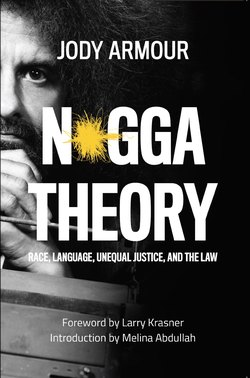

Читать книгу N*gga Theory - Jody David Armour - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

by Melina Abdullah

I was born in East Oakland … a city defined by the kind of lumpen radicalism that gave birth to the Black Panther Party, neighborhoods teeming with Texas- and Louisiana-born grandparents on front porches, teenagers on corners, dirty-faced kids hopping backyard fences to steal neighbors’ plums. Every Friday night, my Beaumont-born-elementary-school-teacher-community-other-mother-brilliant-single-mama would load my brother and me into her faded Volvo station wagon to head to Flint’s Barbeque on San Pablo Ave., one of the most formidable “ho-strolls” on the planet. In the 1970s, “ladies of the night” dressed in shiny magenta pants, tube tops, rhinestone-studded heels, and extra-long painted nails, with matching lip-gloss … the epitome of glamour. My face pressed against the car glass, I longed to be like them. Beautiful and free. Through the cracked window, I heard the accompanying sounds: loud-talking, cussing, and laughter. The “n-word” abounded—dripping from the lips of men dressed in flashy suits, snakeskin shoes, and matching hats … an extended “aaahhhhh” at the end, n**** danced to the rhythm of the pounding bass that poured out the open doors of double-parked Cadillacs. A piece of those Friday night rituals lived throughout the week, following us back to our homes and schools. N**** was a forbidden claiming of space and each other. It was familial and community. Parents would add “Lil” to the front of it when they were disciplining their children. As adolescents, we did what children do … turned it into a rhyme … “Honey Boom! Chedda Cheese … N**** Please!” But there was also a heaviness to it. My mom never used the word, and somehow I knew I was never to use it in front of her.

By the time I was in ninth grade the world changed for me. East Oakland was under siege. The crack cocaine that flooded our communities turned our schools into battlefields. My mother made the decision to use her godmother’s sister, Granddear’s, address to get me into Berkeley High School. Each morning, I would wake up at 5 a.m and take the public bus more than an hour to hippie-town, where I met Mr. Richard Navies—a man to whom I owe my life. Berkeley High was the only public school in the nation with a Black Studies Department and Mr. Navies was the larger-than-life figure who served as its chair. Ninth graders were immediately reprogrammed to love who we were as Black people, to understand Black culture and history as something worthy of study, and to replace the “n-word” with “Brother” and “Sister.” You see, the “n-word” was not some reclamation of Black community; it was part of a process of dehumanization required by chattel slavery. We weren’t human beings; we were n*****. I have not used the word since walking into Mr. Navies’ class. I was 13 years old.

Jody Armour has been a good friend, a colleague, and a comrade for almost 20 years. Still, it has been challenging for me to even follow his Twitter handle, which bears the name of this book @N****Theory. When he invited me to write the foreword, his brilliance, commitment, and deep love for our people took precedent over my own discomfort with the word. His work has challenged me to be deeply introspective, to grapple with my identity, my beliefs, and my outward praxis. It has forced me to question and to grow.

This volume is not about the word, but about the imposed dichotomy between “Black people” and “n*****s.” It is about the strategic and ethical decision to align with n****s, especially when we have the option to be seen as “good Negroes.”

On February 26, 2012, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was murdered by aspiring white supremacist George Zimmerman. Zimmerman was arrested only after a massive public outcry and deep community organizing among Black Floridians and across the nation. Trayvon was not the first Black boy to be murdered by a vigilante who was protected by the state. In the years leading up, social media and video recordings had raised awareness and sparked outrage in Black communities. In writing about Oscar Grant, journalist Thandisizwe Chimurenga called these state-sanctioned killings “double murders”: the theft of the body and the assassination of the character. I would actually make it a “triple murder,” adding the killing of the entire community’s standing. As media elicited sympathy for George Zimmerman, the white-passing child killer, Trayvon was somehow transformed from a fun-loving high-schooler into a vicious-truant-gold-tooth-wearing-weed-smoking thug. Trayvon was cast as a n****, sub-human, property. As Trayvon’s parents and community were fighting to bring some semblance of justice in the actual killing of Trayvon’s body, they simultaneously had to defend his character. Online campaigns of celebrities wearing hoodies and people with Trayvon’s favorite snacks—Skittles and Arizona Iced Tea—were meant to reclaim Trayvon’s innocence. As it became apparent that the “justice” system had no intention of providing justice for Trayvon, the reclamation of his character became paramount. There was a community struggle for Trayvon to be seen as a child, a good person, not a n**** … and for the Black community at large to also be seen through a humanizing lens. This struggle for the humanity of our children following the theft of their bodies by police and white supremacists repeated itself with each state-sanctioned murder. Each was heartbreaking.

At the two-year memorial for #AndrewJosephIII in Tampa in 2016, Deanna Hardy-Joseph, the 14-year-old’s mother (who is also my cousin), recounted how Andrew was perfectly-mannered, a scholar-athlete, never in trouble, a joy. The Josephs were Huxtable-level perfect; the parents, Andrew (the elder) and Deanna, had been high school sweethearts, were college-educated, professionals, lived in a gated community, invested in charity work, and had two smart, charismatic, beautiful children—Andrew and Deja. They survived intact despite being ravaged by Hurricane Katrina and having to resettle from New Orleans to Tampa. It was outrageous that 14-year-old Andrew—a kind boy, who was simply trying to help his friend who was being harassed by police at “Student Day” at the County Fair—would be targeted, detained, strip-searched, labeled a gangster, removed from the fair, dumped on the side of the freeway (along with five others … of 99 total “ejected” that night … all of them Black boys), and marked for death by police. As Deanna’s shiny round face, perfectly-shaped mouth, motherly softness, with hauntingly sad eyes, tells the story to the crowd circled-up outside the fairgrounds, we are all outraged that they could treat her son like less than a dog. Our chests fill with rage and pain. There is stillness in the circle. Then #CaryBall’s mother steps forward. She had come to support Deanna from St. Louis, where Cary had been an honor roll student, with a 3.86 GPA, high ambitions, promise … .stolen by the gun of a police officer who didn’t see who he was; they saw him as a thug, a n*****. Mike Brown, Sr. then moves in. He spoke of how his son #MikeBrown planned to become an aircraft mechanic, of how he loved his grandmother, of his warmth, of who he was as an 18-year-old young man and how Ferguson police portrayed him as an animal, a brute.

As we stood in that circle, the warmth of the Florida sun baking in the tears that flowed freely, I thought about my own three children. None of them had a 3.86 GPA. My middle daughter was a “free spirit” who could often be found under her desk at school, carried slime in her pocket, spoke out of turn in class, found humor in everything, and laughed loudly, defiantly, in a manner that filled entire campuses, and frustrated teachers, administrators, school police…and her mother to no end. My oldest is a born revolutionary, who regularly challenged authority, and organized others to do the same, especially in the face of white power-holders and “good Negroes” who propped up racist institutions. I couldn’t say of them what these parents were saying of Andrew, Cary, and Mike, but weren’t they worth their lives, too?

Why must our children be perfect to live? Why do they have to pull up their pants, or get good grades, or be respectful, and have ambitions, to live? Why can’t they be children who hop fences, cuss when they’re out of their parents’ earshot, smoke a little weed, hate math, have dangerous-joyful lives, make mistakes, and recover from them? What if Yuvette shoplifted at Home Depot? What if Ezell jaywalked? What if Mike stole cigars? What if Redel robbed the pharmacy? Or if Devin went for a joyride in his dad’s girlfriend’s car? What if Jesse were tagging? What if Wakiesha cussed out the prison guard? What if Kisha and Marquintan were high in the car? What if Richard spent his childhood in Youth Authority? Or if Carnell had a gun in his waistband? What if AJ were in a gang? I’m not saying that any of these things are true, but what if? If the folks on whose behalf we struggle weren’t perfect, if they were n*****, are they not worth their lives?

White-supremacist-patriarchal-heteronormative-capitalism socializes us to aspire to “good Negro” status. It convinces little Black girls from East Oakland to graduate from Howard—summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa, to pledge the oldest Black sorority, to earn PhDs, to be in the “right” rooms … with other “good Negroes,” to learn to taste wine, to only laugh intentionally, to favor jazz over hip-hop, to submit to a political and social grooming process that sets us up for “firsts,” titles, and the illusion of power. It convinces us to revel in exceptionalism, that there is a such thing as individual advancement, and that those who are denied pats on the head by benevolent elites are somehow inferior. We are told that to buy in is not the same as selling out, that we can be a “credit to our race” without being of the people. “Good Negroes” are not n****s. We are trained to have disdain for them, to despise them, to deny the n**** within our own selves, to redeem ourselves from it, to kill it. But our position as “good Negroes” is tenuous. It’s bestowed by a power structure that preys upon us, but requires us few to veil its existence.

—

Killed just two days after #MikeBrown in Ferguson, #EzellFord became the touchpoint for Black Lives Matter organizing in Los Angeles. The 25-year-old, intellectually-disabled Ezell was well-known and beloved in his neighborhood, 65th and Broadway, a space where young Black men were especially targeted by police. LAPD officers Antonio Villegas and Sharlton Wampler were harassing Ezell on August 11, 2014. They escalated, got him face down in the street, and shot him point-blank in the back. The official autopsy showed a muzzle imprint burned into Ezell’s skin, likely the fatal shot. The neighborhood and Ezell’s family were retaliated against for speaking out; police berated his family, ran up in their house, and arrested one of Ezell’s most outspoken cousins on an “unrelated” charge. Community outrage sparked Occupy LAPD, an 18-day, 24-hour encampment in front of LAPD headquarters that ran from December 2014 to January 2015. LAPD Chief Charlie Beck justified police actions. As the Civilian Police Commission prepared to rule on whether or not Ezell’s murder was in-policy, we knew it was important to pressure the mayor, who appointed the commissioners.

On Sunday, June 7, 2015, two days before the scheduled ruling, about a dozen of us, dressed in white, prayed together and sang spirituals as we filed down Irving Ave., gathering in front of the wrought iron and brick fencing that encircled the mayor’s mansion. I had been to the mansion before, gathered in its lush gardens, eating decadent hors d’oeuvres, blending in with women of means decked out in flowery dresses and floppy hats. I knew Eric Garcetti. We shared mutual friends. He’d given me his personal phone number just months before. I was being considered for commission appointments and had been contracted by the city as a researcher. I was on most “good Negro” lists, and the Black elite often saw me as next up in the line of Black political succession.

It was still dawn when we knelt at the front gate and poured libation in Ezell’s name. As the sun rose higher in the sky, we took to social media, pledging to occupy, challenging the mayor to come out, and finally catching him trying to leave out the back door the next morning. We blocked his blacked-out SUV with our bodies. As I approached his open window, I could feel my fledgling good-Negro status slip away.

I’ve been arrested six times as a part of movement work (after a few times as a juvenile … for less noble reasons). I have been threatened with trumped-up charges that could have gotten me some serious time. I’ve been threatened, surveilled, intimidated, and physically roughed-up by police. I’ve been doxed by white supremacists. My children have been targeted and placed on lists. My name no longer appears on lists for official gatherings. I’m no longer the “good Negro” at the dinner table. The husband of a public official pointed a loaded .45 at my chest and said, “I will shoot you.” I have plummeted from the “good Negro” pedestal upon which I was once positioned.

The truth is, such status is always illusory. It is never assured. The pedestal is always wobbly. The truth is, we are all n****s … even when we pretend to be “good Negroes.” We must not reach for a status that is only bestowed by a white supremacist system that really despises us. We must resist. To claim not only our alignment with n****s, but our identity as N****s ourselves is the greatest act of defiance; it is our sacred duty as descendants of enslaved people, freedom fighters, street corner hustlers, and our own grandparents. Ultimately N**** theory—and praxis—is what will get us free.