Читать книгу When Marnie Was There - Joan G. Robinson - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter Four

THE OLD HOUSE

ANNA THOUGHT OF the house as soon as she awoke next morning. In fact she must have been thinking about it even before she awoke, because by the time she opened her eyes and saw the white, sloping ceiling of her little room, and smelt the old, sweet, warm smell of the cottage, she was saying to herself – still half asleep – “I must hurry It’s waiting for me.” Then she realised where she was.

Thank goodness the journey to Norfolk was over! She must have been dreading it more than she had realised. It had been an unknown adventure looming up ahead, and all her life at home during the past few weeks had been a preparation for it. Now it was over. She was here. And as soon as she could she would go down to the creek again and see the house.

At breakfast Mrs Pegg said, “How about coming into Barnham with me on the bus? I usually goes once a week to the shops, and it would make something for you, wouldn’t it, lass?”

Anna looked doubtful.

“Or maybe you’d like to play with young Sandra-up-at-the-Corner?” Mrs Pegg suggested. “She’s a well behaved, nicely-spoken little lass. I know her mum and I could take you up there.”

Anna looked more doubtful still.

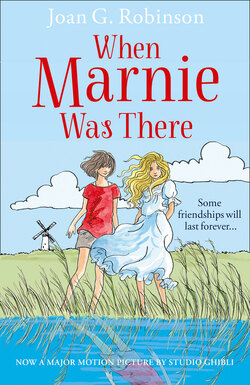

Had she noticed the windmill yesterday, Sam asked. It was a fair way off, and not much to look at when you got there, but that might make something too.

Mrs Pegg rounded on him. That would do nothing of the sort, she said. It was too far for the lass on her own and all along the main road into the bargain.

“Oh, ah, so it is!” said Sam. “Never mind, my biddy. Maybe I’ll take you there myself one day.”

Anna said she did not mind at all, she was quite all right doing nothing. “Really I like doing nothing better than anything else,” she explained earnestly. They both laughed at this, but Anna, determined to be taken seriously, stared hard at the tablecloth, looking as ordinary as she knew how.

“I don’t know that I can do with you sitting around in the kitchen all day, my duck,” Mrs Pegg said doubtfully. “What with the cleaning and the cooking and the washing and Sam being under my feet half the time as it is—”

Anna interrupted. “Oh, no! I meant outside. Can I go down to the creek?”

Mrs Pegg looked relieved. She had been afraid Anna might have wanted to spend the day in the front room, the door of which was always kept closed except on special occasions. Yes, of course Anna could go down to the creek. Or if the tide was out she could walk over the marsh to the beach, and if it was high she could always go down in Wuntermenny’s boat. “As long as you don’t mind not having no company,” she said. Anna assured her she did not mind.

“And just as well, if you go down in the boat with Wuntermenny West,” said Sam. “He can’t abide having to talk.” He stirred his tea ponderously with the handle of his fork and looked hopefully across the table at her. “No doubt you’re thinking that’s a queer name, eh?” he said, smiling.

Anna had not thought about it but said, “Yes,” politely.

“Ah! I’ll tell you how it was, then, since you’re asking,” said Sam. “Wuntermenny’s ma – old Mrs West, that was – she had ten already when he was born. ‘What’re you going to call him, mam?’ they all says, and she says, tired-like, ‘Lord knows! He’m one-too-many and that’s a fact.’ So that’s how it was!” he said, laughing and spluttering into his mug of tea. “And Wuntermenny West he’s been ever since.”

As soon as she could get away, Anna ran down to the staithe. The tide was out and the creek had dwindled to a mere stream. At first she was disappointed when she saw the old house again. It seemed to have lost some of its magic, now that it only looked out on to a littered foreshore instead of a wide stretch of water. But even as she looked, she saw that it was still the same quiet, friendly-faced house. She felt rather as if she had come to visit an old friend, and found that friend asleep.

She scrambled up the bank, clinging on to tufts of grass, and walked slowly along the footpath in front of the house, looking sideways into the windows. She was not sure if she was trespassing, and it was difficult to see clearly without stopping and pressing her face up close against the glass. Suppose someone should be watching, from inside! More than ever now she had the feeling she was spying on someone who was asleep. She moved nearer and saw only her own face staring back at her, pale and wide-eyed.

The Peggs were right, she thought. No-one was living in the house. Nevertheless, it still had a faintly lived-in look, more as if it were waiting for its people to return, than having been deserted. She grew bolder and looked through the narrow side windows on either side of the front door. There was a lamp on a windowsill, and a torn shrimping net was leaning up against the wall. She saw that a wide central staircase went up from the middle of the hall.

That was all there was to see. She slid down the bank again, waded across the creek, and sat for a long time with her chin in her hands, staring across at the house, and thinking about nothing. If Mrs Preston had known she would have been even more worried than she had been, but at the moment she was more than a hundred miles away, pushing a wire trolley round the supermarket. She had forgotten that in a place like Little Overton you can think about nothing all day long without anyone noticing.

Anna did go down to the beach in Wuntermenny’s boat. She found him as unsociable as the Peggs had promised. He was small and bent, with a thin, lined face, and eyes which seemed to be permanently screwed up against the light, looking into the far distance. After the first grunt of recognition he hardly noticed her, so she was able to sit up in the bow of the boat, looking ahead, and ignore him too. This suited her well, but it made her feel lonelier, and she was a little frightened that first afternoon. There seemed such a huge expanse of water and sky, and so little of herself.

Sitting alone on the shore, while Wuntermenny in the far distance was digging for bait, she looked back at the long, low line of the village and tried to pick out The Marsh House. But it was not there! She could see the boathouse, and the white cottage at the corner, and farther away still she could see the windmill. But along where The Marsh House should have been there was only a bluish-grey smudge of trees.

Alarmed, she stood up. It had to be there. If it was not, then nothing seemed safe any more… nothing made sense… She blinked, opened her eyes wider, and looked again. Still it was not there. She sat down then – with the most ordinary face in the world, to show she was quite independent and not frightened at all – and with her knees up to her chin, and her arms round her knees, made herself into as small and tight a parcel as she could, until Wuntermenny came trudging up the beach with his fork and his bucket of bait.

“Cold?” he grunted, when he saw her.

“No.”

She followed him down to the boat, and those were the only two words that passed between them all the afternoon. But as they rounded a bend in the creek and she saw the old house gradually emerge from its dark background of trees, she felt so hot and happy with relief that she nearly said, “There it is!” out loud. She realised now that it had been there all the time. In the distance the old brick and blue-painted woodwork had merely merged into the blue-green of the thick garden trees. She realised something else, too. As they passed close under the windows, on the high tide, she saw that the house was no longer asleep. Again it had a watching, waiting look, and again she had the feeling it had recognised her and was glad she was coming back.

“Enjoy yourself?” asked Mrs Pegg, who was frying sausages and onions in the scullery when Anna returned.

Anna nodded.

“That’s right, my duck. You do what you like. Just suit yourself and follow your fancy.”

“And maybe I’ll take you along to the windmill one day if you’re a good lass,” said Sam.