Читать книгу Flash - Jim Miller - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

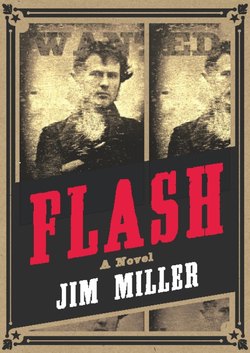

WANTED FOR GRAND LARCENY. BOBBY FLASH

Nativity, American; 25 years old; height 5 ft. 4 inches; weight

150 pounds; brown hair; smooth shaven; light complexion;

occupation dish washer, harvest stiff, bricklayer, etc.; two

gold upper front teeth; corduroy pants, brown corduroy hat;

tan button shoes, blue shirt. Member IW.W.., Holtville, Cal.

Was under Stanley at Mexicali and under Price at Tia Jua-

na-Mexican Revolution. Left here in the company of Gus

Blanco. He was with the IW.W.. bunch that took four horses

from Holtville and was mixed up in the robbery at Coyote

Well on the night of December 24th, 1911. He is a bad man. I hold warrant for his arrest.

Arrest, hold, and notify,

Mobley Meadows, Sheriff

Imperial Valley, Calif.

Dated: El Centro, Cal.,

January 2d, 1912

Who was Bobby Flash? I copied down the information and put the yellowed Wanted poster back in the folder. The next piece in the file was a mug shot of a young man staring hard into the camera with a defiant half smile that revealed what appeared to be a gold tooth. I looked at his face, under a mop of short but shaggy brown hair. His gaze was piercing and he had a fresh-looking scar under his left eye. I noticed that his work shirt was unbuttoned at the top and his overalls hung higher on his right shoulder than his left. On the back of the photo someone had written “Buckshot Jack, San Diego 1912,” but that had been crossed out by a different hand and replaced with “Bobby Flash, San Diego 1912?” I smiled at the thought of myself, Jack Wilson, being tagged with the nickname “Buckshot,” but I was more intrigued by the correction. Was this really Bobby Flash? I stopped for a moment, lost in thought. What drew me to him? Perhaps it was the vague stories about my “crazy commie great grandfather” that my mom would toss off when she was assailing my father’s side of the family. They had always resonated with me—just not in the way she had intended. And, perhaps it was just a flight of fancy, but I thought Flash looked a bit like my son Hank thrust back in time (minus the gold tooth). OK. Enough already. Maybe it was just the name, Flash.

I checked the time. It was 4:30. I looked up and saw that the librarian was still occupied at the front desk so I continued to inspect the file. The next piece was another Wanted poster:

WANTED FOR GRAND LARCENY AND ROBBERY. GUS BLANCO OR BUNCO

Nativity, American; age 30; height 5 ft. 8 in.; weight 157

pounds; brown hair; no beard; small moustache; gray eyes;

chunky nose; red cheeks; occupation bronco buster and cow

puncher; slightly stooped shoulders, upper lip hangs over

lower, walks like a man stove up from riding horses; left

here wearing blue overalls and black felt hat. Is a member

of I.W.W. [agitator], canvasser for Industrial Workers of the

World. Was in Mexican Revolution, first under Berthold at

Mexicali, and at Alamo under Mosby at Tecate also un-

der Price at Tia Juana in C Troop. Will probably find him

around IW.W.. halls and men. He is also in the bunch that

took the horses from Holtville and started for San Diego.

He was the leader of the I.W.W. men here and is an all around

bad man. Anything you may do to get this man will be very

much appreciated. I hold warrant for this man.

Arrest, hold and notify,

Mobley Meadows, Sheriff.

Imperial County, Calif.

Dated: El Centro. Cal.,

January 2d 1912

So Bobby Flash was with Blanco and the Wobblies who flooded into San Diego in 1912, the year of the free speech fight. Except this band appears to have been fleeing after the Mexican army took back Tijuana, and the United States sent in Federal troops to round up the American revolutionaries. Many were killed, hundreds arrested, but somehow Flash and Blanco slipped out of the trap. By March, the I.W.W. would call in an army of thousands of bindlestiffs and professional agitators to join them in the battle for free speech, but it looked like Flash and Blanco were there before the main action started. It had been a blood bath, and I thought a story on the centennial anniversary would be great, but I needed an angle and perhaps these two outlaws would provide it. I looked for another mug shot but, unfortunately, there was no picture of Gus Blanco. What I did find was a picture of the lawman, Mobley Meadows, Imperial County’s first sheriff. He didn’t fit the mold of a TV western tough guy. Instead, he was a patrician-looking fellow, almost effete—the kind of guy who liked to call people “bad men.” Just as I was about to dig through the rest of the file, the librarian, a balding, pudgy, middle-aged man, walked over and told me it was closing time. I managed to talk him into making me a couple of photocopies of the Wanted posters and then headed out of the archives room past a cluster of homeless men outfitted in army surplus and Padres giveaway gear who were lingering by the restroom, waiting to be prodded over to the stairs and out onto the street for the long hard night.

Out on E Street, everything was vivid as it always is after your head has been stuck in a stack of papers for the better part of the afternoon. I stopped and noticed, for the first time, the lantern in the center of a circle of mosaic tiles on the sidewalk in front of the library, and the sailing ship at the heart of the San Diego seal a few steps away. Walking past the stout fellow packing up the coffee cart out front I nearly bumped into a pair of sleek Italian women, language school tourists most likely, on their way to the Gaslamp District. They both had long, lush black hair and were chatting animatedly in their native tongue. One of them threw her head back when she laughed and raised her arms in the air like a conductor. A car rolled by with a Radiohead song blasting and another with radio news. “Today, the markets fell on reports…” was all I heard before it faded into the evening. The sky was dark blue beginning to bleed red as I crossed the street and begged my way past the security guard at the post office door so I could check my mailbox. Once inside, I hustled over to the wall of little copper squares and quickly did my combination to find some junk mail and a letter from my son. I shut the box and stopped for a moment to look up at the ceiling of the beautiful old WPA building. Like the funky fifties library, it is one of San Diego’s few remaining nods to history with its simple yet elegant modernist design, the light blue molding framing the ceiling, a long rectangle with a row of lamps lining the center. It was quiet like a church with the crowd gone and I wished I could stay and read Hank’s letter there, but the guard was already on his way over to put an end to my reverie.

I put the letter in my back pocket, strolled down E street to 5th Avenue, turned left and walked half a block to where The New Sun had just opened up its office on the second floor of the Hub-bell Building, above a wine bar. It was a gorgeous late-nineteenth century space—1887, to be precise—that we’d never be able to keep, but it was great for the time being. My boss, Neville, the owner and editor, was a solid guy, a trust-fund radical from a conser vative family who was willing to spend a lot of money for a while in order to irritate his family. Once things got close to affecting his personal bottom line it would be over, but, for now, it beat the alternative—unemployment. I had burned all my other bridges in town.

I started back with the SD Weekly, a sad imitation of an alternative weekly owned by a pugnacious Christian conservative who reveled in irritating the powers that be as long as they were his personal enemies. He was an ex-Marine who still wore a crew cut. He had a face like a bulldog and sported a bowtie and pants that were always a bit too high. “Sarge,” as all the writers called him, could be nice, but he had a mean streak. Thus he loved my pieces exposing land deals that benefited the business elites who had funded the campaigns of half the city council and the mayor. It turns out that this wing of the local Republican Party was at odds with the “values” folks. So I went after the money people. This led to a brand of quixotic muckraking that Sarge thought was perfectly fine until I started going after some of his sacred cows. The piece that got me fired was an exposé on an education reformer who went to the boss’ church and turned out to be a convicted pedophile. I called it, “Reform, This.” He thought it was “tasteless” and replaced me with a guy who went after the labor unions instead, as the city’s only daily, the right-wing Imperial Sun, always did.

My next stop was The Independent, a former punk rock mag that was trying to compete with the Weekly. The editor there, Billy Zero (he went by his pen name), was a well-meaning but not particularly sharp fellow who thought of himself as the coolest guy in town. Zero answered directly to the corporate office that ran about twenty other “independent” weeklies across the country, but he had a tattoo and a little earring so the alternateens he hired to write rock reviews for nothing thought he was hip. I treaded water there for a few years as a kind of utility infielder doing stuff on culture and politics without much problem. I did a piece on the owner of the Weekly and his connections to the Christian right, anti-abortion, and anti-gay rights crusades and Zero loved it. I wrote a column called “Lotusland Blues” for a year and pissed off half the city. Zero loved that, too. Things were looking up—for a while.

What got me in trouble with The Independent was a story I did called “Cool Gentrification” about how the last old bars and single-family businesses were getting pushed out of downtown by “hipster capitalists,” a few of whom frequently advertised in the paper. That piece led to a chat with Zero over beers at the Barge, the oldest bar in the city, which used to be a haven for fishermen and union factory workers before those industries largely vanished from town. Now the old scrap yard and dingy boat dealerships that had surrounded it had been replaced by high-end condos. Bye bye blue collar, hello hipsters! In any event, Zero bought me a beer, sat down next to me at the bar, ran his hand through his spiky hair, and said, “Jack, I think you are getting too predictable.”

“Predictable?” I asked, staring at him as he squirmed a little on his barstool.

“Yeah, Jack, all the ‘fuck gentrification’ stuff is getting old,” he said with a whiff of condescension while refusing to look me in the eye.

“How so?” I queried deadpan, but suspicious. “I thought we were an alternative weekly.”

“I don’t know,” he said trying to look caring as he delivered a dose of what he seemed to think was tough love. “Maybe the alternative to alternative is alternative.” He looked down at his tattoo. I laughed once I realized he was serious.

“Zero,” I started, unable to help myself, “that’s the dumbest fucking thing I’ve ever heard. You can fire me if you want to, but that’s just stone cold stupid bullshit.”

“You can be defensive if you want to,” he said, assured of his wisdom. “But I think you should be open minded and think about what I said.” He got up and left the money for the beer. I stayed and ordered another. Later that night, I got online and did a little research on Zero. I found an article in an industry rag where he said that, “We may come off as more left than thou, but all the while we’re busting our asses to please our advertising base.” It turns out that the hipster capitalists had flooded the paper with complaints and threatened to pull their ads if the tone of the paper didn’t change. If Zero had been straight with me, I might have considered his plight with the corporate office, but his pathetic advice had pissed me off. I decided to write myself out of a job, make him fire me like a good old-fashioned “uncool” boss.

I began by doing a story on the hideous architectural malpractice of one of The Independent’s main advertisers. Entitled, “A Sick Joke on the Avant Garde,” the piece included pictures of some of their marquee condominiums and mocked their stunningly ugly design. My “Best Of ” list included “Best Santa Fe Style Stalinist Block Building,” “Best Postmodern Prison Bunker,” “Best Retarded Sailboat-Themed Monstrosity,” and a special category for “Best Unintentionally Cartoonish Mural Art on a Live/Work Space.” They lost the ads. No comment from Zero. One of the alternateens got a TV show about local rock bands on the local FOX News station, and I did a column entitled “OK, Punk Really is Dead Now.” Still, I was gainfully employed. Only my final shot, “Alternative, Inc.” featuring Billy Zero’s quote in the industry mag and a discussion of the parent corporation’s other connections, which included lots of unsavory, uncool things like toxic waste dumps and union busting law firms, did the trick.

Eventually The Independent’s parent corporation outsourced the local reporting to India, I kid you not. The “reporters” watched the City Council meetings over the internet live and Googled their sources. They even got rid of the underpaid music reporters by holding a weekly contest on the paper’s blog called “Concert review of the week,” where an unpaid blogger’s take on the big show took the place of an underpaid staffer. Album reviews came off the wire. Mercifully, the parent corporation’s experiment with outsourcing local news and hip commentary died, and they shut down the paper, but give it time. Oh brave new world with such creatures in it…So anyway, that’s how I ended up here at The New Sun tossing copies of century-old Wanted posters on Neville’s desk.

“Let’s find out who Bobby Flash was,” I said without any introduction.

Neville picked up the copies and read them studiously, pushing his little round glasses down his nose a bit and nodding slowly. “Do you want to do a quick piece or a feature? And why not Bunco? He was the leader of the group wasn’t he?”

“Well, the hundred-year anniversary of the free speech fight is coming up so I think it merits a series.” I said, pushing the envelope as always. “And we’ve got a picture to go with Flash’s name. Plus, I’m drawn to bit players. The folks in the background are always more interesting, no?”

“And that’s important to you and a handful of people,” he said without looking up.

“I’ll make it important.”

He smiled and looked up slowly. “Start doing it and talk me into it later. In the meantime, I’ve got a few other things for you, one on something big in Tijuana. The other is local. You can work on Bobby Flash for the long haul.” He handed me a folder.

“Fair enough,” I said looking over a letter in the folder that Neville had just handed me. It had been written on behalf of the women in a Tijuana neighborhood who lived down the hill from an abandoned maquiladora. When the rains hit, the waste from the plant flowed down into the dirt streets by their homes. Bad things were happening, and nobody was paying any attention. Bobby Flash would have to wait until next week.

I said goodnight to Neville and headed down the stairs out onto 5th Avenue. There were a few couples sipping zin in Vineland just out the door. I headed up toward Broadway to the bus stop, pausing at 5th and E for a moment to try to imagine the soapboxers stirring it up a century ago. The fancy bar and grill on the corner made the job tough, but I thought for a moment of Bobby Flash hopping up to say, “Fellow workers and friends,” before being dragged off by the cops. Or maybe he got into a good little rant before they could grab him: “The Working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace as long as hunger and want can be found among millions. How come the bosses got all of the good things? You tell me why.” I smiled as a pack of suits strolled by to hit Ostera, a “Watergrill.” Crossing E, I made my way past the new restaurant of the week, a pawn shop, a check-cashing place, and the last remaining cheap eats joints before I hit Broadway and just caught the bus that would take me up to Golden Hill where I lived in a flat behind a big old house. I dropped in my fare and walked to the back. In the dirty white light I saw the tired, after-work faces of cashiers, janitors, secretaries, security guards, and the homeless men who rode the line like Bartleby the Scrivener, preferring not to leave until they were kicked off at the end of the route.

Neville never told me what to write or even what the lead was, he just handed things over to me like an old-school newsman in a thirties movie. I loved that about him. I sat down and looked over the other item in the folder he’d given me. It was a copy of an email the paper had received from a Marine at Camp Pendleton whose buddy had shot himself the week before. The local TV news had done the “fallen hero” bit but there was some nasty stuff about his experience in Iraq that nobody had mentioned. The Marine wanted to talk to somebody. I looked up at the reflection of my fellow passengers in the window. Indistinct shapes, blurring together. The bus rolled by Church of Steel Tattoo, Chee Chee, El Dorado, and a block that had been leveled for redevelopment. Just then I remembered my son’s letter in my back pocket. I took it out and read:

Dad,

Just have a few minutes to get this out before work. Things are going OK with my classes but none of them are very interesting. Other than the job thing it’s hard to see the point. English is boring, math tedious, and political science lame. I’ll try to stick it out as you advise but other than the “better job” thing there’s not much I’m learning that I couldn’t learn on my own. I know you said not to follow your example, but you never finished school and you have a job, right? Not giving up yet, I’m just saying I think you did all right, no matter what that asshole Kurt says. Maybe it’s just having to stay in that house to save money. Shit, I’m in my twenties! Mom and Kurt are fighting all the time and it gets me down having to listen. Sorry to dump all this on you, but I know you’ll understand. I’ll be OK. Off to serve coffee to the masses.

Love, Hank

P.S. How ’bout a visit sometime? Or me down in SD?

I smiled, shook my head, folded the letter up carefully, and put it back into the envelope and then in my back pocket. Hank always sent his letters to the PO box since I moved a lot. He and a few select friends were are the only people who have that address other than the junk mail people who seem to be able to ferret you out no matter where you try to hide. I insist on letter writing; it’s my nod to a dying art and the notion that fast isn’t always better.

The bus was lurching up the hill toward my stop and I stared out the window into the night at the lights in the front windows of apartments and houses—strangers doused in the dull glow of TVs or sitting down for an evening drink. I got off the bus when it hit 25th, to head to my flat. On the way there I nodded to the doorman smoking outside the Turf Club and glanced through the window at a few solitary faces staring at laptop screens in the Krakatoa Café. I lived behind a Victorian house that the owner had chopped into four claustrophobically small units. My place had a postage-stamp lawn and little porch outside the studio. I had made it—I was in my forties and still doing the work I did when I was in my twenties. And my kid seemed bent on replicating my mistakes. If my mom’s stories about my “hobo” ancestor were correct, maybe it was in the genes.

Long ago I had been relegated to weekend visits, so I was the “cool dad.” It was true, Hank’s stepfather Kurt was an asshole, but unfortunately that seemed to be sending Hank the message that people who could support themselves adequately were all assholes. Partially true perhaps, but a dangerous generalization. Trisha, Hank’s mother, had left me back when he was a baby. I had been working for the LA Scene, an upstart alternative weekly in the days before they were all bought up by media corporations. Anyway, I had been out covering a Jane’s Addiction show at the Howl club down by McArthur Park and came home to an empty apartment and a note: “Sorry Jack, I can’t do this anymore.” By “this” Trisha meant living on my shit wages with a baby. She had been a hairdresser, but quit when she got pregnant, to my surprise, apparently expecting that fatherhood would transform me into a proper provider so she could stay at home. Instead, she got a live-in boyfriend who had to leave her alone at home a lot so he could bring back an inadequate paycheck.

We’d been living in a cheap apartment in the San Fernando Valley with a banner perpetually strung on the side of the building, which read “Move In Now!” Perhaps the owner thought he needed to advertise endlessly because the combination of the 24/7 smell of greasy chili burgers emanating from the Tommy’s next door and the pungent odor of late night hops from the Anheiser Busch Brewery across the street drove everyone who could afford to leave out of the complex. None of our neighbors spoke English, a fact that Trisha frequently commented on, along with the 5:00 AM Norteño music that the neighbors blasted from their pickups as they took off for work. “It’s a hard life,” I’d tell her.

After she left, she moved in with her mother, who consistently referred to me as “the loser” during my son’s formative years. This made for a painful and ambivalent childhood for Hank. Nonetheless, the harder Trish and her Mom tried to push him away from me, the more he pulled his way back. Even as a very young boy Hank would draw pictures of “Daddy at a music show” or “Daddy writing.” It drove them fucking crazy and I loved him for it.

A couple of years after Trisha moved out, she hooked up with Kurt, an ex-frat boy from USC who had a job in real estate. They got married and Kurt set about ruining Trisha’s life in a whole new way. He had affairs, berated her in front of Hank, and dissed me constantly. Kurt was an all-star. His saving grace: money. Hence Trisha was long-suffering and materially comfortable in West LA.

Trisha and I met back in 1987 at Al’s Bar, the legendary punk spot in the loft district of downtown LA where a lot of artists lived. It was walking distance from the Atomic Café on the edge of Little Tokyo. I loved Al’s, both for the good music and for the fact that it was a place where Bukowski used to drink. The neon sign behind the bar said, “Tip or Die.” I was there that night to cover a tiny theater troupe’s version of Kerouac’s Tristessa. They put the show on in the alley behind the bar and an audience of a dozen or so people sat on the same kind of metal bleachers they have at little league fields. It was a dramatic adaptation of the Kerouac novel about Jack and his friends in Mexico City, and Jack’s brief dalliance with a soulful, tragically beautiful prostitute, whose name means “sadness.” The actors entered stage right from the back door of the bar and did a decent job of invoking the beat mood with no set, no costumes, and no music. Spare, earnest, and bittersweet. My review was entitled, “Beat in the Alley.”

I remember spending a lot of time during the play staring up at a high rise framed by the narrow alley and glancing over at Trisha. She was dressed in all black (a sort of uniform then) with long hair dyed bright red. Her eyes were blue-green and she had a sweet smile that lit up her face. After the play, we both stayed to listen to a cowpunk band from Austin, Texas, named Hillbilly Tryst or something like that. I bought her a beer and we talked about the play, about the Beats, about music. We agreed that life was tragic. She let her friends go home and left with me, strolling down the dark street lined with sleeping bodies under dirty blankets or flattened cardboard boxes. When we got to my car I kissed her softly and gazed into her alabaster face. We looked up at the crescent moon above the looming skyline. The whole city was mine, the big wide world. I was in love. We went home together, and it was all good, for quite a while.

Back then, Trisha rented a room in a big house up in the Hollywood hills from the guy who ran The Grave on Hollywood Boulevard. Actually she chipped in for his rent. The place was really owned by a nearly senile old woman in the valley who lived there when she was a kid. She hadn’t done her homework, and Zane, the Ghoul, and Trisha were getting the whole two-story house with its nice yard overlooking a canyon and a view of the Hollywood sign for a mere pittance. Zane, who managed the club at night, had a day job with the Water and Power Company so he more or less had his shit together. The Ghoul, on the other hand, played in a local band called Night of the Living Dead and was a full-on junkie.

By this time in my youth, I had grown my shaggy hair out to about shoulder length and usually never wore anything fancier than jeans, a t-shirt, and black converse sneakers. Trisha used to make fun of my lack of fashion sense. That said, the Ghoul, who rarely bathed, never washed his clothes, and made little effort to conceal his track marks, made me look like a GQ cover boy. He usually lounged around the basement room in a leather jacket with no shirt underneath and boxer shorts. When I came over Trisha and I would do everything we could to avoid being drawn down into his lair. Suffice to say we never chased the dragon.

The rest of the place was fantastic. Zane, a manic Aussie with a thick mane of long red hair, had an impressive collection of Marilyn Monroe photos that lined the hallways upstairs: Marilyn in Playboy, Marilyn in Bus Stop, Marilyn pouting, Marilyn teasing, Marilyn tragic and innocent, Marilyn in death. He and his girlfriend, Cat—an aspiring actress who had her own place but basically lived with Zane—had filled the living room with vintage furniture carefully selected from stores on Melrose—late-fifties and early-sixties Moderne. The end tables of the leopard-skin couch were littered with copies of Screw, The Hollywood Reporter, and BAM.

Trisha worked on Melrose in a salon called the Union Jack, which the owner had decorated with British rock posters, Sex Pistols, Clash, The Who, etc. Whenever I could, we’d meet for lunch or for drinks after work. We scoured used-record stores for hidden gems, had lots of coffee, and looked through second-hand shops. During that period, Trisha never said a thing about money. We just talked and made love and went out to see music. She read a lot so we rapped about books mostly. We’d both started and then stopped college and figured we didn’t need to pay somebody to tell us what to read. She liked the Beats, but also Anaïs Nin, Virginia Woolf, and Sylvia Plath. Thus the talk had a lot to do with sex and death and suffering and angst and carpe diem. One thing Trisha didn’t share with me was an interest in politics. I just assumed we were in tune at a basic level.

Sometimes we’d go downtown between the Nickel and the Garment District to Gorky’s on open mic night to listen to bad poetry for laughs. Gorky’s was a hip Russian-themed cafeteria that served borscht, brewed their own beer, and had music, art, and poetry every week. Before I met Trisha, I had a brief flirtation with poetry. I read a lot of Bukowski and wrote a few pieces about waking up with a bad hangover and hating the world. When I went to my first open mic night at Gorky’s I discovered that everyone else had read a lot of Bukowski and had a lot of hangovers. We all sucked. After that realization, I still liked to go to Gorky’s, but solely for amusement. One night, Trisha and I almost bust a gut laughing after an English grad student from USC read a poem about a roach crawling on her IUD. The woman wasn’t pleased with our response and flipped us off. Of course, this only made us laugh all the more.

Sometimes there would be surprises though. One evening, after a series of poets who overcame their lack of skill with the language by yelling at the top of their lungs, a petite young woman in an X t-shirt nervously came to the mic and read an elegy called “Anonymous” about a man who died on the street outside her loft downtown. It was a cry for those who die unknown in solitary rooms, a howl for the utterly forlorn. It was so stark and beautiful after what had preceded it that quite a few people, myself included, were moved to tears. It was beyond irony, for once.

I was pretty busy then with the LA Scene. I did a whole series on the culture of the homeless men who lived by the Los Angeles River. I spent a week sleeping under bridges and hanging out in homeless camps interviewing men around bonfires. One group I found was a band of scavengers. They sold scrap metal on the black market so they’d rip it off of anything they could find and bring it in to the yards. It was a good enough gig to get some of the guys out of the camps and into hotel rooms in the Nickel. Some, though, thought that rent was a waste of coin and preferred to live alfresco. I remember one night in particular. It was February during a cold snap and I was sitting by a fire under a freeway bridge sharing a few bottles of wine and cheap whiskey with twenty men. There was a kind of code in the camps that reminded me of those scenes in The Grapes of Wrath where folks on the road would help each other out sometimes. Some of the veterans remembered the old days too. That disappeared when crack hit the scene and people started killing each other for pocket change. A few months after my series, the LA Times did a similar thing, but I never got a call or a credit from anybody.

Speaking of crack, I also did a story on the “Contra Cocaine” posters put up all over the city by guerilla poster artist Robbie Conal. The poster featured a skull in the tradition of the calaveras in Mexican Day of the Dead art, but this one was wearing a pinstriped suit with a camouflage background. The heading provocatively made the connection between the Reagan Administration’s support of the contra insurgency against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua with the little known fact that the contras were flying coke into the US with the help of the CIA. Overnight, 10,000 of these posters went up all over the city, from the alley near my studio apartment in Venice to telephone poles and other public spaces in LA and in seventeen different American cities. I got a photographer to take some greats shots of the posters in Skid Row downtown and interviewed Conal and a local professor at UCLA about the significance of the gesture. The CIA-funded drug runs during the explosion of street gang warfare in LA was strong stuff and despite CIA denials, it turned out to be true. I followed up that story with a piece about Salvadoran death squads chasing down and murdering leftist refugees in Los Angeles. One of my sources got killed before the article went to press. It was one of those epiphanic moments in my life when I realized that anything, no matter how menacing, was possible.

So I was completely immersed in my life as an underpaid jack-of-all-trades, if you’ll pardon the pun, for the LA Scene, not paying much heed to the future. When I wasn’t crashing at Trisha’s house in the Hills, she was staying with me at my studio in Venice. We took walks by the canals to feed the ducks and bemoaned each time a McMansion took the place of a cottage. We strolled down the boardwalk on lazy afternoons watching the fire jugglers, listening to pitches from religious cranks, and stopping to be serenaded by troubadours on roller skates. We’d buy books in Small World, and read over beers until sunset. The only bad thing that went down during that period happened back at Trisha’s place, when a friend of the Ghoul’s OD’d in the bathtub during one of the gatherings in what was an endless stream of house parties. There were tons of people there, and when Zane discovered the body he cleared the house, screaming at everyone to “get the fuck out” and insisting that the Ghoul and his buddies drag the guy’s body out of the house. I almost got in a fight trying to persuade them to call an ambulance. Trisha packed up her stuff that night and moved in with me. Within a month she was pregnant.

To be honest I was surprised she wanted to keep the baby. I had told her that it was her body and I’d be there either way. She thought about it and decided to have the kid. “Because I love you,” she said. As you might expect, I was scared shitless at the prospect, but soldiered on. Trisha quit her job, and we moved to the Valley to be near my mom’s house, as Trisha’s family was not too keen on the idea of her having a kid “out of wedlock.” I was surprised people still talked that way. In my eyes, Trisha just got more and more beautiful when she was pregnant. She let her hair, naturally black, grow out, and she was radiant. I would write up my pieces and go get her snacks when she needed them. I was with her in the hospital and got up at night to feed little Henry (named after Henry Miller and the “Hank” character in the Bukowski stories).

During this period, there was never any discussion of Trisha being unhappy. Quite the contrary—I remember getting up to feed Hank (Trisha pumped breast milk in bottles so I could do some late night duty), and I walked with him cradled in my arms out onto the steps in front of our place. Despite myself, I got lost in the wonder of my baby boy. The fragility, the improbability of life. I could smell the hops cooking across the way and it was deep and sweet in the hot summer air. At that moment I swore that I’d try to be there for him for the rest of my life. Trisha came out and kissed me on the cheek and we looked at the moon. I’d never felt more love or more peace than in the ocean of it that subsumed me at that moment.

The next night, I drove over the hill to cover the Jane’s show at the Howl. I wandered around the gorgeous hotel lobby, went into a room taken over by dozens of huge screens featuring a Burroughs-like cut-up of random black and white stills, some of iconic images like Robert Frank, others looked like family photos, then some blurry color footage from a handheld camera. It lost my attention and I went over to the bar and bought a vodka soda. In the next room, some guy dressed up like Jesus, with a big cross strapped to his back, was crawling around on all fours begging for a gin and tonic. This got old fast so I walked back out to the top of the big staircase in the lobby. It was an elegant setting, a fitting backdrop for Mae West in her prime. By now it was littered with tall, sexy girls, posing by the railing, practicing various stages of ennui. A few looked high on H. They were the kind of women who never gave me the time of day and I was out of the game now anyway.

Jane’s Addiction played in another big room that looked as if it had once been the hotel’s chapel. The crowd was jammed in tight, flesh against flesh. You could feel the rush of anticipation surge through the room when the band came on stage. They opened with a hard driving version of “Pigs in Zen” and Perry Farrell was in top form, prancing around the stage theatrically and leaping in the air. Everybody went nuts for “Jane Says,” but I preferred their cover of the Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil” and the way Farrell’s voice poured out longing when they closed with “I Would For You.” It made me think of Trisha, and I just wanted to get home. I walked out past the lounging and posing and desiring crowd to my beat-up Mustang. I popped in a Los Lobos tape and glanced up at the downtown skyline as “One Time One Night” came on, and I rolled onto the freeway to head back to the Valley. When I got home, I found the note in our empty apartment. It was a warm summer night and the thick smell of hops and hamburgers made me want to throw up.