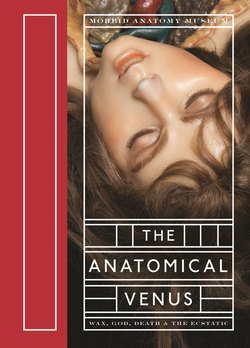

Читать книгу The Anatomical Venus - Joanna Ebenstein - Страница 44

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление(48) preVious Elegantly posed écorchés showing the female reproductive system, by Jacques-Fabien Gautier d’Agoty. Taken from Anatomie des parties de la génération de l’homme et de la femme (1773) (left page, both; right page, right side) and Anatomie generale des visceres en situation (1772) (right page, left side). Vesalius, unlike many contemporary anatomists, conducted his own dissections of cadavers, which led him to recognize a variety of mistakes in the work of Claudius Galen (c. 129–216 Ce), on whose Hippocratic Corpus, an anthology of texts about the body from the fourth and fifth centuries bCe, much anatomical knowledge of the time relied. The errors, Vesalius discovered, stemmed from the fact that the old master performed most of his dissections on animals (especially pigs, dogs, and apes) rather than humans, due to prohibitions about human dissection in Roman law. His inaccuracies had been handed down for generations due, in part, to the way in which dissections were conducted, with the professor standing above the proceedings and reading aloud from Galen, while a labourer conducted the dirty work of dissection. Vesalius understood the power of illustration; his woodcuts, he explained, were not ‘executed merely as simple outlines, like ordinary diagrams in text books, but have been given a particular pictorial quality’. De Humani Corporis fig. 26 figs 26, 27 Dissectible, pregnant anatomical figure and removable pieces, carved to scale from linden wood (c. 1700). Fabrica was read by unprecedented numbers of people, due to new printing technology that enabled the mass production of high-quality, large-scale illustrations. In Fabrica’s wake, dozens of artistic and expressive anatomical atlases—many of them large, luxurious affairs, of interest to private collectors as much as students of anatomy—were produced. Some of the most memorable are the work of French artist and anatomist Jacques-Fabien Gautier d’Agoty (1710–85); he was among the first to create an atlas in full colour, by a mezzotint process of his own devising. His images have a dreamy, painterly quality; indeed, he sometimes even varnished his colour prints in imitation of oil paintings. They contrast with the annotated diagrammatic illustrations by Henry Carter (1831–97) that appeared in Gray’s Anatomy, which was published in England in 1858. Avoiding the inclusion of any extraneous detail, Carter’s style was designed for optimum clarity in pressurized clinical contexts and epito mizes the modern scientific method. The modellers who created the anatomical wax models at La Specola and other wax workshops depended for the veracity of their work on the anatomi cal illustrations featured in anatomical atlases. Firstly, the modeller, usually taking advice from an anatomist or natural philosopher, would select an illus tration, or illustrations, from trusted anatomical atlases by Vesalius, Albinus, AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 48 12/01/2016 12:14 chapter one[1]