Читать книгу The Etiquette of Freedom - Jim Harrison - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

JOHN J. HEALEY

I worked in production in the feature film business as an assistant director for fifteen years before I decided to make documentaries. Taking advantage of the fact that I had a long history with Spain, good relations with the Lorca family, and an important date was approaching, I made my first film in 1998 about the life and work of Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca. It was aired in Europe in June of that year, marking the hundredth anniversary of his birth. One of the people who contributed to the financing of that film was Will Hearst.

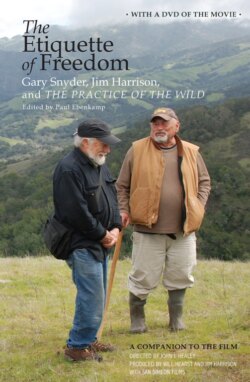

Will became friends with Gary Snyder and Jim Harrison when he was still in the magazine and newspaper business, and the idea to do a film on Gary came originally from Jim, I believe. The concept ebbed and flowed over a number of years, and when it reached critical mass Will called and asked me if I’d like to direct it.

I knew Jim Harrison’s work because I have been a serious reader of fiction since my teens and Jim’s oeuvre held a solid place on my list of favorite contemporary literature. But I knew very little about Gary Snyder. There is some irony in the fact that both of my documentary films to date have had poets as their subject. I myself have never been a great reader of verse.

Will flew Jim Harrison and me to San Francisco in November 2008 so that we could meet and scout locations. Jim had already been working on a list of questions for Gary, and Will and I added some of our own. Jim is an easy man to love. He is very wise and very funny, at ease with his id, and a gentleman. After a long dinner at the Zuni Café, his worries about me, I think, subsided. The opportunity to shoot the film on the Hearst Ranch resonated with me on different levels. I have been a guest there during various phases of my life since I was fourteen, and it is one of my favorite places on this Earth. On that November trip Cynthia Lund and I flew down on a little plane, landing on the ranch’s airstrip where I had first learned to drive a stick shift. We were met by Will in his Jeep and by master ranch hand Bill Flemion in his massive pickup. We drove all over the place that day, including to some extraordinary locations that were quite far away and required significant vehicular stamina to reach. In my head I already knew that, barring some compelling reason, we would probably not be able to film at these more distant locations once we had our “cast” and crew assembled. Weather would also be a factor. Driving on the ranch in November was still relatively easy, although Will’s Jeep did work itself deep into a mud hole at one point. But generally it rains along the central California coast during December, January, and February, and the shoot was scheduled for the last week of February, so it behooved us to find places we liked that would also allow us to stay relatively close to structures where we could shoot indoors if forced to.

It was during this trip to California that we interviewed potential crew members. We went with Claudia Katayanagi for sound because she has the right level of technical obsession and because she had worked on something with Gary Snyder once before. We chose Robin Lee to edit the film because, in addition to his calm demeanor and enthusiasm for the latest digital editing techniques, to our astonishment he was extremely familiar with Gary’s work. We chose Alison Kelly to shoot the film because after interviewing some very competent Bay Area cinematographers with deep documentary experience, she was a breath of fresh air, a woman more at home with independent feature films, who has a great technical competence, a wonderful sense of humor, and a serious commitment to quality. Our mutual respect for Terrence Malick also helped to seal the deal. Before flying back to Spain I went to City Lights with Jim and bought everything Gary had ever published, and before the month had ended I had read it all.

Cut to February 2009: I returned to San Francisco a few weeks before the shoot to review and choose the archival material we would be using. On the way there I stopped in New York to visit the Allen Ginsberg Foundation, located in Ginsberg’s last residence in the East Village, where a wonderful collection of photographs is kept.

The weather was not auspicious. It was raining often during the second half of February, and during my drive from San Francisco down to the ranch on the twenty-third it rained on and off. By the time I arrived at San Simeon all the crew were there, most of them up from Los Angeles in two white vans packed to the gills with equipment. After loading everything into a staging room at the bunkhouse, we had a catered dinner together and watched the Academy Awards ceremony on a big flat-screen TV. This was Will’s idea, and it was a wonderful way for everyone to break the ice and to start feeling comfortable with each other. We spent the following morning doing a tech scout of the locations, shooting tests, and preparing the room at the bunkhouse where the first interview would take place. I thought it best to do our first day’s work in a controlled atmosphere, making things as easy as possible, giving the crew a chance to get used to each other, before going out into the wild with vehicles and steady-cam gear and all of the additional paraphernalia one needs when shooting on the fly and off the grid. I should add that an additional advantage to shooting everything at the ranch was the terrific logistical support we had, the vehicles to get us everywhere, the amazing cooking team flown in for the occasion who spoiled us rotten, and the cocktail hour celebrated on location each afternoon wherever it was we happened to end our day. All of this went seamlessly thanks to the sterling organizational skills of our associate producer, Cynthia Lund.

And so it went. After spending all day on the extensive first interview, we spent the rest of the shoot filming at one location during the morning and at another in the afternoon. The weather gods were with us. With the exception of one somewhat cloudy and blustery day when we filmed the ridge walk, it was all sunshine and glistening green vistas. The crew was wonderful, displaying a professional dedication to getting things right regardless of the hour or distance to the location. We had the great luxury of working with three cameras, and that required significant preparation each time we changed setups. But it proved to be a good system. The last thing I wanted was to have to ask either Gary or Jim to repeat what they had just said for need of a different camera angle.

Of course, by the time we got to the last day, the whole company was up to speed, in synch, and working like a Swiss watch. This is always a cause for some frustration on short shoots. The last thing we got with Gary and Jim present was the dinner scene that precluded an official wrap-party dinner. On the following day many crew members started heading home. But the department heads and our extra camera operators remained, and it was on this final day that sound went out to record nature and the camera crew went hunting for beauty shots on the ranch. Some of the best material we got and that made it into the final cut was captured during those last hours.

“Directing” a documentary is not the same as directing a fiction-based narrative film with actors pretending to be other people. In the latter case, the director’s main job is to make sure the performances ring true. In the case of a documentary film, you want your main subjects to be as comfortable and true to themselves as possible—you want to do all you can to urge them along without getting in their way. Later, in the editing studio, you get to see all that you have, and it is there the film begins to take shape.

The two men we see in this film are national treasures, as singular and talented and American as they come. It was a privilege to get to know them, to be trusted by them, and to be able to do all I could to render a final product worthy of them.