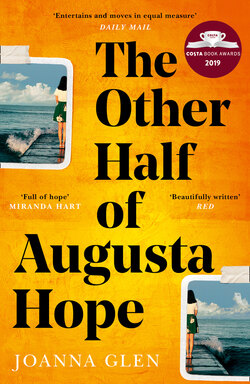

Читать книгу The Other Half of Augusta Hope - Joanna Glen - Страница 24

Parfait

ОглавлениеI told Víctor I was planning to be a teacher or a doctor, an artist or a poet once I made it to Spain.

‘Well let’s start with the art,’ he said. ‘I can help you with the art.’

He went and got an old easel and a case of mucky paints and sketching pencils from a store cupboard out at the back of his little house.

I started off copying great Spanish artists from his History of Art book in pencil. We moved on to pastel. Then we tried some paint.

Looking through Víctor’s book about living European artists, I found an artist called Sami Terre who had skin the same colour as mine and wore his black hair in lots of long plaits. He’d been born in what he called a shithole on the outskirts of Brussels and started out making graffiti.

‘Can you make my hair like this?’ I asked Gloria and Douce, pointing to his photograph.

‘Who are you getting yourself so handsome for?’ said Gloria.

I shook my head.

They got to work on my hair, with Amie Santiana who lived on the homestead next to us and knew all about hairdressing.

As I walked out of the hut the next day, I found I was standing a little taller. Because, if Sami Terre was raised in a shithole but went on to be famous and written about in books, it could happen to anyone. It could even happen to me.

The African mourning doves were calling in the acacia tree opposite the hut – krrrrrrr, oo-OO-oo – as I took the photograph of my parents’ wedding out of the Memory Box. In it I found the little card my father had given my mother on their wedding night.

‘God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,’ it said. ‘The courage to change the things I can. And the wisdom to know the difference.’

It made my mind up.

This was something I could change.

The place we lived.

I did have the courage, I knew I did.

I began to paint a portrait of my parents, falling into each other on their wedding day, my father in a dark suit and my mother in the shiny wedding dress lent to her by the Baptists.

‘Tell me I’m right to go,’ I said to my father’s photograph, but it didn’t answer.

I worked at the painting hour after hour, covering it with an old mat, telling everyone they mustn’t look at it, not yet.

Even when my arms ached from banana-picking, I still painted.

Then it was finished.

Víctor came down on his bike, and the rest of them gathered around, and, feeling suddenly shy, I took off the mat to reveal the painting.

‘You’re a genius,’ said Víctor. ‘A total natural! Stay here and you’ll become a famous Burundian artist.’

The rest of them stared at our mother and father, perhaps hoping that they might walk off the page and come and live with us in the hut again.

‘This is how we’ll earn money as we go,’ I said to them all. ‘By painting portraits.’

‘I’m not coming,’ said Pierre. ‘I’m going to stay here and fight.’

‘Fight?’ I said. ‘Fight as in struggle?’

‘Fight as in anything it takes,’ said Pierre.

My father’s twinkly eyes and his cheek, his turning-the-other-cheek, stared out at us from the easel and stopped twinkling for a second.

‘What would Pa say?’ I said.

‘And what good did it do him? Refusing to retaliate? Breaking the chain?’ said Pierre.

Wilfred sat staring.

The girls looked sad.

Víctor said nothing.

‘When are we leaving?’ said Zion.

Then, one by one, we all walked quietly away from the easel where my mother and father stayed laughing love into each other’s eyes.

‘Patience, Little Bro,’ I said, and I tried to cheer myself up by dancing about with him, the way I imagined flamenco dancers might dance, though, looking back, it was some other way altogether.

‘Come and join in!’ I said to the girls. ‘You sway your hips like this, and you lift your arms and twist around – and the girls wear bright-coloured dresses like butterflies.’

‘You can shout out Olé whenever you feel like it!’ said Zion.

But Gloria said, ‘You dance, boys. I like watching.’

Douce nodded.

Whenever Zion and I found ourselves alone together, we’d say Olé and do our special up-down high-five as a way of believing in the journey we would make.

‘Olé Olé Olé Olé.’