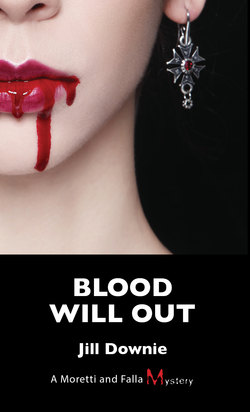

Читать книгу Blood Will Out - Jill Downie - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

ОглавлениеElodie Ashton bent down to pick up the secateurs she had dropped when she opened the door into the garden, and felt a twinge. The damp of approaching autumn was getting to her, and she had forgotten to put the nutmeg in the pocket of her gardening trousers.

Damn. She was far too young for this, she thought, both sore hips and superstitions. But better a nutmeg in her pocket than a needle in her trochanter, as had been suggested by Doctor Clarke.

“Too much sitting in front of a computer,” he said.

“Is that your expert medical diagnosis?”

“Actually, yes. You’re getting to an age where it’s going to catch up with you, and you’ll get fat.”

“Don’t beat around the bush, will you?”

The elderberry bush near the back door of the cottage was loaded with berries, and Elodie was determined to get to them before the wood pigeons and the blackbirds this year. The year before she had been on the mainland at a conference, and had missed the height of the season. As she reached up to cut a particularly luscious branch, she heard the sound of a car turning into her driveway.

Damn again. A voice calling out. Not damn. This voice was always welcome. Her goddaughter, Liz.

“I’m in the garden — come around!”

Detective Sergeant Liz Falla was off duty, wearing comfortable jeans and a black leather jacket. Her open-toed sandals revealed scarlet nails, and she was wearing large golden hoops in her ears. When she smiled, her resemblance to her father was striking, Elodie had often thought, but that was about all Liz had in common with her father — that, and a physical resemblance to those ancient Norman roots.

If, that is, the name Falla was indeed Norman, but it probably was. The theory that some poor Spanish wretch washed up in Guernsey when the Armada was blown off course in stormy waters, and stayed to reproduce, was unlikely, and the romantic possibility of being descended from fifteenth-century Jewish nobility fleeing Spain to escape persecution difficult to prove.

The rest of Liz was pure Ashton. She had her mother’s singing voice, and the Ashton combination of an analytical mind and an intuitive grasp of circumstance and situation. Who knew what that big sister of hers could have done with her life, Elodie had often wondered, if she had not fallen in love with Dan Falla and had Liz when she was just out of her teens. But Joan Falla seemed a happy woman, and had achieved what her little sister had not. Love and marriage. More precisely, a marriage that worked.

Elodie. Such a fancy name, an unlikely choice for her commonsense mother.

“Why?” she had asked.

“Your father’s choice. Joan was my choice for your sister,” was her mother’s reply. And there the matter had rested.

“What are you doing around here?” Elodie asked, putting down the basket and hugging Liz.

“I’m on my way to work out at Beau Sejour Recreation Centre, and I left a little early so I could drop in and see you. Easy to do, now that I finally have wheels. Come out and let me show them off to you.”

One of the unexpected bonuses of the last case Liz had worked on had been the gift of some vintage French couture. After checking with Chief Officer Hanley that accepting it was in order, about which he had been satisfactorily vague, she had promptly sold it on eBay and bought herself a car. Or at least made a substantial downpayment on a pretty little Figaro in pale aqua, a so-called “retro car,” made by Nissan. Second-hand, but still … air-conditioning, leather interior in a soft cream colour — and a roof that opened. The stuff of dreams, now made reality.

Elodie’s reaction was gratifyingly enthusiastic. “It’s so … you, Liz. The perfect accessory!”

“I’ve always envied my Guvnor his Triumph, and I can’t wait to show him.” Together they walked back into the house.

“I thought I’d find you at the computer,” Liz said, “working your magic for some verbally challenged mainland medico.”

“Well, I’m working magic, but on my elderberry tree. Give me a hand. You can reach some of the higher branches for me before you go.”

“Ah, come on, El. Not you too!” Liz protested. “Can’t you just trust it to keep the witches away from your kitchen door without mumbling incantations over it?”

“It’s doing a good job of that for me, all on its own. Haven’t seen a witch in these parts, ever.” Elodie chuckled and held out the secateurs to Liz. “I know how you feel about Aunt Becky, but this is Bacchic magic — sort of. My witches’ brew is going to be a really potent elderberry-flavoured vodka. Come on, and I’ll show you how to make a diabolically delicious potion,” she said, pointing to a berry-laden branch near the top of the tree.

As they worked together, talking idly about this and that, Liz Falla thought to herself, not for the first time, what a puzzle this woman was. It was not so much that she had followed a different path from Liz’s mother, Elodie’s older sister — much older sister — but that she had opted for a career so far removed from people. She held the best parties, belonged to the Island Players and enjoyed appearing on stage from time to time, but spent her working career before a computer screen.

Elodie said little to her family about her professional life, largely because of the esoteric and specialized nature of what she did, so Liz had looked her up and found her website. On it, she described herself as a medical researcher, editor and illustrator, and the examples she provided of her work were impressive. They varied from working with academic presses and editing specific research projects to composing speeches.

Elodie also said little about her personal life in London before she came back to Guernsey, but Joan Falla was sure there was heartbreak in her sister’s past.

“She was divorced, Mum. That’s heartbreak,” Liz had responded.

“That’s not what I mean,” her mother had enigmatically replied.

If she had decided to hole up back home in Guernsey to escape from whatever troubles she’d experienced, Elodie could not hide her good looks. Even in her working gear of patched jeans and a loose-fitting green silk blouse that had seen better days, she was striking. From some distant Teutonic ancestor she had inherited curly red hair and the ivory skin of the redhead, but without freckles.

“I wish I’d inherited the tall gene that you and my sister got from somewhere.”

“You are petite, Elodie.”

“I am short. That’s what I always say to your mother, and this is when I’d give a witch’s incantation for a few extra inches.”

Liz grinned. “I must say, it’s useful in my job to have my mother’s extra inches.” She reached up and pulled down another branch. The basket was just about full.

“Why? Because you are as tall as the bad guys?

“Because I am just about as tall as the good guys. Great to look my fellow officers in the eye and say ‘get lost’ when necessary.”

“Like that, is it?”

“Only sometimes. This looks like plenty — how much booze are you planning to make?”

“Liqueur, please. Yup, that’s enough. Do you have time for a coffee?”

“And to see what you do with these little suckers. Time for both brews. It was a rough morning, which is why I’m on my way to Beau Sejour, to work it out of my system.”

“Want to tell me? Or can you?”

Liz shrugged her shoulders. “I don’t see why not. You know the old hermit who lives in that weird place near Rocquaine Bay? He topped himself.”

The flippant tone did not surprise Elodie. She had heard it before in similar situations, or during family discussions. It drove her sister to distraction, but she knew it was her niece’s way of coping — not just with her job — but with other people’s anger, or pain. Or her own.

“Poor old fellow. Who found him?”

“The postman, believe it or not. Delivering magazines.”

Elodie watched as Liz walked towards the kitchen door, then appeared to change her mind. She took a few steps down the path that led to the row of chestnut trees that separated her cottage from the garden behind her. The grass on each side of the path was scattered with windfalls from the apple trees, and soon the prickly cases of the chestnuts would join them.

“Looking for conkers? A bit early yet,” she called out.

“There are going to be some beauts. Pity you weren’t here when I was a kid.”

“To me, you’re still a kid.” Elodie laughed. She paused, then asked, “So, no more about the hermit?”

Liz did not respond immediately, and when she did her voice was serious, flippancy gone.

“What do you know about your neighbour, the one who is renting Brenda Le Huray’s place? The property that backs on to yours?”

Elodie came down the path and joined her niece. “Brenda moved in with her daughter, and I don’t really miss her. She was always complaining about the chestnut trees. ‘Messy,’ she called them. His name is Hugo Shawcross and he’s a folklorist, he tells me, a researcher, and certainly the Internet confirms that. He’s the author of a number of books on the subject.”

“You’ve met him?”

An early conker fell from one of the trees, and Liz picked it up. It lay in the palm of her hand still in its case, like a tiny hedgehog with greenish bristles.

“Yes.” Elodie turned and looked at her niece. “This is not just idle curiosity, is it?”

“No.” Liz gently returned the chestnut-hedgehog to the ground. “Let’s have that coffee and make your potion.” They started back towards the house.

“What do you think of him?” Liz had dropped her voice.

Elodie picked up the basket they had left by the door and shrugged her shoulders. “A bit too chatty for my liking. But he seems pleasant enough, certainly non-threatening.”

Liz held the door as her aunt went in with the basket, and put it on the kitchen table. Elodie had made many changes in the early-eighteenth-century cottage, but, apart from its modern appliances, the kitchen was very much as it had been when its original owners roasted their beef and mutton on the spit over the giant fireplace. She knew how lucky she had been when the cottage had come onto the “open” market. Once you had left the island, it was difficult to get back as a homeowner, because of the protective property laws.

And the other piece of luck was a colossal divorce settlement. Every cloud, as they say. It had certainly helped when it came to putting in a bedroom and bathroom beneath the roof in what had been a loft, and taking out some of the interior walls downstairs to open up the space. She had replaced the white trim around the windows, put in a flagged driveway for her car, keeping the old limestone gateposts marking the edge of the property, and retiled the sloping roof in softly glazed coral-pink terra cotta tiles. Then, having taken care of the personal, she had had the whole place rewired to accommodate her professional working life.

“So, this is by way of being an official call?”

Liz laughed, took off her leather jacket and hung it over the back of a chair. “Not official, no. We’ve had a complaint about him, and since my boss has been off the island, I was asked to look into it. Discreetly.”

“Discreetly?”

Elodie was transferring three large Mason jars to the worn pine surface of the sizeable table that stretched across the centre of the kitchen. She fetched a bottle of vodka from the equally sizeable sideboard, and some chopped-up lemon rind.

“Is he anything I should worry about? Here,” Elodie pointed to a large crockery bowl high on a shelf near the fireplace, “get that down for me, would you?”

Liz obliged. “I don’t think so, and the complaint is so bizarre it could be that we should be looking into the complainer rather than your new neighbour.”

She pulled out a branch of berries from the basket, holding them up against the light, admiring their purple translucence in the sunlight streaming through the window. “Now what do we do?”

Elodie took another branch from the basket. “We’ll need something for the stems and so on. They are mildly toxic. We’ll use this.” She pulled out a plastic pail from under the table, then a tall stool. “You’ll be fine with a chair, but this suits me better.

“So, tell me — is he a flasher? A con artist?” She hopped up on to the stool, and started to pull off the berries, her fingers swiftly turning purple.

“Nothing so run-of-the-mill, El.”

Liz hesitated. It had all sounded so ridiculous this morning, and she couldn’t believe Chief Officer Hanley had asked her to look into it. But he had, and she knew why. Because the complainant was the wife of one of the major estate agents on the island, a man not to be trifled with. It was a familiar theme. She watched the juices trickle over her hands and thought of Lady Macbeth, and blood, and said, “We have been told he is a vampire.”

The shriek of laughter that burst out of Elodie shook the stool on which she was sitting, and she grasped the edge of the table to steady herself.

“Liz, Liz — which demented islander told you that? I cannot believe you are taking this seriously.”

“I’m not, and it certainly added a little light relief to my morning. But Elton Maxwell’s wife does.”

“Ah. So the chief officer does.” Elodie pulled out another branch of berries, and winked across the table at Liz.

“Got it in one. Mrs. Maxwell’s a member of the Island Players. Do you know her?”

“Only as a fellow player. I don’t socialize much with the Maxwells.” Elodie leaned across the table. “Tell me more. Should I be avoiding the garden after dusk? Carrying garlic? Is she out of her tiny mind? If she has one at all?”

Liz shrugged her shoulders and went on picking berries from the stem in her hand. “She’s not quite as wacky as that makes her sound, actually. She says he is writing a play for the group — do you know anything about that?’

“No. But then, I’m only just coming up for air after finishing a really tough project for a researcher at Great Ormond Street Hospital. What does playwriting have to do with vampires?”

“Everything. That’s what the play is about, and what has upset Mrs. Maxwell is that Hugo Shawcross says it is an area of interest to him, because he is a vampire himself, descended from a long line of the undead. She says he is trying to create a splinter group within the Island Players, and has joked about secret oaths and blood sacrifices.”

“Seriously?” Elodie had stopped working on her branch of elderberries, and now looked concerned. “I know they were hoping to get some new blood into the group — sorry, terrible choice of expression — and wanted to attract a younger crowd. But this doesn’t sound like a good idea.”

“No, and that was one of her complaints. That he is a bad influence on the island young. She also said he became threatening when challenged. Mind you, it could be that Mrs. Maxwell doesn’t have much of a sense of humour. He told her to leave him alone or one dark night she’d wake up to find him chomping down on her. Or words to that effect.”

“Yuk. Not nice.” She caught Liz’s eye, and giggled. “Sorry again, Liz, but this is just ridiculous. Does chomping down on someone’s neck constitute a death threat?”

Liz grinned. “Don’t feel the need to apologize. You should hear the jokes back at the office — well, you shouldn’t. Some are just filthy. Even Chief Officer Hanley had difficulty keeping a straight face when he told me, and he’s not a laugh-a-minute kind of feller.”

“Were you planning on going round to talk to him? Do you need backup? We could take some of that.” Elodie pointed to the string of garlic hanging near a thick rope of onions. “I don’t have any crucifixes handy, I’m afraid.”

“I sort of need backup — at least, that is what I was going to ask you.” Liz was no longer looking amused. “But I am now rethinking that, in case this guy is —”

“Dangerous? Have you seen him? He’s not much taller than me, looks more like Gandalf than a vampire, and I’m pretty sure I could take him if I had to.” Elodie got up and went over to the sink to wash her hands. “See, Liz, I don’t believe in fairies, or ghosts, or vampires. But I do think he could be trouble. The Island Players have always played second fiddle to GADOC, and I’m sure that’s what this is about.”

GADOC, the Guernsey Amateur Dramatic and Operatic Society, were the principal group on the island, with a history that went back close to a century. They performed at the well-equipped theatre in the Beau Sejour centre; the Island Players had come into being with a mandate to perform more challenging material. Their audiences, not surprisingly, were considerably smaller, and they were constantly in need of funds.

Elodie went on. “The Players may be hoping that something shocking will help membership. I can always just ask about the play — say I’ve heard about it. I often see him out in his garden, through the trees.”

Elodie turned around and grabbed at a towel near the sink. “Let’s get these beauties into the vodka with the lemon peel.”

Liz went over to the sink, taking the towel from Elodie. Something fragrant was cooking in the oven, and the aroma drifted towards her as she washed her hands.

“There’s a fantastic smell over here. What is it?”

“Lamb shanks, cooking very slowly, with red wine and herbs from the garden. And garlic, of course! Some time you must let me teach you how to cook, young woman. Living on omelettes, fish and chips, and Dwight’s curries — delicious though they are, and I have some in the freezer — is not good. It’ll catch up with you, sooner or later.”

“Knock it off, El. You sound like my mother. Anyway, are lamb shanks a health food?”

“Kind of. They are good for the soul.”

Together they filled the Mason jars, fastening down the lids, and Elodie put on the coffee. “How is Dwight?” she asked. “Still playing in that jazz group with your boss?”

“Yes. He’s fine. We are not an item anymore, you know.”

“I know.” Elodie had her back to Liz, but could hear the subtle change in her voice. She took down two coffee mugs from the shelf near the fireplace and put them on the table. “Is that something you care about, or am I misinterpreting that change of key I hear?”

Liz grinned, and said, “Major to minor you mean? Actually, that’s more about my Guvnor than about Dwight. Thanks.” She took the filled coffee mug, sat down and took a sip. “He was going to come and hear me sing with my group, Jenemie. Then he had to go to London for a debriefing for this last caper — case — of ours and missed it. I was disappointed, don’t know why.”

Elodie looked at her niece, and felt a wave of tenderness. She was younger than her age in some ways, flitting from relationship to relationship, some of them from which she disentangled herself — or was disentangled. Her apparent insouciance about such things was not always genuine, her flippancy a useful cover for hurt.

“Have you heard him play? I have, once. He’s good. Went with your Uncle Vern.” She smiled. “Do you think your disappointment is artistic, or personal? Do you fancy him? He has a certain je ne sais quoi. Well, I do sais quoi. He’s rather gorgeous.”

Liz looked as shocked as if her aunt had made a deeply improper suggestion. “El, please, he’s old enough to be my father. Besides, he’s my boss.” She took a deep draught of her coffee, pushing away the thought of an earlier attraction, a man old enough to be her grandfather.

“Artistic then, I’ll take your word for it. Perhaps he doesn’t want to blur the line between business and pleasure. It can be a dangerous one to cross,” Elodie’s voice hardened, but she did not elaborate, instead adding, “and your piano-playing Guv is not that old, kid. Have you been to the Grand Saracen, the club where he plays?”

“No, only to the restaurant upstairs. Emidio’s. It used to be his father’s. His mum was a Guernsey girl.”

“A wartime romance with an Italian slave labourer, Vern told me. Tell you what, we’ll go together some time. Looks like an ascetic, your Guvnor, but having watched him play, I doubt he is. A lot of smouldering going on beneath that detached exterior. Are you on duty after your workout? Why don’t you come back here and share the lamb shanks with me? If you’re free, that is.”

“Love to. I’ll eat and take notes. Are they easy to make?”

“A doddle. You can use that slow cooker I gave you and give your microwave a break. And I may have some info for you by then. Gandalf usually takes the air around the witching hour, and I’ll stroll down in that direction and engage him in conversation.”

“Okay, but be careful.” Liz stood up and took her jacket off the back of the chair. “You may not believe in fairies or ghosts or vampires, El, but that doesn’t mean Shawcross is a pussycat.”

“He has one — a pussycat, I mean. I hear him calling it. Stoker.” The two women looked at each other, and Elodie said, “First name probably Bram, don’t you think?”

She laughed, but Liz didn’t. Elodie went over to the sink and fetched a damp cloth, came back and started to wipe the jars. She looked across the table at her niece, her voice now deadly serious. “I may not believe in vampires, Liz, but that doesn’t mean I don’t believe in wickedness, and depravity and vice. I think there is as much evil in this world as good. Possibly more.”

Liz looked at her aunt, startled at this sudden outpouring of hidden emotion, as if she had returned to some dark episode in her life, and Liz thought of her mother’s enigmatic comment on her sister’s past.

“But I don’t have to tell you that, in your job,” she added and changed the subject. “Is your boss still in London?”

“No, actually, he’s taken a couple of days off.” Liz pulled her car keys out of her pocket and added, “At this moment he’s probably messing about in his new boat.”

Ed Moretti was thinking of his father. Not being a Guernseyman, Emidio Moretti had felt no particular desire to own a boat, although he had talked about it from time to time. So Moretti had got his knowledge and his experience from his mother’s brother, who owned a boat and was only too happy to have a strong young boy as his crew. He looked across the deck of his new Westerly Centaur at his own crew, who was at that moment leaning rather perilously over the side of the boat.

Don Taylor was no young boy, but a man in his mid-forties with the string-bean build and the stamina of a long-distance runner. On an island measuring just over twenty-four square miles, he still managed to keep up his passion on the extensive network of cliff paths. He worked with the Financial Services Commission, one of the elements in the complex structure involved with the financial scene, now the island’s main source of income. Moretti had worked together with Don once before, and Don had provided a key piece of information on Moretti’s last case.

“Good decision to get a bilge-keeler with the tides around these parts.” Don’s voice drifted back on the wind to Moretti. “And you won’t lose much except to windward. You’ll not always be diesel-powered, I trust.”

“I wouldn’t dare, not with you on board, but I wanted to give the motor another good outing while I was still able to get my money back.”

Moretti looked up at the cliffs and felt happiness flooding him. Well, contentment anyway. The kind of escape and freedom he felt at the Grand Saracen, or playing the piano that had been his mother’s, in the house that had been his childhood home. Beyond the treacherous rocks around Icart Point, he could see the coast beginning to curve inwards to Moulin Huet Bay, and out again to the Pea Stacks, three great rock masses on the southeast tip of the coastline, Le Petit Aiguillon, le Gros Aiguillon, and l’Aiguillon d’Andrelot, painted by Renoir when he visited the island. Midnight assassins, Victor Hugo had called them.

L’Aiguillon d’Andrelot was also known as Le Petit Bonhomme Andriou, and was supposed to resemble a monk in his cowl and gown. Passing fishermen tipped their caps to him, or offered small sacrifices — a libation, a biscuit, even a garment. Or so Moretti was told by Les De Putron, who had laughed at the old superstition and then doffed his cap as they sailed past.

“Better safe than sorry,” he said. “Mind you do the same. Be on the safe side,” he repeated.

Looking at the massive rocks, Moretti wondered at the power of superstition. An old observation post used by the Germans at Fort Grey, once in ruins, was now a shipwreck museum, a monument to the hundreds of lives lost along that hazardous coast. But perhaps they had not made an offering to le petit bonhomme.

The wind had come up, and Moretti concentrated on keeping the Centaur beyond the reefs and shoals of the promontory. Thank God he had done the sensible thing and taken lessons from Les, who ran a small private company running charters, renting boats and giving lessons out of St. Sampson’s harbour.

He had thought at first of keeping the Centaur at Beaucette Marina, on the northeast coast of the island. At one time a granite quarry, blasted into being as a marina in the sixties by British army engineers, it had appealed because of its distance from where he worked, but in the end that told against it. He had a feeling that his boat would spend more time bobbing about with the seals who showed up at Beaucette from time to time, than with him at sea.

The obvious choice of mooring was the harbour in St. Peter Port, and marina rates were the same anywhere, but Moretti still liked the thought of getting outside the capital for a change. He finally settled on St. Sampson’s as being closer to the small garage that looked after his Triumph; he could leave it in the safe hands of Bert Brehaut, the garage owner, when he was sailing. Security for the boats anchored there was good, with a punch-in code for berth holders and boat crews, but he didn’t fancy leaving his roadster outside the solid chain-link fence.

Sometimes he stayed overnight on the boat, which came equipped below decks with a sleeping area that converted into a dinette, complete with small stove, storage, a sink and toilet. It had been a financial stretch, but would save him finding accommodation when he visited the other islands, or France.

“Tide’s up. Want to pull in to Saints Bay and walk over to that little Greek restaurant past Icart Point, near Le Gouffre? Les De Putron has a mooring and a dinghy he keeps there,” he called over to Don.

“Great idea.”

The winds calmed as they approached the small bay, and the choppy water settled into ripples, picture-postcard blue and beautiful. Moretti cut the engine, and they moved gently in to the mooring. A few minutes later, they had pulled the dinghy up on to the dock, and were climbing the steep path to the top of the cliffs, with the natural rock face on one side, and a man-made granite bulwark on the other. Somewhere, an invisible stream made its way to the coast, concealed by vegetation, its waters murmuring unseen.

It was tough going up the cliff path, steep and uneven, a track that had been there for centuries. Don leaped ahead, light and easy on his feet, and turned back to laugh at Moretti.

“Want a hand?”

“You’re a bloody mountain goat, Taylor.”

“That’s what used to use these paths — goats, I mean. Goats and fishermen and smugglers. Watch the wall, my darling, when the gentlemen go by, as the poet says.” Don gestured towards the wall’s granite face.

“Not what I’m supposed to do when they’re bringing in brandy for the parson, or marijuana for — whoever. Not in my job.”

“True. Look at those, running down the side of the cliff. Even I wouldn’t use those.”

Don had reached the top, and was pointing at barely visible tracks down the sheer cliff face to their left.

“Goat tracks. Used to be all kinds. Goats, I mean. Falla, my partner, has an aunt who still keeps goats somewhere around here.”

They turned left and headed towards Icart Point, with the sea and the cliff face close to the footpath. On the other side was St. Martin’s Common, where sheep had roamed free for generations, but they were long gone, like most of the goats that had used the old tracks. Gone also were the côtils, the terraces where smallholders grew potatoes, or planted bulbs for the once-flourishing flower-growing industry.

There was little colour on the cliffs at this time of year, with the heather and gorse past their prime, but the sky was full of gulls wheeling and shrieking overhead in perpetual motion, and the wind carried the sound of the waves, crashing against the rocks, the familiar soundtrack of the coastline. Even up here, the air was flavoured with salt.

“You know what they say about gorse?” The wind was strong enough for Don to have to shout at Moretti. “When the gorse is not in flower, then kissing is out of fashion.”

“And gorse is always in flower. More or less.”

“So the kissing never has to stop. All one requires is the woman to kiss.”

Moretti looked at Don’s face, but he was not laughing. Was this just idle banter, or something more?

The little Greek restaurant was in a tree-filled valley above Le Gouffre, a small anchorage between towering cliffs. The waitress who served them sounded Australian, but the food was Greek. They ordered a range of appetizers and coffee and sat outside, watching a large marmalade cat luxuriate in the late summer sun in this protected valley.

“Sybarites, cats. They certainly know how to seize the day,” said Don, popping an olive into his mouth and chewing with gusto. He had the voracious appetite of the long-distance runner, without a trace of body fat. “Speaking of which, is this your last day of freedom?”

The coffee was good. Hot, strong and black as — as the colour of his ex-lover’s hair. Although Moretti was not sure you could call someone an ex-lover who had, in effect, been a one-night stand. Not that he’d planned it that way.

“It is, then it’s back to the desk, I imagine. Break-ins and burglaries and little else. But maybe I’ll have more time for the boat.”

“And playing at the club with the Fénions? Means layabouts, doesn’t it? Great name for a bunch of jazz musicians — or an outsider’s perception of jazz musicians. Have you got a replacement for your horn player?”

“Nope. And no hopes of one on the horizon. So it’ll be Dwight on drums, Lonnie on bass and me playing piano. Won’t be quite the same.”

“Still, let me know next time you are playing.”

Moretti felt a damp little cloud of depression settle over him, and fingered the lighter he always carried in his pocket. Why a lighter should be the talisman that helped him keep off the noxious weed, he couldn’t imagine. But it was at moments like this he still longed for a smoke.

Don dipped a dolma in tzatziki and swallowed it whole. “God, I love garlic. Just as well I don’t have a woman in my life at the moment. I’ll stink for twenty-four hours after this lot. How about you, Ed? Any new lady in your life?”

Women again. Moretti looked across the table at the man who knew about as much about his private life as anyone, which was virtually nothing. Idle chatter about women interested him about as much as discussing island politics, or what were now called “relationships.” All three topics were minefields, as dangerous as these cliffs had been after the Germans left the island.

“No new lady, but a new man. Should take up about as much of my time as a new lady, and be far less rewarding. You’ve heard of fast-tracking?”

“Taking in graduates and speeding them to the top? Weren’t you one?”

“Yes. APSG — the Police Accelerated Promotion Scheme for Graduates. I’ve got one arriving tomorrow, and my instructions are to take him under my wing.”

“Don’t see you as the mother-hen type.” Don grinned. “Do you know anything about him?”

“Some. He is a Londoner, mid-twenties, has a science degree of some sort. I’ve spoken to him on the phone. Tells me he didn’t want to be a teacher, so decided to be a policeman.”

“Charming. Anything else he shared with you that’s more endearing? What’s his name?”

Moretti bent down to stroke the cat, who had come over to join them rubbing hopefully around his feet. “An interesting one,” he replied, “Aloisio Brown. Mother’s Portuguese. And no, I cannot think of a single aspect of this that’s the least bit endearing.”

He held out a piece of taramasalata to the cat, who took it from him with great delicacy, and ate it.