Читать книгу N*gga Theory - Jody David Armour - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

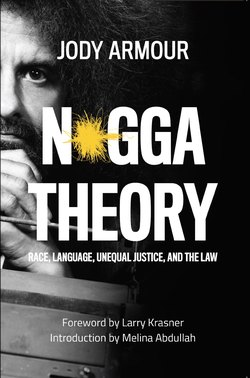

Nigga Theory: A Song of Solidarity

Call me a Nigga.

Call ME a Nigga: I utter these words as a political battle cry for the Black, damned, and forsaken—that is, for the staggeringly high percentage of poor black boys and men languishing in jail cells, for those selling drugs, gangbanging, or otherwise scrambling for survival and self-respect.

I say it because we have a fundamental divide that needs bridging. This divide is cultural fact as well as a social fact. It is an economic divide crossed by moral judgment. It is the divide between the haves and the have-nots, but it is also, for many, seen as a divide between the morally upstanding and the morally corrupt. This book will dismantle that distinction.

And it will dismantle it with Nigga Theory. So call me a Nigga With Theory. NWT.

—

Call me a Nigga is what language philosopher J.L. Austin would call a “performative”—a form of symbolic communication that performs a social action, a “speech act” that doesn’t simply say something—it does something1. Phrases like “I pledge allegiance” and “with this ring, I thee wed,” and “I promise” epitomize linguistic bonding performatives. Nonlinguistic ones include flags (like Old Glory), personifications (like Uncle Sam), and melodies (like instrumental versions of the Star-Spangled Banner and America the Beautiful). In political communication bonding performatives like these unify and rally individuals; they create collective social actors and forge social identities. And re-appropriating ugly racial epithets like “nigga” and “niggas” can turn them into forceful bonding performatives. Reviled and revered rapper Tupac Shakur bonded with black criminals by expressly linking “brothas,” “Niggas,” and “criminal gangstas,” or “G’s” in the following hook, from his solidarity dirge, “Life Goes On”2:

How many brothas fell victim to the street

Rest in peace, young Nigga, there’s a heaven for a G

Be a lie if told you that I never thought of death

My Niggas, we the last ones left.

Despite having no criminal record myself, I say call me a Nigga to perform my solidarity with and rally political support for black criminals and convicts: those in my family, those in the poverty-stricken neighborhoods down the hill from my own economically gated community, and those in cynically de-industrialized rustbelt cities like my hometown of Akron, Ohio, where crime goes hand-in-hand with concentrated disadvantage. I also say call me a Nigga to promote unity and assert solidarity among blacks across moral lines of good and bad, right and wrong, wicked and worthy. And because a grossly disproportionate number of the black criminals we judge to be bad, wrong, and wicked are poor, I utter this profane performative to promote a necessary political alliance: an alliance between the statistically less “crime prone” black bourgeoisie and the more “crime prone” black underclass.

—

The vilification of a “crime prone” underclass figures centrally in what I call “Good Negro Theory”: the values, beliefs, and assumptions that underlie efforts to morally and politically distinguish between law-abiding “good Negroes” and law-breaking “niggas.” In its place I offer “Nigga Theory.”

Earlier generations of civil rights advocates found that they were most successful—their rhetoric most effective—when they distinguished and distanced themselves from the most stigmatized elements of the black (for present purposes, disproportionately poor, law-breaking black) community and drew the attention of the public and policymakers to certain black people, namely, those understood by mainstream whites as “good,” “sympathetic,” and “respectable” (for present purposes, disproportionately better off, law-abiding black people). This political strategy—commonly called the “politics of respectability”—was practiced by civil rights era activists and rested on the belief that racial oppression can only be ended if black people prove to whites that they are worthy of respect and sympathy. Even if the basic social order is unjust and racist, this theory goes, blacks must show they look at the world through conventional moral lenses and aspire to the same moral codes as the white middle class.

Nigga Theory is a repudiation of Good Negro Theory and the politics of respectability on which it rests.

But first a quick word to those who might object. As part of my political practice, I have made my performative declaration, call me a Nigga, in many venues, under many different conditions. I have said it, or performed it, in prisons and intervention programs for juvenile and adult offenders; in black churches and before formal gatherings of black judges and justices; and in the company of scholars at conferences, in performing arts halls, university auditoriums, downtown law firms, alumni magazines, and on social media. In other words, I’ve vetted this invitation to bond with black criminals with three key audiences: 1) the objects of our criminal condemnations themselves, namely, the truly disadvantaged blacks who are doing time or still doing street crime; 2) the weightiest authorities on morality and justice in the black community, namely, the black church and judiciary; and 3) those who must morally assess black wrongdoers on juries, in legislative chambers, and at the ballot box, namely, ordinary Americans of all races and walks of life.

Some vehemently reject my use of the emotionally charged catchphrase, and they do so on one of two grounds. First, some contend that any sentence that wholeheartedly embraces the word “nigga” cannot be a progressive performative utterance and cannot unify Blacks or produce positive social change; I respond to their concerns in a chapter devoted to ordinary language philosophy and the N-word. Others object not to the word “nigga” itself but to my self-referential use of it—that is, they see the statement call me a Nigga as a claim that cannot be authentically uttered by a respectable law professor in reference to his own privileged black self. The following blog criticizing my exhortation succinctly captures this viewpoint and the righteous invective that often accompanies it:

Prof. Armour, I’ve met niggas. I know niggas. I have nigga clients. You, sir, are no nigga. First, you graduated high school, then you graduated college, then you became a professor. You’ve probably never even fired a gun, let alone killed anyone. Your son will never visit you in prison. You’ve probably never sold a single gram of cocaine, and I’ll bet a thorough inspecting would reveal no gang tats anywhere on your body. You drive a German sedan with GPS but not 22″ chrome wheels. You don’t receive public assistance, daydream about starting a record album, or have half-dozen illegitimate children you don’t support. You probably have a six-figure salary from legitimate sources. You are about as far away from a “nigga” as a black man can be. Hell, I may be more nigga than you.

So I say call me a Nigga despite not fitting this popular stereotype—despite my lack of a criminal record, my light-skin privilege (I’ve been called a yellow nigga, a sand nigga, and a Spic), my Ivy League diplomas, my respectable salary befitting the occupant of the Roy P. Crocker Chair at the University of Southern California Law School, my residence in the Black Beverly Hills, my three sons who attended exclusive private high schools and colleges, my respectable rims, my fluency in “talking White,” and my red-headed Irish Catholic mom. Thanks to my lighter shade, academic pedigree, chaired professorship, tax bracket, ZIP code, speech patterns, and mixed ancestry, I am not what cognitive science would call a “prototypical” nigga.3

If the sentence call me a Nigga were a statement of fact, or if the blood-soaked epithet on which it turns had a fixed meaning, which it does not, then perhaps I could not authentically utter it and perhaps its use could not produce “real” social change. But the boundaries of “nigga” (lower-case “n”) and “Nigga” (upper-case “N”), like most linguistic boundaries, are malleable and always up for grabs, and I, like many others, am repurposing the words as terms of art in an oppositional discourse that uses words as tools, tools that can accomplish two tasks, one critical, the other political: 1) I use “nigga” (lower-case “n”) critically, conceptually, and analytically to highlight and isolate and ultimately refute illegitimate and unreliable moral condemnations of disproportionately poor black wrongdoers whom many outside and inside the black community “nigger-” and “nigga-rize” and, 2) I use “Nigga” (upper-case “N”) politically to stand in solidarity with wrongly vilified black criminals and rally resistance to a common foe, namely, “tough on crime” “eye-for-an-eye” “lock ’em up and throw away the key” retributionists responsible for the disproportional incarceration of black criminals, especially violent ones. I say call me a Nigga to contest what that condemnatory word and concept mean, and through that contestation to unite law-abiding and law-breaking blacks and more generally to undermine the moral distinction between criminals and non-criminals of all races. This book rests on the basic premise that struggles over the meaning of troublesome and transgressive words and symbols can drive radical social change.

—

But I say call me a Nigga, first and foremost, to assert solidarity with and express love for a criminally condemned man whose conviction relegated him to the status of a nigga in the eyes of many and whose legacy lives in every word I speak or scribble about blame and punishment: I look at our criminal justice system through lenses ground and polished by his experience. I cannot think about legal writing without seeing a black man desperately click-clacking on a Royal manual typewriter on his cell floor, deep into the night, in search of his own salvation. That man, doing 22 to 55 in the Ohio State Penitentiary for possession and sale of marijuana: he was my dad. All that stood between him and a lifetime of iron bars and cell blocks and prison yards was word work—nothing but the Queen’s English he and that Royal keyboard could crank out. After teaching himself to talk and think like a lawyer from the warden’s own law books, he drafted his own writs and represented himself pro se through the state and federal court system, delivering his own oral arguments to appellate tribunals along the way, and ultimately vindicating himself in Armour v. Salisbury (492 F.2d 1032), a Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals case I now teach to my first-year criminal law students. #PoeticJustice.

My love for and sympathetic identification with this particular black convict makes me, according to the logic of those who seek to niggerize black criminals, a Nigger Lover. That logic makes my mom, grandmom, eight brothers and sisters, and everyone else who sympathetically identified with him, Nigger Lovers. Indeed, given the millions of moms, dads, sons, daughters, relatives, and friends who sympathetically identify with black criminals, including violent and serious ones, Nigger Lovers in this poignant and supremely ironic sense number in the millions. Indeed, it will be useful to make Nigger Lover a term of art, properly applicable to anyone who empathizes or sympathetically identifies with a black criminal, including those who are violent. The substantive criminal law requires that jurors convict only morally blameworthy wrongdoers, under the ancient legal maxim actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea—in Blackstone’s translation, “an unwarrantable act without a vicious will is no crime at all.” Under this mens rea principle, as it has come to be known, it is unjust to punish someone who commits an “unwarrantable act”—the actus rea—unless he acted with a “vicious” or wicked will. This requirement invites jurors to fully or partially excuse wrongdoers with whom they sympathize, and so a black defendant’s freedom in a criminal trial often rides on the ability of his lawyer to transform often racially resentful jurors into Nigger Lovers. Ironically, as a child I often heard other whites refer to my mom as a “Nigger Lover” for her participation in what many around her viewed as morally condemnable conduct: the dreaded commingling of gene pools called miscegenation. Of course, the commingling of black and white gene pools has been going on in America since its inception. White male slave owners violently injected their genes into the black population through the rape of black female chattel for hundreds of years under slavery. Nevertheless, the sight rankled many in the late 1950s and early 1960s: my Irish American mom, with her head full of flaming red hair, and my 6’8” barrel-chested black dad, the two of them looking like Lucille Ball and LeBron James, kicking along main street in stride—one, two—arms locked, unmistakably matched. The obscene thought of this big black man skinny-dipping in their European gene pool provoked racially resentful cops and prosecutors to railroad him.

I also say call me a Nigga to forcefully assert my solidarity with and love for the black boys I grew up with in Akron, Ohio, once home to all four major American tire makers (Goodyear, Goodrich, Firestone, and General Tire) and known as “Rubber Capital of the World.” Until, that is, tire makers took their unionized, good paying, low-skilled jobs to cheaper labor markets down South and overseas, leaving behind neighborhoods mired in joblessness, alienation, and crime. If the Midwest is America’s heartland, this nation suffered a myocardial infarction and gross necrosis in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s due to interruption of the job supply to this area. The destructive consequences of rustbelt necrosis never reached our family while my dad was a free man, but when he essentially got “25 with an L” (a sentence of 25 years to life) a week after my eighth birthday, his eight kids and wife went from a comfortable Cliff Huxtable and the “Cosby kids” standard of living to crumbs and roaches and rats. Most of the poor black boys I suddenly began running those cynically de-industrialized streets with have been convicted of criminal wrongdoing—especially the ones with ambition, backbone, and grit. That makes them, by the Black Criminal Litmus Test of a nigga—by our shared history, and by our bonds of mutual love and respect—“my Niggas.” In calling them my Niggas, I am saying that even though they meet the litmus test of criminal condemnation and I do not, and even though they are morally responsible for criminal acts that I have never committed, there is no real moral difference between them and me. All that distinguishes us is luck.

In my years writing these reflections on the power of linguistic bonding performatives like call me a Nigga to promote unity and political action, I inadvertently grew a vociferous nonlinguistic political performative on the top of my head: a lengthy, kinky, loud-and-proud Afro. Unabashedly nappy and self-affirming, big Afros in my youth represented the gravity-defying antithesis of the wind-flapping-in-your-hair white standard of beauty by which many black people’s full lips, broad noses, kinky hair, and dark skin were deemed inherently ugly. Many world cultures shared this negative view of natural black features and many black Americans internalized Eurocentric beauty standards, frequently referring to straight hair as “good” and their own naturally nappy variety as “bad”—fit only for lye and presses and weaves and relaxers. Thus, those who donned big “naturals” took so-called “bad hair” and contested its negative social meaning, inverting and transvaluing nappiness into a sensuous nonlinguistic bonding performative, the exact equivalent of linguistic ones like “Black is Beautiful” and “Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud.” Both the Afros and the slogans promoted social and political solidarity among black people in the mid-to-late 1960s, creating alliances of loyal individuals capable of producing change through unified social action. This is why Black Power proponents of that era—including members of the Black Panther Party and iconic political activist Angela Davis—routinely “uttered” big Afros as part of their oppositional political discourse.

Black Power proponents who donned Afros and used follicle fashion to protest undemocratic subordination were far from the first “radical” Americans to use the symbolic power of fashion to fight illegitimate assertions of power. This honor and distinction goes to the early revolutionist Philadelphia militiamen, who in the mid-1770s resisted putting on conventional uniforms, preferring instead hunting shirts, which they said would “level all distinctions” within the militia. In so doing, they were both struggling over the meaning of symbolic communication and using the symbolic force of fashion to bond together.4 This American political tradition of using the bonding force of fashion to rally resistance in the face of illegitimate assertions of power resulted in suffragette bloomers in the mid-19th century5 and, more recently, produced another forceful nonlinguistic performative: the hoodie. This article of clothing was worn by black 17-year-old Trayvon Martin on the occasion of his fatal shooting by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman, who claimed to reasonably believe that Martin posed an immediate threat of death, serious bodily injury, or “forcible felony.” After the killing, students, pundits, and politicians donned hoodies to stand in solidarity with victims of racial profiling and to bond with others who saw a miscarriage of justice in the failure of police to properly investigate the shooting or charge Zimmerman. Like “nigga” as a word and “bad hair” as a physical characteristic, a hoodie as an article of clothing carries a negative social meaning. Especially when pulled over the head of an unidentified black man, the hoodie is strongly associated with wicked criminality in the minds of many Americans: one often sees them in grainy black and white photos of armed assailants on local newscasts, prompting Geraldo Rivera to assert on Fox and Friends on March 23, 2012, that the hoodie was as responsible for Trayvon’s death as Zimmerman, which in turn inspired a “Million Hoodie March” in New York that attracted hundreds of protesters, many of them wearing hoodies.6 Whatever the merits of that assertion, it is hard to deny the association in the popular American imagination between hoodies, young black males, and crime.

Nevertheless, I had no intention of shouting a nappy political statement from the top of my head. Instead, my prodigious performative grew out of my preoccupation with researching and writing this book, which caused me to miss months of trips to my neighborhood barbershop, Hair Architects. As my thesis expanded and grew more radical, so did my nappy hair. Over time, my thesis and hair became increasingly intertwined, like serpentine vines of ivy climbing a redbrick wall. I did not realize how intertwined they had become until I overheard lawyers from LA’s oldest “city” clubs, the California Club and the Jonathan Club, describe my waxing nappiness as “impertinent” and “unprofessional.” These clubs are bastions of corporate and civic power where restraint in bearing, manner, and style are de rigueur and where, following strict dress codes, soberly attired movers and shakers dine and hang out and cut deals. Both clubs barred blacks, Jews, and women from membership until the mid-1980s, when privilege holders were dragged kicking and screaming into the 20th century by lawsuits, threats of lawsuits, a city ordinance, regulatory agencies, and the harsh glare of publicity. What’s more, some of my law students referred to my escalating Afro as “ironic,” in that it made me “look like a criminal” at the same time I teach criminal law. Over time and quite by accident, my hair has grown into a nappy illustration of nonlinguistic political discourse: once dormant, it has been stirred to life by my reflections on the revolutionary power of words and symbols—even ugly epithets and “bad hair”—to pinpoint injustice and bond people together. In this spirit, each morning I activate the performative power in my kinky coils by grabbing a wide-toothed pick by its clenched black fist and sinking its teeth into densely woven mats of hair, followed by choppy outward thrusts in rapid succession that propel spiral shafts vertically into a big, rounded Bat-Signal of solidarity with Black Lives Matter.

—

My father litigated his way out of prison by proving that the District Attorney who prosecuted him deliberately lied to the jury. The DA repeatedly assured them that he had not promised the state’s principal witness (then serving a long sentence) leniency in return for testifying against my dad, when in truth they had struck that very bargain. My professional observations of DAs over the last 25 years have only deepened my distrust. As Professor John Pfaff shows in Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, first among those true causes of racialized mass incarceration is the nearly unchecked power of DAs: more than stiff drug laws, punitive judges, overzealous cops, or private prisons, prosecutors have been the main drivers of the prison boom over the last 30 years. Pfaff found that although crime was steadily declining in the 1990s and 2000s, which one would expect to be accompanied by decreasing incarceration rates, these rates instead soared, for a simple mathematical reason: the probability that a DA would file a felony charge against an arrestee roughly doubled from about one in three to nearly two in three. More than any other single class of elected officials, prosecutors are responsible for quadrupling the number of people incarcerated since the mid-1980s. Excessive blame and punishment has been the stock in trade of prosecutors for many years, at least in part because many DAs have attempted to bolster political careers by racking up convictions.

Therefore, any criminal justice reform, any way out of the carceral state, any way out of the New Jim Crow, any way forward from our current gulag culture, lies in reform at the prosecutorial level. And that will require a new way of thinking. A new theory of justice. It will require Nigga Theory, and it will require progressive prosecutors.

—

Until very recently, I would have scoffed at the notion of a “progressive,” let alone a “radically progressive” or “revolutionary” prosecutor. It would have seemed a ridiculous oxymoron.

But since 2013, voters have elected roughly 30 reform-minded prosecutors, some of them fundamentally reinventing the role of the modern District Attorney. For instance, Larry Krasner, who campaigned on eliminating cash bail, reining in police and prosecutorial misconduct, and ending racialized mass incarceration, won the race for District Attorney of Philadelphia, with 75% of the vote in the general election. In a packed lecture hall in 2018, DA Krasner told my USC law students that ending racialized mass incarceration is “the most important civil rights issue of our time” and, moreover, that the difference between a “traditional” and “progressive” prosecutor is that the latter is a “prosecutor with compassion” and “a public defender with power.” This growing crop of “prosecutors with compassion” and “public defenders with power” has upended my pat, binary way of thinking about the role of the DA. I now recognize the potential of radically progressive DAs to promote deep cuts in racialized mass incarceration. Such prosecutors adopt a fundamentally different moral compass and conception of justice than do traditional “law and order” DAs, the ones whose moral, legal, and political compass sharply distinguishes between victims and perpetrators. They recognize that “hurt people hurt people” and refuse to subordinate the values of restoration, rehabilitation, and redemption to those of retribution, retaliation, and revenge.

I will refer to a truly transformational DA committed to rolling back racialized mass incarceration as a “radically progressive prosecutor” because the simpler “progressive prosecutor” is already becoming a hollow buzzword, fashionable in political circles, but too often used to paper over unprogressive prosecutorial pasts. For instance, in her new book, The Truths We Hold, erstwhile 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris (D–Calif.) touts her record as a “progressive prosecutor,” from the start of her career as a line prosecutor in San Francisco, up through her tenure as California Attorney General. But does a “progressive prosecutor” defend cheating DAs who have been thrown off cases for withholding evidence (Orange County), falsifying evidence (Kern County) or lying under oath, as happened in a Riverside case, Baca v. Adams, involving a corrupt prosecutor chillingly similar to my dad’s DA?7 In Baca, Harris’ office opposed an appeal by a defendant who was convicted after the prosecutor in his case, just like my dad’s DA, lied to the jury about whether an informant received compensation (in the form of leniency) for his testimony. Harris’ office only withdrew its opposition to the defendant’s appeal after a panel of Ninth Circuit judges asked embarrassing questions about why none of the lying DAs were being charged with perjury and threatened to release an opinion that named names if Harris’ office kept up its misguided opposition to the appeal. And does a “progressive prosecutor” fight the release of a wrongfully convicted man, incarcerated based on the testimony of lying cops, as in the case of Daniel Larsen?8 Does a “progressive prosecutor” advocate for and then enforce an anti-truancy policy that arrests and jails mothers of kids who are chronically truant?9 Does a “progressive prosecutor” in 2014 simply laugh in the face of a reporter when asked about her position on marijuana legalization? Does a “progressive prosecutor” refuse to join other states attempting to remove marijuana from the DEA’s list of most dangerous substances? Does she refuse to resist the federal crackdown on weed?10 Of course not! But in every case Kamala Harris did, making her a “progressive prosecutor” only in a Pickwickian sense. To distinguish such so-called progressive prosecutors from truly transformative ones, I will refer to the latter as “radically progressive” or even “revolutionary” prosecutors, labels that incrementalists, centrists, and shape-shifting traditionalists may find harder to misappropriate in furtherance of their political ambitions.

And true criminal-justice reform requires not only radically progressive prosecutors, but equally radical lawmakers, ones with totally different moral compasses than those guiding centrist Democrats like Joe Biden, who, in an address on live television in 1989 excoriated then-president George H.W. Bush for proposing a billion-dollar investment in the War on Drugs that, in Biden’s view, did “not include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, enough prosecutors to convict them, enough judges to sentence them, or enough prison cells to put them away for a long time.” As recently as April 2016, Biden insisted that he was “not at all” ashamed of his central role in passing the draconian 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, an accelerant for mass incarceration better known as the “Clinton crime bill.” Biden, Bill Clinton, and Kamala Harris are vivid reminders that many leading liberals and “progressives” rose to prominence by pushing carceral policies that treated punishing black people as political currency, in the process separating families, destroying communities, and hobbling whole generations.

Radical criminal justice reform will also require the involvement of activists, advocates, journalists, commentators, clergy, public defenders, grassroots political organizations, and radically progressive voters, since they, ultimately, decide the political fate of radically progressive elected officials. Radical reform will require all these agents of change to take on the monumental task of redefining this nation’s values and moral norms in matters of blame and punishment. And the urgent question confronting any and all truly progressive reformers is this: Through what moral, legal, and political lenses do radically progressive people committed to making deep and lasting cuts in racialized mass incarceration look at blame and punishment?

Nigga Theory expounds a radically progressive moral, legal, and political framework for DAs, Public Defenders, lawmakers, activists, and voters to help transform how we think and feel about the disproportionately Black minds, bodies, and souls we currently cage in the name of justice. At the heart of this framework is someone whom liberal critics of mass incarceration too often discount or deny: the violent offender. The widely accepted liberal narrative about racialized mass incarceration, as popularized by Michelle Alexander’s important and influential book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010), argues that racist lawmakers responded to the civil rights era triumphs of Blacks over state-sanctioned racialized segregation—Old Jim Crow—by shifting to another institutional mechanism of racial oppression: the criminal justice system. According to Alexander, the federal government launched the War on Drugs, with “low-level nonviolent drug offenses” driving the explosion in US incarceration rates. “The impact of the drug war has been astounding,” Alexander writes. “In less than 30 years, the US penal population exploded from around 300,000 to more than 2 million, with drug convictions accounting for the majority of the increase.” Recognizing that “violent crime tends to provoke the most visceral and punitive response,” Alexander spells out the most forceful argument of “defenders of mass incarceration” who claim that it is not a form of racial oppression:

They point to violent crime in the African American community as a justification for the staggering number of black men who find themselves behind bars. Black men, they say, have much higher rates of violent crime; that’s why so many of them are locked up.

Her go-to response to those who defend racialized mass incarceration as centered on violent offenders, reiterated in no uncertain terms throughout the book, is that “violent crime is not responsible for mass incarceration.” Warning readers not to be “misled by those who insist that violent crime has driven the rise of this unprecedented system of racial and social control,” Alexander proclaims: “the uncomfortable reality is that arrests and convictions for drug offenses—not violent crime—have propelled mass incarceration.”11

The clear implication, of course, is that the “uncomfortable reality” of racialized mass incarceration might not be so uncomfortable if it afflicted mostly violent offenders rather than nonviolent drug offenders; a core premise of this book is that it should be an intolerably “uncomfortable reality” in relation to both violent and nonviolent offenders. This deep conventional moral distinction between violent and nonviolent offenders drives the liberal New Jim Crow narrative, centering it on the latter and repeatedly making their draconian treatment the touchstone of injustice. As recently as 2015, President Obama publicly propagated this factual cornerstone of the narrative: “Over the last few decades, we’ve also locked up more and more nonviolent drug offenders than ever before, for longer than ever before, and that is the real reason our prison population is so high.” It’s infinitely easier to carry a brief for nonviolent than violent offenders in the court of public opinion. Accordingly, Alexander places great rhetorical weight on the distinction, declaring in one passage that “[w]e ought never excuse violence,” while urging in another that we ought to excuse low-level nonviolent wrongdoing because “all people make mistakes,” “all of us are sinners,” “all of us are criminals,” “all of us violate the law at some point in our lives,” and “most of us break the law not once but repeatedly throughout our lives.” For instance, “most Americans violate drug laws in their lifetime,” she observes, and “[y]et there are people in the United States serving life sentences for first-time drug offenses,” she laments—lost generations of Blacks “rounded up for crimes that go ignored on the other side of town.”12

The rhetorical force of this language rests entirely on the factual assumption that we are talking about low-level, nonviolent offenses, for from the standpoint of prevailing values and moral norms it sounds preposterous to say all of us are violent criminals or all of us violate laws against robbery, rape, homicide, and assault at some point in our lives. And of course violent crimes are not ignored in privileged predominantly white communities, so it’s hard to say that violent offenders in black neighborhoods are being rounded up for, say, murders that go ignored on the other side of town. If anything, far too few murders and other violent crimes in the black community are solved, prompting a community organization like Baltimore’s Mothers of Murdered Sons and Daughters to sponsor billboards calling on the mayor to “STOP POT ARRESTS. SOLVE MURDERS INSTEAD.” But this rhetoric invites a political distinction in criminal matters between an “us” of low-level, nonviolent, eminently excusable wrongdoers and a “them” of violent ones, the ones who “jeopardize the safety and security of others” and whose violence “we ought never excuse.”13 It invites a politics of compassion for ordinary human frailty, as long as that frailty does not express itself in violence. And most importantly, it promises that deep cuts in racialized mass incarceration can be accomplished on the cheap, without radically challenging our “comfortable” moral frameworks or political identities; all that it asks for is sympathy and leniency for low-level nonviolent offenders who deep down are morally indistinguishable from the rest of us.

This is why facts matter: different factual realities demand different moral lenses and different us-them politics. Factually, the liberal New Jim Crow narrative could hardly be more wrong and misguided, rendering its underlying moral compass and politics profoundly regressive and counterproductive for anyone seeking deep and lasting cuts in racialized mass incarceration. As Pfaff points out in Locked In, “only about 16% of state prisoners are serving time on drug charges—and very few of them, perhaps only around five or six percent of that group, are both low level and nonviolent.” “At the same time,” he continues, “more than half of all people in state prisons have been convicted of a violent crime.” Because the vast majority (87%) of US inmates are held in state prisons, most people in US prisons simply are not there for low-level nonviolent drug offenses.14 The problem with telling the public that racialized mass incarceration boils down to low-level, nonviolent drug offenders (perhaps who simply need to be diverted into non-carceral programs) is that this false factual account lulls lawmakers and concerned citizens into the comfortable but counterproductive fantasy that deep cuts in the prison population can be achieved by targeting a lot of relatively sympathetic prisoners. Nevertheless, this false narrative has become an ingrained article of faith for many progressives.

The New Jim Crow deserves great credit for helping many Americans—especially but not exclusively white liberals—begin to think about racialized mass incarceration as a civil rights crisis rather than simply a “law and order” problem resulting from the bad choices of bad people. When The New Jim Crow was published in 2010, the debate over issues like affirmative action in higher education was consuming much of the time, attention, and other resources of the civil rights community, and Alexander’s book, more than any other, helped establish racialized mass incarceration as the main battlefront in US race relations, which is why the book became, in the words of one commentator, “the bible of a social movement”—truly a monumental achievement. But because of fatal flaws in its factual account, moral compass, and politics, the liberal New Jim Crow narrative now actually hurts more people locked in American prisons than it helps.

For instance, in a 2016 Vox poll, more than 2,000 registered voters overestimated how many people are in prison for nonviolent drug offenses. A total of 61% of respondents said that half of all prisoners in the US are incarcerated for drug offenses. In fact, most of the growth in state prison populations was driven by sentences for violent crimes like murder, assault, robbery, and rape.15 Such misconceptions about the makeup of prison populations may lead voters and policymakers who want deep cuts in mass incarceration to think they can make a real difference simply by reducing prison time for nonviolent offenders: 78% of respondents said that “people who committed a nonviolent crime and have a low risk of committing another crime” should be let out of prison earlier, but only 29% (including only 42% of liberals) said they supported reducing prison time for “people who committed a violent crime and have a low risk of committing another crime.” No majority of any race, religion, ideology, political party, or any other category evaluated by pollsters supported reducing prison sentences for violent criminals with “a low risk of committing another crime.” Further, about 55% of voters said that one acceptable reason to reduce sentences for nonviolent drug offenders is “to keep room for violent offenders in prisons.” In other words, many viewed making cuts in the incarceration of nonviolent drug offenders as desirable, in part, because such cuts make it possible for the state to lock up more violent offenders. The much-heralded bipartisan First Step Act of December 2018 (FSA) reinforced this logic by providing programming and early release measures targeting the “non, non, nons”—those convicted of nonviolent, nonserious, and nonsexual crimes. FSA critics worried that by sharply distinguishing nons from other criminals, the legislation might actually bolster the carceral state by improving the conditions of confinement for the few—and thus defusing criticisms of prison conditions—at the expense of the many.

By distinguishing and distancing nonviolent from violent criminals and focusing on low-level nonviolent drug offenders, the liberal New Jim Crow narrative promotes sentence reductions for that relatively small subdivision of the prison population while doing little to reduce numbers or improve the fate of the many more violent offenders left behind. Ironically, Alexander criticizes traditional proponents of respectability politics for failing to prioritize the needs of the most disadvantaged blacks and for aggressively pursuing policy reforms that would harm them, yet her own rhetoric fails to prioritize the needs of the most maligned and marginalized criminals, the violent ones. It affords inclusion and acceptance for a few but guarantees exclusion for most. Justice, leniency, and compassion for the majority of people behind bars cannot be purchased on the cheap—it will require deep and uncomfortable changes in our collective moral compass and us-them politics. Traditional respectability politics distinguished itself from all black lawbreakers, whereas the liberal New Jim Crow narrative’s refined brand of respectability politics distances itself only from the violent ones. Under the old, crude respectability politics, all black criminals were “damaged goods” as representative victims around whom to rally in the name of racial injustice, but under the liberal New Jim Crow narrative’s more refined version, only violent black criminals are “damaged goods,” and the representative victims of racialized mass incarceration are the non-non-nons. In crude respectability politics, no blacks with criminal records are “seen as attractive plaintiffs for civil rights litigation or good ‘poster boys’ for media advocacy”16; in refined New Jim Crow respectability politics, none with violent criminal records are.

The New Jim Crow analogy must reckon with a wide moral gulf—a yawning moral chasm in politics and everyday morality—between the innocent victims of state-sanctioned segregation and the more blameworthy, violent victims of racialized mass incarceration. Through respectability-tinted moral lenses, victims of traditional Jim Crow were the morally innocent Negroes—exemplified by iconic leaders like Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Rosa Parks—subjected to state-sanctioned social oppression for being black. Even if some of these civil rights era victims of social oppression ended up in mug shots or jail cells for protesting their subjugation, typically it was for civil disobedience in the name of morally praiseworthy resistance. By stark contrast, most blacks who are subjected to state-sanctioned racialized mass incarceration are not morally innocent. Most are violent or serious offenders who made criminal choices to commit crimes of moral turpitude, often preying on the most vulnerable members of their own already marginalized communities. The state blames and punishes such offenders on the basis of what they did, not simply for who they are, making them problematic as “attractive plaintiffs for civil rights litigation.” Viewed through respectability-politics-tinted moral lenses, the Old Jim Crow oppressed morally innocent Negroes, making them true victims of racial oppression, while the so-called New Jim Crow oppresses mostly serious black wrongdoers, making them authors of their own plights, not true victims.

Nigga Theory says, let’s see things clearly.

Good Negro lenses reinforce the common but regressive distinction between social oppression and self-destruction, that is, between the kind of racial injustice at the heart of the Old Jim Crow (innocent Blacks suffering racial oppression for which America clearly can be held collectively accountable) and the kind of racial injustice really at the heart of the New Jim Crow (culpable Blacks, disproportionately trapped in criminogenic social conditions, who consequently disproportionately make bad choices). These bad choices might be seen to break the causal chain between racial oppression in America and racialized mass incarceration, thus absolving America of accountability for the foreseeable and violent criminal consequences of its unjust basic structure. Through such distorting lenses, there is no moral equivalence between social oppression and self-destruction—that is, between Medgar, Martin, Rosa and a murderer or an armed robber serving a life sentence. Nigga Theory begs to differ.

Death penalty cases provide another illustration of how the lenses of Nigga Theory differ from approaches to blame and punishment that seek to garner greater support and leniency for wrongdoers solely by focusing attention on those who are more appealing when looked at through conventional moral lenses. The great rhetorical force of DNA exonerations—the possibility of executing the innocent—has played a big role in the decline in public support for the death penalty over the last 20 years. For instance, Republican Governor George Ryan of Illinois, once a supporter of capital punishment, declared a moratorium on executions in the state, then granted clemency to all 171 inmates on death row, after 13 Illinois inmates who had been convicted and condemned to death were exonerated, some just hours before their scheduled lethal injections. “Until I can be sure that everyone sentenced to death in Illinois is truly guilty,” said Ryan, “no man or woman [facing execution] will meet that fate.”

But Nigga Theory rests on the premise that the greatest driver of mass incarceration and threat to racial justice in criminal matters is not false convictions of factually innocent people or excessive sentences for low-level nonviolent offenders, but rather the disproportionate blame and punishment of guilty black people who have committed serious or violent offenses. Just as deep cuts in racialized mass incarceration cannot come simply from diversion programs for low-level nonviolent drug offenders, deep racial injustices in capital punishment cannot be remedied simply through the protection of innocent people from wrongful convictions and executions. In fact, just as focusing decarceration efforts on low-level nonviolent drug offenders perversely deepens the plight of most American prisoners, focusing anti-death penalty efforts on avoiding the execution of innocent people can deepen the plight of most death row inmates because the factual guilt of most may not be in any real doubt. My dad was given a life sentence despite his factual innocence, but he’d be the first to tell you that the factually guilty far outnumber the factually innocent behind bars. Certainly Stanley “Tookie” Williams, whose execution by the state of California I fought and then wrote a play about—called Race, Rap, and Redemption—was factually guilty of committing multiple premeditated murders. Innocent black people disproportionately condemned to death can be readily recognized as victims of social oppression, whereas guilty wrongdoers are routinely viewed as authors of their own demise, echoing the “social oppression of innocent Negroes” vs. “self-destruction of guilty niggas” dichotomy embraced by proponents of respectability politics and refuted throughout this book.

By keeping attention trained on serious, violent, and guilty wrongdoers, Nigga Theory makes clear its rejection of even an error-free death penalty. Even if we achieve practical certainty about a person’s factual guilt, and thus save all the falsely accused innocent lives that can be saved by wringing that kind of error out of the criminal justice system, the determination that a factually guilty person is deathworthy is profoundly and directly a moral judgment about their subjective culpability and just deserts, and this moral judgment can be just as rife with error, bias, and arbitrariness as factual, killer-identification “whodunit” judgments. The excessive blame and punishment of guilty black offenders, especially the violent and serious ones who most inflame the urge for retaliation and revenge, is a much more pervasive and pernicious problem, running throughout every phase of the criminal justice system, than the problem of wrongful convictions or executions of innocent blacks (which is not meant, at all, to minimize the grave seriousness of the latter).

In order to break out of the trap of mass incarceration, we, as a society, need to rethink the basic processes of our criminal justice system through the moral and legal lenses of Nigga Theory, lenses that expose a system corrupted by racism of an absolutely mundane, everyday kind, and corrupted at every level:

At the level of arrest.

At the level of charging.

At the level of factfinding.

At the level of trial.

At the level of sentencing.

It is the project of Nigga Theory to interrogate the system at every one of these levels in order to expose where racial bias lives in the criminal law and adjudication of just deserts.

—

Harvard University law professor Randall Kennedy, in Race, Crime, and the Law, urged morally innocent and law-abiding “good Negroes” to distinguish and distance themselves from morally culpable and criminal “bad Negroes”—a classic instance of the politics of respectability. This same wicked-worthy moral dichotomy runs through popular culture, figuring centrally in a famous standup routine by iconic black comedian Chris Rock (Bring the Pain, 1996), in which he paces the stage and declares that “it’s like there’s a civil war going on in black America” between respectable, law-abiding, lovable “black people” and disreputable, criminal, blameworthy “niggas.” He liberally sprinkles his long and sneering rant against morally condemnable black wrongdoers with the trenchant punchline: “I love Black People, but I hate niggas.” As James Boyd White points out, jokes, like all texts, are invitations to share the speaker’s response to the world, an invitation which we accept through our laughter,17 and implicit in Rock’s joke is a political invitation to sharply distinguish between a law-abiding and morally upright “us” and a criminally blameworthy “them.” It’s an invitation to niggerize black wrongdoers, which black audiences in packed auditoriums merrily accepted through peals of laughter and a chorus of “amens,” “uh-huhs,” and “preach!” No utterance in the English language more forcefully distinguishes and distances a respectable “us” from a contemptible “them” than the N-word, no word drives a deeper moral and political wedge between the worthy and the wicked, no epithet more utterly otherizes its referent.

Nigga Theory instead appropriates the N-word’s unparaphrasable power, the power it has to morally condemn and otherize criminals, especially violent black ones, and instead uses it as a term of art in a radically progressive theory of blame and punishment, a theory crafted to shake the foundations of all our conventional condemnations of criminals, including the most violent and forsaken black ones. I could adopt professor Kennedy’s more genteel language and call this brand of Critical Race Theory “Bad Negro Theory,” but “Bad Negro” doesn’t otherize wrongdoers as forcefully or condemn them as contemptuously as the N-word. In the hands of black speakers and writers, the N-word can be a jagged-edged assault weapon that draws blood or a healing scalpel that sutures the places where blood flows. I reclaim this reclaimed word by both denying any substantive moral basis for using it to divide the worthy from the wicked and, at the same time, embracing its healing, bonding, unifying force.

This book also uses the racially charged N-word to keep race itself front and center in the discussion of mass incarceration, and to pointedly reject the canard pushed by leftists, liberals, and conservatives that class trumps race in our criminal justice system. Yet more proof that race takes priority came across my timeline as I was writing this Introduction: a viral video, in which a phalanx of cops physically assaults a black student at Columbia University because he looked like he did not belong in those hallowed halls of ivy. I’ve had many similar experiences.

What do they call a black man getting a Columbia degree?

A nigga.

What do they call one who has already earned said degree?

A nigga.

What do they call one like me who’s a chaired law professor with degrees from Harvard and Berkeley?

A nigga.

Word to black America—you might earn fancy degrees and make big cash, but you cannot cash in your face, for the face of crime in the eyes of law enforcement and civilians alike is black. As Jay-Z puts it in “The Story of O.J.”:

Light nigga, dark nigga, faux nigga, real nigga

Rich nigga, poor nigga, house nigga, field nigga

Still nigga, still nigga

To signal its sharp departure in style and substance from conventional morality and respectability politics, as well as to keep the independent importance of race at all times front and center, the central argument of this book, Nigga Theory, adopts a profane, transgressive, disruptive, and disreputable N-word-laden rhetoric steeped in irony, inversion, and oppositional black art of the kind crafted by politically conscious N-word virtuosos like Pac, Nas, Cube, and Hov.

I understand readers who nevertheless inwardly recoil at every utterance of the ugly epithet. I respect the N-word abolitionists who have protested some of my N-word-laden performances, exhibits, and speeches because, in their view, the word’s racist roots make it inherently hateful and hence make some of my celebrations of its “virtues” misguided hate speech. I once shared that view myself. Like many others, I viewed the N-word as a variety of what the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) calls “fighting words,” words that “by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.”18 I quoted that language to Santa Monica police officers in my explanation of why a white male store clerk’s application of the N-word to me during a verbal exchange provoked a reflexive backhand. I avoided charges and a mug shot, but it was not my proudest moment. And still, despite my longstanding visceral distaste for the violent insult, I have become convinced—by many radically progressive black writers, performing artists, poets, philosophers, and commentators—of the unique rhetorical efficacy of the N-word. When black folk use it with care and precision to disrupt and displace dehumanizing discourses about them, they ultimately enact their own transgressive, transformational word work.

—

Nigga Theory refuses to reduce race to class (Rich nigga, poor nigga ... still nigga), while some progressive narratives carelessly conflate the two. “All of Us or None” is a terrific grassroots organization of formerly incarcerated men and women whose name is the perfect slogan for a politics that centers incarcerated violent black offenders and refuses to leave them behind; but for Michelle Alexander, its importance lies in its ability to encourage political solidarity between blacks and poor and working-class whites.19 For many on the left, the election of Donald Trump was a confirmation of the standard liberal account of why poor and working-class whites support racially illiberal politicians and policies. Economically distressed working-class white people, anxious about trade and lost manufacturing jobs and the decline in their overall economic level, especially after the 2008 Great Recession, felt financially “left behind” and so sought solace in the catharsis provided by hating and hurting Blacks, Latinos, Muslims, foreigners, in a word, others, and thus cast ballots for Trump to shore up their social status and threatened sense of social superiority, to give themselves a form of cultural and psychological compensation, a psychic benefit, that W.E.B. Du Bois calls the “public and psychological wage” of whiteness—an anodyne for their economic pain and suffering and anxiety.

Alexander agrees; she claims that conservatives garnered the votes they needed to create racialized mass incarceration by “appealing to the racism and vulnerability of lower class whites, a group of people who are understandably eager to ensure that they never find themselves trapped at the bottom of the American totem pole.”20 Thanks to the special susceptibility of poor and working-class whites to racist demagoguery, according to Alexander “a new system of racialized social control [namely, the New Jim Crow] was created by exploiting the vulnerabilities and racial resentments of poor and working-class whites.”21 In his polemic about the dangers of “identity politics,” Mark Lilla makes a similar point:

Marxists are much more on-point here…people who might be on the edge are drawn to racist rhetoric and anti-immigrant rhetoric because they’ve been economically disenfranchised, and so they look for a scapegoat, and so the real problems are economic.22

Even conservatives got in on the-bashing-the-white-working-class act, in Kevin D. Williamson’s National Review article about the allegedly strong support for Trump among working-class whites. He states, “The white American underclass is in thrall to a vicious, selfish culture whose main products are misery and used heroin needles. Donald Trump’s speeches make them feel good. So does OxyContin.” The conservative commentator continues: “the truth about these dysfunctional downscale communities, is that they deserve to die.”23 Marxists, liberals, and conservatives found common ground after Trump’s election in stereotyping and scapegoating working-class whites as broke and bitter and therefore especially prone to rabid irrationality.

This claim is deeply classist claptrap. It impugns the character of honest hardworking white people struggling to scratch out a living in America’s casino economy and implies that economic suffering somehow robs white people of moral agency, clouds their conscience, makes them especially susceptible to ethno-nationalist demagoguery, and impels them to make racially illiberal choices. Of course many white working-class people voted for Trump, but even more middle-class whites did. The insecurity they felt was not primarily economic. The 2016 election of Donald Trump provides a rare opportunity to test and debunk the class-anxiety canard. On the campaign trail, Mr. Trump went beyond racially charged dog whistles and code words and unapologetically wore his racism on his sleeve, rising to political prominence by pushing “birtherism,” a conspiracy theory that the country’s first black president was not an American citizen.24 He declared in his Presidential Announcement Speech that undocumented immigrants from Mexico were “bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” During his campaign, he tweeted an image of a masked, dark-skinned man with a handgun alongside a set of points about deaths in 2015, including the wildly false and inflammatory claim that 81% of whites are killed by blacks (in reality roughly 82% of white murder victims are killed by whites each year). He vowed to ban Muslims from entering the United States while signaling potential support for a Muslim registry (raising the specter of Manzanar-style internment camps). He asserted that a Latino US District Judge, Gonzalo Curiel, presiding over civil fraud lawsuits against Trump University, could not be impartial because he was “of Mexican heritage.” Amid protests over fatal police shootings of unarmed black people, he railed against a “war on police” and promised to institute a national “stop and frisk” policy that had already been struck down as unconstitutionally discriminatory in his own New York.25

Poor and working-class whites, the ones suffering the greatest economic distress in the four years leading up to Trump’s election, were not more susceptible to his brand of white identity politics than better-off whites, and indeed, it was well-off whites who were more likely to support Trump. Research shows that even whites who voted for Obama in 2012 and switched to Trump in 2016 were motivated to do so by racism, not economic anxiety, and that racism can make people anxious about the economy rather than the other way around. White identity politics carried Trump to the White House, not economic anxiety. Simply put, race trumped class in 2016. White nationalism trounced economic equity. Racism was a much more powerful force in the election of Donald Trump than white working-class economic disenfranchisement.

Facts matter in the fight against racial oppression in America, including facts about voter motivations. Those who see economic and financial insecurity as the root cause of Trumpism and other kinds of racially illiberal demagoguery will seek to curb racism through policies that strengthen the social safety net. But universal basic income, “Medicare for all,” or other redistributionist economic policies, although they deserve our support because they’re morally right and economically feasible, will not win over Trump voters—these voters are more fearful of losing their dominant status as white people within a demographically diverse and ever-evolving nation than they are about economic issues. In fact, the studies show that Trump’s supporters—again, most of whom were not poor or working-class—largely oppose policies that would reduce the economic distress of poor and working-class whites because, thanks to a decades-long campaign to destroy support for the safety net by racializing government programs with tendentious tropes of Cadillac-driving black welfare queens and the like, they view such policies as handouts for Blacks and other people of color. Deep-seated psychological resentment and racial anxiety rooted in a sense of group status threat are uniquely, independently, and irreducibly racial problems that demand racial solutions.

All too often, liberals pay lip service to the role of group status in the formation of political preferences, and yet they consistently lowball just how psychologically valuable it is to see one’s self as part of the dominant social group—they too often grossly underestimate the value of what Du Bois identified as the psychic boon of whiteness. They believe that people’s economic self-interest must logically take priority over other concerns. Alexander, for instance, argues that poor and working-class whites were persuaded by elites and capitalists to prioritize their racial status interests over their common economic interests with Blacks, “resulting in the emergence of new caste systems that only marginally benefit whites but were devastating for African Americans.”26 (Emphasis added.) But the data will show that the symbolic, psychic boon of whiteness—whites’ sense of dominance over America’s social and political priorities—is not some sop that “only marginally benefits whites.” As University of Pennsylvania political scientist Diana C. Mutz points out, “what we know about American voters is that symbolic appeals matter a great deal.”27 Psychologically and emotionally, seeing one’s self as part of a dominant group can feel real good.

There is nothing “illogical” about people finding symbolic considerations more urgent and compelling than material ones. It is not “illogical” to weigh substantial psychic satisfactions against significant economic frustrations and conclude that the former outweigh the latter. Taking pride in one’s social identity, reveling in belonging to a certain social group—even an historically subjugated one—can bring as much psychic satisfaction to members of that social entity as great material compensation. As Maya Angelou puts it in “Still I Rise,” despite being trod in the dirt, “I walk like I’ve got oil wells/ Pumping in my living room.” It’s dangerous for a racially oppressed people in America to ever underestimate the psychic boon for white people of belonging to a racial group that has enjoyed social dominance in this nation since its inception, a feeling for many that is emotionally equivalent to (Angelou again) having gold mines “diggin’ in [their] own backyard.” To grasp the nuances of this nation’s primordial divide over race, we must never downplay its irreducible centrality and independent potency.

Of course, both race and class matter, and both are central to a radically progressive racial justice agenda, for civil rights without economic redistribution will leave far too many truly disadvantaged folks behind. But it’s a grave mistake to view class-based policies as likely to reduce the racial resentments or status anxieties of white voters. Elected officials who embrace the misguided “economic anxiety” narrative in hopes of reducing the appeal of racist demagoguery may pursue policies that will do little to assuage the racial anxieties of whites who cast their 2016 ballot out of deep-seated fear that they were slowly losing their social standing in America and that Trump was the best candidate to reinforce this nation’s racist hierarchy. When these voters hear about racialized mass incarceration or rampant police misconduct or “inclusion, diversity, and equity” in schools and workplaces, they’re listening with ears attuned to demographic trends, cultural shifts, and anxiety about their own future. Unlike economic threats, status threats—anxieties about power, identity, and group superiority—strike at the heart of who and what one is, and what it means to identify as a white man, woman, boy, or girl in America. It may prove hard to economically “bribe” fearful whites to accept a somewhat higher standard of living in exchange for what many view as existential annihilation or, in the pungent phrasing of some ethno-nationalist scaremongers, “white genocide.”

The economic anxiety explanation for Trumpism and white identity politics belongs to the category of what Paul Krugman calls zombie ideas—arguments that have been proven wrong, should be dead, but nonetheless “shamble relentlessly forward” because they serve a political purpose.28 For some, the economic anxiety narrative serves to promote a redistributionist economic policy. For others, the economic distress excuse props up the legitimacy and moral authority of American democracy. So pundits and politicians persist in trotting out the brain-eating economic anxiety theory despite the slew of zombie-slaying studies that offer plain conclusions: helping white voters feel less economic vulnerability does not automatically make them less prone to support racist policies and politicians.

—

The liberal New Jim Crow narrative also robs black folk of agency, treating racialized mass incarceration as an affliction foisted upon the black community by external actors rather than as what it actually is: a bottom-up phenomenon driven by moral condemnations of black wrongdoers by both nonblack and black citizens and elected officials. Think back to the height of hysteria about the crack plague and street crime, during the period when Blacks were being warehoused in prison blocks and jail cells at precipitously rising rates. Most members of the Congressional Black Caucus, responding to their constituents, voted in favor of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which fueled the War on Drugs by establishing for the first time mandatory minimum sentences for specified quantities of cocaine as well as a 100-to-1 sentencing disparity between crack (more associated with black users) and powder (more associated with white users) cocaine. Seven years later, a 1993 Gallup Poll found 82% of the Blacks surveyed believed that the courts in their area did not treat criminals harshly enough; 75% favored putting more police on the streets to reduce crime; and 68% supported building more prisons so that longer sentences could be given.29 Widespread support for “get tough” crime policies among black citizens and politicians as prison populations exploded undermines the liberal New Jim Crow narrative’s core claim. Black folk, despite bearing the brunt of mass incarceration, fueled our own hyper-incarceration by looking at criminal justice matters through conventional moral lenses tinted with our own respectability politics.

As Alexander notes, “violent crime tends to provoke the most visceral and punitive response” in concerned black citizens, who supported more prisons and longer sentences through these years.30 This cannot be argued away, as Alexander tries to, by distinguishing between “support for” and “complicity with” racialized mass incarceration,31 a distinction that dissolves under mild interrogation. Nigga Theory assumes that “law and order” black folk engage in meaningful moral reflection and make nuanced moral judgments, and are capable of critical self-reflection and self-revision, and thus open to persuasion, as people ready to think through what approaches to blame and punishment best serve the black community’s interest in equal justice for all. Widespread moral condemnations of black criminals—especially violent ones like Willie Horton, the dark-skinned convicted murderer featured in an infamous 1988 presidential campaign ad who escaped while on work furlough and then raped a white Maryland woman and bound and stabbed her boyfriend—percolated into the policies and practices of nonblack and black “tough on crime” DAs, police chiefs, politicians, and other “official” drivers of racialized mass incarceration. As I’ve been saying in print and in person for over 20 years, prevailing values and moral norms about blame and punishment, especially the blame and punishment of violent or serious black offenders, were—and are—the taproot of racialized mass incarceration. Black folk, despite bearing the brunt of such incarceration, unwittingly became accomplices of the carceral state and complicit in our own hyper-incarceration by adopting the same regressive moral framework in criminal matters. In addressing the future, any theory needs to address black as well as white attitudes and understandings.

—

To help humanize violent black offenders and keep them centered throughout our discussion, this book draws on one of America’s most powerful, provocative, transgressive, and disreputable N-word-laden forms of political communication and art: Gangsta Rap, a particular bête noire of proponents of respectability politics, who heap scorn on the genre for the violence, misogyny, homophobia, and materialism commonly associated with it (Alexander, for instance, refers to gangsta rappers as “black minstrels”32). That there are mindless mercenaries, misogynists, and homophobes in gangsta rap cannot be denied (stand up Rick Ross et al.). But what also cannot be denied by anyone who actually listens to the music is the way some of its most popular and accomplished performers—Pac, Nas, Hov, and Ice Cube—spit lyrics laced with political commentary and invitations to sympathetically identify with black criminals, including violent black hustlers and gangbangers. Rather than passively accept being reduced to objects of derision and butts of jokes, these transgressive griots grabbed mics and dropped multiplatinum albums that penetrated pop culture with their own violent-black-offender narrative, the “narrative of a Nigga,” if you will, complete with that narrative’s own moral and political lenses. In style (lyrics liberally sprinkled with the disreputable N-word and other profane utterances), these songs rejected respectability politics; in substance, these performers rejected the “lovable Black People”/“condemnable Nigga” moral dichotomy. It’s wrong to tar reflective and critical gansta rappers with the same brush as shallow and rudderless hacks.

In 2007, at USC’s Bovard Auditorium before over 1,000 students, faculty, and alumni, Joanne Morris produced a play I wrote called Race, Rap, and Redemption, which was designed to explore issues of racial and social justice, oppression, unity, theology, and redemption through rap and hip-hop music, dance, song, and poetry. I will discuss this example of what Clifford Geertz calls “metaphysical theater” in some detail below, but for now will just mention that it deployed gansta rap in support of an iconic violent black criminal—a death row inmate named Stanley “Tookie” Williams, a convicted murderer and one of the people who helped flood the streets of our own South Central neighborhoods with crack and violence, a co-founder of the notorious street gang called the Crips. Because USC is located in South Central Los Angeles, crime is of more than academic interest to our scholarly community—on a first-hand basis, we pay the price of proximity to poor and crime-ridden neighborhoods and must continuously strike a balance between fear and compassion. Just before the event, Mr. Williams had been executed by the state of California. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger had denied his 11th-hour petition for a reprieve. Incorporated into our reflections on whether we should “pour liquor for Tookie,” (that is, express solidarity with him in the form of a libations ritual) were live performances of gangsta rap and gangsta rap-inspired song, dance, drama, cinema, sermon, and spoken word. As the video of the event shows,33 on that night most of the Trojan community in attendance accepted the invitation to bond with even the “wickedest” black criminal by rising to their feet in empathy for and solidarity with other Tookies still sitting on death row.

Transgressive words and symbols and performances can change hearts and minds, but they can also cost those who take part in them their personal freedom or professional ambitions when, in the eyes of authorities or higher ups, edgy utterances cross from the cutting edge to the bleeding edge. For instance, my play included live performances by Ice Cube, whom police have repeatedly arrested for going on stage and uttering these provocative but unmistakably political lyrics:

Fuck tha police, coming straight from the underground

A young nigga got it bad ‘cause I’m brown

And not the other color, so police think

They have the authority to kill a minority

Cube also performed that anthem—N-word-laden, profanely oppositional—in my Bovard production, triggering severe negative consequences for the interim law school dean, whose programming support made Cube’s defiant performance possible. That dean suffered the wrath of our then-president and then-provost for aiding and abetting such an inflammatory performance in what they called “the tinderbox ready to ignite that is South Central L.A.”34 Nigga Theory traffics in transgressive utterances precisely because it is a way to examine the relationship between freedom of expression, academic freedom, transgressive art, unsayable words, words that wound, hate speech, racial justice, and social change. Nigga Theory necessarily stands against hate speech codes and against finding secret satisfaction in seeing someone “punch a Nazi” on viral videos, not because I have any particular sympathy for racists or Nazis, but because down that road lies destruction for black dissidents and dissenters whose oppositional words and symbols offend people with privilege and power.

—

Racialized mass incarceration has been a river fed by many streams, but by far its biggest tributaries have been the moral, legal, and political lenses through which ordinary people both inside and outside the black community look at black criminals, especially serious or violent ones. Accordingly, Nigga Theory weaves together critical reflections on morality, law, and language in the form of political communication.

It’s the absence of doubt—the moral certainty that one is righteously doing the right thing—that deliberately kills people, by strapping on a bomb and walking into a crowd of tourists, for instance, or by strapping down a man in a chair and injecting, gassing, shocking, or shooting him to death. Nigga Theory argues for less certainty and for more epistemic humility in our moral discourse, and criminal condemnations of black wrongdoers on five different, interlocking levels.

First, drawing on Tommie Shelby’s Dark Ghettos: Injustice, Dissent, and Reform and its Rawlsian critique of America’s unjust basic social structure35 (John Rawls insisted on reciprocity in his theory of justice), Nigga Theory asks whether or not denizens of dark ghettos owe a duty to obey the laws of an intolerably unjust social system. Those who justify punishing desperately poor black criminals on “paying a debt to society” grounds assume a social system in which the burdens and benefits of social cooperation are fairly (or at least not intolerably unfairly) distributed, and that laws benefit everyone. So, as a kind of debt for the benefits gained, everybody owes obedience to those laws; someone who breaks the law owes something to those who do not, because he has acquired an unfair advantage. Punishing him takes from him what he owes, exacts that debt, and thereby restores the equilibrium of benefits and burdens. Nigga Theory debunks this “Gentlemen’s Club” picture of the relation between black folk and society, exposing the emptiness of the claim that the state—as The People’s representative in criminal prosecutions—is morally justified in punishing truly disadvantaged black criminals to make them pay their “debt” to society.

Second, even if, under a Rawlsian analysis, the state retains the moral right to punish morally condemnable (albeit unjustly oppressed) black offenders, anti-black bias—buried, or not, in the cognitive unconscious of ordinary judges and jurors—undermines the reliability, impartiality, and fairness of such moral condemnations.

Third, the moral condemnations of any wrongdoer of any race cannot be trusted at a philosophical level because the phenomenon of moral luck—the radically counterintuitive findings of moral philosophers like Thomas Nagel and Bernard Williams that all praise, blame, and moral responsibility hinge on fortuity—undermines the rationality and legitimacy of all moral condemnation.36 The “self” is a tissue of contingencies and one’s moral status a crapshoot, and this provides a fresh framework and vocabulary for thinking about ancient questions of free will and blameworthiness.

Fourth, Nigga Theory considers the moral responsibility of the United States itself (again, We the People) for the criminal behavior of many violent black wrongdoers. It identifies two grounds for such responsibility: the general criminogenic social conditions (like extreme social disadvantage that the state fosters or lets fester), and federal and state policies that helped jumpstart the crack plague of the 1980s and 1990s. Federal and state governments bear major responsibility for crime caused by chronic unemployment, grinding poverty, crumbling schools, inadequate health care, food and shelter insecurity, hunger and homelessness, and the foreseeable carceral consequences. A violent offender’s bad choice or criminal intent does not break the causal chain between racial oppression and criminal wrongdoing in black communities—it is a foreseeable link in that causal chain for which those who maintain our unjust social order bear responsibility.

Fifth, according to conventional legal theory, violent black offenders—black murderers, for instance—are merely “found” or discovered during the “fact-finding” process of a criminal trial by jurors acting as fact “finders.” In reality, black murderers are not “found” like discoverable facts of nature, they are socially constructed, manufactured, minted, if you will, in DA offices, on benches, and in jury boxes by prosecutors, judges, and jurors. To expose where bias lives in the substantive criminal law and its processes, and how judges and juries socially construct black murderers, Nigga Theory refutes and remodels criminal law’s prevailing paradigm of mens rea (criminal intent), the law’s ancient and foundational requirement of moral blameworthiness. Under the mens rea requirement, a killing without malice is manslaughter rather than murder; a criminal killing with malice is murder. But in most criminal trials, a decision needs to be made by the jury about the existence of malice. Because ordinary people unconsciously and routinely make biased moral judgments of black wrongdoers, as studies have shown, they more readily find that a violent black offender acted with murderous mens rea than a similarly situated violent white one. Nigga Theory will cast serious doubt on the reliability, objectivity, and trustworthiness of criminal conviction as a test of the most morally blameworthy Blacks.

—