Читать книгу The Etiquette of Freedom - Jim Harrison - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

WILL HEARST

The chance to make a film is always a long shot. Unlike a poem, it’s a collaborative game. No one person controls all the variables. This is how it happened . . . this time.

In the late ’60s while I was still in school, but more interested in sex, travel, and girls than in scholarship, I became interested in the literature of the Beats. This had something to do with California. I was raised in the cold granite corridors of New England, but we spent summers in the West, a sunset land of freedom, possibility, bigger vistas, and hot weather. I wanted to write, live, like Kerouac.

I read The Dharma Bums, and I liked that book better than On the Road, which is of course Kerouac’s masterpiece. I loved the originality, the story, the depiction of that hip Mill Valley scene, and the marvelous language. But one of the things that stood out in that story was the portrait, in a fictional setting, of the character Japhy Ryder. This person who remains at the center of the action is a vivid character with a particularly different and unique point of view. He has his own interior compass, and that character always fascinated me.

By the ’70s I discovered the poetry of Gary Snyder, Rip Rap and Cold Mountain Poems, and loved it because it had such a feeling of the West. He wasn’t a New England academic; there was something fresh and Western about the voice of that poet.

Sometime later, and I don’t remember exactly when, I finally uncovered, in a biography or some criticism, that the real poet Gary Snyder was the person on whom the character Japhy Ryder had been based.

I think that was the birth of this project. It became a detective story. How did they connect? As time went by and the Beat Generation began to pass from the scene, it occurred to me that Gary was still practicing, and I became interested to see if he would write for the newspaper. By that time I was the editor and publisher of The Examiner, in San Francisco, and we had an Op-Ed page feature, which was a relatively new thing at the time, where we invited people who were not part of the staff of the paper to write essays and editorials and generally nonfiction material.

So we asked Gary if he would be interested, and he sent back this absolutely beautiful essay later republished in his collection, The Practice of the Wild. Clearly this man, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, could write simply beautiful prose: thoughtful, scientifically grounded, but with a haiku voice.

More time went by, and I met Gary a few times and got to know him, and I continued to believe that he had a wonderful gift with words. He had a clear, unusual mind, and there was something utterly unique about him and his work. And the relationship between the poetry and the poet began to come into focus in my mind. He had a view of the natural world that transcended politics as usual. He was like Japhy Ryder, but he was not Japhy Ryder. Still, I don’t think I knew Gary very well.

At another point, working to help found Outside magazine, I came to know, distantly, Jim Harrison, who was also a poet but perhaps better known as a novelist. Jim had written a very funny but highly irreverent profile of his fishing trips in Key West. It was so raw I wondered if it could ever be published. My first impression of Jim was that he could not abide any kind of flattery, and he could detect a false note with the precision of a delicate radiometer. Even on the telephone one could hear in his raspy voice and fine diction the influence of poetry.

It was not until after the year 2000, maybe twenty-five years later, that I really got to know Jim and spend time with him. We became friends, and so one day I posed the idea to him, in the form of a question: “Hey, do you think it would make sense to try to make a documentary picture, a kind of profile, of Gary Snyder?” And Jim, to his credit, instantly said, “Yeah, I think that’s a great idea, you ought to do it. And in fact, I will help you, I know Gary, and I will talk to him about it, and I will do the interview.”

So I thought, Wow, okay, so a smart writer like Harrison thinks that the idea of doing a documentary on Gary makes sense. So that gave me some confidence to do more work on the project. But I was slow to pull it together, more time passed, and I remember very distinctly a weekend barbecue with Jim Harrison, and he pulled me aside and said, “Hey, what happened to that Gary Snyder project?” And I said, “Well, I’d still like to do it.” And he said, “Why don’t you stop liking to do it, and actually do it.”

That was the final kick, or spur, to put together a crew, raise money, and talk to Gary more seriously; Jim was an enormous help there.

A documentary is a piece of journalism; you don’t go into it with your story already written. You go into it to find out what the story might be. I knew Gary would make a good interview. I also knew he could be quite terse in the way that he spoke. I had no doubt that once we got him going we would find more than enough material; one thing would lead to another. My background convinced me, if you have open access to a subject, you ought to be able to find the story.

But Gary said he didn’t want to be interviewed at his house in the foothills; it’s been done before. He said, “I’m tired of it, and I don’t want to be a Beat poet cliché.” Things were stalling, when Jim had an idea. My cousin had done a lot of work to create an agricultural easement at the Piedras Blancas ranch down on the California coast. The net effect was that this land, this very beautiful section of grass and range country at San Simeon, would stay undeveloped in perpetuity.

It also meant that it was going to remain a desolate cattle ranch and was not generally open to the public. So Gary, prompted by Jim, said, “I tell you what: I’ll give you the time, and I’ll sit and be interviewed, and I’ll spend several days with you, but let’s shoot it down at the ranch, because I’d like to walk it, and I’ve never seen it, and I like the Central Coast.”

We still had to assemble a crew, to find the right people who had a feeling for the subject. I knew the director should be John J. Healey, who had already made a documentary in Europe about the poet Federico García Lorca.

Casting is time well spent on any project. You have a feeling in advance, because you love the script, or because you believe in the subject, of how the movie will go . . . but something else happens when you start to shoot. The best people bring their A-game. They add to the show. Fresh things begin to happen. The movie starts to unfold itself.

As a producer, you learn the most important thing you then can do is feed everybody, see that they are comfortable, and worry about the cars. As Napoleon Bonaparte observed: “An army marches on its stomach.” Think about food, fuel, and transportation.

Finally, when the filming ends, the editor looks at everything you shot and tells you here is the movie you made. It changes again. Music and sound, which seemed so peripheral, begin to shape and cue the action. Your child has begun to walk on her own legs.

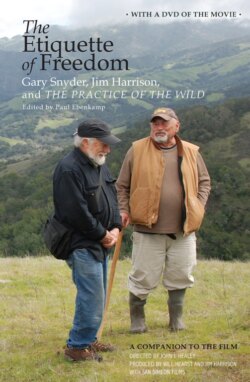

So we had a great locale and a commitment to participate. When Jim and Gary got together and started talking, all we really had to do was make good sound and frame the shots. The story of Gary’s life and how he came to think the way he does emerged from their conversations.

Like any good profile, like something you might read in The New Yorker, you discover so much more when you hear the actual words of the subject, and see the animation in their eyes, than you would ever have learned by merely researching that same subject.