Читать книгу Soldier Box - Joe Glenton - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

I reached the small Surrey train station in the sunshine to find a horde of other recruits. You can spot them easily, even when you are one of them: we were all jittery, with cropped hair, and trying to butch up. We were led onto a bus and delivered through the gates of Army Training Regiment Pirbright to begin the Common Military Syllabus (Recruits). Rallied by an ancient, shouting corporal, we were marched through the camp to our accommodation. We were out of step and looked ridiculous; we knew nothing about anything here. Then we were fed and issued with a whole number of green and camouflaged items, many of which we never learnt the use for: a confusing mass of camouflage clothing, webbing, pouches, aide-mémoires, straps, respirators (gas masks), chemical warfare suits.

The base itself was spartan, industrial-smelling and every building and fixture seemed worn by either a lack of care or perhaps too much scrubbing, polishing and sweeping – it was hard to tell. Everything was ‘bullshit’ according to the other recruits, or at least the ones who spoke to us, because there was a hierarchy based on time spent here. The recruits who had been here the longest looked at us with scorn and mocked us. Even to the other recruits we were fresh, and to the instructors we were even lower than that. This camp turned normal people into soldiers bound for different parts of the army: privates for the logistics corps, troopers for Household Cavalry and gunners for the Royal Artillery. But at this stage we were all just called Recruit.

On our first night we were called to the central room of our block for the corporal’s amusement. We sat on the floor wide-eyed and nervous – forty new bonehead haircuts and standard issue tracksuits. ‘Okay, lads,’ the squat corporal told his captives, ‘if at any time while you’re here anybody tries to bum you, you should take one for the team!’ We laughed the laughter of sycophants. ‘And remember,’ he waggled a finger, ‘you’re only gay if you push back.’

From then on you had to march everywhere and call people by their ranks – even privates. This reminded us that we were only recruits. I only failed to do this once when I was peering through a window at a squad of recruits marching past the scoff-house (mess hall). Their tiny Scots corporal saw me, halted them perfectly and then ran to confront me. Staring up at me, he raised himself on tiptoes. ‘You eyeballin’ me, wee man?’ he slurred in his near-impenetrable Glaswegian. He was slight, wiry, and glowed alcoholically. ‘No, mate,’ I assured him, unsure of the penalty for having eyes. His face reddened. ‘Mate,’ he rasped. When I explained I was in Week One he let it go, satisfied he had beefed himself up to those present. He scuttled off and switched his abuse back to his own charges.

For the first few days the corporals were limited to shouting at us. The regulations said they couldn’t damage us until we had passed a medical. Once the medics had checked us over we were fucked about at all times as we stumbled through the fundamentals: boot polishing, uniform ironing and foot drill. Within days we started to bond by ransacking each others’ rooms dressed in gas masks, boots and full green, military long johns in the dark hours. We adopted soldierly habits, swearing, fighting and piss-taking, and the weakest were routinely turned upon.

The transformation had begun. But we were still only panicky recruits, our first names trimmed and replaced with numbers. I was now 25193317, Recruit Glenton. We were always alert to the shouts around us and always relieved when it was someone else being ripped into. Our lives and value were measured in weeks served. People would ask each other what week they were in, and this provided a hierarchy. The first serious test was to carry out a set of drill movements as a squad on the parade square. After this you could march yourself to eat bad food, rather the being marched by the corporals. This seemed like a privilege to us.

I was starting to love it, the marching and the shouting and the joking and the new friends. Even the language started to seep into us: fuck this, cunt that, and wanker everything and scrote-bag every fucker. On weekend leave I found this language jarred with the real world. Fuck it, I thought. Who needed the real world? I was going to be a soldier forever. I went back to training eager and feeling like I should have joined earlier and not wasted years in dead-end jobs in kitchens and factories. I was good at this stuff and it was little strain. Just turn up on time, pay the compliments, salute the posh blokes, call the corporals corporal and the sergeants sergeant, charge around the woods, iron your kit, get paid – easy life.

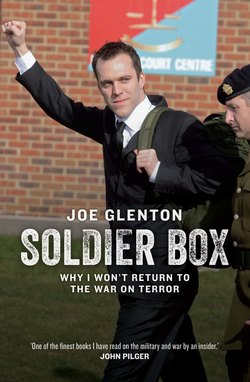

We had been taught to strip our rifles down for cleaning, except sights and a few other parts which were reserved for armourers. This would have been ‘illegal stripping’. On the ranges during our shooting test my rear sight had come loose and, as it slid free, I got increasingly inaccurate. We were not allowed to adjust them. I told our sergeant this and he told me I should have adjusted it. In the army, this kind of thing is called ‘being seen off’. This means being stitched up and is what happens in the Soldier Box, away from civilian eyes and universal sense. I failed the test, was sent back – ‘back-trooped’ – by a week to retake the test, and re-assigned to another troop that was a week behind us.

In this new group – Peninsular Troop – we were taught by infantrymen from the Guards and the Green Howards. The guardsmen were cracked: they told us that in the Household Division the word ‘yes’ did not exist. Instead, they just said ‘sarnt’ (meaning sergeant) as a matter of etiquette. It is the only approved affirmative in the Guards, they said. In addition, when they entered and left the parade square for drill practice they halted and saluted the concrete expanse; drill was religion to them. One of them told us that when we had our final passing out parade we should aim to be so crisp, so smart and so superb that our very posture and bearing seemed to bellow to the onlookers: ‘Look at me. I am chocolate. LICK ME.’

The Green Howard was from the north of England and hated southerners. He would single out a particularly southern-sounding soldier and repeatedly scream ‘Dawkins, you are a cunt’, into his face in his best cockney accent. He was bitter about having got all the way through SAS selection only to be rejected. His personality hadn’t squared with the Special Forces. We felt this was understandable. I later heard he was kicked out of the army, something about punching recruits.

At times we would hear our names bellowed as the NCOs summoned us for a round of abuse. We’d stop what we were doing and scuttle out of our rooms, snap to attention at the door of the central room, and rattle off our names and numbers. ‘Ah, recruit so-and-so!’ one of them would cackle, ‘come in.’ They would lounge around the edge of the room as we were interrogated about nothing in particular. ‘So, recruit so-and-so,’ one corporal would ask as others looked on, ‘tell me, have you ever tasted your own semen?’ Any laughter from the subject would be met with a demand to know what ‘the fuck’ was funny. Do you think you’re hard? Or funny? Are you a fucking joker? Are you a clown of some kind? ‘No corporal’ would be the only acceptable reply.

‘So Glenton,’ I was asked once, ‘what is THAT?’

‘Corporal?’ I asked.

An accusing finger shot up to point at a mole under my eye. ‘THAT. Is it a fucking Coco Pop?’

This was accompanied by a new round of chortles.

‘Yes, corporal, it’s a Coco Pop,’ I confirmed.

‘Well be more fucking careful at breakfast then, Recruit Glenton.’

We soon moved on to weapons training, field craft, more drill, tabbing (marching or running with a backpack) and lots of time in the gym wearing ridiculous blue short-shorts. As some kind of encouragement our corporals would egg us on: ‘You’ll fucking run when you’ve got twenty hairy-arsed Iraqis chasing you.’

The corporals were often angry – our stupidity was painful to them. One day on the firing ranges, as we lay with our elbows crunching in the damp gravel, firing rounds at the targets, one of our number managed to upset an instructor, a mouthy southern corporal. We all froze as he rounded on the recruit, who had shot an angry look at an NCO. ‘If you ever fucking look at him like that again, chicken lips, I’ll fucking shoot you myself!’ He checked himself as we all looked on. ‘Don’t tell anyone I said that,’ he added. We all shifted our gaze, straight down the range for the rest of the day. Staring down the lengths of our rifles we revised in our minds whether chickens had lips.

We were up early and late to bed. I found the fatigue manageable after the initial shock and was determined to pass through with minimal fuss. Some people left after a few weeks, citing a change of heart and I thought them foolish. I reasoned that this period did not represent the army per se; it was a rushed, half-cocked introduction. I kept my head down, blending in as much as I could; the last thing I wanted was notoriety. I was once even pulled up for my obscurity in a report. A Scots corporal – one known to lift his kilt during drill practice to expose what he termed the tartan torpedo – told me I needed to look like I was struggling more, otherwise I wasn’t trying. I told him I would struggle as much as I could. I felt at all times like a fellow traveller – other people moaned and griped and I pushed on. There was no way that this would beat me, it wasn’t even the proper army yet.

We were taken on a battlefield tour of Belgium and France. We saw graveyards of grim, dark stones for the Germans and white crosses for our lot. Here and there we stopped and looked at surviving fortifications that seemed to spring weirdly out of rolling green farmland. We visited the Menin Gate – a monolithic war memorial – where a select few were allowed to lay a wreath at the service while the rest of us looked on and tried to feel morbid. The occasion was treated very seriously and seemed to demand seriousness. Our instructors told us we should think deeply about this because some of us would die soon in the wars. I thought deeply about this and quietly dismissed the idea that it would be any of us getting killed. I do not know if any of my friends from training died, except one of our sergeants who was okay to us and stole our fags a lot. ‘If you’re smoking,’ he would say in his Sunderland accent, ‘then sergeant is smoking.’ An IED killed him in Afghanistan. He was a guardsman and only thirty years old.

After the first weeks of training and the battlefield tour we began to spend more and more time out in the training area, learning to survive the cold and lack of sleep, and doing what one of our instructors termed ‘aggressive camping’. I liked being there, even though it was uncomfortable and the exercises were very basic. It felt good. To start with we would tab out and then form a ‘harbour’ area, a circle of outwards facing pits in which we lived and pretended to die when attacked. We would then do patrols and reconnaissance, and at night we would get attacked. If we lived we would bug out (retreat) in the dark.

Our troop commander, a lieutenant from the Grenadier Guards, schooled us in what to do when attacked. He carried himself like a man whose ancestors had commanded common scum like us at Waterloo. ‘When one is ambushed in the harbour area,’ he told us, ‘one must get out of one’s scratcher (sleeping bag) and pack one’s bergen (backpack) aggressively.’ When attacked we packed our bags violently and mock-fought our way out, running into trees and each other. Afterwards the instructors would bring us back and we would look for all the things we’d left behind: sleeping bags, mess-tins, rifles, boots, other recruits and packets of sweets. A ‘beasting’ (hard exercise) followed and Willy the Whistle became our master. We’d have to crawl a muddy circuit on our bellies on one blast, run on two blasts and do press-ups in the mud on three – all with the stated aim of making our eyes bleed.

The officer took us out to learn how to do a reconnaissance patrol, a particular type of manoeuvre which we were told involved the maximum of stealth and field craft. ‘So are we going to sneak around, sir?’ I asked him. He scoffed disparagingly, ‘The British Army does not simply… sneak around.’

None of this felt particularly real. In fact it felt like we were doing most of our exercises on a rubbish tip. The landscape was strewn with empty ration packs which soldiers were meant to bury after use. Animals dug these up so all our training areas were covered in plastic and the debris of pretend warfare. Another hazard was left over from years of shovel reconnaissance, where a man, his rifle and a shovel travel out into the bushes to shit. Her Majesty’s restricted woodlands of Britain are mined with shit and plastic. This tactical activity – once known as ‘Squat, Squeeze and Cover’ – was now frowned upon and Portaloos had been scattered around the woods where soldiers would go for their tactical field shits. We were told to patrol in groups, or at least pairs, to these brightly coloured shrines in a proper soldierly fashion.

Once in situ, you peer into the woods over the sights of your weapon to protect your comrade while he squeezes inside the toilet with his webbing, rifle and helmet. You then switch. This is preparation for the war. We were told they have portable shitters in Iraq and Afghanistan as well. Portaloos, I figured, are omens of freedom and democracy in the sand and are rated among our greatest weapons in the War on Terror.

Training continued to be good fun. We were forming bonds with each other, except for a few ‘gobshites’ and ‘jack’(selfish) bastards. When our fights broke out the instructors would stop them but they were not overly concerned. After all, we were learning how to survive, fight and kill – albeit in a rudimentary way. We were only destined for the corps, not the infantry. They’re the ones who do the real killing. Rudimentary killing was our game. We would not be considered fully trained until we had been at our units for six months. But, as the instructors told us, if you kept your mouth shut, turned up on time and looked like you were struggling you would get through it.

Our lives were punctuated with ‘show parades’, a punishment for such sins as inadequate ironing. You had to give a bold, clear announcement for the inspecting officer: ‘Sir, 25193317 Recruit Glenton, Peninsular Troop, 105 Squadron RLC, week eight showing combat trousers properly ironed, sir.’ During one of these punishments the scruffiest officer I had ever seen emerged from the guardroom. He was an outrageous toff with hair down his back and a stupid accent down pat. His uniform was in what we called shit-state and a swollen black Lab wheezed at his feet. All he needed was a Barbour jacket and a shotgun. He looked us up and down paying no attention, and then orated, ‘Clearly, it’s imperative on operations around the world, in places like Irarrrk, B’zzniaar and Arfgarnistaarrn, that we need smart, well-turned out soldiers. I do not wish to see you here again.’ He swaggered off and left us wondering where we’d plug in the iron in the desert. The duty sergeant met our gazes, and shrugged. ‘What a cock,’ the sergeant said. Senior NCOs alone do not fear officers, unless they have maps in their hands and want to navigate.

Every soldier in every army has stories from training, all rooted in the same themes – screaming corporals, early mornings, and inspections with unattainable standards, bullshit and violence. It was here we were lectured in the ‘Values of the Army’ by the padre: Courage, Discipline and Respect for Others, Integrity, Loyalty and Selfless Commitment. It is strange now to have learned about ethics in the army and from a priest of all people. Apparently, this is what priests are meant to do. Having been raised beyond God’s earshot, I had no idea they were other than decorative. Iraq and Afghanistan, I would find, were conflicts that required moral vaccination.

There were also informal lessons on what we were being trained for. We endured nuclear-biological-chemical warfare lessons – during which we were CS-gassed while the instructors filmed our trailing, gas-induced snot and misery. We were also taught that when a nuclear blast wave comes it is called a positive wave. This name is deceptive – it does not mean the wave is essentially good. Because of this essential un-goodness we are to lie down. When it returns we should still be prone – this wave is called the negative wave. We lie down so that we may continue to fight after the nuclear detonation. Presumably, our fight would be with whoever else had known to lie down and over whatever is left to fight for after a nuclear blast. After this lesson we were assembled and told by an instructor that whatever our job, our goal was to ‘kill cunts’, or to get others into a position where they could ‘kill cunts’. We were all about cunt-killing.

This disparity between the padre’s line and the one we were to apply was clear. After our Values and Standards lessons, once we were marched out of the padre’s proximity, we would be told, ‘Don’t listen to that soppy old fucker. Just do what you are told, that’s all you worry about. Thinking is out of your pay scale.’ Soldiers do not work with the padre. He is normally trying to get people to talk to him and stop hiding when they see him coming. Soldiers, however, are rarely out of sight of NCOs. We took our cues on ethics from the NCOs, who would beast us and occasionally threaten to shoot us, not the priests.

At the end of our training, when we had passed all of our basic tests in shooting, marching, obeying and being abused, we had a passing out parade – a ceremony where we marched around the parade square in front of our families before being inspected by a senior officer. We carried out some overly elaborate drill moves as a full troop of thirty or so soldiers. We managed to fluff most of it and after we’d finished a visiting colonel strutted our three ranks inspecting, fawning and talking rubbish to us. I was unmoved. I had no family there to see my shiny toecaps and no. 2 dress (formal dress). It was my own day. I was going to be a soldier now and felt like I was part of something good and wholesome.

The logistics soldiers were sent down the road from Pirbright to Deepcut in order to learn to steer ourselves and others towards or away from violence, depending on the situation we would be facing. We were still treated like children, but called private instead of recruit. Many of our families were more concerned about a son posted here than to Iraq. Deepcut was a grim old training camp – home of the School of Logistics – and had a sinister reputation. By this time pickaxe handles had been swapped back to rifles for the guard shift, as a number of recruits had managed to shoot themselves in the head multiple times. A huge legal battle had ensued with much squirming from the Ministry of Defence and Army. We never pressed the topic.

At Deepcut you stayed quiet and tried to get through your course as quickly as possible. After my trade training I was put into a driving course. This consisted of a week or so of intensive lessons and then test after test until we either passed or were made to be chefs – chefs did not need to have a vehicle licence. We were constantly threatened with being forced to become an army chef – no one there wanted to be an egg-flipper or a cabbage technician. I did six driving tests and barely managed to escape.

I was despatched with three other soldiers on an otherwise empty coach to the military driving school to do our truck licence. We sat in the hangars of the old airbase for days at a time waiting for someone to pass their test so we could take their position. When this was finally done I returned to Deepcut and did two weeks of guard, standing on the gate in all weathers as people came and went. We stopped and searched random cars to punctuate the boredom. I had asked to be posted to Colchester, which was approved. I was despatched for some pre-posting leave with papers telling me not to be late to my unit.