first time in days, he gently freed his throbbing feet and lifted his legs onto the mattress. He slowly lay back onto the scratchy wool blanket. As his head lowered onto the pillow, it exhaled a detergenty smell. He stared at the closet door, where a Mikey Katz had scratched into the wood that he was here in ‘82. Where was the centipede? It had crawled away, but his teeth still chattered if he didn’t clench them. Was it only the withdrawal making him shake, or also his conscience? He would know soon enough. Through the back window came an owl’s low-pitched hoot, repetitive like a car alarm, yet soothing.

If only it were two years ago, and he were lying in his bed on Essex, the city lights pouring through his second-floor window, blanching the Nirvana poster. The cast of old Star Wars figurines on his bookcase. The college textbooks neatly piled on his desk, the wooden desk that had belonged to his mother when she was young. Closing his eyes, he would be surrounded by all that comforting sound, people shouting on the sidewalk, the hum of the idling delivery trucks, the occasional ch-ch-cha of maracas when the door opened to the Mexican restaurant on the ground floor, and Zayde’s scratchy swing records playing in the next room: After you’ve gone and left me crying, after you’ve gone there’s no denying. Might Zayde, when he was only five years older than Adam was now, have slept in this very room? No, this building wasn’t old enough. And hadn’t he mentioned a tent?

Adam turned on his side, reached into his jean pocket, and pulled out the brooch. He’d had a glimpse at it in the airplane bathroom, but this was his first chance to take a good look since stealing it back. He tried to blur out his hands—the fingertips blackened on crack pipes, the nails packed with grime—and see only what they were holding, that one-and-a-half-inch square. Just a one-and-a-half-inch square. And yet.

The first time Adam saw the brooch he was eight years old. He’d awoken from a nightmare and was on his way to sleep with his grandfather, as he often did that first year he lived with him, when he was stopped in the doorway. He had expected to find the old man sleeping, but he lay awake in his green pajama set, canted on his side, as Adam was right now, studying something small in his hands, his eyes glistening in the lamplight. Adam tiptoed into the tidy bedroom, so different than his mother’s, where he’d had to navigate around dirty clothes and empty wine bottles to reach her passed-out body, half covered by a stained T-shirt.

His grandfather only noticed him when he climbed onto the foot of the mattress. “Another nightmare, Adam?”

Adam nestled behind his grandfather’s back and peered over him at the radiant square, like something from a fairy tale. “What’s that?”

“This?” His grandfather returned his gaze to the brooch. “This is . . . a very special thing.”

“What’s so special about it?”

His grandfather sat up, slipped on his plaid slippers.

“I’m afraid it’s not a story for little boys. But I promise to tell you one day.” He looked back at Adam, laid a hand on his shin. “Maybe when it becomes your brooch.”

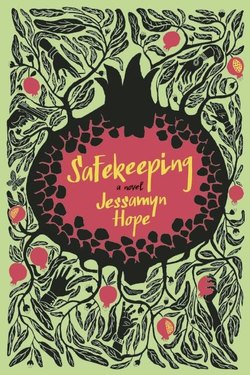

In the dark dorm room, the brooch seemed to stare at Adam as much as he stared at it. An uncut sapphire, the size and shape of a Milk Dud, glowed in its center, so blue. Pearls and smaller gems, also in their natural shapes, hemmed the edges of the brooch—red rubies in the corners, and, halfway between, either a purple amethyst or green garnet. It was the rich gold filigree that stirred Adam, though, far more than the precious stones; in it, he sensed the long-dead goldsmith who had painstakingly fashioned the tangle of thin vines and little flowers that covered two of the brooch’s quarters, as well as the small pomegranates and leaves in the other two. Adam, having never seen a pomegranate and not entirely sure what they were, thought they looked like small round heads wearing those funny three-pronged jester hats, but the jeweler, Mr. Weisberg, had explained they were stylized pomegranates. He couldn’t bear to think of the jeweler, but didn’t he say one of the flowers was missing a petal? Adam brought the brooch closer to his eyes and searched for the one with only five. It took a moment, but there it was, in the bottom left. A little malformed flower. It was such a heartbreaking mistake. So tiny most people would never notice. But Mr. Weisberg had.

There was that ache again, that pressure against the back of his breastbone, so familiar, but more painful than ever before. He cupped his hands around the brooch and curled into a shivering ball.

He had no illusion that his zayde was up in heaven right now, watching him. The old man would never know that his grandson had come halfway around the world to set things right with his brooch.

But he had. He was here.