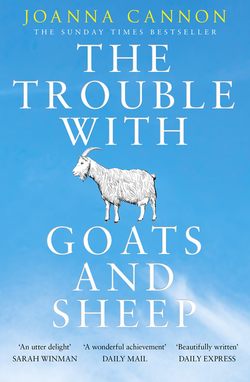

Читать книгу The Trouble with Goats and Sheep - Joanna Cannon, Joanna Cannon - Страница 12

21 December 1967

ОглавлениеSirens hammer into the road, drawing the avenue from its sleep. Lights fizz and tick, and aquariums of people look out into the night. Dorothy watches from the landing. The banister digs into her bones as she leans forward, but this is the window with the best view, and she leans a little more. As she does, the bells of the siren stop and the fire engine empties men on to the street. She tries to listen, but the glass dulls their voices, and the only sound she hears is air moving through her throat, and the stamp of a pulse in her neck.

Ferns of ice grow at the corners of the windows, and she has to peer around them to see properly. There are hoses twisting across pavements, and rivers of light shining into the black. It feels unreal, theatrical, as though someone is staging a play in the middle of the avenue. Across the road, Eric Lamb opens his front door, pulling on a jacket, shouting back before he runs on to the street, and all around her, windows catch and push, spilling breath into the darkness.

She calls to Harold. She has to call several times, because his dreams are like cement. When he does appear, he has the frayed edges of someone who has been shocked into consciousness. He wants to know what’s going on, and he shouts the question at her, even though he is standing three feet away. She can see the skin of sleep in the corners of his eyes, and the journey of the pillow across his cheek.

She turns back to the window. More doors have opened, more people have appeared. Above the smell of the house, above the polished windowsills and the Fairy Liquid sink, she imagines she can sense the smoke, sliding in through the cracks and the splinters, and finding its way through the bricks.

She looks back at Harold.

‘I think something very bad has happened,’ she says.

*

They reach the garden. John Creasy calls across the avenue, but his voice is lost in the churn of the engine and the punch of boots on the concrete. Dorothy peers through the dark towards the bottom of the road. Sheila Dakin is standing on the lawn, feeding her hands into her face, the wind whipping at her dressing gown, smacking the material against her legs like a flag. Harold tells Dorothy to stay where she is, but it feels as though the fire has a magnetic field, and everyone is pulled closer, drawn along paths and pavements. The only one who is still is May Roper. She stands in her doorway, held there by the light and the noise and the smell. Brian catches her as he rushes past, but she barely seems to notice.

The firemen work like machinery, forming links of a chain which drags water from the earth. There is an arc of sound. An explosion. Harold is shouting to Dorothy to get back inside, but she moves a little closer instead. She watches Harold. He is too interested in what’s happening to notice, and she edges her way next to the wall. She just needs to see for a moment. To find out if it’s really happened.

She reaches the far end of the garden, when a fireman begins sweeping the air with his arms, forcing them back like puppets, and they collect in the middle of the avenue, knotted together against the frost.

The fireman is shouting questions. How many people live in the house?

They all answer at once, and their voices are smeared, taken by the wind.

The fireman scans their faces and points at Derek. ‘How many?’ he says again, his mouth shaping around the words.

‘One,’ he shouts, ‘just one.’ Derek looks back at his own house, and Dorothy follows his gaze. Sylvia stands at the window, Grace in her arms. Sylvia watches them, then turns away, holding the child’s head against her skin. ‘His mother lives in a nursing home, but he’s taken her away for Christmas,’ Derek says. ‘So it’s empty.’ The fireman is already running back and Derek’s words are wasted to the darkness.

A roll of smoke unfolds towards the sky. It loses itself against the black, whispering edges caught against a bank of stars before it feathers into nothing. Harold finds Eric’s eyes, and Eric shakes his head, a brief movement, almost nothing. Dorothy catches it, but looks away, back to the grip of the noise and the smoke.

None of them notice him, not to begin with. They are too captured by the flames, watching the darts of orange and red that fasten and catch in the windows. It’s Dorothy who sees him first. Her shock is soundless, static, but still it finds each of them. It stumbles around the group, until they all turn from number eleven and stare.

Walter Bishop.

The wind slips inside his coat and lifts the collar. It takes spirals of his hair and tries to cover his eyes. His lips are moving, but the words aren’t yet ready to leave. There is a carrier bag. It falls from his hand and a tin skittles across the pavement and into the gutter. Dorothy lifts it back and tries to return it to him.

‘Everyone thought you’d gone away with your mother,’ she says, but Walter doesn’t hear.

There are shouts from the house, carried across the avenue, and one fireman’s voice lifts above the rest.

There’s someone in there, it says. There’s someone in the house.

They all turn from the fire to look at Walter.

‘Who’s inside?’ It’s the question in everyone’s eyes, but it’s Harold who gives it a voice.

At first, Dorothy doesn’t think Walter has even heard the question. His gaze doesn’t move from the slurry of black smoke, which has begun to pour from the windows of his house. When he finally replies, his voice is so soft, so whispered, they all have to lean forward to listen.

‘Chicken soup,’ he says.

Harold frowns. Dorothy can see all the wrinkles of the future pinch together on his forehead.

‘Chicken soup?’ The wrinkles become even deeper.

‘Oh yes.’ Walter’s eyes don’t move from number eleven. ‘It works wonders for the flu. Terrible thing, isn’t it, the flu?’

They all nod, like ghostly marionettes in the darkness.

‘We’d only just got to the hotel when she took ill. I said to her, Mother, I said, when you’re under the weather, what you need is your own bed. And so we turned around and came home again.’

And all the marionette eyes stare at Walter’s first-floor window.

‘And she’s up there now?’ says Harold, ‘your mother?’

Walter nods. ‘I couldn’t take her back to the nursing home, could I? Not in that state. So I put her to bed and went to ring for the doctor.’ He looks at the tin Dorothy handed back to him. ‘I wanted to explain to him I was giving her the soup, as he advised. They put so many additives in these things now. You can’t be too careful, can you?’

‘No,’ says Dorothy, ‘you can’t be too careful.’

The smoke creeps across the avenue. Dorothy can taste it in her mouth. It blends with the fear and the frost, and she pulls her cardigan a little closer to her chest.

*

Harold walks into the kitchen through the back door. Dorothy knows he has something to tell her, because he never uses the back door unless it’s an emergency or he is wearing his wellington boots.

She looks up from her crossword and waits.

He moves around the work surfaces, lifting things up unnecessarily, opening cupboard doors, looking at the bottom of crockery, until he can’t hold on to the words any longer.

‘It’s awful in there,’ he says, as he replaces a mug on the mug tree. ‘Awful.’

‘You’ve been inside?’ Dorothy puts down her pen. ‘Are you allowed to go inside?’

‘The police and the fire service haven’t been there for days. No one said we couldn’t go inside.’

‘Is it safe?’

‘We didn’t go upstairs.’ He finds a packet of bourbons she had deliberately hidden behind the self-raising flour. ‘Eric didn’t think it was respectful, you know, under the circumstances.’

Dorothy doesn’t think it’s respectful rummaging around in the downstairs either, but it’s easier to say nothing. If you challenge Harold, he spends days justifying himself, like turning on a tap. She had wanted to go in there herself. She even got as far as the back door, but she’d changed her mind. It probably wouldn’t be wise, under the circumstances. Harold, however, had the self-discipline of a small toddler.

‘And the downstairs?’ she says.

‘That’s the strangest thing.’ He takes the top off a bourbon and makes a start on the buttercream. ‘The lounge and the hallway are a mess. Completely gone. But the kitchen is almost untouched. Just a few smoke marks on the walls.’

‘Nothing?’

‘Not a thing,’ he says. ‘Clock ticking away, tea towel folded on the draining board. Ruddy miracle.’

‘Not a miracle for his mother, God rest her soul.’ Dorothy reaches for the tissue in her sleeve, then thinks better of it. ‘Not a miracle they came back early.’

‘No.’ Harold looks at the next biscuit, but puts it back in the packet. ‘Although she wouldn’t have known a thing. The flu had made her delirious, apparently. Couldn’t even get out of bed. That’s why he’d gone to ring for the doctor.’

‘I don’t understand why he didn’t take her back to the nursing home.’

‘What? In the middle of the night?’

‘It might have saved her life.’

Dorothy looks past Harold and the curtains, and out on to the avenue. Since the fire, it had slipped into a quiet, battleship grey. Even leftover Christmas decorations couldn’t lift it. They seemed dishonest, somehow. As though they were trying too hard to jolly everyone along, to pull their eyes from the charred shell of number eleven.

‘Stop over-analysing things. You know too much thinking makes you confused,’ Harold says, watching her. ‘It was a discarded cigarette, or a spark from the fire. That’s what they’ve settled on.’

‘But after what was said? After what we all decided?’

‘A discarded cigarette.’ He took the biscuit and broke it in half. ‘A spark from the fire.’

‘Do you really believe that?’

‘Loose lips sink ships.’

‘For goodness sake, we’re not fighting a war, Harold.’

He turns and looks through the window. ‘Aren’t we?’ he says.