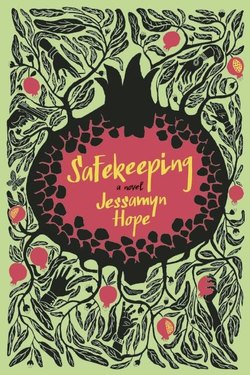

Читать книгу Safekeeping - Jessamyn Hope - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMother shit pizdets fucking ebanniy kibbutz, thought Ulya as her green stilettos kept lodging in the soil of the cabbage field. But what was she supposed to do? Meet her lover in work boots? A gust of wind blew a strand of red hair into her gluey lip gloss. As she tried to pick the hair off her lip, her shoe jammed again, and a bare foot with freshly painted fuchsia toenails slipped out and plunged into the mud.

She slipped her mucky foot back into her shoe and scanned the world around her: the rows and rows of cabbages, the modest white houses of the kibbutz on the plateau, the smattering of village lights along the black mountaintops. How long was she going to have to live in this dusty corner of the world surrounded by Jews and Arabs? Until fifty years ago, half the people in her hometown of Mazyr had been Jews, but it was difficult to imagine when the only evidence was the eighteenth-century cemetery overlooking the Pripyat River where cows and goats grazed among sunken stones. It was off one of these stones that she stole the name for her fake Jewish grandmother.

At last she reached the fragrant grove where the trees were swollen with ripe mandarins and the leaves appeared gray in the moonlight. The hard orchard dirt allowed for easier walking and a more optimistic train of thought. When the USSR announced they were letting Jews leave for Israel, she had jumped at the rare chance to get an exit visa, and what was the use of blubbering about it now? So what if by the time she got the visa the Union had crumbled? Life in Belarus still wasn’t a bowl of raspberry jam. In her last letter, her mother wrote that she now wrapped her feet in plastic bags before slipping on her shoes because the spring puddles seeped through her worn-out soles. Ulya was lucky to have found a way out, and soon she was going to be in New York City. Of this she had no doubt. She doubted almost everything—politicians, religions, isms in general, science, declarations of love, even her family—but one thing she knew she could depend on no matter what: Ulya. With her dyed scarlet hair, she likened herself to molten lava, a smoldering force that coursed through the world dissolving anything and anyone in her way. She shook her head, amused by her own melodrama.

A match flared in the trees up ahead, making her stomach turn. Why did she keep coming to see this man? She watched the orange cigarette tip rise and fall in the darkness. This was very un–molten lava of her. Stupid. He wouldn’t help her get to New York. That new boy, Adam of Manhattan, perhaps he could help her. But how? She couldn’t imagine falling in love with him: he was so skinny, with purplish bags under his eyes, and all he talked about was his grandfather. She might be able to pay him to marry her, to be her green-card husband—he smacked of someone who might go for that sort of thing—but how much would she have to pay? If it was anything more than nothing, she didn’t have it. What if he fell in love with her? Maybe he would marry her for free, without her having to pretend she loved him, in the hopes of winning her over? This didn’t seem likely though. He showed surprisingly little interest in her, even after seeing her naked. Was it because she was nothing compared to the women in New York?

Ulya’s heart had been set on living in that city of cities for eight years now, ever since that day she was working beside her mother selling dried fish on the platform of the Mazyr train station, and a stunning woman stepped off the Minsk-Kiev express wrapped in a sable fur coat with the most lavish cape collar. November 1986, only a few months after the radioactive rains, and her twelve-year-old self couldn’t take her eyes off the woman as she sashayed toward their small stand with her high sleek ponytail and ballerina posture.

The woman bestowed a smile on her, white teeth glistening between painted red lips, and turned to her mother and ordered fifty kopeks of vobla in a Moskva accent. As her mother selected the best fish from her offerings, the woman explained that she would never eat food from so close to Chernobyl, but it was good enough for her cat. The woman’s luminous skin and rosy cheeks made Ulya embarrassed by her mother’s faint mustache and the large chin mole that echoed the black eyes of their dried perch.

A man in sunglasses and a shiny mink ushanka strode toward their stall with open arms. “Hey, privyet! Look who’s here!” The woman put down her red leather bag, and they stood, clasping each other’s arms, gushing over what a delight this chance encounter was and how splendid the other looked. Seeing her mother was too transfixed by the beautiful people to notice anything else in the station, Ulya dropped to her knees and crawled around the fish cart until her extended hand could snatch something, anything, out of the woman’s bag. Before she had acknowledged what she was doing, she had done it and was back on the other side of the fish cart fumbling to hide a manila envelope in her coat. She had never stolen before, not even a fruit dumpling from her mother’s kitchen.

Fortunately the train started at once, and the woman grabbed her red handbag and paper-wrapped fish and ran laughing with her male companion toward her car. Ulya’s luck continued when, as soon as the dark green caboose chuffed out of the station, her mother mumbled that she was going to the toilet. Ulya knew she was also going to pay the station guard his bribe before he had the chance to mosey over and insinuate how much trouble he could get in for letting them sell their fish. Impatient to see what was in her secret envelope, Ulya watched her mother trudge across the railroad tracks and climb onto the opposite platform, her charcoal coat and brown headscarf matching the rusty tracks and cement station building. The giant red digital clock above the station’s doors seemed the only color for miles. The second her mother disappeared through the doors, followed by the guard, eager for his ten kopeks, Ulya whisked the envelope out of her coat.

Fingers raw and stiff from having lost her gloves earlier that winter, she struggled with the fastener, the red string seemingly wrapped around the buttons a hundred times, but at last she got the envelope open and pulled out—a fashion magazine! In English! Between glances to see if her mother was returning, Ulya riffled through the vivid pages, glimpsing legs in bold purple stockings, unnaturally red or platinum blond hair, shiny high heels, gold purses, and outrageously padded shoulders. A two-page spread featured a dizzying nighttime wonderland where yellow cars streaked down streets and glittering towers pierced the black sky with silver and gold pinnacles; it would be a year before she dared to show the magazine to a classmate’s father, a playwright rumored to be lax about contraband, and learn that this place was real and called Manhattan.

While she and her mother waited for the next train, her mother turned to her. “Why do you stare at me? I disgust you, selling vobla?”

Ulya had been busy daydreaming about later that night, when she would study the magazine behind the locked bathroom door, and had forgotten that her mother was even there. “No, Mamochka.”

Her mother shrugged and absently rearranged the fish. “You will grow up and you will see. Learn for yourself. That in life you don’t have a choice. It is what it is.”

Ulya peered sideways at her mother, wiping her stinky fish hands on a tattered cloth, and considered for the first time whether one of her parents might be wrong. It felt like betrayal to think such a thing, but she couldn’t believe she had no choice, no say in who she could be or what she could have. Look! She had chosen to snatch the magazine, and now its magic was tucked inside her coat.

Ulya straightened her jean skirt, reaffirmed that the cropped pink T-shirt showed off her flat stomach, and faced the shadows of the mandarin grove where the useless man awaited her. This fling was for the time being. While she was stuck in this boring collective-farm hell, spending her days in a windowless milk house, straining yogurt. She was young, and flings were a part of being young. If he got all caught up in it and had his heart broken, that was his fault. It wasn’t her responsibility to look after other people’s hearts. She had never had her heart broken. Why? Because she was so beautiful nobody would leave her? No. Because she took care of hers and didn’t stupidly hand it over to someone else to safeguard.

When Ulya reached the barbed wire that ran along the perimeter of the kibbutz, she called, “Farid!”

Her Arab lover rose from where he’d been sitting on a boulder. He approached the cattle fence, his wide smile betraying how thrilled he was to spend another night lying with her among the hill’s wildflowers and silvery olive trees. Ulya’s stomach stirred again, but in excitement. Though they had been meeting like this for half a year, it still surprised her how coppery-gold his eyes were, even in the shadows. She had to grant him that much: he had extraordinary eyes.

Farid chucked his cigarette, leaned over the moonlit barbs, and kissed her, not only with his lips, but with the smell of tobacco and coffee and musk and a grassy whiff of the kibbutz’s avocado orchard, where he had worked all day.

“What’s this?”

She felt him tugging on the back of her T-shirt and realized she had forgotten to remove the price tag.

“Oh, it’s new.” She hurried to rip off the tag before he saw the price. It wasn’t even that expensive, not even a hundred shekels, but still, if he saw the price he’d know she couldn’t possibly have bought it. And he wouldn’t like that most of her clothes were shoplifted.

He brushed her exposed belly. “It’s a nice shirt.”

She gave him an aren’t-you-lucky look.

He pulled on the top barbed wire and stepped on the lower ones, creating a hole for her to climb through. Ulya shook her head at the way he parted the barbed wires, as if he were holding open a shiny car door for her.

“I don’t know why I come here,” she said.

Farid grinned. “I do.”