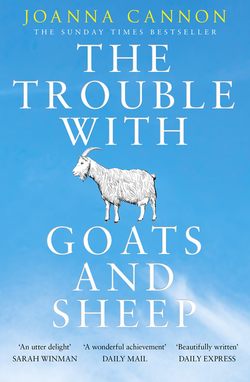

Читать книгу The Trouble with Goats and Sheep - Joanna Cannon, Joanna Cannon - Страница 8

Number Four, The Avenue 21 June 1976

ОглавлениеMrs Creasy disappeared on a Monday.

I know it was a Monday, because it was the day the dustbin men came, and the avenue was filled with a smell of scraped plates.

‘What’s he up to?’ My father nodded at the lace in the kitchen window. Mr Creasy was wandering the pavement in his shirtsleeves. Every few minutes, he stopped wandering and stood quite still, peering around his Hillman Hunter and leaning into the air as though he were listening.

‘He’s lost his wife.’ I took another slice of toast, because everyone was distracted. ‘Although she’s probably just finally buggered off.’

‘Grace Elizabeth!’ My mother turned from the stove so quickly, flecks of porridge turned with her and escaped on to the floor.

‘I’m only quoting Mr Forbes,’ I said, ‘Margaret Creasy never came home last night. Perhaps she’s finally buggered off.’

We all watched Mr Creasy. He stared into people’s gardens, as though Mrs Creasy might be camping out in someone else’s herbaceous border.

My father lost interest and spoke into his newspaper. ‘Do you listen in on all our neighbours?’ he said.

‘Mr Forbes was in his garden, talking to his wife. My window was open. It was accidental listening, which is allowed.’ I spoke to my father, but addressed Harold Wilson and his pipe, who stared back at me from the front page.

‘He won’t find a woman wandering up and down the avenue,’ my father said, ‘although he might have more luck if he tried at number twelve.’

I watched my mother’s face argue with a smile. They assumed I didn’t understand the conversation, and it was much easier to let them think it. My mother said I was at an awkward age. I didn’t feel especially awkward, so I presumed she meant that it was awkward for them.

‘Perhaps she’s been abducted,’ I said. ‘Perhaps it’s not safe for me to go to school today.’

‘It’s perfectly safe,’ my mother said, ‘nothing will happen to you. I won’t allow it.’

‘How can someone just disappear?’ I watched Mr Creasy, who was marching up and down the pavement. He had heavy shoulders and stared at his shoes as he walked.

‘Sometimes people need their own space,’ my mother spoke to the stove, ‘they get confused.’

‘Margaret Creasy was confused all right.’ My father turned to the sports section and snapped at the pages until they were straight. ‘She asked far too many questions. You couldn’t get away for her rabbiting on.’

‘She was just interested in people, Derek. You can feel lonely, even if you’re married. And they had no children.’

My mother looked over at me as though she were considering whether the last bit made any difference at all, and then she spooned porridge into a large bowl that had purple hearts all around the rim.

‘Why are you talking about Mrs Creasy in the past tense?’ I said. ‘Is she dead?’

‘No, of course not.’ My mother put the bowl on the floor. ‘Remington,’ she shouted, ‘Mummy’s made your breakfast.’

Remington padded into the kitchen. He used to be a Labrador, but he’d become so fat, it was difficult to tell.

‘She’ll turn up,’ said my father.

He’d said the same thing about next door’s cat. It disappeared years ago, and no one has seen it since.

*

Tilly was waiting by the front gate, in a jumper which had been hand-washed and stretched to her knees. She’d taken the bobbles out of her hair, but it stayed in exactly the same position as if they were still there.

‘The lady from number eight has been murdered,’ I said.

We walked in silence down the avenue, until we reached the main road. We were side by side, although Tilly had to take more steps to keep up.

‘Who lives at number eight?’ she said, as we waited for the traffic.

‘Mrs Creasy.’

I whispered, in case Mr Creasy had extended his search.

‘I liked Mrs Creasy. She was teaching me to knit. We did like her, Grace, didn’t we?’

‘Oh yes,’ I said, ‘very much.’

We crossed the road opposite the alley next to Woolworth’s. It wasn’t yet nine o’clock, but the pavements were dusty hot, and I could feel material stick to the bones in my back. People drove their cars with the windows down, and fragments of music littered the street. When Tilly stopped to change her school bag to the other shoulder, I stared into the shop window. It was filled with stainless-steel pans.

‘Who murdered her?’ A hundred Tillys spoke to me from the display.

‘No one knows.’

‘Where were the police?’

I watched Tilly speak through the saucepans. ‘I expect they’ll be along later,’ I said, ‘they’re probably very busy.’

We climbed the cobbles in sandals which flapped on the stones and made us sound like an army of feet. In winter ice, we clung to the rail and to each other, but now the alley stretched before us, a riverbed of crisp packets and thirsty weeds, and floury soil which dirtied our toes.

‘Why are you wearing a jumper?’ I said.

Tilly always wore a jumper. Even in scorched heat, she would pull it over her fists and make gloves from the sleeves. Her face was magnolia, like the walls in our living room, and sweat had pulled slippery, brown curls on to her forehead.

‘My mother says I can’t afford to catch anything.’

‘When is she going to stop worrying?’ It made me angry, and I didn’t know why, which made me even angrier, and my sandals became very loud.

‘I doubt she ever will,’ said Tilly, ‘I think it’s because there’s only one of her. She has to do twice the worrying, to keep up with everyone else.’

‘It’s not going to happen again.’ I stopped and lifted the bag from her shoulder. ‘You can take your jumper off. It’s safe now.’

She stared at me. It was difficult to see Tilly’s thoughts. Her eyes hid behind thick, dark-rimmed glasses and the rest of her gave very little away.

‘Okay,’ she said, and took off her glasses. She pulled the jumper over her head, and when she appeared on the other side of the wool, her face was red and blotchy. She handed me the jumper, and I turned it the right way, like my mother did, and folded it over my arm.

‘See,’ I said, ‘it’s perfectly safe. Nothing will happen to you. I won’t allow it.’

The jumper smelt of linctus and unfamiliar soap. I carried it all the way to school, where we dissolved into a spill of other children.

*

I have known Tilly Albert for a fifth of my life.

She arrived two summers ago in the back of a large, white van, and they unloaded her along with a sideboard and three easy chairs. I watched from Mrs Morton’s kitchen, whilst I ate a cheese scone and listened to a weather forecast for the Norfolk Broads. We didn’t live on the Norfolk Broads, but Mrs Morton had been there on holiday, and she liked to keep in touch.

Mrs Morton was sitting with me.

Will you just sit with Grace while I have a little lie-down, my mother would say, although Mrs Morton didn’t sit very much at all, she dusted and baked and looked through windows instead. My mother spent most of 1974 having a little lie-down, and so I sat with Mrs Morton quite a lot.

I stared at the white van. ‘Who’s that then?’ I said, through a mouthful of scone.

Mrs Morton pressed on the lace curtain, which hung halfway down the window on a piece of wire. It dipped in the middle, exhausted from all the pressing. ‘That’ll be the new lot,’ she said.

‘Who are the new lot?’

‘I don’t know.’ She dipped the lace down a little further. ‘But I don’t see a man, do you?’

I peered over the lace. There were two men, but they wore overalls and were busy. The girl who had appeared from the back of the van continued to stand on the pavement. She was small and round and very pale, like a giant white pebble, and was buttoned into a raincoat right up to her neck, even though we hadn’t had rain for three weeks. She pulled a face, as though she were about to cry, and then leant forwards and was sick all over her shoes.

‘Disgusting,’ I said, and took another scone.

*

By four o’clock, she was next to me at the kitchen table.

I had fetched her over because she had sat on the wall outside her house, looking as though she’d been misplaced. Mrs Morton got the Dandelion and Burdock out, and a new packet of Penguins. I didn’t know then that Tilly didn’t like eating in front of people, and she held on to the bar of chocolate until it leaked between her fingers.

Mrs Morton spat on a tissue and wiped Tilly’s hands, even though there was a tap three feet away. Tilly bit her lip and looked out of the window.

‘Who are you looking for?’ I said.

‘My mother.’ Tilly turned back and stared at Mrs Morton, who was spitting again. ‘I just wanted to check she’s not watching.’

‘You’re not looking for your father?’ said Mrs Morton, who was nothing if not an opportunist.

‘I wouldn’t know where to look.’ Tilly wiped her hands very discreetly on her skirt. ‘I think he lives in Bristol.’

‘Bristol?’ Mrs Morton put the tissue back into her cardigan sleeve. ‘I have a cousin who lives in Bristol.’

‘Actually, I think it might be Bournemouth,’ said Tilly.

‘Oh,’ Mrs Morton frowned, ‘I don’t know anyone who lives there.’

‘No,’ Tilly said, ‘neither do I.’

*

We spent our summer holiday at Mrs Morton’s kitchen table. After a while, Tilly became comfortable enough to eat with us. She would spoon mashed potato into her mouth very slowly, and steal peas as we squeezed them from their shells, sitting over sheets of newspaper on the front-room carpet.

‘Don’t you want a Penguin or a Club?’ Mrs Morton was always trying to force chocolate on to us. She had a tin-full in the pantry and no children of her own. The pantry was cavernous and heaved with custard creams and fingers of fudge, and I often had wild fantasies in which I would find myself trapped in there overnight and be forced to gorge myself to death on Angel Delight.

‘No, thank you,’ Tilly said through a very small mouth, as if she were afraid that Mrs Morton might sneak something in there when no one was looking. ‘My mother said I shouldn’t eat chocolate.’

‘She must eat something,’ Mrs Morton said later, as we watched Tilly disappear behind her front door, ‘she’s like a little barrel.’

*

Mrs Creasy was still missing on Tuesday, and she was even more missing on Wednesday, when she’d arranged to sell raffle tickets for the British Legion. By Thursday, her name was being passed over garden fences and threaded along the queue at shop counters.

What about Margaret Creasy, then? someone would say. And it was like firing a starting pistol.

My father spent his time stored away in an office on the other side of the town, and always had to have the day explained to him when he got home. Yet each evening, my mother still asked my father if he had heard any news about Mrs Creasy, and each evening he would sigh from the bottom of his lungs, shake his head, and go and sit with a bottle of pale ale and Kenneth Kendall.

*

On Saturday morning, Tilly and I sat on the wall outside my house and swung our legs like pendulums against the bricks. We stared over at the Creasys’ house. The front door was ajar, and all the windows were open, as if to make it easier for Mrs Creasy to find her way back inside. Mr Creasy was in his garage, pulling boxes from towers of cardboard, and examining their contents one by one.

‘Do you think he murdered her?’ said Tilly.

‘I expect so,’ I said.

I paused for a moment, before I allowed the latest bulletin to be released. ‘She disappeared without taking any shoes.’

Tilly’s eyes bulged like a haddock. ‘How do you know that?’

‘The woman in the Post Office told my mother.’

‘Your mother doesn’t like the woman in the Post Office.’

‘She does now,’ I said.

Mr Creasy began on another box. With each one, he was becoming more chaotic, scattering the contents at his feet and whispering an uncertain dialogue to himself.

‘He doesn’t look like a murderer,’ said Tilly.

‘What does a murderer look like?’

‘They usually have moustaches,’ she said, ‘and are much fatter.’

The smell of hot tarmac pinched at my nose and I shifted my legs against the warmth of the bricks. There was nowhere to escape the heat. It was there every day when we awoke, persistent and unbroken, and hanging in the air like an unfinished argument. It leaked people’s days on to pavements and patios and, no longer able to contain ourselves within brick and cement, we melted into the outside, bringing our lives along with us. Meals, conversations, discussions were all woken and untethered and allowed outdoors. Even the avenue had changed. Giant fissures opened on yellowed lawns and paths felt soft and unsteady. Things which had been solid and reliable were now pliant and uncertain. Nothing felt sure any more. The bonds which held things together were destroyed by the temperature – this is what my father said – but it felt more sinister than that. It felt as though the whole avenue was shifting and stretching, and trying to escape itself.

A fat housefly danced a figure of eight around Tilly’s face. ‘My mum says Mrs Creasy disappeared because of the heat.’ She brushed the fly away with the back of her hand. ‘My mum says the heat makes people do strange things.’

I watched Mr Creasy. He had run out of boxes and was crouched on the floor of his garage, still and silent, and surrounded by debris from the past.

‘I think it probably does,’ I said.

‘My mum says it needs to rain.’

‘I think she’s probably right.’

I looked at the sky, which sat like an ocean above our heads. It wouldn’t rain for another fifty-six days.