Читать книгу The Anatomical Venus - Joanna Ebenstein - Страница 65

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

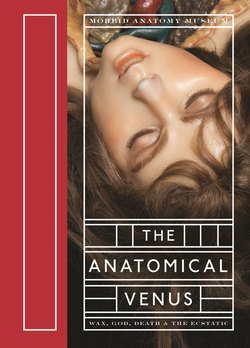

Оглавление(70) hile Susini’s expert artistry is responsible for the convincing appearance of La Specola’s Medici Venus, she owes much of her unnerving presence to the wax with which she is made. Wax can look uncannily like flesh; it has a similarly moist appearance, depth of colour (due to the even suspension of added pigments), and transparent opacity. It has also been intimately related to death rituals, where it represents the stillness of a corpse that appears only to need its spirit to be immediately reanimated. Wax is, by nature, contradictory: solid and molten, stable and ephemeral, ‘flesh’ and yet simulacrum, seemingly alive, yet merely material. Because of these qualities, wax has been the medium of choice for the making of human surrogates for anatomical, popular, religious, and magical preVious Effigy of Teresa Urrea (1873–1906), or Santa Teresita, Mexican folk healer and revolutionary. Her gift for miraculous healings was acquired after emerging from weeks spent in a trance. She lies in a golden casket at Carmen Alto, Oaxaca, Mexico, founded in 1696. fig. 28 fig. 29 fig. 30 fig. 28 Small wooden coffin containing a beeswax poppet—with a slot in its back, into which written spells, nail parings,or hair, can be inserted—that once belonged to a clairvoyant known as Madam de la Cour. fig. 29 This Agnus Dei—a wax amulet, imprinted with the lamb of God and blessed by the pope—was found in Oxfordshire, England, and dates from 1578, when it was a criminal offence to be Catholic. purposes. Wax figurines in the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead (c. 1550–50 bCe) are described as engraved with the names of Ramesses III’s enemies and bound with string. Voudou dolls and poppets, proxy bodies meant to inflict harm or death to enemies, have been used since at least the medieval period. Wax was also an essential part of the mummification process. The portraits that decorate the mummy casings at Fayum, Egypt, were painted in a combination of wax and pigment known as encaustic. They were displayed in the home during the life of the subject, and, upon death, attached to the mummy case in which their owner would spend eternity. In Ancient Rome, wax was used to create death masks and funerary effigies of notable personages, presaging the wax museums. The symbolic and ritual significance of wax has been particularly rich in Christian, especially Catholic, tradition. Wax is seen as fragile, transitory, and malleable: like man, moulded by God and lit by his spirit. Bees are ascribed exemplary virtues in Christian iconography, and liturgical candles are tradi tionally made of beeswax. In Italy, the plague of 1575–77, which decimated the population, also caused the rapid expansion of the wax industry and greatly AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 70 12/01/2016 12:14 chapter two[2]