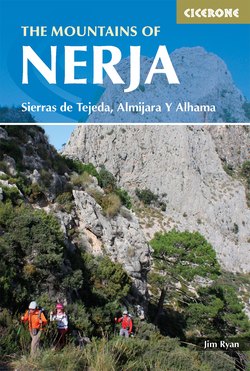

Читать книгу The Mountains of Nerja - Jim Ryan - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The little seaside town of Nerja nestles under a range of mighty mountains that stretch to the north, away from the coast. Hillwalkers internationally have recently begun to realise what treasures lie in this region. Although these mountains are well-known locally in Spain, the neighbouring mountains of the Alpujarras and the Sierra Nevada to the east have up until now been the better recognised attractions for the outdoor fraternity of northern Europe.

However, by 2011, the ever-increasing numbers of visitors coming to the Sierras Tejeda, Almijara and Alhama led the government of Andalucía to build a state-of-the-art interpretive centre at Sedella in the south and expand the interpretive centre near Fornes in the north, and their 2011 guide to the area (in Spanish) is now widely distributed. Today, walkers with their boots, rucksacks and walking sticks are a common sight in the town of Nerja and the neighbouring villages of Cómpeta, Frigiliana and Canillas de Albaida.

Here there are over fifty mountains over 3000ft (914m) (equivalent to the Scottish Munros), in an area about the size of The Isle of Skye. The highest of these mountains is over 2000m, and a significant number are taller than Ben Nevis. Many of the mountains have maintained and waymarked paths.

To climb the mountains of Scotland and Ireland hillwalkers need to consider that the summit will be in cloud 70 to 80 per cent of the time; by contrast, in Andalucía the figure is more like ten per cent. Spain is also one of the most affordable countries in Europe to visit and there is a universal welcome for the visitor.

The aim of this guide is to provide accurate information and route directions for independent walkers, with lots of background information to make their explorations of this stunning area even more rewarding.

Geographical context

Nerja is a small coastal town 60km east of Malaga, presided over to the north by the Almijaras. The Almijaras are orientated on an east-west axis and they join the Sierra Tejeda to the west and the smaller Sierra Alhama further to the northwest. There are three other minor sierras on the periphery of the region. The foothills of the Sierra Nevada, the Alpujarras, are some 80km to the northeast.

The wider region in which the routes described in this book sit is referred to in Spanish as the Axarquía, which comes from Moorish and means the ‘lands to the east’. The principle towns of the Axarquía are Vélez-Málaga and Nerja but Nerja is the one chosen as the focus of this guide because it is closest to the centre of the mountains and many of the walks included begin there. The official name for the area, promoted by the Andalucían Tourist Board, is Sierras Tejeda, Almijara Y Alhama, which is also the name of the national park. However, most people, Spanish included, may find this title rather challenging.

The gorge of Alhama (Walk 21)

On the path to Lucero (Walk 8)

The town of Nerja

Nerja has a population of 22,000, which grows in the summer to several times this number with the influx of tourists. Many of the properties in the town are unoccupied outside the tourist season. The town is well-known throughout Spain because Verano Azul, a popular soap opera on Spanish television some years ago, was based here. Today 20 per cent of the permanent residents of Nerja are foreigners who have relocated mainly from northern Europe, typically England, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland and Belgium.

The town is a maze of narrow streets that all seem to lead towards the Balcón de Europa, a public square on a promontory above the Mediterranean.

There is no beach of any size in the centre of town, but on the outskirts of the town, to the east and west, there are fine beaches. Nerja boasts many quality medium-priced hotels, hostels and apartments to rent, and there are numerous excellent restaurants, bars and nightclubs. Most of the hotels cater for group bookings and there are discounts in the off-peak seasons.

One of the principle tourist attractions is the Cave of Nerja. Situated immediately northeast of the town, this limestone cave has five kilometres of chambers, many of magnificent proportions, which were inhabited as far back as 25,000 years ago.

The white mountain villages

Frigiliana, Cómpeta, Canillas de Albaida, Canillas de Aceituno and Salares are just some of the quaint, white-painted villages a short distance from Nerja. Several others are visited on the walks. These villages have a history that spans the occupations by the Romans and the Moors and they still pursue old customs and a pace of life that reflects the traditions of rural Spain.

Geology and topography

The mountains of Nerja are largely limestone, but they span 500 million years of geological time. The youngest rocks are the conglomerates that can be seen below the Balcón de Europa, which are only 10,000 years old. The walk to Haza de la Encina, south of Jayena (Walk 23), crosses Pliocene conglomerates that are five million years old. The cliffs of Alhama de Granada (Walk 21) are from the Miocene and so are about 15 million years old. Then we jump back in time to the Jurassic rocks, 180 million years old, for the climb at Ventas de Zafarraya (Walk 19). But the oldest rocks are those that form the main body of the mountains of Nerja and these are 280 to 500 million years in age, spanning geological periods from the Permian back through the Carboniferous and into the Cambrian.

Typical street in Frigiliana

The older rocks were lifted and the mountains formed 30 million years ago during the tectonic collision of a Mediterranean breakaway plate with the land masses of Africa and Europe. This collision caused the formation of the Betic Cordillera of which Sierra Nevada, the Alpujarras and the mountains of Nerja are a part.

The Almijaras mountains above the town of Nerja (L: Western; R: Eastern)

Earthquakes

The mountains of Nerja are in the most active seismic area on the Iberian Peninsula and experience major earthquakes roughly every hundred years. The most notable in relatively recent times was on Christmas Day in 1884 when a tremor measured at 6.5 on the Richter Scale hit, with its epicentre northeast of Canillas de Aceituno. It affected every village and town in the Axarquía, killing 745 people. Further tremors occurred in January and minor aftershocks were felt throughout the following year. The devastation was compounded by heavy snows in the mountains. The King of Spain visited the region, was taken ill and died soon afterwards. The most recent tremors were recorded in 1956 and 2003.

Nerja’s Balcón de Europa

Karst limestone

The limestone varies from white soft chalk to hard, blue calcitic rocks. In the area of Fuente del Esparto there are lenses of black limestone shales, while near Lucero the heat from the mountain building has turned the limestone into marble. There are no volcanic rocks in this region.

There are areas where the limestone is friable, reminiscent of the Dolomites, and other areas where they are Karstic, with holes cut into the rock by acidic solution. The entire area is dotted with caves of all shapes and sizes.

The mountains consist of a main chain stretching from La Maroma (2069m) in the west through Cerro Santiago (1646m), Malascamas (1792m), Cerro la Chapa (1820m), Lucero (1775m), La Cadena (1645m) to Navachica (1832m) and Lopera (1485m) in the east. South of the main chain is a series of foothills of which El Fuerte (1007m), Tres Cruces (1204m) and Cerro Atalaya (1255m) are examples. At Navachica the mountain range opens into a three-pronged fork with Cerro Cisne (1483m) on the eastern limb, Tajo Almendrón (1515m) in the middle and El Cielo (1508m) on the western limb.

A little history

Spanish history is extremely complex and very difficult to summarise so only a brief overview can be given here.

The earliest evidence of human beings in Europe was found in Spain. In a cave near Zaffaraya in 1933, bones were discovered that are believed to have belonged to Neanderthal Man, dating to 30,000 years ago. There is also evidence of prehistoric life in the Cave of Nerja. Near Fornes in the extreme north of the region there is a passage grave that has been dated to the Neolithic period. The Iberian Peninsula is known to have been visited by the Phoenicians and the Greeks before the arrival of the Romans, some 200 years BC. Hispania, as it was then known, was ruled from Rome for 600 years.

Roman aqueduct at Torrecuevas (Valley of Rio Verde)

From around 400AD to 700AD the peninsula was conquered by the Visigoths, who were subsequently replaced by the Moors. These Muslims ruled Spain until the early 13th century, when the Catholic Conquest began. In the Axarquía there was considerable Moorish influence. It can be seen today in the Alhambra in Granada. Mudegar architecture is widespread and all towns and villages with names beginning with ‘al’ betray their Moorish origins. The climate in Andalucía was ideal for the silk industry set up by the Moors. Even to this day we can see the Arabic features in the people of Andalucía more than in the rest of Spain.

During the Muslim period there were three main religious groups – the Muslims, the Christians and the Jews. Strangely enough the Jews allied themselves to the Muslims and lived in close proximity to them as their protectors from the Christians. After the Catholic conquest all people were required to convert to Christianity or face death or expulsion. The majority of the Muslims did so convert and were then known as Moriscos, but the Jews substantially packed their bags and left the country.

From late in the 19th century to the beginning of the First World War Spain was torn between disputes over the monarchy, a republic and dictatorship. During the Spanish Civil War and for many years after it in Andalucía, and particularly in the Axarquía district, there were many enclaves of republicans who resisted the dictator General Franco, and there were many bloody encounters. The mountains visited on these walks were ideal refuges for the Maqui, the republican sympathisers, to hide in.

Cabras montés

A good introduction to the history and culture of the region is La Axarquía – Land to the East of Málaga by Hilary Gavilan (see Appendix D).

Wildlife

The wildlife and plants of the Spanish hillsides are truly remarkable and very different from those of northern Europe. There are very few dangerous creatures about, and where there are they will be as nervous of you as you are of them.

The cabras montés are only found in the Iberian Peninsula and the vast concentration of them is in the Axarquía. You will glimpse them all the time but these wild goats with deerskin hides are very shy and will move away from intruders. They are extremely agile and will often be seen travelling up and down slopes at great speed. In the area around La Resinera, you may also encounter red deer.

Processionary caterpillars

Seeing wild cats, foxes and hares will be a rarity. Similarly, snakes are shy and infrequently encountered. There are many birds of prey to be spotted hovering in the skies, including kestrels, falcons, vultures and even eagles.

The most dangerous insects in Spain are processionary caterpillars. They make their woven white nests in the branches of pine trees and emerge in lines that may be several metres in length. However docile they may seem, they can eject a nasty poison from their hairy backs.

Plants and flowers

Flor de Jara

The mountain flowers come to life in the springtime, when many familiar species and others that are particular to the Mediterranean will be better seen. On the slopes of El Fuerte the exotic Flor de Jara thrives. This bush is related to Cistus – Rock Rose, and it likes lime-rich soil. Where the Spanish name for a plant or flower mentioned in the route descriptions is available it is given, and some of these are very interesting. For example, the poppy in Spain is an amapola (wet land); broom is lluvia de oro (rain of gold).

The most common tree to be seen on these walks is the pine tree. However, in the past yew trees predominated here. Sierra Tejeda takes its name from the Spanish word for yew, tejo. The yews were cut down because they were considered to be poisonous to livestock and pines were planted in their place to expand the resin industry. The demise of the yews is highlighted in the interpretive centres and a programme has commenced to replace some of them. The pines are well adapted to withstand drought. The red berried prickly juniper features on the Almendrón walk (Walk 6). Holm Oaks – the evergreen Holly Oak – have adapted here to survive the dry summers.

If you want to read more about Spanish wildflowers, two field guides are recommended in Appendix D.

Getting to Nerja

Nerja is 40 minutes by car from the city of Malaga. The airport at Malaga is one of the busiest in Spain with flights into it from almost every country in Europe. Easyjet (www.easyjet.com), Ryanair (www.ryanair.com), Monarch (www.monarch.co.uk) and British Airways (www.britishairways.co.uk) all operate regular flights to Malaga from various cities in the UK. From outside the airport terminal there is a regular shuttle bus into the main bus station in Malaga, from where there are regular buses to Nerja. The fares on these buses are remarkably cheap.

Car rental companies (such as Malagacar, www.malagacar.com) vie for custom at the airport, but it will be more economical to compare prices online and make a booking before arrival. Some companies rent their cars with a full tank of fuel and ask for it to be returned empty; an obvious advantage for them since returning it empty is rather impractical. There are a number of car rental companies in Nerja (such as Autos Tívoli, www.autostivoli.com), but their rates are generally not as competitive as those at the airport. Many of the approaches to the walks in this book involve driving on dirt roads so you may prefer to rent a high wheelbase car or even a small offroader.

A taxi from the airport and back is likely to be costlier than hiring a car, but there are companies (all in Nerja) that ferry people on a taxi-sharing basis.

The airport at Almeria to the east is more than an hour from Nerja and is not served as well with buses and car rentals.

Malaga can also be accessed by train or bus from the cities of Madrid, Seville and Cadiz. Spanish train timetables can be checked and tickets bought online at www.renfe.com and bus times and tickets are available at www.alsa.es.

Accommodation

The kiosk in Frigiliana

All the routes in this guide could be done in a single day trip from Nerja, so Nerja is a good place to base yourself for your trip. There are hotels in Nerja that specialise in group bookings for walkers. Since walkers generally come in the spring or autumn, out-of-season rates apply. These hotels operate on a bed, breakfast, packed lunch and evening meal basis, or on variations of these.

The hotels specialising in catering for walking groups tend to be medium to small hotels, but there are a few luxury establishments in the town as well. Equally there are hostels that are economic and operate on a bed and breakfast arrangement. A useful source of information about accommodation in Nerja is www.nerjatoday.com.

For those who want to fend for themselves, Nerja has many empty apartments available to rent in the off season. Almost all of the real estate agencies in the town provide this service. The option of renting and eating out is very practical, for there are numerous cafés and restaurants that open early and serve anything from coffee and rolls to a full English breakfast. For evening meals there is a wide choice – English roasts, Italian pastas, Indian curries, Mexican spices and many fine establishments serving the best of Spanish cuisine.

The choice of accommodation location lies between proximity to the town centre, the beaches and the mountains. Nerja town centre is a maze of narrow one-way streets, decidedly not car-friendly. So, cars may have to be parked remotely from accommodation.

The bus from Malaga arrives at the top, or eastern end, of the town. It is a 10-minute, downhill walk to most places within the town, but there is a taxi rank at the bus station.

When to go

In the spring, the paths on the north side of La Maroma can be covered in snow

Officially it has never rained in living memory in Nerja during June, July and August. However, as well as being dry during these months, the weather is hot and the town is packed with tourists. In this high season everything is that little bit more expensive. While the coast is basking in heat the mountains tend to be shrouded in cloud. The Nerjans say that the town has its own microclimate such that it never gets unbearably hot and does not suffer from the high humidity of other coastal towns.

For the hillwalker the best time to go is in late April and early May. There may be a little snow on Maroma, but otherwise the temperature is ideal for walking: not too hot and with little threat of rain. The flowers will be in full bloom and the landscape will be green. In early April the flowers will be out, but the rainy season has not yet concluded. The two biggest festivals in the town take place over Easter and on 15 May. Religious processions are big throughout Andalucía, when a significant proportion of the townsfolk take part. Spanish tourists pour into the town to witness the dedication that the community has to its processions. The spectacle is a moving one.

In late summer and early autumn the weather will again be very suitable for walking, but after the hot summer the land will be brown and scorched. From November through to April walking in Andalucía is still very acceptable, although you are now more prone to rain and possibly snow on Maroma. There will be more water in the rivers, many of which must be crossed on the walks, so that getting feet wet may become inevitable. Snow on the Almijaras is rare, with Navachica the most vulnerable. There is never any snow on Lucero because the high winds remove it, but there can be snow on the northern approach to its summit.

The dirt track road into Pinarillo and Fuente del Esparto is (sometimes) closed from 1 June to 1 October, because of the threat of forest fires. This adds considerably to the length of Walks 5 and 6 and this is indicated in the route descriptions.

Walking in Andalucía

The path into the Rio Verde valley (Walk 17)

The Andalucían Parque Nacional has set up and now maintains designated walking trails, and many of the walks in this book follow such trails. The paths are often old mining routes or former mule tracks through the mountains. All of these maintained paths are waymarked. They have a sign at the start of the walk (in Spanish) with notes on what you are about to encounter, a little history, the distance and time it will take and the relative difficulty. It is important to note that the time given on these signs is always for a one-way trip and does not include your return to the start.

The waymarks indicate the direction; where other paths link there are waymarks with crosses to show that they are not to be followed. All waymarked paths have relatively moderate gradients. For the experienced walker this can be a little frustrating because the route is extended to maintain the gentle gradient and becomes laboriously long. In this book shortcuts have been adopted for the most excessive cases.

Many of the walks are not on waymarked trails, which tend to be more challenging. Over time paths can be subject to change: from earthworks, landslides, river flooding and vegetation encroachment and so on, so that you need to keep your wits about you.

The most important thing is to find the start of the path and be sure that it is the correct path. Once you are on a path all you need to do is follow it. Wandering off the path is generally not an option because of the surrounding vegetation.

Almost all the land in this area is in public ownership and is part of the national park. The exceptions are areas immediately north of Frigiliana, part of the Rio Verde Valley, the eastern walk of Ventas de Zafarraya, and land north of Maroma. There are signs indicating when land is private and none of the routes in this book require you to trespass on private land where it is so indicated (although Walk 20 does follow a public right of way that passes through private land).

Spanish dialect in Andalucía

The Andalucíans have many peculiarities in their speech that differ from the Castellaño that is spoken in Madrid. The language sounds much smoother here, not as harsh as that of their northern neighbours and more akin to the Spanish of South America.

For example, the word ‘Andalucía’ is pronounced as it would be in English, whereas in Madrid it would be ‘Andaluthia’. The English pronunciation of the name ‘Nerja’ is ‘Nerka’, but to be more correct it is ‘Nerha’, with the ‘h’ pronounced gutterally.

The river that flows through the town is the Rio Chillar, which is pronounced Chiyar, because two ‘l’s are pronounced as a ‘y’ in Spanish.

In Andalucía there is a tendency to drop all ‘s’s in the middle and endings of words. So to buy two beers (dos cervecas) the request would be ‘dos thervethas’ in Madrid. In Nerja, ‘doe cervaytha’ will be heard, or for three it will be ‘tray’. To ask how a person is one would say ‘como estas’ in Madrid, but in Nerja it would be ‘como ayta’, both of the ‘s’s having been dropped.

The Spanish pronounce all of their vowels individually (not as dipthongs, as native English-speakers do). So the unit of currency is an ‘ayuro’ and the mountain of El Fuerte is pronounced ‘El Fuuertay’.

Recurring place names

There is a degree of repetition in the names of geographical features. There is a Puerto Blanquillo and a Puerta Blanquilla; there are at least two Salto de Caballos, two El Fuerte mountains and a couple of Cerro Verdes; one set of peaks is known as Los Dos Hermanos (the two brothers), a col on Cisne is known as Collado de los Dos Hermanos, while another peak is called Las Dos Hermanas (the two sisters). To the north of the region there is the town of Arenas del Rey, while nearer the coast there is the village of Arenas. But as long as you know where you are, there should be no cause for confusion!

Red deer

Maps and GPS coordinates

Topografica publish the official National Geographic Institute of Spain (IGN) 1:50,000 and 1:25,000 maps of the area laid out to the 1950 European UTM grid. These maps are relatively inexpensive to buy but are not widely available. The quality of paper is poor and all paths are not shown on them. For some of the walks more than one map will be required. They can be purchased direct at a shop in Malaga, or they can be purchased online (see Appendix E, ‘Maps of the region’). See Appendix C for a glossary of useful words for map reading.

The Axarquía Tour and Trail 1:40,000 published by Discovery Walking Guides is quite a clear map, but the October 2010 version has many little mistakes (for instance, Frigiliana and Canillas de Aceituno are misspelled, and there are a number of features that are out of place). Unfortunately the 2010 version is to an imperial grid.

A GPS is not essential for most of the walks. There is often not a great deal of point in giving waypoint coordinates. The key thing is to find the start of the walk and stick to the path. However, for walkers who prefer to carry a GPS device of some sort, some waypoints have been identified in the route descriptions at particularly critical navigational points. The GPS coordinates set out in the guide relate to the European Grid and are in metric. The coordinates given, for example 215:420760:4087650, are made up of height in metres: easting in metres and northing in metres.

Using this guide

The approach to Collado de Dos Hermanos on Cisne (Walk 24). The mark on the rock shows that there is only 100m of climbing left, but it is the most difficult 100 metres

Some summary information is provided at the start of each route description to help you select the right walk for you and your party. This includes the total distance, the total height gain, a rough estimate of the time a walk might take (allowing for reasonable rests and refreshment breaks), a difficulty rating and directions for getting to the start of the walk from the nearest town or village. Other options for your day in that particular area are also suggested in some cases. There is also a summary table in Appendix A to help you compare the different routes.

Route maps

The routes are marked onto 1:25,000 IGN base maps, except for detailed navigation through villages where street maps, with scales indicated, are provided. The main route line is marked in orange and variants are marked in blue. There are some inaccuracies in the base maps and so in some cases key features have been marked over the top in heavier black type with an arrow to pinpoint the correct location.

GPX files for all the routes described here are available for anyone who has bought this guide to download free from the Cicerone website. Just go to www.cicerone.co.uk/754/GPX. All the official Spanish mapping is also now available to buy, by map tile, province or region, for use within the ViewRanger navigation app on tablets, phones and other devices.

Difficulty

The difficulty rating given for each route is on a scale of one to ten with the higher numbers reserved for long and strenuous walks. A route with a difficulty rating of 1 would be suitable for children and grandparents and where ordinary sports shoes would be appropriate, while one rated 10 should be reserved only for those who are very fit, in good walking boots and with all the essential gear for eventualities in the mountains, and, of course, the stamina for long and strenuous walking. The climb of Cisne poses particular risks that are set out in the notes for that walk.

All of the walks are suitable for regular hillwalkers.

What to take

A view down over Fornes (Walk 22)

During hot months in the mountains it is essential to bring an adequate quantity of water or other fluid. (‘Adequate’ will vary from person to person but 1–2 litres per person is a good rule of thumb when exerting yourself in a hot climate.) Water sources on the walks are generally poor to non-existent.

Wearing shorts will be appropriate on many of the easier walks, but for the more difficult walks through thick and spiky vegetation long trousers or leggings are required. This particularly applies to Walks 1, 5, 6 and 16, and the eastern section of Walk 19.

You could encounter snakes on any of the walks in this book but it is highly unlikely. They will be more scared of you than you are of them and will keep well away if they can. However, it may be wise to wear gaiters in areas of thick vegetation. On the walk on El Cielo, in particular, ankle protection is recommended, because you will not be able to see the ground clearly on the first half of the walk.

False smooth snake

The routes in this book are not technical. The only walk for which roping up is recommended is the ascent of Cisne, at the point of the traverse on the eastern side of the summit.

Likewise, a GPS is not necessary for most of the walks in this book. However, you should take one if you are going to tackle the walks to Almendrón (Walk 6), Navachica (Walk 16), Malascamas (Walk 20) and Cisne (Walk 24).