Читать книгу Flash - Jim Miller - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

I showed up at The New Sun early in the AM to call my contacts. Neville was already there, working on a review of a string quartet that’d opened a new classical music festival in La Jolla. His politics were very left, but he had a Ph.D. in the Humanities and was extremely well-versed in the arts, opera, and classical music. This was a huge boon for our anemic advertising budget, since we had the best coverage in town and that gave us some cultured readership, which appealed to a handful of advertisers for galleries, wine shops, record stores, travel agents, etc. So the wine and cheese crowd and “adult industry” (porn is the evil twin of every good muckraking weekly) kept Neville’s trust fund from being pillaged. Neville ignored my warm greeting, so I left him to his work and poured myself a cup of his coffee before hitting the phone. I had to leave a message for the Marine, but got a hold of Ricardo Flores right away. Ricardo was the spokesman for a coalition of labor and human rights groups. Las Madres Unidas, the women from the neighborhood downhill from the maquiladora, was part of Justicia para Trabajadores, the larger group that he helped run. Ricardo would meet me just over the border at 4:00 if I could make it. I could. It was still early so, with no word yet from the Marine, I decided to go back to the library to finish looking over the I.W.W. file I had been pulled away from yesterday evening. I had Bobby Flash on my mind despite my other obligations. Neville ignored me when I waved to him on the way out.

Back at the archives, I asked the librarian, the same pudgy guy, for a file on the free-speech fight and he brought it over to me glumly. Mostly, it was a fairly haphazard selection of newspaper clippings from 1911 and 1912. I read a pair of dueling rants: The Union editorialized in favor of the vigilante attacks on the Wobblies and their supporters, while The San Diego Sun attacked the owner and editor of the Union, John D. Spreckels. One of the attacks was entitled, “Put This in Your Pipe and Smoke it Mr. Anti-Labor Man.” In it, the writer decried the way Spreckels sought to run San Diego like General Otis of the LA Times had run Los Angeles—as a petty dictator. More to the point, The Sun argued, it was clear that Spreckels was most upset about being taxed for “occupying the streets with his railways.” I took a few notes and remembered having read that one of the key things that preceded the free speech fight was the effort of the tiny San Diego I.W.W. Local 13, which had only fifty members, to organize the Mexican workers on Spreckels’ street car lines.

Unlike the local AFL unions who wouldn’t even try to organize Mexicans, blacks, or Chinese workers, the Wobblies welcomed everyone—even unskilled migrant workers. The Wobblies were the only American union to oppose exclusion laws and organize Asians and other workers like the Jews, Catholics, and recent immigrants frequently ignored by the American Federation of Labor. The Industrial Workers of the World was born out of the fires of Colorado mining wars, and the Wobblies thought of themselves as revolutionaries. They rejected contracts, believed in direct action, were suspicious of political organizations, and mixed anarchism, syndicalism, Marxism, and an inverted form of Social Darwinism freely as their rough and ready membership thought of theoretical distinctions as useless nitpicking. (Having covered my share of endless leftist political gatherings, a hostility to useless nitpicking was a sentiment I could get behind.) Believing in “One Big Union of All the Workers,” they thought that their form of organizing would eventually lead to a huge general strike in which the workers would take control of the means of production and end the rule of the bosses. They were forming the structure of a new society in the shell of the old. Unrealistic, as it turned out, but a good thought. In San Diego, by hitting Spreckels’s streetcar franchise they went straight after the interests of the richest man in town and scared the shit out of the powers that be. I liked that.

For the Wobblies, the whole street-speaking thing was more about organizing than it was about some abstract idea of the Bill of Rights. By standing on a soapbox in the middle of the street they could reach out to the floating unemployed population, disgruntled workers, and others receptive to their message, and educate them about the interests of all workers or agitate them to join a given fight. The goal was to turn those on the outskirts of society away from shame and defeat, and toward anger. They wanted to turn “bums into men.” I looked at a picture of a scruffy crowd listening to a soapboxer at 5th and E, and smiled as I imagined the present day parade of bistros, wine-bars, and trendy meat markets. When I had first visited San Diego back in the eighties, downtown had still been a sailor town of dive bars, strip joints, porno shops, greasy spoons, flop houses, and mom and pop shops. Back at the turn of the century, the Gaslamp was called the Stingeree and 5th and E was Heller’s Corner. The Stingeree was where most of the working-class whites, white-ethnic immigrants, Chinese, and Mexicans lived. It was full of shops, saloons, cheap hotels, gambling houses, opium dens, and prostitutes. Middle- and upper-class ladies used to complain about having to pass by the soapboxers and the grimy throng of workingmen and other ill-clad, shabby-looking characters. All in all, it sounded a lot more fun back in the day than it is now—unless you’re looking for a bad cover band or an overpriced cheese plate.

What kicked off the events that led to the free speech fight was an incident on January 6th, 1912 in which an off-duty cop and real estate man tried to drive his car straight through a street meeting. The crowd rocked his car and slashed his tires even though the Wobbly speaker warned them that this would just give the police an excuse to break up the meeting, which they did. I have to say that after being almost hit by a car, it might be tough for me to show restraint too. I’ve been known to flip off a heedless driver or two in my day, but that’s beside the point. Anyway, after that, Spreckels and his crew saw their opening and pushed San Diego city authorities to pass an ordinance banning street speaking in basically the entire Stingeree District in February 1912. Of course the ban irritated not only the I.W.W. but also a whole range of other folks including the AFL, Socialists, religious leaders and civil libertarians who formed the California Free Speech League to challenge the ban. The I.W.W.’s response was to flood San Diego with thousands of protesters, and when the first waves of the Wobbly army hit town, city authorities passed a “move-on ordinance” that gave police wide powers to break up street meetings and harass “vagrants.”

The Wobblies were pretty disciplined and did everything they could to avoid violence because they knew the cops generally welcomed an excuse to bust heads. San Diego police, however, emboldened by the new laws and egged on by the city’s bosses, didn’t hold back. They waded into crowds with batons flying and beat prisoners all the way to jail. They used fire hoses to knock protesters off their feet, and filled the jails with Wobblies. In jail, the brutality continued with the murder of sixty-five-year-old Michael Hoey, who was savagely beaten by three cops, kicked in the groin multiple times, and left to die on the cement floor of an overcrowded, rat-infested cell. Outside the pen, they shot another Wobbly named Joseph Mikolasek in front of the I.W.W. headquarters. Still, a tough bunch, the Wobblies didn’t get scared off. They kept flooding into town, packing the jails, and singing until it drove the police crazy. In one article I found a quote where a cop whined, “These people do not belong to any country, no flag, no laws, no Supreme Being. I do not know what to do. I cannot punish them. Listen to them singing all the time, yelling and hollering, and telling the jailors to quit work and join the union. They are worse than animals.” Great stuff, I thought.

When police brutality didn’t work, the city fathers ended up resorting to vigilante terror. Working at the behest of the elite, most of the vigilantes were scared middle-class merchants, aspiring real estate men, clerks, off-duty cops, and otherwise-respectable thugs who were just looking for blood sport. This reminded me of the stuff that happened with the cops around the time of the LA riots. Some of the elites such as George Marston and The Sun’s owner, Scripps, didn’t support the I.W.W. but did support the idea of free speech. Most, though, were in line with the reign of terror. As the Union editorial put it, “Hanging is none too good for them and they would be much better dead; for they are absolutely useless in the human economy; they are waste material of creation and should be drained off into the sewer of oblivion there to rot in cold obstruction like any other excrement.” I think it’s safe to say they weren’t fucking around. So a vigilante army of about 400 men was formed. They met a trainload of incoming Wobblies and beat and tortured 140 men, making them run the gauntlet before sending them bleeding on their walk back to Los Angeles.

I looked over several reports of Emma Goldman’s visit to San Diego. Most people who’ve ever heard of the free-speech fight also know the story of how Goldman, the famous anarchist, was driven out of San Diego by quite a welcoming committee. Met at the Santa Fe depot by a snarling mob of “ladies” screaming for her blood, Goldman was ushered to the US Grant Hotel where the mayor denied her the opportunity to speak to an angry mob in the park across the street below. While this negotiation was taking place, a crew of thugs kidnapped her lover, Ben Reitman, and drove him out to near the Peñasquitos Ranch to meet a pack of vigilantes who proceeded to make him kiss the flag and sing “The Star Spangled Banner.” Think of that the next time you’re at a ballgame and I bet you won’t sing. They stripped Reitman, viciously beat him, jammed a cane up his bunghole, nearly twisted his balls off, and branded I.W.W. in his ass with a lit cigar. He was then tarred and feathered and sent north on foot. What interested me, however, was not the story of these legendary anarchists, but the unknown stories of those who were lost to history.

I kept skimming through the articles, some of which I’d seen quoted in books, until I came upon a longer piece in The Sun about the vigilante attacks on free-speech fighters. It gave the basic details but also featured a few “accounts” by victims of the vigilantes. One in particular caught my interest:

They took us from the cattle pen in groups of five. I remember looking up at the back of the fellow in front of me. It was covered in manure as they had made us lie in a pile of cattle dung while we waited for our turns. The first of the thugs I caught sight of had on a constable’s badge and a white handkerchief tied around his left arm. All of them, it turned out had white handkerchiefs on their arms. Most of our captors had a gun or a rifle in one hand and a club or other such weapon in the other. That is unless they had a bottle of whiskey. This gang of fine men of property and law had all got their courage up by getting good and drunk. All the better to be in high spirits while you’re beating unarmed men, I suppose. Well, they pushed, kicked and prodded us along to a spot where they had us each pay our respects to the flag. The kid in front of me, about 17 years old, got smacked in the head with a wagon spoke and he fell to his knees. Kiss it, you F** Son of a B**, Kiss the G** damn flag, they yelled at him. I could see the blood pouring down his face from a head wound. They had no mercy with him, despite his youth. After he performed their profane ritual, he ran the gauntlet of over a hundred men, each one taking a swing with a club, a bat, or some other weapon. By the end of the line, the kid was crawling through the dirt, leaving a trail of blood behind him.

Next they made Giovanni, “the priest” we used to call him on account of his preaching all the time about non-violence, kiss the flag and sing “The Star Spangled Banner.” Get it right you Dago Son of a B***, one of the bigger thugs yelled before kicking the back of his legs to bring him to his knees. For Giovanni, the worst was not the spit on his face after his song was complete, but the first horrible blow he took from a wagon spoke with a big spike driven through the end. Giovanni had failed to get his arms up in time and it pegged him straight in the forehead. He went down with a thud and didn’t move. He was kicked and poked with more than a few bats and clubs until one of the sharper wits in the pack of wolves got the idea to drag him away and dump his limp body off to the side. I never heard word of Giovanni after that. Lots of fellas went down that way, with no one to remember ’em.

After Giovanni got dragged away, they took big Jacob, or “the Kike” as they called him. They seemed to take a special liking to beating the Jews, Catholics, and Mexicans in our unfortunate little parade. For Jacob, one of the off-duty men of the law selected a hose filled with gravel and tacks. I heard him scream after the first swing and then I was struck from behind by the butt of a pistol and my knees were taken out by a couple swings of a bat. I guess I was a bit too much of a mess for Old Glory ’cause they quickly pushed me past the flag into the gauntlet with no need of a kiss or a song. Just lucky I guess. I couldn’t see well through the blood dripping into my eyes but I stayed low and kept my head covered with my arms as I limped through the gauntlet. There was a whole lot of cursing blending together and stupid yelling about anarchy and godlessness and the lesson I was getting from those pious gentlemen with such brave souls. I remember staggering out the back end of the line and being told that if I ever came back, they’d find a nice spot to bury me on some of their pretty real estate. If I learned a lesson there, though, it was that I was through with non-violence. Poor Giovanni’s corpse was a sterner teacher than his pretty words.

As told by I.W.W. agitator, Buckshot Jack

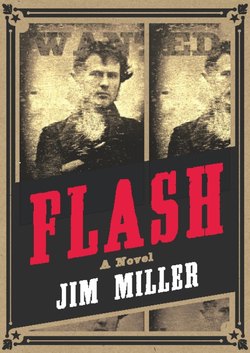

I stopped dead and reread the name, flipped back through the file to the mugshot with the same name. When I asked the librarian who had made the correction and changed the name to Bobby Flash on the back of the picture, he didn’t know. He walked back to check with the main archivist. No luck. The file was put together years ago by a librarian who had passed away. I read the rest of the article that included another account of the gauntlet, but no more on Bobby Flash or his partner, Gus Blanco. Still, this was an interesting piece in the puzzle. I thought for a whimsical moment about my mysterious great grandfather and let myself ponder the possibility that this could be him. No way, I thought, pulling myself back to the task, it was far too interesting a story for my sad family.

I had the librarian copy The Sun article and looked through the rest of the file. No more leads. When the librarian came back to take the file, he recommended I try the Historical Society in Balboa Park. I thanked him and went down to the stacks to find a book on the Magónista revolt of 1911 that I’d been meaning to read. I grabbed it, checked it out, and left the building.

Outside the library it was a beautiful January day, but I hardly noticed that as I walked toward the trolley to meet Ricardo Flores in Tijuana. I was still stuck in my head, thinking about Bobby Flash. Had he been one of the group of Wobblies who were forced to walk back along the railroad tracks toward Los Angeles? Had he been so badly injured that he been taken to a local hospital? There had been nothing in the article beyond the account of the gauntlet. I was still ruminating when I got to the transit center. I absent-mindedly picked up a copy of the LA Times at a news rack and had to run to hop on the trolley to San Ysidro. I found an empty pair of seats by the window and put my satchel with the library book and my notes in it on the seat next to me. I glanced across the aisle at a Mexican woman sitting with her two little boys. They had bags full of souvenirs from the San Diego Zoo.

I looked out the window at a utility box that still had a fading Obama “Hope” poster plastered on it. During the campaign, I had been skeptical about the vagueness of Obama’s messianic appeal, just as I had been brought to tears when he spoke on more than one occasion. It was a battle between my middle-aged pessimism and some deep need for, well, hope. I think more than a few people felt that way. The front page of the Times had a story about things going badly in Afghanistan, one about more lay-offs, another about the latest California budget debacle, and an in-depth piece on rising global instability due to the economic crisis. I couldn’t help but think of the parallels between the beginning of the last century and this one: the economic and political polarization, the anger at “the bosses” as the Wobblies would say. Now though, people weren’t in the streets, at least not yet. People didn’t know who to shoot.

I looked up at a bunch of teenage kids jumping on board in National City. What kind of future would these kids have? It was hard to say. There were dark clouds on the horizon, but sometimes it was times like these that made people stand up. At the next stop, a pair of soldiers got on board in their white uniforms complete with hats. They were talking loudly about sex with prostitutes. I picked up the book on the Magónista revolt and flipped to the middle to look at a black-and-white photo of Ricardo Flores Magón and his brother, Enrique. Both men had thick curly hair and identical handlebar mustaches. Ricardo’s serious expression and little round glasses gave him the aura of a philosopher.

The desert revolution was an international affair, inspired by the Magón brothers who ran the insurgency from their exile in General Otis’s Los Angeles, just after the LA Times building was bombed by a pair of angry AFL labor activists, the McNamera brothers. That bombing led to a wave of anti-labor hysteria in Southern California, thus making the Magónista’s assault on the sparsely populated border region improbable. The fact that both Otis and Spreckels had extensive land, water, and railroad holdings also assured that the odds were against them. Nonetheless, in January 1911 at the I.W.W. headquarters in Holtville, California, a group of mostly Mexican rebels loyal to Magón planned an attack on Mexicali. Soon afterwards, the rebel band captured Mexicali in a predawn raid, killing only the town jailor. Poor sap. The initial success of the raid led to a wave of support from famous voices on the left like Jack London and Emma Goldman, who spoke in San Diego to help rally workers to the cause. The rebels’ biggest backers in the US were the Wobblies and Italian anarchists, both of whose philosophies were in line with Magón’s mix of Kropotkin, Bakunin, and Marx’s. Simply put, Magón called upon the workers to “take immediate possession of the land, the machinery, the means of transportation and the buildings, without waiting for any law to decree it.” Brutally treated by the Diaz dictatorship, and deeply committed to a utopian vision of communal society, Magón’s idealism made him both admirable and seemingly unable to reconcile his dream with political reality. This last malady was something I had a soft spot for. Go figure.

Soon after the success at Mexicali, the rebels took Tecate, where they held off a lackluster attempt by the Mexican army to retake Mexicali. Despite this early success, factional squabbling broke out, and several leadership changes took place in the field. Many of the Mexicans who began the revolt left to fight with Madero, who was also challenging the Diaz regime. This resulted in the odd fact that a majority of the Magónista army was comprised of American Wobblies mixed with a few soldiers of fortune. With Magón permanently ensconced in Los Angeles, sending more anarchist pamphlets than bullets, the leadership ultimately fell to Caryl Rhys Pryce, a Welsh soldier of fortune who had fought in India and South Africa. A surreal pairing, I thought. Pryce fashioned himself a revolutionary and joined the Magónistas after reading a book on the murderous Diaz regime. His biggest victory came when he disobeyed orders from Magón, who wanted him to march east and fight the Mexican army, and instead turned westward to take Tijuana on May 9th, 1911. After a fierce fight, a rebel force of 220 men won a battle in which 32 people died. So the big victory had been an accident of sorts. You had to love it. I turned the page and glanced at a picture of Pryce standing with his hands on his hips, looking like a character in a TV Western. There was a crowd of men at his side, but their faces were indistinguishable. Could one have been Bobby Flash?

I looked at another picture of rebels standing in front of a line of storefronts where someone had replaced the Mexican flag with one reading, “Tierra y Libertad.” It was after this victory that things turned bizarre, and dozens of sightseers from San Diego, who had watched the battle from afar like a football game, flooded the town to loot the shops. With Magón still in Los Angeles, refusing to provide more aid to the untrustworthy Pryce, the rebels turned to revolutionary tourism and gambling to raise funds. It was a kind of Wobbly Vegas. Apparently, San Diegans were fascinated with the rugged revolutionary army, and would pay to take pictures with the wild mix of cowboys, Wobbly hobos, mercenaries, black army deserters, Mexicans, Indians, and random opportunists. I turned the page and stared at a photo of a group of Wobblies, Cocopah Indians, and African-American deserters, still in US uniforms, posing for a shot. No Bobby Flash.

It was during this period that Pryce met Daredevil Dick Ferris. I spotted a picture of Ferris, a pasty, pudgy specimen wearing a hat that made him look like a fading dandy. Today he’d be doing infomercials, I thought. Anyway, Ferris was a booster hired to drum up PR for San Diego and its upcoming Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park. A shameless huckster, Ferris befriended Pryce, brought him to San Diego and sought to persuade him to support Ferris’s notion of a “white man’s republic” in lower Baja, Mexico. When Pryce proved to be of no use (he was arrested on his way back to Mexico and later abandoned the revolution altogether to act in Western movies), Ferris invented an imaginary invading army, going so far as to give a letter to the Mexican consul threatening an attack if Mexico refused to sell Lower Baja, and placing an ad in several newspapers looking for recruits. He even sent a woman on horseback over the border to plant a flag in the name of “suffrage and model government.” With these two stunts under his belt, he then recruited one of the remaining Magónista rebels to the Ferris cause and sent him back across the border to be nearly lynched by angry Wobblies who then elected Jack Mosby, one of their own, as the final commander of the doomed border revolution. I found a photo of Mosby, an unassuming man with a neatly trimmed mustache, wearing a battered fedora, and looking like a librarian with an ammo belt slung across his shoulder.

Led by Mosby, 150 Wobblies and 75 Mexicans took on 560 soldiers of the Mexican army on June 22nd, 1911. Badly outnumbered and low on supplies because of Magón’s refusal to send more, the rebels were routed in three hours, with thirty killed, and the rest fleeing back across the border to be arrested by the United States army. Mosby was shot and killed when he tried to escape military custody. Ferris, shunned by Spreckels, went on the road to enact his version of the farce “The Man from Mexico” on stage. Magón died on the floor of a cell in Leavenworth after having been imprisoned for violating the Espionage Act during the first Red Scare. Bobby Flash? Somehow he made his way back to Holtville to end up on a Wanted poster with Gus Blanco. Then, under another name, he wound up running the gauntlet somewhere in San Diego in 1912. Nothing but traces of a remarkable life. I looked up, and the trolley was heading into San Ysidro. Time for my own trip across the border.

As I walked across the street toward the pedestrian bridge that takes you to the border I noticed the number of gringos headed over was much smaller than the last time I’d been to Tijuana. Almost everyone was Mexican—schoolchildren, maids, janitors, families returning from shopping trips. It seemed the drug wars in the city had scared away large numbers of Americans and forced a good number of Mexicans to do their business in San Diego. The economy probably wasn’t helping either. I wove my way through the labyrinth of concrete, over the footbridge, past the Border Patrol cameras to the big metal turnstile that clanks loudly to announce every living soul leaving or coming home. On the other side, I saw Ricardo, and he met me with a smile and a firm handshake. I started in with my feeble present-tense Spanish, but it quickly became apparent that he spoke perfect English. When I told him that I’d been reading about Ricardo Flores Magón on the trolley, he responded, “No relation, but good choice” with a laugh. We walked by an empty police checkpoint to his car, an old Jeep, parked across the street from the outdoor sports book. I glanced over at a crowd of men drinking Tecates or coffee in styrofoam cups as they stared at the screens monitoring the horse races. We got in the Jeep and drove by a few abandoned curio shops and headed toward the working class section of the city, far from Avenida Revolución, the main tourist strip. The city seemed depressed and tense. I asked Ricardo about the lack of pedestrians coming south.

“Revolución is dead too, man,” he said soberly. “Nothing happening there anymore, even on weekends. The drug wars and the economy in the north are killing the businesses.” The papers had been full of news about murders and big shoot-outs even in broad daylight. Not even the hills where the middle class and the wealthy lived were safe anymore. A newspaper editor had been murdered and others had hired guards. Some police officials had been killed by the drug lords, others were on the take. Tourists had been robbed on the roads south to San Felipe and Ensenada. It was the Wild West. We cruised past a big open-air market full of stalls selling fruit, clothing, small electronic goods, and tacos. I caught a whiff of carne asada coming off a grill. It smelled good and I realized I was hungry. We turned down a street lined with small office fronts and pulled up in front of one with “Justicia” painted on the window.

Inside, I was greeted by a small, pretty woman named Gabriela, who would introduce me to the other women sitting in a circle of small metal chairs, chatting animatedly with each other. The office was small with a big wooden desk that was littered with mail and notebooks. It had a phone but no computer. The women were sitting in a much larger meeting space, a large room with concrete walls and a concrete floor. It would have been ugly if not for the murals someone had painted all over the walls—there were portraits of Zapata, Ché Guevara, Subcommandante Marcos of the Zapatista front, and, interestingly, Ricardo Flores Magón, along with some beautiful nods to Mexican folk art including a calavera with fist upraised. I smiled, sat down on one of the metal chairs, and introduced myself. One of the women thanked me for coming and handed me a plate of pan she had made. I thanked her, took a piece, and listened to their stories.

None of the women spoke English so Ricardo and Gabriela served as translators as, one by one, the women told me about their lives. They lived in the neighborhood under an abandoned maquiladora as the letter Neville had passed on to me had said. Apparently the maquiladora up the hill was owned by a man who had closed down the shop without doing any cleanup, so the chemicals involved in making batteries were left under a big canvas tent. Once the tons of abandoned waste from the batteries began to seep into the earth, it entered the well that supplied the barrio down the hill. Worse still, when the rains came in the winter, the chemicals would get washed down the hill, through the dirt streets where their children played. One of the women, Marisol, a stout, kind-faced grandmother with lively eyes, had come with pictures of the waste heap, the neighborhood from above, and children playing soccer, kicking the ball through puddles of toxic waste. I surveyed the pictures and studied Marisol’s face as she explained how it had begun with people getting sick to their stomachs or having their eyes burn for no apparent reason. Then there were strange cases of cancer, lots of them. And finally, mothers started giving birth to babies with terrible birth defects, babies with damaged brains or horrible disfigurements. By then, I was taking notes furiously, as one woman after another added her tale of betrayal.

I was particularly struck by the fact that these women still worked at other factories, for ten or twelve hours a day, and then came home to take care of their families. They woke before dawn, worked at home, at the factory, and at home again, and still found time to organize Las Madres Unidas against all odds. It was jaw-dropping. Another madre, Rosa, a sharp-eyed, middle-aged woman with obvious scars on her wiry arms and her fierce heart, angrily told me how the owner of the company had shut it down overnight, taken out the valuable equipment, and shipped it to China, where he had moved the operation because the labor was even cheaper there. NAFTA and Mexican law forbid such practices, but there were no enforcement clauses. The Mexican government ignored its own labor laws to appease the companies, and the United States ignored the matter altogether. All the while, the owner sat in a big house just across the border without a care in the world, fat and happy, as Rosa put it.

Finally, Isabel, a short, Indian-looking woman in her thirties, wearing a striking, hand-embroidered blouse and blue jeans told me about how the closing of the plant had changed the life of the barrio. Most of the people in the neighborhood had moved there to work for the factory on the hill. They came, built their own houses out of what they could—with no infrastructure, no water, no help from the government or the company. When the company left, they all had to get jobs elsewhere, further away, so the walk took an hour each way. The women had no protection on their walks and some had disappeared like the women in Juarez. They could not trust the police, and the other factory owners would not provide transportation and punished them if they arrived late or left early. It was a house of pain, I thought to myself as I looked into the faces of these women, faces lined with worry, work, and suffering. Still there was fight in them—hope against all odds. I promised them that I would tell their tale and come back to see their neighborhood with a photographer. Then I thanked them for their stories and shook each of their hands like a prayer for more power than I had to redress their great wrongs.

It was dark outside as Ricardo drove me back to the border. He thanked me for coming and I told him it was my pleasure to do what I could to tell this story. We made plans for my return visit to tour the neighborhood. The lights in the hills twinkled a reddish-yellow and car horns blared angrily in the rush hour traffic. He let me off at the end of a long line to get back. “Goodbye, my friend,” he said before driving off into the night. I dropped a coin in a basket at the feet of an ancient Indian woman, who was begging on a dirty wool blanket by the line. Some little girls sold me a pack of gum and I looked over at a line of shops hawking cheap liquor and pharmaceuticals for those returning to the land of the free. In line, I closed my eyes and listened to the distant strains of music from the Mexican street blending with hundreds of car radios talking in Spanish and English. AC/DC and Los Tigres del Norte. At the end of the line, the guards regarded me suspiciously as they always seemed to do. They sternly pulled aside the whole family behind me and took them to secondary inspection as I headed to the trolley. On the way back, the train was half empty and I closed my eyes and tried to fall asleep with visions of Las Madres Unidas dancing in my head.