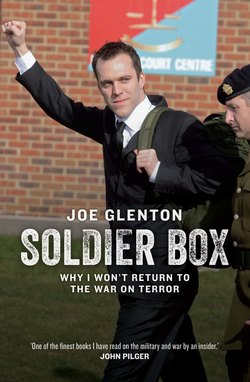

Читать книгу Soldier Box - Joe Glenton - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction: Remand, 2009

It’s December. I’ve been put in prison for opposing the war in Afghanistan. Lots of other people disagree with it, lots of people think it is variously a stupid or illegal or unjustified or doomed war. The problem is that I am not supposed to say these things because I am a soldier; and yet I keep saying them.

Remand is when you are held in prison awaiting trial. Sometimes it is for those considered a flight risk and at other times it is for those not yet tried and convicted but considered too dangerous to be out in the world – I belong to the latter category. What I have said damages the ‘war effort’ and I have said it with that intention. Remand is purgatory.

They tell us it’s not a prison, but we can’t go out. We’re held in a centre for corrections. I find irony in that idea and in the idea that the individuals who’ve sent me here actually believe it is me who needs adjustment. The Military Correctional Training Centre (MCTC) claims to improve soldiers or discharge them as good citizens. To me it’s a funny idea – funny ha-ha, and funny strange.

I share my room in the remand wing with three others. It is here that we play cards at a table in the centre of the room. The others are regularly distracted by reality television, which they love and I hate equally. Summers comes from a Scottish regiment. I knew him briefly at the Defence School of Transport when he had been a trainee vehicle mechanic. He later switched trades to the infantry and now he has an Afghan medal, three counts of AWOL (five, eight and 133 days) and post-traumatic stress disorder. In line with unofficial tri-service policy, it would not be diagnosed, treated or taken into account for his court martial, despite his history and symptoms. After returning from a harrowing six months in Helmand he drowned himself in drink and drugs. His teenage girlfriend and his parents had posted him as a missing person when he disappeared for several days, sleeping off some chemical stupor. His unit posted him AWOL. Returning to duty, he claims, his sergeant major told him not to go sick with his condition because mental illness ruins careers.

Tommy is an Ulsterman. He has an English father and an Ulster-born mother and claims he is a militant. He talks passionately about flute bands – which he pronounces flute ‘bohnds’ – and paramilitaries like Johnny Adair and ‘Top Gun’ McKeag. He is heavily tattooed and has a star inked underneath one eye that signifies an illicit deed carried out for the paramilitaries. He is in the logistics corps, like me. Tommy has attracted charges for ABH, AWOL, Drunkenness and Stealing a German Army General’s Bicycle While Drunk. In between playing hands of Shithead, Tommy draws vibrant loyalist images on the back of a notepad: A5 sectarian murals, like the sides of tiny Irish houses. He flips it over occasionally to tally scores.

Trevor is the final player. He is small, muscular and loud. He argues with the screws at every opportunity and is the serial door-kicker during lockdown. He is a Kingsman (a private in the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment), and is in for AWOL and GBH, which he hopes will be dropped to Affray. He and Summers have shaved their heads completely, and for this crime they have been given extra duties, mopping and buffering the floors with an ancient, unwieldy buffing machine. Regulations say that a grade 2 is the shortest cut allowed without a medical chit.

Summers was a veteran of Afghanistan, Tommy has been there twice and Trevor has done Iraq. Two of them have young children, but these men drift from mature and robust to infantile and mischievous, always irreverent. They talk about shots fired in anger, IEDs, RPGs, ambushes, natives and mortars that missed them and sometimes hit someone else. Near misses and drunken brawling are favourite topics. They laugh often.

They are veterans, sons, parents and thugs. They represent the collected scum of three British nations and their average age is twenty-one. Now they are prisoners on remand. Waiting to be forgiven or reconditioned with or without discharge at the end of it. They are problems to be solved. Men reduced to Ministry of Defence forms.

Life in the military is transient. I will meet Summers briefly again after I am sentenced and sent back here to the prison as a DUS – a detainee under sentence – a convict. The others have become just names and fragmented memories to me. But here for a short time we are still soldiers and so we treat each other in a soldierly fashion. We share tobacco, play cards, nominate people to get the brews and abuse each other verbally. Abuse between soldiers is most often an expression of solidarity; in fact, it’s the main expression of solidarity. Soldiers cannot always guarantee an opportunity to die for each other, but they can always rip into each other and this process reinforces the bonds that the army wants to see: men who can say anything to each other and still coexist. The trick is to never bite at someone’s abuse, just have a go back or shrug it off. Any other response is weakness and will be rounded upon and must be rounded upon and should be. Never, ever bite when you are baited. This is our culture; the only stable thing in our unsettled lives is that ours is an abusive, masculine and transient world.

I was sent here to be silenced, having performed my own small acts of dissent. My incarceration was malicious revenge from my bumbling superiors for having dragged them through the mud. I have outed them in public, a taboo that breaks all the rules. I have questioned what is going on in Afghanistan and this is my punishment. The military is meant to be a silent leviathan but they have bitten. The ripples my actions have caused ruin the illusion of efficiency, strength and accountability, and of grim-faced adherence to duty at any cost.

The problem is that as much as they would like to think it, I don’t work for them anymore. Nevertheless, I am afraid, as they want to send me down for years – my own officers have assured me of this with confidence. I have a life and I want to get it back. This time on remand will come off any later sentence. But what, I ask myself, if it is years? The charges against me indicate a punishment, which may stretch for tens of years, if they have the balls. The only thing that keeps me playing cards, and not giving in, is my view that I am right to defy them. I am right, they are wrong – fuck them, fuck the toffs and the politicians and the army.

When my fellow prisoners ask me what I’m here for I tell them. Brows furrow. ‘Talking to the media? Can you get done for that? That’s bullshit, mate, you’ve been stitched up!’ And it’s true, this has never happened with regards to Afghanistan: my protest was public and my detention rests within a legal grey area. I argue it is unlawful. But the law here is solely interpreted by my captors to suit their immediate needs. There were once two charges for disobeying orders but these were dropped weeks ago, a judge confirming they were removed in a hearing. There are five more charges being considered. These charges are either dead or not yet born. They don’t know what to do with me, because I am attacking them with all the bloody-mindedness they instilled in me and I am doing it well. ‘They don’t like the sunlight,’ my legal man said of the coverage. ‘It makes their slime dry up.’