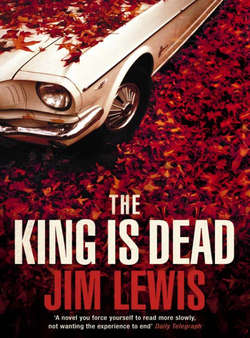

Читать книгу The King is Dead - Jim Lewis - Страница 5

PRELUDE

ОглавлениеThere was a woman named Kelly Flynn. She was born in 1720 to a Dublin banker, and raised in London, where her father had been sent to service a loan from the King. At court she met and married a Belgian furrier named DeLours; together they had nine children, and six of them died, four from disease and two through misadventure. One who survived, an intrepid boy named Henry (b. 1745), cut short his schooling to join the Army and was commissioned as an officer.

The Empire was widening into the subcontinent and there was a great need for resourceful men. Henry DeLours was clever and brave, and he was sent to Calcutta; while there, he met an Englishwoman named Elizabeth, the daughter of a fellow officer. He married her, and they produced five children. One of them, a daughter named Mary (b. 1770), returned to England to attend boarding school.

During a tour of Cornwall, Mary met an older man, a printer named Samuel Crown, who admired her, courted her, and soon won her hand. They returned to London, and their children were William, Theodore, Olivia, and Georgia, each following on the last by a little over a year. It was expected that the male children would join in their father’s business, but Theodore (b. 1790) was willful and wandersome, and as soon as he came of age he sailed for America, looking to make a fortune of his own.

For a time he clerked in a law office in New York. Each evening he went home to his small, dark room and wrote to his mother, describing both the faith he held in his future and the hardships that were testing it: debt, the dismissiveness of the men for whom he worked, the desolation he felt in this new, strange city. But he was frugal by way of defense, and he soon managed to amass a small amount of cash, which he used to purchase a few acres of land in Kentucky. He planted tobacco, labored, prospered, and within a few years he’d expanded his estate to some three hundred acres and two dozen slaves; by the age of thirty he had come to sufficient prominence to run for a local judgeship, and, with the help of some casks of whiskey that he had delivered to the taverns on the eve of election day, he won.

It was 1820, and Judge Crown was unmarried. Instead, he took a Negro woman, a slave named Betsey, who served in his house. He brought her into his bed almost every night—Apollo may not forgive me but Pan assuredly will, he wrote in his journal—and soon she gave birth to a son, a light-skinned boy named Marcus (b. 1821).

When he was a child, Marcus’s mother told him that his father was a house slave from up the road, but by then he’d already heard rumors that he was sired by the man who owned him. The cook would cluck about it and shake her head; the footman would tease him in their quarters at night; but he never sought to confirm or disprove the story of his origin. He didn’t dare, still less when Theodore at last found a wife, with whom he could have children who were legal and sanctified.

One midnight Marcus ran away from Crown’s farm, toward a legendary North. In his pocket he carried eighteen dollars, a sum that his mother had pilfered, penny by penny, from the household accounts, and which she’d given to him along with instructions to find his way to Ripley, Ohio. Under darkness, Marcus ran through fragrant fields; in morning towns, on broad bright days, he purchased food by pretending to be on an errand from some nearby estate, where the Master had a sudden need for a particular cut of meat, or oranges to make a punch, or bread to serve to an unexpected guest. By afternoon he would be sleeping in the cover of a thick forest or down at the bottom of a ravine.

In a week he came to the south bank of the Ohio River, which he followed east as far as Ripley. He could see the town on the other side of the water, but he was afraid to cross to it, and he waited at the riverside four days and nights, for what he didn’t know. In order to stave off hunger pains he slept as much as he could; in his dreams he heard women’s laughter. At last he was discovered by the freeman John Parker, who ferried him across the water and sent him along the Underground Railroad, northwest to Chicago. Fifteen days after leaving his home and his family, Marcus landed in the living room of a boarding-house on the south side. Not knowing what his own surname might be, he called himself Marcus Cash, and soon he was working as a laborer on the docks of Calumet.

Judge Crown’s farm began to falter, he owed money to every merchant within fifty miles, and bill collectors came by regularly to dun him. In the summer of 1840, Crown got into an argument with a barmaid over a glass of beer; he became belligerent, he became violent, and she struck him in the temple with an ax handle. He lingered on for a delirious few days, and then he died. To help pay off the debts he’d accumulated, his wife sold the slave Betsey, Marcus Cash’s mother, to a plantation in northern Mississippi.

By and by, Marcus Cash met and married a mulatto woman named Annabelle, eleven years his senior, a widow with three boys of her own. She had long soft braided hair, she could sing as sweetly as a flute, she cocked her hip and swept back her skirts. Within a year she was pregnant with a daughter they named Lucy (b. 1843).

Lucy was fair-skinned and full of feeling, and she needed more attention than her parents had to spare. What’s more, she was so much younger than Annabelle’s three boys that they scarcely thought of her as a sister at all, and as soon as she reached adolescence each in turn made advances on her. Marcus Cash walked in on the third and administered a whipping to him; but the incident suggested a danger that might recur on any wicked day, and soon Lucy was on her way to school in Philadelphia with instructions to study charm, to keep her legs pressed together, and to pass for white as well as she could, whenever it was possible.

When the War Between the States began, the Cash men watched and waited, and as soon as colored troops were allowed to enlist they joined up. Marcus died at Milliken’s Bend, when the tip of a bayonet tore his heart in half; one of his stepsons died of gut wounds received by gunshot at Fort Pillow, another of pneumonia contracted in the mountains of West Virginia, and the third of inanition while marching through Arkansas.

By then Lucy Cash had returned to Chicago, and after Appomattox she and her mother moved south to Memphis, Tennessee. At Annabelle’s insistence they pretended to be a young white woman with her aged and loyal servant—but in truth the older woman was nearly insane. Memphis had been in Union hands since the middle of the War, but she wanted to be within defaming distance of the former Confederacy: The two of them moved into a rooming house and the girl took a job sewing for a local tailor; and every evening Annabelle Cash would venture out onto a bridge over the Mississippi, where she would spit down into the water, and let the river carry her insult down.

Years passed—ten years, fifteen years. Lucy Cash had become a spinster, while her mother died a long, slow, puzzled death. The daughter was thirty-two; it was unlikely that she would find a husband, and a child was almost impossible to conceive. The daughter was thirty-three, thirty-four. And then one summer morning Annabelle awoke with a chill, complained briefly, and died, leaving Lucy Cash alone with her inheritance.

What happened then became a legend in Memphis: Lucy Cash moved out of the rooming house and into a small but elegant place on the north side of town. She hired a cook and a handmaid, bought chandeliers for the house and dresses for herself, and began to throw parties for young women and men. Within a year she was among the city’s most prominent belles, fifteen years too old but no one seemed to care; the yellow-fever epidemics of the 70’s had killed many of the younger women who might have been her rivals, and besides, the gatherings at her home were so elegant, so lively, the hostess was so charming and so duskily pretty. And in time she had her suitors: a pale and wealthy middle-aged man with a horse farm, a young rich gadabout, the blond boy born to a prosperous merchant, and the son of a minister, named Benjamin Harkness.

Having a keen sense of the mystery of salvation, Lucy Cash married the minister’s son. Her wedding took place just a few days before her thirty-seventh birthday, and exactly 280 days later the first of her four children were born; they would be Sally Harkness (b. 1879), and then Benjamin Jr. (b. 1880), and Charles (b. 1881), and finally Katherine Anne (b. 1883). The two daughters were prolific from a young age, producing a total of eleven grandchildren for Lucy Cash, none of whom she’d see or hold; she died of tuberculosis in 1892, revealing only on her deathbed, and only to her two boys, that she was one-half Negro.

In 1899, at the age of nineteen, Benjamin Harkness, Jr., went north to work for big steel, staying briefly in Philadelphia before being sent out to San Francisco to oversee the development of supply lines from the port. It was an unruly town, and being the grandson of a minister born to the privilege of wealth, he took full advantage of the sins of the Barbary Coast. By day he shuffled papers in his Russian Hill office; at night he gave syphilis and cirrhosis a run to see which could kill him first. In the end, the waves preempted both; stumbling home from a wharfside saloon late one night, he fell into the Bay and was drowned.

Charles Harkness was a dull and dutiful man, less ambitious and less lively than his brother, but his blood survived. He finished college, married a woman named Alice, and became a wholesaler of dry goods. Around Louisville, Kentucky, where he lived, they called him Gain for the number of his offspring: Charles Jr. (b. 1904), George (b. 1905), Diana (b. 1905), John (b. 1906), Robert (b. 1906), the twins Mary and Elizabeth (b. 1908), Patrick (b. 1910), David (b. 1911), and the second twins, Emily and Irene (b. 1913).

As soon as she was old enough to leave the house, Diana went north to New York—to study art at the city’s great museums, she told her father, but in reality to play amid its prosperity. Many nights she came home to her Riverside Drive apartment giggling and trailing black feathers from her boa across the lobby; many mornings she sat on the edge of her bed and wept—in despair at her loneliness, in pity because she was lost. Later, she would marry a bad man named Selby in a lavish church wedding; six months passed and she had her first son, Donald; a year and a half afterward she divorced her husband, not telling him that she was going to have another child. It was a second boy, Walter, born in 1925 in his grandfather’s house in Louisville, but cared for by Diana, until one day in 1937 when she stepped in front of a car on West Oak Street, was struck and thrown, lived on for three more days, and then passed away.

When Walter Selby was eighteen he enlisted in the Marines and was sent to fight in the Pacific War. In 1945 he came home a hero, finished college in two years on the GI bill, and then went to law school at Vanderbilt. Afterward, he settled in Memphis, the home of his great-grandmother, where he went to work for the governor of Tennessee. He met a woman named Nicole, he loved her more than love knew how; he married her and they had two children, a boy named Frank, and a girl, four years younger, named Gail. This book is their annals, twice-told and twofold.