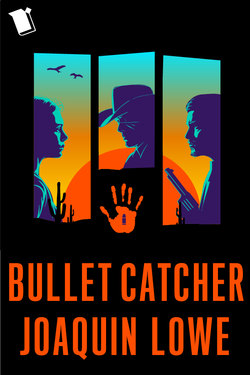

Читать книгу Bullet Catcher: The Complete Season 1 - Joaquin Lowe - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEpisode 3

The Bullet Catcher’s Apprentice

1.

It’s raining when I come to. I smell the rain before I open my eyes. I hear the rain in my dream that is not a dream, but a memory of rain. Nikko and I play in the mud that minutes before was burned desert. Our parents sit on the porch, Father for once not grumbling about the crop withering in the sun. Mother comes down the porch steps to play with us, muddying the hem of her skirt. Father smokes and smiles, a little.

I try to stay in that memory of home. The image of my mother and father is sharper than ever before. My mother wears a crooked smile because in that moment she’s truly happy, but she can’t forget the sadness of the empty desert. It’s a hard life out there. So she smiles with half her mouth and frowns with the other. Father is stoic, strong, square-shouldered, and looks like I remember Nikko looking, only all grown up, and with eyes that are deep set and dark and tired.

When I manage to sit up, I’m not looking at the shabby warmth of the old homestead, but into the clearing, from inside the bullet catcher’s tent. The rain patters on the canvas roof. The air smells of pine needles and earth.

I am stiff all over, and my chest is dressed in bandages, clean and bright white except for the perfect red circle just above my right collarbone. My right arm is tied to my body so I can’t move it. Besides the stiffness, there isn’t much pain, though I’m wrapped so tight it’s hard to breathe.

This is my first rainstorm since childhood, and despite everything, I can’t force down that deep, long-forgotten wonder that used to accompany all new things. On my hands and knees, I crawl out into the rain. I lie on my back in the mud. I close my eyes and open my mouth and drink in the cool rainwater. It is the cleanest, coldest water I’ve ever tasted. It’s the most water I’ve drunk at one time, and even though it hasn’t been so long since I was shot, I feel vital and alive in a way I never have before.

I lie on the ground and drink until my belly is full and I can’t drink anymore. Then I just lie there and let the cool rain pitter-patter on my sunburned skin. When I open my eyes the bullet catcher is standing over me, looking down.

“Only children and pigs play in the mud,” he says.

“But it’s raining. It’s actually raining.” It’s all I can think to say to the man who put a bullet in me. Who then dressed my wounds—it could only have been him—and let me rest in his camp while I healed. If I were keeping score that would make it twice he’s saved my life and once he’s tried to kill me. Does that mean he doesn’t want me to die or that he owes me one? The wound pulses with new pain, like it recognizes the man who made it.

The bullet catcher looks up at the sky, as though to confirm that it’s raining. He grunts and ducks into the tent. I lie in the mud, afraid to move, until he says, “If you stay out in the cold your wound will become infected and you will die of fever.”

Only when I’m back inside the tent do I start shivering. The bullet catcher points a bony finger to a quilt and I wrap it around my shoulders.

“You’re muddy,” he says. “When you’re healthy enough, before you leave, you will go down to the lake and wash the quilt and your dressings.”

A drunk at Dmitri’s once told me, “You don’t know what kind of person you are until you’ve been shot. After that you either jump at any loud noise or you become brave in the face of anything.” All I know is that right now I’m not afraid of the bullet catcher. And I’m not leaving.

“No.”

The bullet catcher sits and crosses his legs. He grinds his jaw that’s crisscrossed with scars.

“No?”

I clear my throat. “I’m not leaving.”

“That is not up for discussion. You will heal and you will leave, or you will catch infection and die, and I will bury you with all the others who have come to kill me over the years. Those are the only two paths before you.”

“I didn’t come to kill you.”

The bullet catcher pulls a blanket off a large chest in the corner. He opens the chest and it’s full of guns, some large and gleaming, like those of the gunslinger the bullet catcher killed in Sand, some old and rusted, some blood-splattered. My gun sits on top, small and pathetic-looking. How many guns does the bullet catcher keep here? How many people are buried out there, anonymous in the cold ground?

He picks up my gun and weighs it in his hand. His fingers are long and the gun is so small it looks like a toy. Then he tosses it to me. Its weight tells me the chamber is empty.

“There’s only one reason to draw a gun, young lady. To kill someone. Next time, keep it in your pocket.”

I look down at the gun in my hand, then back at the chest filled with dead men’s shooters. “Why didn’t you kill me?”

“You are young and foolish,” he says, closing and covering up the chest. “But someday, you may be old and wise.” A shadow crosses his face. “It is no small thing killing someone so young.”

The look on his face tells me not to pursue. Instead, I say, “I came here to learn from you.”

“Yet you pulled your gun on me,” he says, looking at me sideways.

I lie on my back, pull the quilt tight around me, and close my eyes. “I can’t go back to Sand,” I say. “I’d rather be dead.”

“There are many towns in the Southland,” the bullet catcher says. “You do not have to live in Sand.”

Propping myself up on my elbows, I look at him, then at the rain, still pouring down. “It’s not about where I live. It’s about what I want to do. I want to be a bullet catcher. It meant something to my brother.” I look back at the bullet catcher, who says nothing. “My brother’s name was Nikko. It was his dream to be a bullet catcher.”

“Are you in the habit of living other people’s dreams?”

His words take me aback. In all my years, I have never thought about what I wanted, other than to see Nikko again.

“If I can learn to be a bullet catcher it would be like bringing a part of him back to life.” It’s difficult putting into words things that were only feelings before. The bullet wound throbs and makes me lightheaded. I breathe out the pain and when I speak again I take all the emotion out of my voice, doing my best to mimic the bullet catcher’s calm. “My brother, Nikko,” I say. “He was very smart. He was strong.” I look at my hands; they are cupped as if holding the memory of him.

The bullet catcher lets out a sigh and says, “And he looked like you, only much taller. So you’re Immaculada.”

My face grows hot at the sound of my name. “Imma,” I say. “Call me Imma.” And then the gears start to turn, slowly, because not in my wildest dreams did I expect the bullet catcher to know Nikko, not really, let alone to know my name. I blurt out, “You know my brother!”

The bullet catcher looks out at the rain, coming down harder than before, turning the clearing to slurry. “I knew him,” he says, finally. “It was his dream to become a bullet catcher. But he was undisciplined, angry. He wasn’t interested in training. It was too painful for him.” The bullet catcher is silent for a time, just looking at the rain. “And in the end,” he says, “the training killed him.”

The air goes out of me. The canvas, pitter-pattering with rain, turns into a kaleidoscope of color. I lie back down and close my eyes. The sound of rain surrounds and envelops me. I hope it comes down so hard that it floods this place. I want the water to carry us down the mountain and throw us against the rocks until all our bones are broken and we are nothing but blood and torn skin and mud. I’ve been living with Nikko’s death for six years, but now, after this brief moment of hope, it’s like he’s died all over again.

“He spoke of you often,” the bullet catcher says beyond the sound of rain, his voice almost apologetic. Perhaps he says more, but his voice is indistinguishable from the rain, a white noise through which nothing else can penetrate.

• • •

I sleep without realizing it. There are no benefits to this kind of sleep, full of so much blackness. When I open my eyes the rain has stopped, but the smell of it hangs in the air, crisp and clean and earthy. The sun shines through the canvas, making the air golden and warm. The bullet catcher is outside, fixing his fire pit, drying his rocking chair.

“You passed out,” the bullet catcher says when I join him.

I nod.

“Your wound is bad. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

“You don’t have to make excuses for me.”

He merely nods again.

“How can I help?”

“The best thing for you is rest. You will heal quicker. Then you will leave. Same as before.”

“I’d like to help. To thank you.” Maybe it’s impossible to get him to train me. Maybe it’s a foolish child’s dream. But even so, there’s no way I’m leaving without him telling me everything he knows about Nikko.

The bullet catcher scans his camp, half destroyed by the rain, before resting his gaze on me. His eyes are soft, almost kind. “There is much to do. It will be hard work in your condition.” He pauses “But hard work is seldom without reward.”

2.

The bullet catcher doesn’t rest. He moves slowly, but constantly. Over the months that I spend with him, healing from my gunshot wound, I become his shadow. When he wakes before the sun, I’m right behind him. When he goes into the woods to check the traps, I’m there, asking questions. I’m there when he skins the fur from the wolves caught in the traps. I help as he hangs the hides in the sun to dry. He cuts the meat from the bone in a way that draws hardly any blood. He saves the bones and shows me how to suck the marrow from them. He salts and preserves the meat. Nothing of the animal goes to waste.

There are no seasons in the desert. The weather changes from hot to not quite as hot and then back again. Up on the mountain, fall slowly turns to winter. When the dawn breaks, brisk, with only the promise of light, I go down to the lake to bathe. I find a large smooth rock just beneath the surface of the water and sit. The thin film of ice breaks away as I disturb the water, so cold that I want to jump out and run for my clothes, run back to camp, where I know the bullet catcher will just then be feeding branches into the fire. So I take a large flat rock and balance it on my lap to keep me anchored. Like the bullet catcher, I find a small dimpled rock and scratch the dirt from my skin in little circles.

The skin where the bullet pierced me is pink and rough, but it’s finally closed. It still hurts when I breathe deeply, but the pain is only an echo of its former self. I pass my fingers over the scar, regretting how fast it’s healed. Every day, I’ve examined the wound in the old, cracked hand mirror the bullet catcher uses for shaving and ticked off the days in my mind. Soon he will force me out.

I’m still shivering as I head back into camp. The fire crackles. A pot of coffee boils and steams above it. The bullet catcher gives a curt nod as he heads down to the lake for his turn. By the time he returns the coffee is ready. He pours out two mugs and hands me one.

We’ve honed this routine over the months and, dare I say, I think he’s taken a shine to my being here, our little morning ritual of coffee and near silence before the work of the day begins.

He sips, sits in his chair, pulls out his pipe, and begins cleaning the bowl with a knife. “Your wound has healed,” he says. “It’s time you were moving on.” He packs the bowl with tobacco, lights it, and puffs a zero into the air.

“It still hurts when I breathe,” I stammer. I pull my shirt down one shoulder to reveal the spot above the collarbone where the skin is still raw.

He raises his hand to stop me and says, “You will have food enough and water to make it down the mountain. You helped with the hunting and preserving. You have earned your share.”

“I have earned more than that.” My face is hot despite the cool mountain morning.

He puffs calmly on his pipe and says, “You are young and without ties. I offer you enough food and water to get to town. From there you can go any direction you wish. You could even go north, out of the desert, for as few ties as you have to the Southland.”

“You talk like it’s a blessing to be an orphan.”

“There are blessings and misfortunes to every walk of life. The orphan is lonely, but weightless, and can fly anywhere. A person from a large family is tied to others, but also to the ground, and finds it difficult to travel.”

“And if I tie myself to you?”

“This is not the life for you.” He had been watching the smoky zeroes as they floated skyward and unraveled, but now he looks at me and says grimly, “Your brother came to understand that, but too late.”

“You’ve already been teaching me, whether you realize it or not.” I take a deep breath and say, “I’ve learned to trap, and clean wounds. I’ve learned to build a fire. I’ve learned so much.”

“This was your brother’s dream. Not yours. I advise you to find a dream of your own.”

“And what would you recommend? What opportunities do you think there are for a girl in places like Sand or any of the other one-horse towns in the Southland? Dishwasher? Bartender? Prostitute? I’d rather die.”

The bullet catcher studies me. Smoke curls up out of his nose. “You should know the consequences of the decision you are about to make. To be a bullet catcher is to be an outlaw. You will be hated. You will be feared. If you are lonely now, you will be lonelier still. You will most likely die young. There will be pain that I cannot describe.”

He looks at me, his eyes studying my face, judging every twitch and tiny reaction. “Now,” he says. “Does that sound better or worse than being a dishwasher?”

Though I know I shouldn’t, I look down at my boots. They’re polished and mended—another skill the bullet catcher has taught me in my time with him. I don’t want him to see how frightened I am by his words, just in case it shows on my face. I take a breath, summon my courage, look him in the eyes, and say, “It’s not about better or worse. This is what I want.”

“Have you ever heard of the merchant’s curse?” he asks.

I shake my head.

“The merchant’s curse is to get everything you ever wanted.”

“Doesn’t sound like much of a curse,” I say.

He looks at me for a long time, then simply says, “Very well.”

• • •

We wake before dawn each day. The squirrels and wood mice are still asleep; the foxes and wolves are still out on their night hunts. We stalk with them for a time. The bullet catcher leads, his steps silent and light so as not to break twigs and hoarfrost underfoot. I’m his shaky, half-asleep shadow, trailing loudly behind him. When the light breaks and the nighttime animals bed down, we are still out, tracking through the woods around camp. We aren’t hunting for anything in particular. The bullet catcher’s just testing me. Each morning, I’m sore, but stronger than the previous day.

“Exhaustion is good for focus,” he says. And I scowl and clamp my mouth shut to keep from cursing.

We get back to camp in time to see the sunrise over the eastern peak of the mountain. Winter is in full swing. And though the sun lights the sky a bright orange-purple, it does nothing to warm the morning. When we break into the clearing, the bullet catcher’s breath is slow and even; only his flared nostrils give away any sign that we just ran for miles through the craggy mountainside. I collapse in the dirt. I’m so tired my eyes water. The dirt sticks to my face, turning my skin the same color as the earth, and I wish I could just melt into the ground and sleep forever.

The bullet catcher ignores me and prepares to bathe, gathering up his scratching stone and rug to dry with. I crawl to the fire pit and begin arranging tinder onto the blackened remains of last night’s fire.

“What are you doing?” the bullet catcher asks from over my shoulder.

“Building a fire for breakfast.”

“Do not crawl in the dirt like an animal unless your legs have been shot out. And even then you should do your best to stand.”

I scowl into the cold campfire and struggle to my feet. “I can’t feel my legs,” I say. “They may as well have been shot out.”

“Then it is good practice.” He waits for me to finish preparing the fire and to pull out the flint before he says, “A bullet catcher does not eat with dirty hands.”

I drop the flint into the sooty dirt and can almost feel the hairs on the back of the bullet catcher’s neck standing on end. He glares at me, his eyes telling me to pick up the flint, to respect my tools, but I’m too tired to care. I stomp past him on my way to the lake, and as I’m passing him, I spit in the dirt by his boots. He doesn’t say anything. But hellfire flickers behind his eyes.

• • •

Back in camp, my hair is wet and freezing, but the bullet catcher has the fire burning. It warms my bones, soaked through with ice water from the lake. He’s fed up with me, so he says nothing when he grabs his things and goes down to the lake for his turn.

When the bullet catcher returns from the lake he starts breakfast. Today there is boar meat. The bullet catcher turns it on a spit. The fat crackles as it drips into the fire. And there are eggs, and greens I don’t know the name of, too. And the bullet catcher piles it all onto my plate because he says I’ll need my energy. Then he sits back in his chair with his own plate, heaped high with food, balanced on his lap. He cuts his meat slowly, eats slowly. I can tell it’s one of the few things he truly loves. It’s when we eat that we rest. Really rest. But after the morning exercise I’m starving. So I dig in, and it’s all I can do to keep myself from dropping my fork and knife and just eating with my hands. As I eat I watch the bullet catcher, studying him.

Now he catches me looking and raises an eyebrow.

I often wonder what the bullet catcher did during the war, especially toward the end when the gunslingers were hunting down the last of his kind. Maybe the gunslingers took him prisoner and tried to starve information out of him. And what about the scars on his back? They could be whip marks. They look a bit like the scars on Nikko’s back, from when the Brothers and Sisters would punish him.

“Why did the gunslingers and bullet catchers hate each other so much?”

“One believed in taking power with a gun and one did not.”

“That doesn’t seem like enough of a reason to hate someone so bad you wanted to kill them.”

“That’s the thing about hate,” he says. “There ain’t no sense in it.”

“Did you come up here to hide from the gunslingers? You know, during the fighting?”

“No,” he says. He takes a slow bite of his food. “Not at first.”

“When?”

He looks up and fixes me with his cool, blue moon eyes. But when I stare back at him and refuse to let it drop, he puts down his knife and fork and says, “I came up here toward the end of the war. We had lost, but some chose to keep fighting.”

“You deserted?”

“Yes, I deserted.”

“Weren’t you ashamed?”

“We had lost already. I didn’t see the point of also dying. Back then I believed that there were good deaths and bad. And I believed a good death was one with meaning.”

“And now?”

“Now I know that death is always meaningless. A clap followed by nothing.”

We are silent for a time. “What’s your name?” I’ve asked it every morning for the last month. The wind blows through the trees. The bullet catcher says nothing. I go back to my food. “When I die,” I say, “I want it to mean something.”

He sloshes the dregs of his coffee into the fire. It hisses and flickers. He stands and says, “It won’t.”

• • •

At the base of the mountain, where the ground becomes flat and even, the bullet catcher leads me through the practice steps, like a dance. He shows me where to place my hands and feet. He corrects me if my stance is too narrow or wide, if my hands are too high or low. He slows me if I’m too fast, quickens me if I’m too slow. He tells me to close my eyes and focus on breathing. Or he says to keep my eyes open and imagine gunslingers in the warbling line of the desert. He quizzes me on what position I would use if they were shooting at my gut, my legs, my heart.

The positions are second nature by now, and mostly the bullet catcher only tweaks my posture, putting his hand on mine, shifting it a half inch or so, or he’ll tap my shoulder and I know I haven’t turned enough to my imaginary gunslinger, that I’m providing too large a target. Or he’ll nudge the back of my leg with his toe, because my stance is too narrow and if I had to suddenly shift my weight, I’d lose my balance. At first, we would go through the steps in slow motion, but lately we’ve sped things up.

Usually he tells me where he’s aiming, giving me time to go through my mental checklist of positions, but today, he points the empty gun, mimes the recoil, but he doesn’t tell me where he’s shooting. I keep my eye on the subtle shifts in his aim, clear my mind, and let my muscles react.

“Visualize the bullets!” he instructs. “Even when the bullets are real,” he says, “you have to visualize them. Bullets move too fast for the eye.”

Finally, after hours of this, I double over at the waist, my hands on my knees, and suck at the air. The bullet catcher lowers his gun and walks over to me. He produces a skin of water, takes a swig, and hands it to me. I drink greedily.

“It’s time.”

“Time for what?” I ask. But the way he said it, I know it can’t be anything good.

The bullet catcher flicks open the chamber of the gun, loads a single bullet, and flicks it closed. Suddenly, the gun is huge and evil-looking, dull in the light of the moon rising over the desert.

The bullet catcher puts his hand on my shoulder. It’s heavy and warm. Even through my clothes, I can feel the multitude of scars lining his palm. “We’ve worked all day,” I say. “Let’s do it tomorrow.”

The bullet catcher shakes his head gently. His hand is still on my shoulder, radiating warmth. I look up at him and he’s smiling, like he’s suddenly got the knack of it. His smile is small, but like his hand, it radiates warmth. And I understand that he’s been where I am now, with his teacher’s hand on his shoulder, fear running through his spine. The bullet catcher judges my every mistake, but he does not judge my fear.

“It’s better to do it now,” he says, “when you are tired and your mind is clear. Tonight you will sleep well, knowing you won’t have to do this in the morning. There will be no thoughts of running away when fear gets the better of you.” He counts out the paces between us and turns. I imagine running away. I would run across the desert, all the way back to Sand. The bullet catcher reads my expression. He has seen and done all this before. He has encountered many different would-be bullet catchers. Brave. Cowardly. Full of hubris or disconsolate and unaware of their potential. Maybe he is thinking of Nikko. How he met this challenge, if he made it this far.

“First position,” he calls.

My mind is blank, but my muscles remember. They take first position, my right foot just ahead of my left, my toes slightly pigeoned, right hand up, left hand down, so they form a diagonal across my body. From first position I can adjust to wherever the bullet catcher aims. The bullet catcher doesn’t use first position anymore. He says that with enough practice, the positions become more relaxed, more natural. First position is just for beginners.

“Ready,” I call back, my voice shaking. My heart threatens to break out of my chest. I’m just a dishwasher. Is this how Nikko died? Is this what following in his footsteps means?

The moon has disappeared behind the clouds and the sky is a starless dome overhead. The gun in the bullet catcher’s hand glints silver. It’s cold and I’m sweating. My fingers tingle. Everything is silence. Then the bullet catcher raises the gun and pulls the trigger. The explosion is deafening. It obliterates the bullet catcher’s lessons in my mind.

I always imagined that a bullet catcher could slow and speed up time at will, that she has time to think how she will direct the bullet. Will she skip it across the ground like a stone across water or will she curve it back around to its shooter? Will she aim for the shooter’s gun to disarm him or will she hit his heart to kill him? But I’m a dishwasher, not a bullet catcher. Time does not slow for my sake.

I don’t see the bullet, can’t visualize it. It’s too terrifying to imagine. Then it hits, sending me sprawling to the ground, clutching my arm, the blood oozing through my fingers.

I squeeze my eyes shut. My legs bicycle in the dirt. There’s so much blood. Then the bullet catcher is standing over me. He kneels beside me and pins my shoulder to the ground to stop me writhing.

“Open your eyes, Cub,” he says gently. He’s never called me that before. What does it mean?

I shake my head. “You’ve killed me,” I squeeze out.

“No. It is only your pride.”

I force my eyes open and look at him. His eyes are upturned crescents, shining in the light of the moon that has reappeared over the desert.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

“There is no reason.”

“I failed.”

“Where did I hit you?”

He knows where. The blood is everywhere. The question is a test. “The arm,” I say. “Below the shoulder.”

“What did you forget?”

“Fourth position,” I grunt through the pain. It’s a difficult position. You need to raise one foot so only your toe touches the dirt, extend your arms out, one before you, the other backward, and balance on the ball of your planted foot.

The bullet catcher nods. He reaches down and pries my fingers from the wound. “The bullet bit you hard,” he says. “This will leave a good scar. It is important that the first scar is good.”

“This is the second one,” I say dreamily. I feel like I might pass out.

“This is your first as a bullet catcher’s apprentice.”

The encroaching delirium gives way to anger and I shake his hand from my shoulder. I get to my feet, and almost pass out from the adrenaline and loss of blood. I avoid the bullet catcher’s gaze as I grab the med kit and sit in the dirt facing away from him. I clean and stitch the wound myself. The bullet catcher wordlessly makes a fire to give me more light.

It takes me a long time, dressing the wound, and as the adrenaline wears off the pain and nausea come back with added intensity. But finally, I finish.

Back in camp, I bed down for the night without a word to the bullet catcher, and he leaves me be. The bullet catcher was wrong. I do not sleep easy. I do think of running away, driven not by fear, but by the thought that it’s all hopeless. All these years I wanted to be like my brother. I wanted to walk in his footsteps. But Nikko never became a bullet catcher.

But I don’t run away. I lie there all night, and by the time morning comes I’m resolved. I don’t want to be a bullet catcher because of Nikko. I used to think that if I could succeed where he failed I might, in some small way, keep him alive. But those are childish thoughts. And now I understand what the bullet catcher meant when he said I needed a dream of my own. If I’m going to become a bullet catcher, I have to do it for myself. I want to be a bullet catcher not because it’s easy, but because it’s hard. Because what makes it difficult makes it special. And I did learn one other thing: The bullet catcher won’t kill me. He wasn’t aiming to kill me, but just to teach me a lesson.