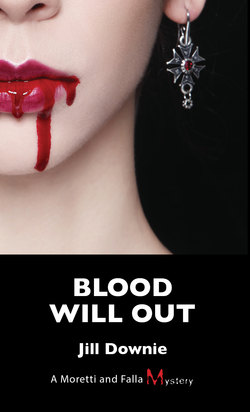

Читать книгу Blood Will Out - Jill Downie - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеDeath of a Hermit

No horizon today. The mist gathered close to the land, touching the headland to the west of Rocquaine Bay and hiding the long sandy sweep of the western coastline from view. Certainly from his view. Of all the lost properties of youth, the one he most regretted was his marvellous vision. Cataracts, he supposed. Fixable, he knew that, but it would mean contact. He would think about it when the game became worth the candle and he could no longer read.

The tide was on the rise, but there was still an expanse of bare silver-grey sand, jotted with the red, brown and green of lichen-covered rocks, trails of seaweed, the vraic he had gathered with his father in the dim, distant past, when the world was young, at the first new moon after Candlemas, and then again in midsummer. He could still remember the sharpness of its smell in his nostrils, burning in the hearth, the ashes rich with potash to feed the soil.

He scrambled back from the beach over the rocks at the end of the high wall that protected the road against the high spring tides, something that became increasingly difficult with every passing day. Then he made his way past the Imperial Hotel and along the headland over Portelet Harbour, stopping briefly at the Table des Pions to pay his respects. A fairy ring long before it was used as a resting place by the soldiers of the local seigneurs on their chevauchées around the island parishes, it was a good place for him also to draw breath and courage before the hardest part of his climb, up towards Pleinmont Naval Observation Tower. Built by the Germans during the occupation of the island, deserted for years, it was now reconstructed for the tourists and, thankfully, open only two afternoons a week to disturb the quiet of the headland. Like the fairy ring, it too was haunted, and some of the presences were familiar to him.

After that, it was an easy walk across the Common, to the home he had built for himself. He was not the first solitary to have lived there, and he wondered if he would be the last. Probably so. Well-meaning and not so well-meaning individuals were constantly threatening his solitude and his peace of mind.

Home. He had built it like an Iron-Age roundhouse, and thatched the roof low over the only window. The walls had not been a problem, because he had learned about bricklaying from his father, who had built houses and worked in the granite quarries at St. Sampson. The roof had been a challenge, but he was determined not to use modern tiles. Finally, he had used a combination of turf and thatch, and compromised by lining the interior with batts of pink fibreglass insulation, covered in thick plastic as a moisture barrier. It gave a pleasant rosy glow to the place he called home, particularly in the light of his oil lamp, when the storms blew in across the Hanways and the Hanois Lighthouse wailed. Unlike the Iron-Age denizens of such a structure, he had not made a hole in the centre of the roof for the smoke to escape, but had added a chimney for his fireplace, keeping the thatch and turf well away from it.

He walked around to the door he had installed on the inland-facing wall, the one most protected from the prevailing wind. He never locked it, because less damage was done if the curious and the tearaways could get inside. Nothing of interest for the average thief, anyway: no stereos or televisions, no modern appliances. An intruder once made off with his camp stove, but had abandoned it in some bushes a few feet away. Not worth the effort, presumably. He raised the latch and let himself in.

This time, someone was waiting for him.

“I wondered when you would come,” he said. “I knew you would come, eventually.”

He felt a strange sense of relief, like a burden lifted. The other shoe finally dropping.