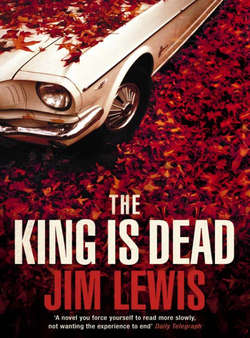

Читать книгу The King is Dead - Jim Lewis - Страница 23

17

ОглавлениеHe had been eighteen when he joined the Marines, a year behind his brother Donald’s enlistment in the infantry. He had shipped out from San Diego to Honolulu, and he’d gone, as much as anything, because he wanted to get out of the South. There was no reason why he chose the Corps, except that the story of the sea was so distant from the story of his family, and he had an eighteen-year-old’s desire to exploit the distance and impress his dead forebears. A few weeks in training and there he was, waiting in Hawaii to be cast into battle.

There were ten thousand troops on base, all sorts of men, with all sorts of reasons, and many with no reason at all. Walter had never seen such an array, such opposition and jumble: from fair to tan, from soft to savage, from swift to slow. They came and went through the barracks and depots; they rambled along the dry roads, falling in and out of patterns like glass chips in a kaleidoscope, according to ties of time and origin, inclination and impulse. They spent days maintaining their gear, cleaning this and oiling that, and nights lying on immaculate, evenly spaced bunks in their barracks, waiting and boasting, with the smell of the sea all around them, and the long rhythm of the surf as it repeatedly gathered itself and broke against the shore.

Within a few days a set of alliances had formed, gangs among them: Irish from Chicago, the Northwest Loggers, college boys, they found one another and fell in as easily as if they were following orders. Walter was a member of the Austral Gentry, heirs to the manners and the land from the Carolinas to the Mississippi, from the Mason-Dixon Line to the Gulf Coast. There was MacIntire, Hamilton III, Lukas from the hills of Georgia—good boys all.

There was one more fellow, a small, wiry man from the outskirts of New Orleans named Chenier. He was a little bit older than the other men, and he looked older than that, because his skin was rough and dark from standing in the sun, and his nose had been flattened in an adolescent fistfight. He was a Cajun; most of the men on board could hardly understand him through the meal of his accent, and this, too, separated him a little bit from the others. He smiled crookedly, smiled slightly madly, and spoke in a crazy dirty French mumble. During his days in stateside camp a sergeant from Louisiana had dubbed him Coonass, and he carried the name with him, all through his deployments.

Some of the men took in his dark skin, his mumble, and his nickname, and decided he was a Negro, if not in whole then in substantial enough part. Warren from New Hampshire may have been the first to suggest it, one evening while he stood at the base of his bed, peeling wide papery flakes of sunburnt skin from his shoulder. I don’t know about all this work outside, he said. A civilized man doesn’t stand in the sun. The invention of culture was simultaneous with the invention of indoors: palaces, cathedrals, libraries, legislatures.—He made a gesture like a man sprinkling a pinch of salt, and the skin fell from his fingers to the floor.—Where does an evolved man eat? In a dining hall. Where does a wise man lay his lovely wife? In the darkened privacy of his chambers. Oh, the sun is a fearsome thing: the Greeks called him Apollo, the son of Zeus himself. The Egyptians called him … What did the Egyptians call the sun god, Brammer?

Fuck if I know, said Brammer.

Warren peeled at his skin some more. Everything the sun sees, it destroys, starting with a man’s own flesh. Myself, my father, his father, and his father before him, all treated the sun with a healthy respect, and the Warrens have always been the paler for it. Now the Corps asks me to stand in the sun all day, just so my rifle won’t get lonely. Hence, I burn. It is the mark, I say, of a civilized man.—He gazed imperiously around the room. Now, Chenier, for example, doesn’t burn. In fact, Chenier is getting mighty dark. Where you been, Chenier? On your own little Africa campaign?—Laughter all around, and the conversation turned.

Then a unit had been finishing maintenance on a cannon when one of the men spotted a slick of oil beneath it. It was evening; the sun was red on the horizon. Sergeant isn’t going to like that, said a Voice of Fearful Mourning. Somebody’s going to have to stay behind and get it cleaned up.

Let the nigger do it, said a Voice of Young-Old Dudgeon.

He meant Chenier, and Chenier, who was on the other side of a crate of shells and didn’t hear him, accepted the assignment without knowing why it had been left to him, spent an hour on the job, and then ran to the mess, where he sat at a table with two of his battalion mates, who rose pointedly from his presence and took themselves across the room.

Well, an argument went, over boilermakers and under a bitter yellow moon. Coonass was a black man, snuck in by the Department of the Navy under the guise of being white, because Roosevelt wanted to prove his principles. No time better than a war, when great masses of men shifted around the world, and all societies were transformed. Somebody had to be planning it: somebody had to be keeping track, from start to finish. One Negro man in the Marine Corps.

Chenier paid no mind. He’d heard worse, he’d done worse. He was thirty years old, his teeth were still strong enough to bite the head off a penny-a-pound nail, and his hair was still thick; he didn’t care what young men thought. It was just as well they left him more and more alone, to fall back on his tangled inner tongue. He wrote to his wife in Slidell, telling her it wouldn’t be long until the day he climbed back into bed with her, and banged her until the walls shook.

Then there came a Wednesday night when leave appeared, like an alignment of the planets, for Lukas, Hamilton III, and Walter Selby. It was a fine night, a fine fortune, the palms were rustling, the wind was up, and the three men strolled the walks with careless ease. At the motor pool stood Chenier alone, dressed in his immaculate uniform and a sour-smelling aftershave. He nodded hello to the boys and turned back to his obscure thoughts. Hamilton III took the others aside in a spirit of gallantry born out of the tedium of waiting, as surely as his ancestors’ had been born out of the tedium of the fields. Listen here, he said. I don’t care what those boys say. Coonass is a man of honor. Coonass is an upstanding representative of the values and tradition of the United States Marine Corps. And Coonass is going to accompany us on a goddamn drunk.

Walter Selby went to Chenier and made the invitation, and Chenier accepted with a shrug, neither ungrateful nor quite glad.

Where were you going, anyway? Lukas asked him as they started into town.

Don’t know, said Chenier. Just going into town to get a drink, maybe look at the femmes go by.

The femmes, said Hamilton III. That’s good. What kind of femmes do you like?

Chenier said nothing, but he smiled broadly in response, his wide lips curling back immodestly.

We’ll see what we can do, said Hamilton III.

They began at sundown in a bar on a hillside and progressed down toward the water, as if in a dream of drowning. In one dark beery place they became bogged down—Lukas wanted one of the waitresses and insisted on staying until he could proposition her—but in time they moved on. Their faces grew red and their eyes grew wet, ten o’clock came at Lonesome Bob’s, the Best of Honolulu, where they ordered rum and coconut milk and stared at the center of the scarred round wooden table.

I left a girl in Abilene

I left a girl in Abilene

Prettiest girl I’ve ever seen

Waits for me in Abilene.

I want to go dancing, said Lukas. Let’s go find us a dance somewhere. You a dancer, Coonass?

Chenier nodded, his face serious and proud. King of St. Tammany Parish, he said. Ain’t nobody better.

There’s a big band down at the Regis Hotel, said Walter. Let’s go, then. Let them swing.

Let them swing, said Lukas, and they rose a little unsteadily and started back into the night.

The hotel ballroom was dark but the bandstand was bright, the music was hot and loud, and Chenier could dance just as he said, jitterbugging furiously, with his hat clenched in one hand and a local girl grasped by the other, his lined face shining and a smile fixed upon his features. Walter watched him with a combination of curiosity and admiration, as if the other man were an exhibit of some sort, a demonstration of human physical skill taken beyond the practical and into festive excess; and he danced one song himself, with a tall, heavily made-up woman with straight black hair and ocher skin, and then retired to the bar, where Lukas and Hamilton III were waiting.

Look at that man go, said Lukas. Chenier had loosened a button on his dress shirt and his legs and arms were flying this way and that.—He looks like a goddamned rooster trying to fly. Can’t compete with that: let’s get drunk. Bartender! You got any bourbon in behind that fancy bar of yours?

Then it was midnight and the band members were taking their bows, there was applause all around, and the three of them were as blind as worms, as bent as worms and with as little left to lose. Last hours on earth. Outside, the palm trees were being whipped around by a dark Pacific wind; inside, Hamilton III was lecturing to no one. My mother … he started, and then he stopped again, as if mentioning her was all he had intended. Coonass had come off the dance floor soaked in sweat, his hair as wet as if he’d just stepped out of the ocean. A big round-faced sandy-haired boy was waiting for him at the bar, watching him as he came across the polished floor, finally laying hands on the bar top and huffing for air as he gazed down to the far end, where the bartender was wiping up a spill.

Tell me something, nigger, said the sandy-haired boy. He wiped his small bent nose with the back of his hand and sucked back the water from his lips.

Chenier shook his head. Not so, he said, though he was so breathless it came out in a single slurry syllable. It made no difference at all. The sandy-haired boy put his hand on Chenier’s shoulder and squeezed a little.

Tell me, how did you get in here? You’re a sneaky little son of a bitch, aren’t you? Sneak your way into a white man’s Marines, where you don’t belong. Sneak into this hotel.

Down the bar Walter noted a certain dissonance in one corner of his consciousness, but it was late and he didn’t want to look, so he turned slightly, facing himself a little farther toward the dance floor, where a pair of Red Cross girls in chiffon dresses were holding hands and giggling about something.

You’re crazy, Chenier said to the sandy-haired boy. I don’t need no trouble.

Yes, said the boy. Yes, yes, yes. Yes, you do need trouble. Why don’t you come outside, and I’ll show you what you need? Come outside, and I’ll shove your black head up your black ass.

Chenier said nothing and didn’t move. The sandy-haired boy smiled and nodded to a pair of friends who were standing in the corner; the two friends smiled back, and then turned and left the bar. Idly, Walter watched them go. He studied his hands; he gently rocked his glass. Chenier caught the bartender’s attention. Shot and a beer, he said, and he cocked his head up to look at the chandeliers in the mirror behind the bar.

You can’t serve him, said the sandy-haired boy. The bartender made a puzzled face. Don’t you know who this man is? the boy continued. The bartender shrugged. This man, said the boy, is of the African race. Now … now … now, I don’t know how he got here, I don’t know who he lied to, or what. I don’t even know why he’s trying to pass. They’ve got plenty of places of their own. But I’ll tell you this, he insisted, leaning over the bar top. You keep serving him, and no white man is ever going to want to come in here again.

That’s enough, said Chenier. In the dim light he suddenly looked very much older, more formidable as a man, but also more frail.

It’s not even close to enough, said the sandy-haired boy, leaning in, and Chenier sighed. Come on outside, and we can settle this real quick.

Can I get a drink, my friend? said Chenier to the bartender.

Why don’t you boys take care of whatever you’ve got between you, said the bartender. Go take care of it, and then you can come back in and have a drink, O.K.?

The sandy-haired boy waited while Chenier stopped by Walter’s end of the bar to pick up his hat. By then Harrison III had begun the saga of his mother, her many marriages, her money, her mansion. The Cajun paused and leaned in to listen.

What’s going on? said Walter.

I don’t know…. said Chenier, slowly. This boy here seems to have a problem with me.

The sandy-haired boy smiled and spoke loudly from down the bar. I’m going to teach your nigger friend a lesson, he said, but Walter made no effort to argue with him; he was too drunk to quite register the insult, there in such crimson luxury with women and music; it caused him little more than a thought to the wind outside and his home back home. There was a bit of banal silence, and then the other two were gone.

The Cajun died that night, beaten to death in five minutes in the night behind the hotel’s service entrance, by three men who were never found. At the end there was steam coming off of him, but he was shivering, and the last thing he saw was a big dirty grey cat licking at his ankle. Skk, said Chenier. Skk.

It was only when the M.P.s entered the ballroom that Walter, Hamilton III, and Lukas realized that anything was wrong at all. They’d noticed that the Cajun was missing, and they knew he was in some kind of trouble, but they’d figured it was just going to be a little bit of pushing, something in the dark that any one of them might have confronted. Maybe he’d made friends with the sandy-haired boy and gone off to other pleasures. No.

The policemen separated them and brought them back to the station; there they were questioned, one by one: What are your names, and what unit are you from? Where have you been tonight? What have you been doing? Who was your friend? Who was he talking to at the bar? The three of them, Hamilton III, Lukas, and Walter himself, had hardly looked at the boy long enough to see him; they had heard the word nigger, and that had told them everything they needed to know. You didn’t see him? said the investigating officer to Walter. Your buddy goes out to fight three other men, and you don’t even see who it is? Why didn’t you go with him? Why didn’t you help him?

Walter was eighteen years old and had nothing to say, though a mad tear of dishonor slipped down the side of his nose. The drinking had long since left him, and their loss was strange; no one was supposed to get hurt until combat, and then only gloriously. No one was supposed to die upon dancing. Back at the base the three who were still alive had their last conversation. God damn it, said Lukas. Why’d the son of a bitch leave us? Why didn’t he ask for help? But all of them knew that they had done something too indecent to be washed away by sunlight or sobriety, or even the war to come. They had been careless and star-cursed, and Chenier had died.