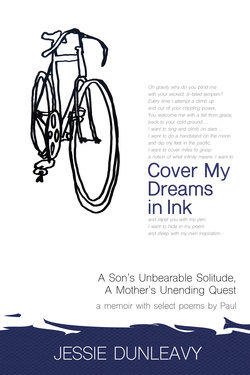

Читать книгу Cover My Dreams in Ink: A Son's Unbearable Solitude, A Mother's Unending Quest - Jessie Dunleavy - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Running Toward Morning’s Doorway

Miracles are sometimes stretched few and far between hardships.

And though battles may rage in our communities

and though our hearts keen sense of injustice may be felt;

when miracles surface, they will carry us back to refuge.

DESPITE MY MOSTLY optimistic outlook, juggling life’s demands as a parent, a homeowner, and a professional presented challenges. Sometimes I felt buoyed by my ability to manage, and manage well. Sometimes I was lonely; other times I felt discouraged by competing needs that pretty much ruled out my ability to live up to my own standards, at work or at home.

When the children were still pretty little, I signed up for an exercise class that met one time a week in the early evening, something I saw as a luxury but good for my overall health, even though I’d have to figure out childcare each week as the day approached. To enable my getaway one winter evening, I took Keely and Paulie to my neighbor’s house.

By the time I returned home, snow had accumulated, and I decided to steal a few extra minutes to run inside, grab the broom, and clear our front steps and walk before having the children underfoot. Later, when the three of us were settled back in the house and I was getting dinner together, a gust of bitterly cold air whipped in from the playroom, prompting me to yell to the kids, “What is wrong with you? Close that window! It’s winter, for God’s sake!!”

Keely, the appointed spokesperson for the twosome, came into the kitchen and said, “We didn’t open the window, Mommie.”

I walked in there. The window was wide open. I closed it before noticing the shards of glass at the top of the basement steps. Checking for additional signs that would help calibrate my reaction, I went upstairs and discovered my ransacked bedroom and eventually my missing jewelry. The police came and investigated, telling me the thief had entered by breaking the basement window. They surmised he was caught off guard when I returned home, and, rather than exiting via the front door, he jumped out the playroom window located at the back of the house and beneath which they could see his footprints in the snow. I knew then that I had startled him when I ran in for the broom and was thankful I hadn’t come in to stay, with the children in tow.

The whole thing unnerved me. I soothed the kids, fed them, and began to clean up the mess and anticipate the repairs, the insurance claims. I would not have considered myself a jewelry person, and was far from dripping in anything, but when adding up every piece of jewelry accumulated in your whole life, it’s more than you’d think. I learned that without a separate rider for jewelry on my homeowner policy, the coverage would be a mere fraction of the total value of what I’d lost.

My insurance agent then suggested I reconsider and take out a jewelry rider on the policy. While I could have cried, I actually laughed. “Run this by me one more time,” I said to him. “Despite my years of premium payments, you can’t pay me the money to cover my loss but, instead, I can pay you additional money to cover that which I no longer have and cannot replace. Is that what I heard?”

I was sad mostly for sentimental reasons. Among the things I lost were a gold charm bracelet my parents had given me for my sixteenth birthday with accumulated charms representing many a milestone. Also gone were gold earrings my father had given my mother, gold cufflinks she had given him, my engagement ring, the diamond bands Don had given me when each of the children was born, and a watch I loved. Sometimes I still wish I had those things, but they were just things.

Don had remarried as soon as our divorce was finalized, just as Paul was entering pre-kindergarten and Keely second grade. While he didn’t tell me or the children directly, I had heard about the engagement and the pending wedding. From the start, his relationship with Lucy ushered in a more regular visitation schedule, which I welcomed—just as I did the fact that Lucy was a likable and family-oriented person. One has no say in who will become a step-parent to their children; let’s just say I was grateful. Some years later, Don and Lucy would have their own child, a daughter named Annie.

Even though life was full of challenge, I wasn’t interested in pursuing a relationship during my first couple of years as a single parent. Without giving the matter much thought, I instinctively focused on the children. In any case, they were my highest priority and their world had been disrupted enough. And frankly, even in my younger carefree days, I valued breathing room between romantic relationships.

It stands to reason that another influence on my thinking was rooted in the heartaches of a failed marriage. But regardless of the forces at play, about which I am not entirely sure anyway, we were a pretty happy threesome—Keely, Paulie, and I—and even took to calling ourselves “three peas in a pod,” a reference to our bond that cropped up now and again in many a light-hearted moment for the duration of our years together.

Eventually, however, I agreed to unleash one particular friend, Linda, whose extroverted personality suited her matchmaker aspirations. Since this was the 1980s, there was no such thing as Match.com, but Linda’s reconnaissance on my behalf would stand up to any comparisons. Linda was a born social butterfly who was pretty, and she knew it. And while she was a faithful wife and a devoted mother, she loved to flirt and was in her element in scouting out men. Linda recruited several candidates, each of whom met her rigorous criteria: nice looking, social, and successful. Over time, she introduced me to a lawyer, an airline pilot, and a judge. As a result, I dabbled in the dating world and admit I did have some fun, even though I often felt it was more trouble than it was worth, mainly because I shielded the children from my activities.

One date stands out. Mike, the attorney, invited me to go out on his boat with another couple. We agreed to meet at the dock at the end of my street and from there motor over to Mill Creek for dinner at Jimmy Cantler’s Riverside Inn, a wildly popular waterfront crab house, an Annapolis icon. I had not met Mike or his friends but was instantly at ease and enjoyed the cruise and the dinner.

Navigating the waterway in and out of Whitehall Bay—linking Mill Creek to Annapolis’ Severn River—is tricky, something I knew well. The Bay is deep and narrow, with shoals on either side, requiring careful attention to channel markers and charts. We made it in without any problem, as had always been my experience, but got stuck on the way out, a situation that was made worse by the motor getting hopelessly tangled with crab pots, abundant in this particular area.

Keely and Paul’s babysitter that evening, Andrea, was a young teenager who lived in the house directly behind ours, and I had told her I would be home by 11:00. I think we ran aground about 10:30. Efforts to free the boat, followed by attempts to flag down another boater, failed and eventually my three companions—none of whom had children at home—went below to sleep. I sat there all night, helpless, with no possible way to communicate. My degree of misery was such that I contemplated swimming, but I decided a temporarily missing mother was better than a dead one. Still, my suffering grew along with the seemingly endless night.

As the sun finally peeked over the horizon, I was able to wave down a passing boater who agreed to take me to the City Dock, less than a mile from home. I will never forget walking into my house, disheveled and in my rumpled dress, where I found Keely and Paulie at the kitchen table eating cereal. Seated with them was Andrea’s father, who had relieved his daughter at some point and stayed the night at my house, no doubt waiting . . . wondering . . . I was so sorry! How I looked, how the situation seemed, I can only imagine. The same goes for what poor Keely and Paulie thought upon realizing my absence as they got up that morning, seeing my made bed without me in it. And Mr. Seabrook’s presence! I had some explaining to do.

I used to think of that as the worst night of my life, often recalling it as Andrea—who in the blink of an eye grew up to become a successful journalist—hosted favorite programs on NPR, and even now as I continue, some thirty years hence, to catch up with her parents over the back fence.

Throughout my time as a single parent with young children, I was lucky to have bonded with several neighborhood teenagers, one of whom—Molly Wanamaker—became family to us. Molly was eleven when she first knocked on our door, and she helped me in countless ways until she left for college—and even then was a presence during school breaks and throughout the summer months, whether or not I was going out. We baked cookies together, carried out the work of Santa Claus, and battened down in preparation for a hurricane barreling up the Atlantic. Molly would spend the night sometimes, and even vacationed with us and my extended family over multiple summers.

The best thing I had going for me was the camaraderie and the backing of my family, with their unconditional love for the children providing emotional support as well as “another pair of hands” when needed. I took much comfort in the fact that Keely and Paulie hadn’t lost fifty percent of their daily adult network, as would be the case for many children of divorce. In essence, their world continued to include a grandmother, a grandfather, two aunts, and two uncles, all of whom they saw at least weekly and who played meaningful roles in these critical years. In time, I came to see that I was rationalizing the reality of divorce and that—in spite of these very real advantages—recurring sorrows are part and parcel of a fragmented family. Nevertheless, we had plenty of love; there was no doubt about that.

At some point in here I started to date Jerry, a college professor I met through my work. It was a relationship that I was not quick to divulge to the children and one I initially didn’t take very seriously. It was fun; that was all. And I loved teasing Linda, telling her I met him all by myself. But things evolved and we grew closer, with a bond that was enhanced by a common passion for education. Eventually, Jerry asked me to marry him.

As Paul’s second-grade year and Keely’s fifth unfolded, I began to consider Jerry’s proposal. He was more confident than I of the merits of this idea, and I pretty much dragged my feet for the better part of that year. However, in weighing all the pros and cons, ultimately, I was persuaded by several factors. One, Jerry was a born teacher and, despite being childless, he would be a “natural” in a caretaker role. Two, he was highly energetic—having completed his doctorate while teaching full time was just the tip of the iceberg in terms of his productivity—and eager to take on the duties of parenthood. This was explicit as he continually made his case. “Come on!” he’d say. “Tell me—who else has the energy to help you raise your children?”

Also in the plus column was Jerry’s sense of humor and what I saw as his unwavering devotion to me. After all, he was in his thirties and had never married. And maybe, just maybe, six years of going it alone was enough for me.

*

THIS DECISION-MAKING PERIOD coincided with Paul’s year at Annapolis Elementary School. At that time, we had settled on a somewhat satisfactory medication regime and I was thankful for the consistency. I had no complaints with the school per se. Paul’s classroom teacher was kind and supportive, as was the special education teacher, who devoted a couple of hours a day to working with him. Even so, as I dropped Paul off on my way to work each morning, I watched him walk up the front steps of the school, hang his head, and wave to me by extending his arm behind his lower back and wiggling his fingers. I don’t think I rounded the corner from Green Street onto Compromise Street one time that year without tears in my eyes.

While Paul toed the line with little complaint, school was a place where he stayed to himself and, for the most part, was unaware of his surroundings. His teachers reported, for example, that he remained seated at his desk as the other children lined up to go to the cafeteria for lunch. When prompted to join them, he often needed to be reminded to take his lunch box.

Having entered the world of special education within the county system, I would become all too familiar with ARD committee meetings, otherwise known as Admission, Review, and Dismissal—the official name of the committee responsible for making educational decisions for a student. Parents are members of the committee, as are designated educators who bring their expertise to the meetings where together an Individualized Education Program, often referred to as the IEP, is written and the child’s placement is determined. The placement is denoted by a particular “Level,” indicating how much of a child’s school day is spent in a special education setting, with federal laws defining Levels I through V. The higher the level, the more special education services are required.

In an ARD committee meeting in early May, it was evident that, by all measurable standards, Paul’s year had not been successful, and he would need increased services for third-grade. The upshot of the meeting was the county’s recommendation to change Paul’s designated placement of Level III (providing thirteen hours of special education support per week) to Level IV (twenty hours), meaning Paul would have to attend Central Elementary School in Edgewater, Maryland—the only public school in the area equipped to provide Level IV services.

After thinking about this decision for a couple of weeks, I realized I was more puzzled than resolved, and I decided to ask for another review:

%%%

May 28, 1991

Anne Arundel County

Department of Special Education

%%%

To whom it may concern:

%%%

I am writing to request a formal hearing to review the proposed educational placement for my son, Paul—currently a second grader receiving Level III special education services at Annapolis Elementary, a place where he has been well cared for, yet his educational needs have not been met in general or in special education classes. Because Paul has not been successful, Level IV services are recommended for the coming year.

%%%

After further consideration, I must question how twenty hours of services is preferable to thirteen hours, when Paul’s time in the special education setting this year did not meet his needs. In other words, I do not understand how this proposed change—essentially the continuation and extension of the same methods that didn’t enable success—provides hope for improvement for Paul (educationally, emotionally, or socially). In fact, I fear further setbacks as he continues, in a different setting with a different peer group, in a system that cannot cope with his differences.

%%%

Please notify me regarding the appropriate next step for an appeal process.

%%%

Sincerely,

Jessie Dunleavy

%%%

Finding the right school environment for Paul was a conundrum that kept me awake at night, but my pending marriage, initially requiring a little more adjustment on Keely’s part than Paul’s, was a good thing. I looked forward to becoming a family unit and having a partner, a shoulder to lean on, particularly in considering the challenges I faced with Paul, an old house, and a job with increasing demands. Jerry and I were married at the end of the academic year, and he subsequently moved into my home—the only home the children had ever known.

Our strengths included respect for each other’s career and work ethic, good friends with whom we socialized frequently, and the support of my family members who embraced my husband from the outset. But, catching me off guard, significant challenges surfaced early on. Jerry had what I then would have described as temper tantrums.

The frequency of these often frightening outbursts ranged from a couple of times a month to multiple times in a given day. During a typical episode, Jerry would simultaneously shout—launching unfounded and often vicious verbal attacks—and stomp from room to room and up and down the stairs from one floor of the house to another repeating himself over and over. In sum, he lost control and, along with it, the ability to reason.

This behavior was shocking and incomprehensible to me, and initially I was handicapped, thrown off balance by confusion. I know I adopted a protective mode—protecting myself by making a conscious effort to maintain my composure and not let him upset me while also protecting the children to the extent I could, often making light of any verbal attacks they could overhear.

For a long time, I thought my reasonable approach would win out. Basically, I was good at influencing others. Additionally, I was eight years Jerry’s senior and had faced more challenges than he. I was confident in my ability to communicate and to establish standards. At times I thought maybe my efforts were helpful, extending the periods of smooth sailing.

Part of my quandary was figuring out what provoked Jerry’s anger—a piece of the puzzle I could rarely grasp. But even when I could, I didn’t get why his reaction was out of proportion, more dramatic than the circumstance warranted with accusations and personal attacks that knew no limits. And because this correlation with reality was shaky at best, there often was no way out of the labyrinth he created.

Making matters worse, it wasn’t long before these bouts of hostility turned on Paul, whose reactions, depending on the specific situation and his own degree of fragility at the moment, included crying, words of self-defense, and occasionally even assuming a more “adult” role, accepting the assigned blame just to minimize the drama. Nothing worked. Nothing but time.

Generally, somewhere between one and three days after an outburst, Jerry adopted a conciliatory manner, “making things right” with acts of kindness. While I was sincerely grateful for his gestures, he rarely acknowledged his destructive behavior. Nor did he retract the insults that bore no resemblance to the truth. I walked a tightrope—trying to keep the peace, minimize the toll taken on the children, and defend Paul when I could do so without fanning the flames.

One evening, a year into our marriage, Jerry became infuriated because Paul was having trouble completing his homework. I think it’s fair to say every parent in the country, or maybe the world, has experienced similar frustration and may well even overreact as a result. I know I have. But this scenario triggered an episode of outrage on Jerry’s part, and among the hurtful things he repeatedly yelled at Paul were:

“It’s no wonder you can’t read and write like other children your age!”

“You will continue to be weak. I guess you think it’s okay to be weak!”

“Go cry to your mother. She likes you to be weak!”

No resolution was reached and no words of respect or regard were spoken. When Paul was ready for bed that evening, I quietly went into his room to say goodnight and, if nothing else, give him a hug. He asked me if it was true that he couldn’t read and write like other children his age, and I did my best to point out his strengths and to explain the array of differences among various learners, in terms of ability and pace. I also said there were many whose skills may have advanced beyond his, but there were others less capable than he, telling him too that the poor reader may be the fastest runner, or that the child with disabilities may become an engineer, a famous artist, or a world leader.

I usually tried to provide comfort without directly countering one of my husband’s declarations, something I saw as necessary in keeping his reactions in check lest he accuse me of undermining “his authority.”

However, as I left Paul’s room that particular night, I do remember saying, “By the way, Paul, you are not weak. And you know you aren’t.”

“Goodnight, Mom. I love you.”

*

AS SUMMER AND our family’s annual two-week trip to the beach approached, Jerry said to me, “I am not going to do anything with, or for, Paul while we are on vacation, unless you want me to be volatile with him. Actually, it’s your choice; so just let me know what you decide.”

He repeated this for days, always emphasizing that I was in the driver’s seat—it was my choice. Elevating himself to the benevolent position, he reiterated that he would simply go along with my decision. One hardly needs to be a psychologist, or even a tad insightful for that matter, to see that I had no choice. The fact is, this twisted maneuver was nothing but a threat, a strategy to keep me on edge.

In spite of the fabricated land mine I was trying to navigate, we had fun on our family vacations, and I found that the network of adults—whether friends or family—served to keep Jerry’s unreasonable behavior in check. As a matter of fact, the beach trips were good for us, reminding me that we could laugh and be light-hearted.

This particular year, the eight cousins—ranging in age from two to thirteen—could go out unsupervised after dinner in the little oceanfront village where we stayed. One night they were out on foot, except for two-year-old Molly who they put in her stroller with Caitlin, the oldest cousin, at the helm. It was getting dark, and as they approached the path to the beach, they were frightened by a man on the walkway who reportedly was wearing a long black hooded cape—with the hood up, concealing his face. They were spooked and took off running for home! As they burst in the door, breathless, with all of them talking at once, we had to laugh at the vision of them running for their lives, all the while pushing the stroller over some pretty rugged terrain. Little Molly’s hair was slicked back as if she’d been in a wind tunnel! We took some pride in the fact that they didn’t abandon the stroller, given their state of high alert. For the rest of our vacation, they swung into investigator mode, fixated on discovering the real “cape man,” who obviously lurked among us, and deciding whether or not he was a threat to the safety of this otherwise tranquil community. While I don’t think they solved the mystery, theories abounded, and “cape man” was a legend for years to come.

A passage from Paul’s laptop files:

%%%

Of all the places in the world I could want to be, the beach house was the place. It was a place where dreaming stopped and where real living began. All of the memories of the beach in Delaware make me wishful to be a child again, carefree and down at that same beach chasing the crashing waves back into the ocean. If only life could be so simple, I would be a millionaire.

%%%

Back at home, another incident between Jerry and Paul took place that same summer. On this particular day, Paul’s crime was leaving our neighbor’s garden hose running. Our street is lined with old houses that are just about as close together as detached houses can be, so much so that in looking down the street, you see the eaves of the roofs overhanging one another. Our easement, a little more generous than some, provided a narrow side patio used in common with our neighbor Mandy, a circumstance we enjoyed, and one that over the years led to a deep friendship between Mandy and me as well as among her three children—Josh, Danny, and Lara—and my two, all close in age. Not only were the children back and forth between our two houses, but Mandy and I shared garden tools, the lawnmower, detergent, anything and everything.

As Paul came inside, I heard Jerry ask if he had left the hose running. Although in another room, I braced myself.

“Yes,” Paul said.

This prompted an outburst that started with, “That was the wrong thing to do.”

“I didn’t mean to,” Paul interjected.

The drama took its course anyway, as the statement of wrongdoing was repeated with the classic irrational fervor and rapidly escalating personal attacks.

Paul then said, “I won’t do it again.”

Grabbing Paul, picking him up and putting him in a chair while squeezing his frail arms (in front of his cousin with whom he’d been playing), Jerry screamed, “Don’t you ever talk to me that way! You will not treat me like that! I am trying to tell you something! You were wrong! You were wrong!”

Paul started to cry, and Jerry continued to yell: “You never said you were sorry! You don’t care about Mandy!”

Crying harder, Paul said, “Yes, I do.”

Now in full-blown rage, Jerry screamed, “No, you don’t! No! You do not! You do not care about Mandy! That wouldn’t be your style, would it? You didn’t even say you were sorry!” All of this, with the emphasis on Paul’s supposed character flaws rather than his forgetfulness, was repeated more times than I care to report, or even want to remember.

As a school administrator, I advised many a parent over the years, frequently emphasizing the importance of respect (we cannot expect to receive that which we don’t give); modeling the behavior we want our children to assume; consequences for poor choices that are fair and understandable to a child, bearing in mind that discipline is a component of love. And probably the most important: Don’t put yourself on the child’s level. They have to know you are in charge and when you lose your cool, you lose your effectiveness. None of us is perfect, and children press our buttons. We are human and we make mistakes.

But Jerry broke all the rules, and my desire to share my perspective was often thwarted by fear.

For me, being in a therapist’s office had become almost as routine as going to the grocery store, but at this juncture I couldn’t convince my husband of the merits. So his explosive tactics continued despite my efforts and the warnings voiced by a couple of Paul’s teachers and mental health providers. Mundane occurrences, such as a misplaced remote control or the way laundry was folded, could prompt a no-win interrogation followed by a blow-up and literally days of hostility.

In some ways I became immune to the yelling, but he employed other subtle forms of manipulation, strategies to belittle me or trivialize what mattered to me. One school morning when Paul was a little older, we were having breakfast when Paul announced he needed to take a set of dress clothes to school for that day’s mock job interview.

Mildly impatient with him, I uttered one of those classic parental refrains, “Paul, you need to tell me these things the night before.”

Perceiving this as my reluctance to help him, Paul said, “Please, Mom, I won’t pass my competency if I don’t have the clothes.”

Naturally I got them together. Then, while Paul was at the front door watching for the bus, it dawned on me I had forgotten to pack his lunch. Knowing I was cutting it close, I dashed into the kitchen to pull something together. Jerry entered the kitchen, stood there for several minutes watching me as I flew around, making the lunch.

I said, “Do you think I’ll make it in time?”

He said, “No . . . because the bus already came and Paul left.”

I didn’t say anything more.

*

BY AND LARGE, with some exceptions, Keely was spared the personal attacks. Maybe this was because she was as close to a perfect kid as you could get but, more likely, I think she was spared because she was a girl. While I knew she paid a dear price for his antics at home, I appreciated the void he was able to fill in her life even though, through no fault of hers, it contributed to the trap I was in.

Later on, I came to understand that my husband’s behavior had nothing to do with me. The fact is, he wanted to dominate and control me and thus created an oppressive environment with verbal abuse as his greatest weapon. I learned too that the pain of verbal abuse is as great as physical abuse, but in some ways more insidious because it’s hidden and the perpetrator routinely denies it. And while he inflicted unnecessary pain, he did not destroy my sense of self. Maybe it’s because I didn’t crumble that he picked on the most vulnerable among us, as bullies do, knowing too that Paul was my Achilles Heel.

While I have avoided revealing the most egregious incidents, these challenges were part of the reality of our journey and significant in Paul’s development. The fact is, my shame in having made this choice, and then tolerating the circumstances, trumps any remote temptation to cast aspersions on an individual who is long gone from our lives. Unable to change the past, and fully acknowledging my own failing, I can only hope to help others who may find themselves in a similar trap and for whom my insight may have some value. So often, when in the midst of difficult times, we can’t see the way out.

When a therapist asked me why I stayed, I gave it a lot of thought. Naturally, it was complicated. One thing I realized—beyond my trying to make it work, hoping it would get better, not wanting to give up—was the degree of turmoil in my life that depleted the sort of reserves needed to take on disruption. Also, the children did benefit from my husband’s good qualities. He taught Keely to ride a bike and to love opera and taught Paul to ski, something they did together every year.

Paul’s few friends, outside the network provided by our family and friends, lived far and wide, and Jerry thought nothing of giving up a Saturday to drive to Leonardtown and back, for example, so that Paul could have a playdate. While they loved their biological father, his presence in their lives fluctuated, and they clamored for what children need most—time. And as they lapped up the attention their stepfather did offer, they learned to turn a blind eye to his hurtful behavior. And lastly, I would have been embarrassed within the community we shared, even though I’m now ashamed to admit that “appearances” could have kept me from doing what I knew in my heart was right for me.

The fact is, during these years, my children did not have a predictable home life or an environment in which adult wisdom and dignity were the norm, making me all the more grateful for the grandparents and aunts and uncles whose stability was reliable.

I alone brought this into our world. It is among my greatest regrets.