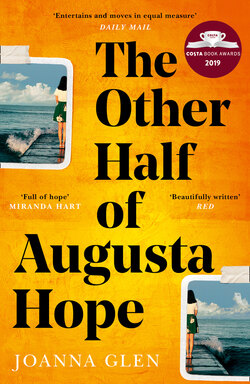

Читать книгу The Other Half of Augusta Hope - Joanna Glen - Страница 15

Augusta

ОглавлениеThe train passed and the crossing gates came up – and Barbara Cook marched back through the door, her face set, her skirt done up, and she said that she was resigning. My mother said that of course she wasn’t, and they’d all agreed that Graham Cook was most welcome at the Craft Fair, and they went on having their committee meeting as if nothing at all had happened.

This time, I’d asked to be in charge of second-hand books. Amongst the tatty Enid Blyton paperbacks, I found an old leather book of Victorian children’s poems and rhymes, published in 1900, illustrated with beautiful watercolour plates, and I took this without asking my mother, and I put it under my mattress without telling anyone, even Julia.

I knew deep down that this was stealing.

But I wanted this book so badly.

Inside it were all the normal nursery rhymes that Julia and I knew off by heart and used to say so fast that the words blurred into each other when we were younger. ‘Humpty Dumpty’, ‘Little Bo Peep’, and ‘Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary’, which was another of my mother’s nicknames for me and drove me absolutely mad.

My favourite poem was called ‘The Pedlar’s Caravan’ by William Brighty Rands. The illustration showed trees and birds and caterpillars – and a Victorian caravan, made of wooden slats, yellow and red, with flowers painted in vertical plaited lines to the right and left at the front, and butterflies fluttering above them. It had tiny windows with geraniums in boxes, and ladder steps, and wooden wheels with cream-coloured spokes, and a smoking tin chimney, and it was passing under a huge tree, with a dark-looking woman and child at the window, and the pedlar man leading a dapple-grey horse to a dusky not quite see-able horizon.

When I was alone, I read it and I read it, and it made my heart beat and my soul soar, and I heard the noise of singing coming from deep down inside me, where he comes from nobody knows, and I was in the caravan, or where he goes to, but on he goes, and I was leading the dapple-grey horse, and my horizon was unknowable, and every time I climbed the ladder, I gave my own life story a different ending. And I never once ended up in Hedley Green.

Perhaps the reason I didn’t show Julia the book was that I couldn’t bear to admit to her that I wanted to leave.

Go anywhere but where I was.

The minute I could.

Of course, I knew that she would want to stay.

And, if I left and she stayed, we wouldn’t be Justa any more.

We’d be ripped apart like the ragdoll, with our stuffing falling out.