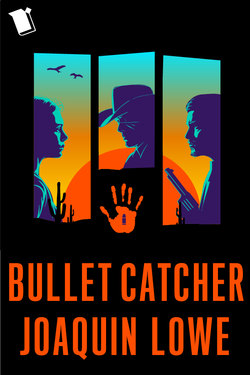

Читать книгу Bullet Catcher: The Complete Season 1 - Joaquin Lowe - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWhy just have this ebook when you could get the audiobook, too? To get the bundled text and audio for free, visit serialbox.com/redeem and use the code bulletcatcherebookaudio.

Episode 1

Immaculate

1.

It’s late at night when the memory comes for me, like it always seems to when the relief of sleep is ready to draw me under. The fire. I recall it as a heat on my face, a deep, quick voice that might be my father’s, my brother’s skinny arms around me, the glass of the windows blowing out, explosions that for the longest time I thought were fireworks. But they were gunshots; I know that now. The curtains going up like they were made to burn. The thick smell of smoke. Then darkness.

All I can do is lie on my cot in the corner of the washroom and wait for the memory to burn itself out. The room is small and square. Sand oozes up between the splintery floorboards. There’s the washbasin where I spend most of the day, and there’s my beat up writing desk in the corner, buried in books bought or stolen from traveling sellers.

Memory is a monster, far worse than anything lurking under a bed. I rub my eyes, slap my cheeks, anything to fight it off. But it’s no good. So I close my eyes and dig down deep into the past, trying my best to remember the good times in between the bad.

I think of my brother, Nikko. I think of the old stories he used to tell me. Of bullet catchers and gunslingers. Of good versus evil. In Nikko’s stories, good always won. I think of our parents’ old homestead, before the fire. I think we were happy then, but I was too young to know for sure. So young that when I try to imagine my parents’ faces, the image is blurred like a washed-out photograph. And then there’s the monster again, coming for me in the memory of the orphanage, in the glowering faces of the Brothers and Sisters who took us in.

“Immaculada Amaya Moreno!” the Sister yelled. “Get over here now!”

And there I am, peeking out from behind my brother. He was bigger than me and good to hide behind.

“Imma,” I said. “Call me Imma.”

The Sister grabbed me by the arm and hauled me in front of some fat old man, the latest prospective adopter. Some who came to the orphanage wore the nervous expressions of hopeful parents, but mostly they were people looking for cheap labor. Small hands are good for watch-tinkering or bullet-making. Small fingers are useful for polishing the inside of shell casings.

“This one’s ready for immediate adoption to a good home,” the Sister said. The fat man grabbed my hands and checked my fingers. Held me by the jaw and pulled down my lip and examined my teeth and the whites of my eyes like he was buying a farm animal.

“Too skinny,” he said. “She looks ready to keel over.”

“You’d be getting her at a significant discount,” the Sister said. But the fat man just snorted and moved on down the line, examining the other orphans. I hid back behind Nikko and he put his arm around me.

Back then, Nikko didn’t have much more meat on his bones than I did. He was starved-looking, cheeks pasty and sucked in, his smile crooked and forced. But he was always the strong one. He had a sorry little mustache that I remember him being so proud of. Whenever I think of him walking around with his shoulders back and his chin up to show everyone his new mustache, looking like a dead caterpillar stuck to his upper lip, it makes me smile, a smile so big my dry lips split and I taste copper. It’s my second favorite memory of my brother.

One day, he took me by the shoulders, stared straight into my eyes, and said, “Imma, after I get out of here, I’m going to join the bullet catchers. And all the wealthy families and banks and shop owners are going to want to hire me as their bodyguard.”

“What’ll happen to me?” I asked, my voice small and squeaky.

“I’ll earn enough money to get you out, too. I’ll buy a whole block of apartments in a wealthy town and we’ll live like royalty.” And I believed him. I loved so much the person he was going to be that my eyes would cloud over and I’d smile big, probably the biggest I’ve ever smiled, a smile that showed off all my missing baby teeth. Nikko was a dreamer. That’s my favorite memory of him.

I was nine the last time I ever saw Nikko. He had just turned fifteen, and he was proud of every one of those years. The night of his birthday, I helped him tie bedsheets together for a rope to climb out the window of our dormitory. We slept in a large room, crammed with rusty iron bunk beds and the sounds and smells of hundreds of orphaned children sleeping. He flung the bleached white sheets out the window and the full moon made them glow. The evening was so bright that I could see for miles into the desert. Nikko grabbed me by the shoulders the way he always did when he was excited and said, “I can’t take you with me now. You’ll slow me down and we’ll get caught. But I’ll come back for you.”

“Promise me,” I said, my voice breaking.

He looked at me and said, “I promise.” And I believed that, too, even though I cried as he slipped through the window and down the sheets.

I waited for him by that window every evening for three years, but I never saw my brother again. One day, Dmitri came looking for cheap labor and took me away to Sand. He put me to work behind the washbasin. For years I had to hold back tears, believing that when Nikko finally rode back to the orphanage, head up, his shoulders square and strong, a bullet catcher, he’d find me gone and not know where to look.

• • •

It’s been six years since then. I’m as old as Nikko was the day he hugged me and escaped into the desert. I’m fifteen and I know better than to cry. Now I know he never made it back to the orphanage. I know he died. Maybe the very day he escaped. If not from heat, then by marauders. Or maybe he was hunted down by coyotes, picked over by vultures. Before I was adopted, I saw flu and hunger take many children. At least Nikko died under the big sky of the desert and not in the orphanage infirmary. Now I know that in the end, death is a kind of escape.

And again the monster rears its head and I know there will be no fighting it off tonight. I untangle myself from the sheets, pull on a shirt and trousers, and shrug into my old frock coat. Stuffing my pockets with bullets, I grab my gun and head out into the desert to practice my aim.

In the Southland everyone has a gun, and I’m no exception. Though I’ve never shown it to anyone. It’s not exactly a gun someone can be proud of. It’s a lady’s pistol, tiny so as to fit under a bustier or corset or harnessed to a thigh, concealed under a dress. The space between the trigger and finger guard is so narrow most men wouldn’t be able to squeeze the trigger with their fat, stubby fingers. It’s low caliber, completely inaccurate, and a little bit of a curiosity. It has four barrels and holds four bullets: a barrel for every shot. Or that’s the way it’s supposed to work.

I bought the gun off a traveling merchant who’d stopped one afternoon to wet his whistle in the saloon. It was in piss-poor shape, rusted tight and clogged with sand.

It took me a while—lots of nights poking around under the lamp, the oil burning low and casting flickering shadows along the walls of my room—but I managed in the end to get it apart. I cleaned and oiled it. Salvaged parts. I got one barrel working. It’s a one-shooter. Which is a little scary, having only one bullet between life and death. But it’s better than nothing.

Overhead, the moon glows like a second sun, casting silver light and long shadows down Main Street. In Sand, Main Street is little more than a dirt track that runs between the ramshackle rows of storefronts. Potholes. Horse dung. Unspent bullets glittering like pennies in the gutters. Out here, where every little thing is precious, where water is a luxury, bullets are cheap. I pull my coat close against the cold desert night.

Just outside the town limits a rusted old sign, swinging on its hinges, reads:

WELCOME TO SAND: POPULATION 500

Maybe once upon a time. Half those people must be buried in that mound of dirt we call a cemetery. Little more than rotten wood crosses surrounded by chicken wire to keep out the coyotes.

I walk into the desert that goes on forever, golden and featureless, so that if you look in the right direction, away from the mountains in the south, you can see the curvature of the earth. That grand openness can be terrifying, more dangerous than a man with a gun. They both promise the infinite. But the gun will send you there faster.

The only things that manage to grow all the way out here are cacti and scrub brush, brown and thorny. I make my way to the outskirts most nights to practice my aim on the cacti, which in the half-light of the moon can resemble a person—skinny, bent, and water-starved, like everyone else out here.

When we were young, Nikko and I would play gunslingers and bullet catchers. I would pretend to chase Nikko around, firing make-believe bullets from the tip of my finger. Nikko always played the bullet catcher. He’d pantomime snatching the bullets from thin air. He’d catch an invisible bullet in his teeth. He’d take my imaginary bullets and bend them back at me, like a real bullet catcher would. And for my part, I’d always make sure he got me, right in the gut. I’d stagger and moan and collapse. Dead.

These nights, when I practice my aim, I always imagine the reedy figures of the cacti as a pack of menacing gunslingers come to get me. I draw a bead on one and fire. There’s the bang of the gun, the sulfur smell of smoke, the ping of the shell, the dry sound like wind through brush as the bullet takes a chunk out of the cactus. I have to reload after every shot, and I miss a few times, but in the end, I get them all. I only stop when my pockets are empty of bullets. My hand buzzes with the spent energy of the pistol. The moon hangs low on the far side of night.

Sand is an old mining town, and those who live here are the fevered few still clinging to the dream of striking it rich. We have every kind here: silver and gold miners, coal, metal ore. But the only ones who seem to turn any kind of profit are the water miners. Glorified well diggers, really. But then again, way out here, they have to dig deeper than anyone else. And water is the rarest and most essential of all the things hidden beneath our feet.

Walking home, I pass the miners heading out to their claims. Many of them are on foot, dragging the toes of their boots in the soft sand. But some have horses and wagons to carry their gear. There’s even a motorized buggy or two, coughing dark exhaust in the colorless dusk. I lower my eyes and pull my coat tight around me. It’s no good being a girl in a place like this, all by yourself, but I’m small and in the early morning there is just enough darkness to sneak back unnoticed.

In town the streets are waking to life. I hurry along the boardwalk, duck down the alley beside Dmitri’s, and slip in through the back door. In my room I undress and collapse onto my cot. There are still a couple hours before I need to be up. I close my eyes and drift into a short and empty sleep.

2.

The day breaks like a fever over the low rooftops. Dmitri wakes me with a slap, points to the dishes already stacked in the washbasin from the breakfast shift, and says, “Get your ass in gear.”

I pull on my clothes, go outside, and fill a bucket with sand from the alley. At the washbasin, I scoop up some of the sand with a cloth and start scratching the flecks of food from the plates. What people don’t know is that sand is hard, unbreakable. It’s already been broken down as much as it can be. Sand will grind you down and bury you. So, yes, sand is good for washing dishes. Good thing, because clean water that doesn’t taste and smell like lead or snakebite or piss is hard to come by in this town. Water that hasn’t been recycled a hundred times over is a luxury.

And so the day goes. I clean and stack the dishes. They pile up again. There are days when you just can’t get out from under all the dirty glasses and plates. Sand is light on people but heavy on drunks. And snakebite is the drink of choice. They distill it from the green slime of the nightsnake succulent, which has no problem growing all over the Southland. The green alcohol smells like the stuff the old drunken doctor at the edge of town uses to clean gunshot wounds, and it doesn’t taste much better. The destitute arrive in the morning and don’t leave until Dmitri kicks them out at closing time. They buy their snakebite on credit and pay it off by collecting rewards on bounties or doing odd jobs they pick up in the saloon.

In the afternoon, before the miners return, there’s a lull. I drop the rag in the basin and go out back, into the narrow alley between the saloon and the sundry shop that sells dried jerky and pathetic strips of dried fruit that grew who-knows-where. There’s not a single tree of any kind in Sand. At the end of the alley, I hug the wall and peer out down both ends of the street. This time of day, when the sun is just starting to sink, no one is outside unless they have to be. It’s hottest in the afternoon, when the sun is orange and purple, like an angry wound. There’s not much to venture outside for anyway. Besides the sundry and general store, there’s the dead-broke bank, the jail that only houses drunks sleeping one off, and the stables with their spindly, useless horses. If you aren’t a miner, odds are you wait out the heat of day in Dmitri’s or the cathouse at the outskirts of town.

The sun never shines into the narrow alley, so it’s always a few degrees cooler than everywhere else. Pressing my back against the wall, I sit in the soft sand and rest my eyes. Dmitri’s is hot and stifling, thick with sweat and cigar smoke. The alley is an icebox by comparison. I like to come out here when I have a break or if there’s a tussle in the bar. But drunks take to stumbling down here after Dmitri’s kicked them out, and since the drunks are easy marks, the alley is sure to hold at least one villain: at best a pickpocket, at worst someone feeling murderous. So I rest in the coolness of the alley with my eyes half open.

There’s a commotion from the street. Popping to my feet, I wrap my fingers around the handle of my little gun, tucked into my waistband. It’s hot and cold at the same time. It makes me feel brave. A few men have emerged from the saloon, swaying back and forth. They sing off-key, and can’t quite agree on the song. Despite their good humor, I don’t trust them, not in a place like Sand. Ducking back into the shadow of the alley, I hold my breath and wait for them to pass. They walk by and don’t notice me. I let out my breath.

“Imma, you scoundrel! Where the devil are you?” Dmitri yells from the back door of the saloon. Cursing, I skulk back to the washroom to tackle another stack of dishes, reeking of bad cooking and stale snakebite.

• • •

The rhythm of washing can be hypnotizing. It has the power to grind down your thoughts the way time grinds down a mountain. My mind empties. Only when the sun sinks low in the sky and the light slants into my eyes do I rouse from my stupor. By then the glasses, spider-webbed with scratches, are clean and stacked chin-high.

Stretching my back, I step away from the washbasin. Rest against the doorframe between the bar and my room and watch the barflies, the men in big hats playing cards for pennies, the lonely gunslingers passing through town on their way to someplace else, spinning their guns on their fingers for the girls turning tricks. That’s when the stranger appears. He pushes through the batwing doors, looking like a tornado the way the sand spins around him, the way his brown, threadbare coat billows around his thin body.

All eyes turn on the stranger. The saloon goes dead silent. Not for long, just enough for the old hinges on the swinging doors to creak twice. Then the noise starts up again, each voice louder than the next, the clack of bootheels on the old wood floor, the clatter of drinks. I watch, absently working the sand into a dirty glass with my rag.

The stranger crosses the saloon and sidles up to the bar. He holds up two fingers. Even from where I’m watching, I can make out his calluses and scars, dusty mountain ranges running every which way across his skin. Dmitri pours him two fingers of snakebite.

In the Southland there’s an unspoken rule that when you settle down for a drink in a saloon, you put your gun on the table. It’s a sort of peace offering. It says, I’m not here to make trouble. I’m just here to drink. And it establishes the pecking order in places like this. The person with the biggest gun is boss. But the stranger isn’t wearing holsters. He doesn’t have a bandolier and he doesn’t put a gun on the counter. Dmitri eyes him nervously, but says nothing.

I press myself closer to the doorframe, making myself invisible. Easy when you’re small, skinny like a knife. The stranger’s eyes flick from his drink to me, fixing me with a stare that pierces me to the core. In this mercury-popping heat, my heart freezes. No one sees me. Not when I don’t want them to. I’m the unnoticeable girl. It’s my power. It’s a good power. But the stranger sees me. From under the wide brim of his hat, his eyes peer out like the moon on a bright day: white and pale blue and almost invisible. His eyes bore into me, then he lifts his drink, sips, and, like that, I’m forgotten.

“Imma! What do you think you’re doing?” Dmitri hollers over the din of the saloon. His voice shakes the glasses on the bar. Everyone stops what they’re doing and looks up. His voice commands attention, everyone’s but the stranger’s. He doesn’t move a muscle.

And then Dmitri’s standing over me. He grabs the glass from my hands and holds it up to the light.

“You press too hard,” he says. “You’re ruining my glasses.”

“They’re cheap glasses.”

“Cheap!” he yells. “You’re the only thing I own that’s cheap!” He swipes me across the face with the back of his hand. Hard enough that his nice straw hat falls off his head. The blow drops me to my knees, but I stand up as quick as I can. He raises his hand to hit me again, but stops, picks up his hat, dusts it off, and goes out to tend bar.

I shake away stars, stagger to the washbasin, and look at the bruise developing across my cheek in my reflection in the pint glass. But it doesn’t hurt. No one can hurt me—I just bruise easy. It’s another one of my secret powers: fast-developing bruises. Once anyone sees the yellow-purple blotches developing they always let up. I pick up my rag, fill the glass with sand, and scratch the hell out of it.

From the far end of the saloon comes the screech of chairs pushed back quickly, the clatter of a table overturning. Stealing a peek into the bar, I see cards fluttering through the air like dying lightning bugs. Two men stand toe to toe. The first man has his guns drawn, aimed meaningfully at a second man’s chest.

“You trying to cheat me?” says the first man.

“You the cheat,” the second man growls. His eyes are yellow, his skin pallid from too much snakebite. “I won that silver fair and square!” His guns lie on the ground, a few feet away, among the spilled cards and scattered silver.

“Either way, you ain’t walking out with it.” The click-click of the hammers being cocked fills the otherwise silent barroom.

The second man’s eyes flick to his guns on the floor, and he says in a calmer tone, “Fine. Long as I get to walk out at all.”

The first man lowers his guns. The second man seizes his moment, diving for his guns. There’s a moment when everything is still. The air buzzes. Then the bar explodes in gunfire. The first man, grizzled and unkempt, is faster than he looks. He ducks behind the upturned table, unloading his irons. The patrons hit the deck. Glasses of snakebite explode. A man jerks back as a bullet passes through his cheek and out the top of his head. He crumples to the ground. And in a moment it’s all over. The second man lies on the floor. Blood leaks from his mouth and the hole in his chest. He wheezes and feels for his gun, just out of reach. The first man stands, dusts himself off, walks over to the bleeding man, and steps on his wrist. He applies pressure until something pops. The second man lets out a strangled gasp and the first man puts a bullet in his head.

Then the saloon is full of the sound of chairs and tables being righted. The patrons growl curses and prayers in lowered voices. Two customers haul the dead men out into the street and roll them into the gutter. A slick of blood trails out the door. Dmitri emerges from behind the bar with a bucket and scatters sawdust over the stain.

And then I notice the stranger. He hasn’t moved. Not a muscle. He sits on his stool and stares through the mirror on the other side of the bar. The glass is riddled with bullet holes on either side of the stranger, but the glass before him is unbroken.

That’s when I know what he is.

And I’m not the only one who’s worked it out. Things have just started calming down when a man comes up behind the stranger and stares at his reflection in the mirror. He’s tall, broad as a barn. His face is dark, with three scars on each cheek that travel from his nose to his ears. At first I think he’s just snakebit, but his eyes are narrowed and serious, and he stands straight and sober.

“I know you, bullet catcher,” he says.

For a time the bullet catcher doesn’t say a word, doesn’t move. Then, calmly, he picks up his drink, finishes it in a single gulp, and says, “There are no more bullet catchers.” He speaks in the voice of the desert: that stillness right before the wind picks up and blows everything to hell. If you’re caught up in one of those sandstorms you’re as good as dead. The sand gets going so fast it blows right through you like a million tiny bullets. The sand doesn’t care if you’re made of flesh or stone.

“I know a bullet catcher when I see one. I killed plenty during the war.”

The bullet catcher stands and drops a silver coin on the bar. He looks the scarred man up and down and says, “You’re a bit young to have seen much fighting, but I’ll be moving on just the same.” He tips his cap. The only sounds are his boots as he crosses the floor and the rusty hinges singing as the doors swing open and closed. All I can do is watch, my head peeking up just above the counter.

I turn to look back into my little room, at my meager belongings, my sorry life. I think of Nikko, the way I let him go so easily because I was sure he would come back for me. But in this life you can’t wait around for anyone. If you want something you have to take it. I learned that the hard way. And right now, all I want is to be out of here. I want to be free of Dmitri and his adoption papers like chains, shackling me to this washbasin. I want to be free like Nikko was, even if his freedom only lasted a night and a day.

All eyes are on the scarred man, waiting to see what he’ll do. I rush back into my little washroom. I grab what food I have—a couple handfuls of dried meat and fruit—empty the yellow water from the recycler into a skin, and throw everything into a pack. I untie my apron and pull on my coat. I stow my gun in the breast pocket, fill my other pockets with bullets, and sling the pack over my shoulder. It takes only a minute to pack everything I own, besides my books, which are too heavy to carry. In the end, my escape is easy. Maybe I had been planning it all along. Maybe I had just been looking for my chance. Nikko ran away from the orphanage to chase the bullet catchers. Now I am off to chase one of my own. I give my sorry little room one last glance and smile at the thought that I’ll never see it again. And then I run back out into the saloon.

The scarred man stands by the bar, looking like his girl stood him up. Finally, he sticks his thumbs in his belt and marches out the door. The patrons crowd after him. And there’s Dmitri’s big straw hat hanging on a peg behind the bar. I grab it, pull it low over my eyes, and blend into the crowd. I’m the unnoticeable girl again, a good foot shorter than the next shortest person.

The townsfolk line Main Street. The bullet catcher’s back is to everyone as he walks away. The scarred man ambles to the center of the street and squares himself to the bullet catcher, who’s nearly out of range. The scarred man takes off his long, dark duster and drops it in the dirt. He has two of the biggest, shiniest revolvers I’ve ever seen. The townsfolk see them too and gasp. But I know better. When something’s shiny it means it damn never gets any use. All of a sudden this guy doesn’t seem so big or bad. He stands with his legs apart. His fingers tickle the handles of his shooters.

“Turn and face me, bullet catcher!”

But the bullet catcher just keeps on walking. Drops of sweat, big as marbles, develop on the scarred man’s forehead. He has to do something or he’ll look a fool. Jokes and murmurs roll through the small crowd.

Pushing through the people, I duck into the alley and run down the side street, fast as I can, trying to catch up with the bullet catcher. I turn the corner of the last building as the shots ring out, two loud bangs that turn the air white. The bullets must be as big as cannonballs to make a noise like that. Fire into the air with those guns and you could make craters in the moon. I hit the ground. It’s instinct. Stray bullets are a problem in towns like Sand. You think there’s so much open space and so few people that the odds of getting hit by a stray bullet must be damn near impossible, but it seems to happen every day. I look up through the dirt, puffed up in a cloud around me from when I hit the ground, and watch the bullet catcher spin, his hands a blur. He moves so fast I think I may be imagining it, because a moment later he’s just walking off again on that same line out of town, like nothing in the world can break his stride. Picking myself up, I run out into the street. The man with scars on his cheeks lies on his back, like he’s making an angel in the dirt. His two shiny revolvers glitter at his sides. They won’t be there for long. As soon as the townsfolk get over the shock of seeing someone bend a bullet, they’ll descend on the fallen man like vultures, whether he’s dead or not.

Ahead of me is the open desert, hot and merciless. Behind me is Sand. I don’t turn back; I don’t say goodbye. The bullet catcher carves a straight line through the desert, walking toward the distant mountains.

And I follow.