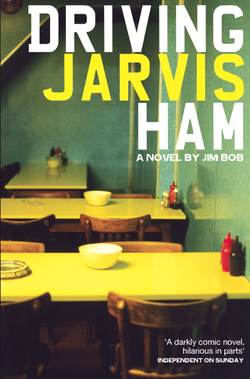

Читать книгу Driving Jarvis Ham - Jim Bob - Страница 8

ОглавлениеThe Ham and Hams Teahouse is one of five shops in a short row of businesses at the top of Fore Street. Inside it looks like an episode of the Antiques Roadshow. None of the furniture matches. The chairs don’t go with the tables; teacups sit uncomfortably on odd saucers. Knives, forks, spoons and sugar tongs all come from different cutlery sets. If it actually had been an episode of the Antiques Roadshow, the expert would have said, ‘If only you had the full set, I think, for insurance purposes, you would have been looking at fifty to a hundred thousand pounds. Unfortunately, what you have here is worth fuck all.’

The Ham and Hams Teahouse didn’t care. Variety was its spice of life. The leaflets on the counter next to the big old Kerching! style till boasted about it: The Ham and Hams Teahouse is not Starbucks, the leaflets proclaimed above a drawing of an impossible cake.

Next to the counter there’s a floor to ceiling glass cabinet that is a shrine to sugar. A cake castle. Half a dozen glass shelves packed with Bakewell tarts and carrot cakes, with sticky date, cream and treacle cakes. Big and high cakes topped with thick cream and fresh strawberries, looking like something the Queen might wear on the top of her head for the State Opening of Parliament. There are pineapple upside down cakes, victoria sponge up the right way cakes and tiramisu to die for. In fact, nut allergy sufferers have been known to play anaphylaxis roulette with a slice of chocolate and hazelnut panforte from the Ham and Hams Teahouse. From up to half a mile away, if you stood very still and quiet, you could hear customers licking their lips and saying ‘yum yum’.

The flag of the day in the postage stamp of lawn in front of the Ham and Hams this morning was the flag of the Cook Islands: a blue background with a Union Jack in the top left hand corner and a circle of white stars to the right. There was hardly any wind and the flag was barely moving. A middle-aged couple dressed in shorts and matching sweatshirts sat beneath a pub umbrella at one of the two tables outside the Ham and Hams, they were eating the fluffiest scrambled eggs you’ve ever seen, served on the toastiest toast of all time. I parked the car and walked towards the teahouse.

I could see Jarvis through the window. He was wearing an apron with a picture of a big fat cartoon plum on it – no comment. He saw me and held up two fingers, he mouthed the words, ‘two minutes’ and carried on serving tea and cakes to the tourists. I stood in the street and waited.

A newly blue-rinsed old lady came out of the hairdressers next door to the Ham and Hams. She smiled and said ‘hello’ in that Devon friendly way that freaks out visitors from London who think it’s some kind of a trick or a hidden camera show stunt. I smiled back.

‘Lovely day for it,’ the blue-rinsed lady said.

It was.

There were no paparazzi outside the Ham and Hams Teahouse this morning. No photographers on stepladders trying to get pictures of Jarvis through the window. Nobody jockeyed and jostled for position shouting ‘Jarvis! Jarvis! Over here!’ There’d be no warning of flash photography on the lunchtime news. Not today. The epileptics had nothing to worry about just yet.

The bell above the door of the Ham and Hams Teahouse tinkled and Jarvis walked out and straight past me like I was invisible. He was still wearing his apron. He headed towards my car. I sighed and aimed the key fob over his head, there was a beep beep and a flash of headlights.

‘Don’t cab me Jarvis,’ I called out after him, and then more to myself, ‘I’m not your chauffeur.’ But he was already halfway into the back seat and closing the door. By the time I reached the car he’d already be snoring. He could fall asleep almost instantly like that, like he had a standby switch.

While Jarvis slept in the back I’d obey the signs and drive him carefully through the village, and as I left the village another sign would thank me for having done so. I’d drive carefully as requested through all the other villages and small towns on the way to the A38 – although I’d ignore the sign as I entered one village that someone had altered with white paint or Tipp-Ex to read PLEASE D I E CAREFULLY. I drove on through Yealmpton and Yealmbridge, Ermington and Modbury, seeing signs along the way for Brixton and Kingston: strangely West Indian sounding names for such very white places.

Turning onto the A38, I’d put my foot down. I could now drive less carefully. Make a mobile phone call, take both hands off the wheel. Open a bag of crisps, read a newspaper, start a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle of the Houses of Parliament.

I’d search for a radio station that wasn’t playing sincere British indie guitar music, but I wouldn’t find one and after going round the FM waveband in circles a few times I’d settle on some local news and an overlong, inaccurate weather forecast. I’d presume the weather forecaster was broadcasting from a windowless basement after travelling to work blindfolded in the back of a van. I could have told him it was actually an average day for the time of year. For any time of year really; some bright sunshine, with occasional Simpsons clouds breaking up the otherwise pant blue sky. When we reached the outskirts of Exeter, just before we drove onto the M5 for the few miles of motorway that would take us to the A30 and the A303, it would rain. The radio weatherman was right there at least.

I’d look in the rear-view mirror at the sleeping Jarvis Ham. His chubby face flattened against the car window, his lips and nose distorted like a boxer captured in slow motion after a massive right hook. I’d try to work out what it was that made me not Jarvis’s chauffeur. I just couldn’t put my driving gloved finger on it. He always sat in the back. On all the many times I’d given him lifts I’d never once heard him call shotgun.

Giving Jarvis this latest lift from the South Hams up to London was going to be a more uncomfortable journey than usual for me, and maybe for him too. Not because the car was rubbish or because the roads were particularly bumpy. Far from it. The gearbox and the tyres were brand-new and the roads beneath them were smooth. The reason for my and perhaps Jarvis’s discomfort was that we both had a secret we’d been keeping from one another. Jarvis’s secret was that he’d been writing a diary. My secret was that I’d been reading it.