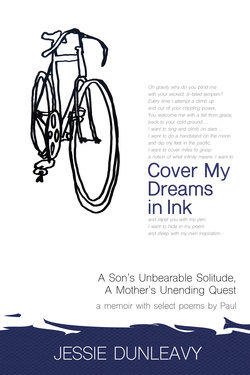

Читать книгу Cover My Dreams in Ink: A Son's Unbearable Solitude, A Mother's Unending Quest - Jessie Dunleavy - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 5

Craving Connection

Then there’s my heart that craves

Mostly connection

And a good deal of rest

In between conversations

So that I can be recharged

And ready to talk again.

My life… It means everything

That I get the chance to connect

I don’t know how else to put this into words

I’d give you a hug but my hands,

They’re behind my back.

I WAS WORRIED. Paul was making progress, but he needed a peer group. He continued to be sweet and good-natured, but he needed a place to belong. It was 1995. Paul would be entering seventh grade, and his pending adolescence ramped up my sense of urgency. I was determined to get him in a school where he would thrive—and stay! A school that would recognize his strengths and engage him. A school that knew how to accommodate his unique challenges.

I feared his being underestimated as much as I did his being overwhelmed. Or worse yet, overlooked.

Of all the schools I came to know, The Lab School continued to be my favorite. Designed for children with language-based learning disabilities, it stood out as a place that could inspire and support Paul. When I visited there, I saw creative teaching that didn’t short-change intellectual development and a broad curriculum intertwined with the arts. Without question, it was a place that wanted kids to blossom more than it wanted to keep them in line. And, at the risk of sounding corny, it spoke to me; I just knew it would make a big difference for Paul. It was my dream.

The school was located in Northwest Washington, D.C., a good hour from our house, which, as Paul got older, seemed more reasonable. When we’d applied there before, it was late in the season, and spaces for new students were hard to come by. During Paul’s year of homeschooling, his application for seventh grade was submitted on time to Lab and a couple of other approved schools.

To give Paul a fighting chance, attention to his medical needs in light of his deficits was a top priority. Even though it was tempting to leave well-enough alone, I wasn’t prepared to settle. I knew we needed to keep pursuing the right therapy, one prong of which was medication management.

During Paul’s year of homeschooling, we had experimented by substituting the combination of Prozac and Dexedrine in place of the imipramine, something more doctors were finding a good option at the time for hard-to-medicate attentional issues. Even though imipramine had proved to be most effective in helping Paul pay attention, it was prescribed with caution due to its risk of cardiac arrhythmia—irregular heartbeat. Routine EKG tests monitored this risk for Paul but, if the combination of medications could provide the same benefit, the absence of risk would make it preferable. If not, we would double back. Even without a school setting that year, it became clear to me that the imipramine was more beneficial for Paul and I was in favor of resuming it.

I wished Paul could have been easily characterized and summarized, condensed on paper with standardized testing results and conventional school records. But this would never be. Test scores were all over the road, and most often reflected glaring weaknesses. As we’d known for years, test results for Paul revealed his performance on the test, not his ability. Paul had significant deficits, without question, but test scores in isolation simply didn’t align in a way that provided a road map for his programmatic needs. It was anecdotal information from firsthand experiences with Paul—tapping into his thought process and the ways he interpreted meaning—that provided an understanding of his depth, his sensitivity, and his interest in learning.

I always thought Paul’s intuition and his emotional intelligence were strengths. Every teacher Paul ever worked with had emphasized his remarkable capacity for empathy and compassion. When Paul was barely six years old, he asked me, “Do you like going to work?”

My answer, “Yes, I do,” apparently didn’t satisfy him.

“But how do you feel when you get there? Do you feel happy? I mean, when you walk in the door, how do you feel?”

Around this same age, we went to New York City for several days during a school break. Just after we hopped in the back of a cab, Paul looked at the driver, then turned to me. In a decibel I would’ve reserved for announcing an imminent safety threat, Paul asked, “Is he happy?”

Trying to soothe his concerns without involving the cab driver in our conversation, I quietly replied, “Yes, I imagine he’s happy.”

As Paul continued to look at me, I knew my credibility was tanking—by no means a first.

He then matter-of-factly said, “He doesn’t look happy.”

A day or so later, we headed out for sightseeing and dinner. As we waited to cross 57th Street, we saw two homeless men sitting on a sidewalk grate. Bearing in mind the fact Paul was still worried about the cab driver, one can imagine the number of questions this sighting inspired. When Paul wasn’t hungry for his dinner that evening, I didn’t think too much about it until he asked for a doggie bag. Then I knew what was coming. As we headed back to the hotel, he asked that we retrace our steps. No words were spoken, but Paul delivered his dinner to the two men.

We went to Disney World when Paul was twelve and Keely fifteen. Paul loved everything about the experience and at the end bought a picture book he actually slept with for weeks. As we were driving home from the airport, and Paul was looking through the book for the thousandth time, he asked me, “Was that trip expensive?”

I frankly don’t remember my explanation, but I do remember saying, “Why do you ask?”

Paul replied, “I just want to make sure I can do the same thing for my children.”

I could write pages about Calvin and Hobbes—his beloved gerbils—and Ruff-Ruff—a stuffed dog Paul loved like a human and made things for—a house, clothing, and, I’m not kidding, a baby book. Don’t you know when I cleaned out Paul’s apartment, I found Ruff-Ruff at the bottom of a trunk Paul had moved from place to place over the years, wrapped in a baby blanket Paul also had saved for sentimental reasons.

Just a couple of years ago, Paul told me he had seen the movie Twelve Years a Slave. In recounting part of the story, he started to weep, which I could tell caught him off guard. Even so, he continued telling me about it through his tears. “All she wanted was soap, Mom. She was beaten because she used a little piece of soap. I don’t think you should see it. It’s just too sad.”

In addition to Paul’s genuine concern for others, he was insightful. Because his social cueing was an area of weakness, he was often isolated in a group situation. But he would later report to me what he took in about others. He spotted the disingenuous with remarkable accuracy as he did those who were truly kind.

He just read people. And he amused me with his reports. Recently, he asked me, “You know that friend of yours who walks her dog in the neighborhood?” I answered, “Elizabeth? Donna?” He said, “I think, Elizabeth . . . Well, anyway, she worries about me.”

“That doesn’t surprise me either way, both are sweet people and my friends, so it stands to reason.” I said. “But how do you know?” I asked. “She just does.” I, of course, knew my friends were concerned for his well-being and somehow Paul knew it too.

I learned to rely on Paul’s intuitive gifts. I also came to know that the disabled are often more keenly aware of authentic kindness for the simple reason that one can indeed judge the character of a person by how he treats those who can do nothing for him. When Paul said someone was kind, I knew every single time that he was right. He was well wired to assess the difference between acting nice and being kind.

*

PAUL WAS ALSO a creative thinker and benefitted from teachers who recognized this and stimulated him to think more deeply. A recent reminder came to me in a sympathy letter from Paul’s homeschool teacher, Gretchen Nyland:

%%%

May 2017

Dear Jessie,

%%%

I cannot hope to “alleviate, assuage, take away, appease, soothe, allay, mitigate, ease, lessen, soften” your grief. This was our method—Paulie’s and mine—to think of all the ways we could express one thought and then end up in the dictionary amazed at how many more ways there were.

%%%

He shared with me a good year of his young life. One that I’ve always cherished. Perhaps because it was one on one—and our attention was always with each other for those hours each day.

%%%

I can’t imagine your grief for losing Paulie. I can only hope it will subside, abate, lower (“Not as many good words here,” Paulie would have informed you.)

%%%

It is probably hard to smile right now, but it will come back as you remember the goodness of his life, for he was a good, gentle person—gone too soon.

%%%

I’m sad, but smiling in thinking about him.

%%%

Much love,

Gretchen

%%%

In thinking about the school situation, I knew we were fortunate to have Paul’s homeschool teachers as references. They all loved him, and knew him well, which I figured would help us live down the regrettable circumstances that had tainted his applications the year before.

When Paul was accepted to the summer session at The Lab School, I was thrilled! It was a very good sign, I thought. They would have time to get to know him, and there was no doubt they would love him. Everyone did. The summer session ran from late June through mid-August, and Paul’s medication changeover began in early June. Knowing that the transition period would be hard for Paul, I was eager to get it behind us and was focused on realizing its benefits in time for his Lab School classes.

To reach the optimal dosage of 100 mg of imipramine per day, the plan was to start with 50 mg and, after obtaining EKG results and consulting with Dr. Roberts, to increase the dosage by 10 mg—with this pattern repeating every four days. I had this sequence mapped out on a calendar and felt confident about the time frame. If I was efficient in getting the EKG tests, we would be in good shape.

What I didn’t anticipate was the lag time between submitting the lab test results and Dr. Roberts returning my calls and sanctioning the increased dosage. As we stalled in the changeover process, I could see that Paul wasn’t functioning as well as he did on a full dosage of either medication regimen, and I deeply regretted making this change during this critical time.

Apparently, my voicemail messages—pleading our case—fell on deaf ears. And the excruciating delay in response from the doctor at every possible turn landed us in the last quarter of the summer program before the medication changeover was complete, at which time, as we had expected, Paul began to function at his best. This was heartening, for sure, but was it too late for him to demonstrate his strengths in a setting where he had little time remaining? And where he had not been himself for the first four or five weeks of a six-week program? Needless to say, I was incredibly frustrated, which I lamented to Dr. Watkins more than once during those painful days as I felt my hopes being thwarted yet again.

In spite of the challenges beyond Paul’s control, he enjoyed the summer program, and his feedback to me about his experiences was encouraging. He spoke each day about his friends—Matt, Seth, Kia—and the course work, the field trips, and the projects. He never complained about the ride, left the house cheerfully each day, and began to refer to Lab as “my school.”

In late August, the school notified me that there was not an available space for Paul. I knew the summer program had been a test case for their admission decision and I was beside myself.

Since Paul had come into his own in the home stretch, and I was interested in the school’s perspective and, frankly, still hanging on to a thread of hope, I called the summer program’s lead teacher. I told her about the medication transition. She said she did see Paul becoming more interactive and alert in the final days, as had a couple of other teachers. She suggested I write a letter to the school explaining the details of Paul’s transition, which I did in short order—even jumping at the chance, while knowing in my heart that it was a lost cause and that they were probably sick of me and my letters. Dr. Watkins called the same teacher who told him Paul was never a challenge behaviorally, that he’d endeared the teachers and, if his attentional issues could be better remediated, he would fit within the parameters of the program.

As my hopes steadily plummeted, I began to try to accept the fact that Paul would have to attend Harbour School, a Level V school just outside of Annapolis serving children with multiple handicaps, which I had visited a couple of times and did not feel was right for Paul. My heart was broken, but I had to resign myself to the reality.

I called the county and was astounded to learn they had somehow assumed Paul was enrolled at Lab School for the coming year and, because of this, had passed up a space for Paul at Harbour School, which I foolishly had thought of as a perpetual backup. Nothing more could be done, I was told, until the next ARD meeting, set for mid-September.

Yet again, the first day of school was upon us, and Paul had no place to go.

I was in for another big surprise when, on that first day, a school bus arrived at our house to take Paul to Lab School, representing a detail the county overlooked and one of a string of snafus on the horizon. Was I ever tempted to put him on that bus!

I was upset with the county for the balls dropped. Making matters worse, I was the only one to show up for the scheduled ARD meeting, which then had to be rescheduled for later in the month.

Because Paul was staying home alone while I went to work, even a small delay was painful. When we finally had our ARD meeting, I was offered ten hours per week of homeschooling. I petitioned for more hours, and was prepared to go to battle on that front, when I learned of a space for Paul at Harbour School, where he enrolled as of November.

As far as Paul knew, I was delighted with the placement and, as always, I formed good relationships with the teachers. Paul complained about the school, but I told him to look for the good. He did make a new friend, another Scott, a boy whose love for playing the guitar matched Paul’s and led to them forming a band with another boy in Scott’s neighborhood in Laurel, Maryland. While Paul liked saying he was in a band, practices were limited by the distance between the boys, and they didn’t exactly have any gigs lined up. But I do remember them performing once at school and another time in a line-up of other bands, an opportunity kindly arranged by Paul’s guitar teacher. Despite Paul’s challenges, he was innately musical, and these experiences for him warmed my heart.

Often I was asked if Paul’s disability had a specific label. Was it merely Attention Deficit Disorder? Or, maybe, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder? But the fact is, Paul never fit a precise description of any one diagnosis. I remembered Dr. Denckla had said, “ADD with other neurological involvement.” Considering Paul was not hyperactive, maybe ADD was most fitting. But I knew it was more than that.

Dr. Hyde, the neurologist Paul had seen when he was eleven, said Paul had elements of Pervasive Development Disorder and that his episodes of unresponsiveness likely represented an abnormality related to an underlying disorder of the central nervous system. Years later, I would come to think Paul was on the autism spectrum, as Pervasive Development Disorder suggests. No matter what, I knew it wasn’t the label, but the treatment, that mattered.