Читать книгу When the Music Stops… - Joe Heap - Страница 7

1. The Child

ОглавлениеTHE STORM WAKES ME. It must have been going for a while. The boat is rocking like a rollercoaster and the sea is loud. I squint at my clock. The red numbers say it’s half two in the morning, but this clock hasn’t been set since we left … where was it we left? Somewhere else. Somewhere not home. I can’t guess the time these days. Now that I’m an ancient ruin. I’m not sure how long I slept. I stare at the flashing dots on the clock: : : : : : :

Someone is banging at the door.

‘Mum? Are you awake?’

‘Abigail?’

The door opens. ‘Yes Mum, it’s me. Do you mind if I put the light on?’

‘Mind? Why?’

The light clicks on and there is Abigail. She looks flustered, and she’s hanging onto the doorframe. The bedroom tips to one side.

‘Are you okay?’ Abigail staggers over and sits on the side of my bed like a nurse. She was a nurse, before this. Her auburn hair is unbrushed and I want to get a comb.

‘I just wanted to check you’re okay.’

‘Why?’

‘Because of the storm.’

‘Oh … Bad?’

Abigail sighs. ‘Yes, Mum, it’s pretty bad.’

‘Don’t need helping.’ I look up into my daughter’s face. She has freckles but no wrinkles. She’s still so young.

‘I know you don’t need helping, you stubborn old goat.’

I make horns with fingers at the sides of my head and bleat. Abigail laughs and kisses my forehead. ‘I just need to help David secure the boat, and I don’t want you to worry if you can’t find me.’

I take a deep breath. ‘Don’t worry. Go. Take care.’

The older I get, the less I talk. The words are still there in my head, I just can’t get them out. Or if I do, they’re wrong. I say ‘knife’ when I mean ‘fork’ and ‘hello’ when I mean ‘goodbye’. I used to be a musician, and I preferred playing music to talking. Maybe this is nature’s punishment – use it or lose it. Meanwhile, the trapped words boil away in my head like the contents of a pressure cooker. Long, rolling sentences bubble up. Presumably in this metaphor my brain is the old piece of meat, liquefying in its juices. I don’t like it but there’s nothing to be done. I sling one arm around Abigail’s neck and half-hug her.

‘See you soon, Mum. Sleep tight.’

Abigail clicks the light off and closes the door. I settle back into bed. The storm seems worse, in the dark. I feel it throwing our boat up and down. Out of habit, I count the things I remember.

1) My name is Ella Campbell.

2) I’m on a boat.

3) I’m on the boat because I’m on holiday.

4) I’m on holiday with Abigail, the baby and … and … him. Abigail just said his name, but it never seems to stick in my head.

5) The boat belongs to ‘him’.

I wish I could remember his name. The man who brought us on holiday. He wears a lot of aftershave and thinks that because I am from Glasgow I must be mad for porridge and bagpipes. The only places he’s visited in Scotland are golf courses. He bought this boat and he’s sailing it back to England. He’s a roaster, but I don’t tell this to Abigail.

Another wave breaks over us. The boat shudders and I feel sick. Perhaps if it weren’t so dark, I’d feel better. At home (The Home), I have a light that comes on when I clap. I try this, but it doesn’t work. Perhaps the light can’t hear me over the storm.

‘Abigail?’

There’s no reply. Abigail will come to check on me, of course. Over my bunk, on the right-hand side, is a window. Push yourself up with both hands. Careful, you old codger, feel for the porthole. I touch my nose to the cold glass. On other nights there has been a moon or stars. One night, the ocean looked like silver velvet being shaken over a stage. I remember the Palladium … or was it the Lyceum? I don’t remember the show. There’s no light now.

I’m about to get back under the covers when the boat lifts

up,

up,

up …

It’s like a hand is scooping us out of a bathtub. I feel weightless.

Now the boat drops again, smacking the waves. I’m knocked backwards, out of bed and onto the cabin floor. For a moment I forget to breathe. The pain follows. I can hardly hear my own cry. There’s not much space between the bed and the door, and I’ve hit my head on something. It’s still dark except for the glow of the clock. This is awful. When I next see Abigail and him, I’m asking to go home. I don’t want ‘one more adventure’, as he calls it. He doesn’t know the meaning of the word.

I’m near the door, so if I reach up, somewhere above me … my fingers brush a pom-pom, dancing at the end of a string. I grab hold and pull. The light comes on. My legs are tangled in white sheet. Get up, don’t lie on the floor, get yourself sitting. I could try to stand, but the boat is still bucking and I don’t want to be thrown again.

I crawl to bed and settle down to sleep. But I can hear something. Very faint. I’m not hearing it through the air but through my pillow. It’s coming through the floor, through the walls. High and thin, almost drowned out by the storm.

A baby crying.

My mouth curls up in a smile. My grandson. He is four months old. Or is it five? Too young to be dragged out on this boat, just like I’m too old. Thunder rattles my chest as I think about the baby. If the memory is hazy, that’s just what babies are like. Blurry, not-quite-developed. One day he might be a judge or a poet or a landscape gardener. But we can’t see that yet; he’s keeping it to himself. I hope he’s not too miserable. The sea has been making him sick. How long have we been on this boat?

I open my eyes and stare at the light. Abigail could be with the baby. Sometimes he can’t be soothed, for all her trying. No wonder, in this storm. But the doubt is there in my mind, getting stronger. Abigail is good at soothing him. There’s something reassuring about her that she didn’t get from me. She must have been a good nurse, before he made her give it up. She says he didn’t make her, that she wanted to …

The baby is still crying.

The boat is rolling through hills and valleys. But what’s to lose, when you’re eighty-seven? I get to sitting, holding tight to the bed. The cabin light flickers and dies. I sit in darkness and say several words that an eighty-seven-year-old isn’t meant to know.

Deep breath.

I launch myself toward the door. The boat tips and I slam into solid wood. Out of the cabin, into the narrow corridor. That’s the one good thing about this cramped boat – never far to fall. In the dark, I feel the walls either side. There’s something else, an unfamiliar feeling. My feet are cold. There’s water in the corridor.

I edge along, legs threatening to mutiny. Opposite me are two doors, one Abigail’s room, the other a spare bedroom which has been the baby’s playroom. On my side is the door to the nursery.

‘Abigail?’

There’s no reply but the storm. I grab the handle to the nursery, but there’s more water in the hallway now, pressing against it. Are we sinking? One foot against the wall and both hands on the handle, I pull. The door opens onto the sound of wailing.

‘Abigail? Are you in there?’

No reply. My head swims with darkness. If there were light I would feel better. I can’t see the baby and there’s water in the nursery. That’s not right. I’m the one who opened the door, I’m the one who let the water in. Have I made a mistake? Too late to go back. I edge forward, guided by the crying. Inside there’s less to hold onto. Each cabin has a built-in bed, but the baby sleeps in a travel cot on the floor.

A cot which is level with the floor.

Hold onto the crying – he’s still there. The boat starts to race downhill like a bobsled. I grip the doorjamb just in time and for a moment all the water around my ankles is gone, washing to the far end of the room. The baby falls silent. Is he drowned? My fall is broken and I almost lose my grip. The baby coughs and screams.

This room is a mirror image of my own. Clothes have started to baffle me in the last year, the landscape of blouses and underwear leaves me frustrated. In the dark, this mirror-room is a cruel puzzle. There is a sudden flash of dazzling blue light. In that moment I can see the cot, can see the baby kicking his legs against the wet mattress. Then the light is gone, replaced by thunder. Before I can lose the image, I step forward.

The baby is frantic, his wails staccato, as though he can’t wait to draw breath before the next one. Not the cry of a baby who is tired, hungry or sick. A cry of terror. I feel over the mattress until my hands close around his warm, squirming body. Tiny hands grip the edges of my own as I lift him. He’s big for his age – I’ve never lifted him myself. I’m usually in a chair, propped with cushions. My vertebrae pop-pop-pop. His hot face screams into my ear.

‘Sssh, sssh, there now.’ He squirms in his soaked sleeping bag and batters me with tiny fists. ‘Come on lovey, I’m here now.’

My arms tremble with the strain. I just want to lie down and go to sleep. Maybe it’s safest if I stay here. Abigail must be busy, making the boat right. But then I remember the water – the water that I let in. We can’t stay here, it isn’t safe. How will I get him upstairs, in the dark? I remember his nightlight. It’s made of soft plastic, shaped like an egg. If you press on the pointy end, a light comes on.

I put him on the bed. I crouch down and feel in the cold water for the box of toys. My hands turn numb as I run them over rattles and teething rings, fabric books and soft animals. I throw the rejects into the water. Finally, I have it. The cabin is lit by blue light, shifting to green as I look to the baby on the bed, staring at me with his mouth an ‘O’. Regaining composure, he resumes his wailing.

‘Sssh, hush now, I’m coming.’

My head feels waterlogged. I get the baby as far as the hallway without much trouble. Then the boat tips back, like a rollercoaster climbing to the top of a big drop. I can see the stairs up to the saloon but can’t move toward them.

Wait. Wait for it …

The boat tilts a little, then we’re racing down, faster than before. I launch myself at the stairs like a nightie-clad Olympian. I catch the first stair with my foot, and the next. Though I’m climbing the stairs, it’s like running downhill.

We reach the top stair. We’re in the lounge, except now I can’t stop –I’ve too much speed and the tilt of the boat means that the wooden floor is a polished slide. My feet go out from under me and I land heavily. We slide across the length of the room and crash into the back wall.

I’m still holding the baby. There’s no way of telling whether I’ve broken any bones. Everything hurts. The deck here is wet, like downstairs, but there’s no water sloshing around. The baby squirms against my chest and the room is lit by changing colours. I look around and see the baby’s nightlight, rolling on the floor, turning red, then blue, then green. How did that get there? Abigail must have brought it to see by.

The door to the deck is flapping open, letting in rain. Papers skitter and Abigail’s novel flaps on the floor like a wounded bird. I shuffle to the door and shut it with one foot. The room is suddenly calm, though the storm still rattles the windows. In one corner of the cabin is the baby’s bouncy chair, with straps to stop him falling out. I shuffle over and put him down, then struggle for a minute to get him out of his wet sleeping bag.

I look around the cabin. On each side is a sofa. I can sleep on one of those. It will be comfortable. But the baby is still crying so hard. If I could feed him, he might be happier, but Abigail only gives him breastmilk. If I could just sing one nursery rhyme, maybe he would calm down. But with the sound of the storm and the baby crying, I can’t remember. What was that one – ‘Old Man Farmer’? ‘Clip Clop Horsey’? I try to hum, but the melodies have rusted away.

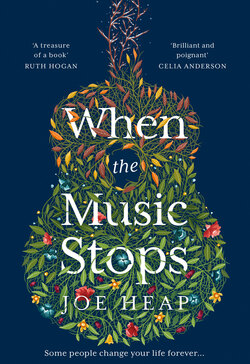

I look around the room, seeing by the ghostly nightlight. There’s a barometer set into a model ship’s wheel. There’s a picture of a Greek village, with white walls and blue domes and more sea in the background. There’s a guitar …

A guitar.

I fix on the guitar. It glows in the blue phase of the nightlight. I’ve seen it before. But I feel like I never really noticed it. It’s mounted upright on the wall by two brackets. One under the body and one higher up, around the neck.

I don’t know much about objects these days. The microwave on the boat is just a microwave. I couldn’t guess how old it is, whether it was cheap or expensive. A pair of shoes is a pair of shoes. Pens and pencils, rubber balls and jackets – they’re like pictures in a children’s book.

But … I know a lot about this guitar. It’s acoustic. It’s concert size. It may be here as decoration, but it’s not cheap. Inlaid mother-of-pearl on the headstock for the logo: GUILD. Yes, an M-20. American made. Nylon strings. There’s a plectrum wedged between the strings at the headstock. The bridge and fingerboard are rosewood, satin finish. Bone nut and saddle. Mahogany body with a sunburst finish.

There’s a flash of lightning, burning the shape of the guitar onto my eyes. I struggle to stand. Then the deck sinks and I make my run. I grab hold of the guitar, to stop myself falling. I hope whichever idiot decorated this boat didn’t bolt it to the wall. After a moment of fiddling with the neck clasp, the guitar tumbles into my arms.

I take my prize back to the baby. I sit, legs complaining at being forced to sit like a four-year-old at nursery. Can I play it? I don’t know. Abigail used to like hearing me play. Maybe Abigail’s baby will like to hear me play as well.

The guitar is out of tune. I pluck the top string a few times and fiddle with the tuning peg. Without having to think about it, I continue up the strings. I hold down a fret of the last string to match it with the sound of the next. A squall of rain on the windows drowns me out for a moment. The guitar sounds grateful to be tuned. I strum with the plectrum and the guitar raises its voice over the storm.

For that strum, the baby stops crying. He opens bloodshot eyes and looks at me. This feels so familiar, but I can’t think of anything to play. My left hand tries to form a chord, but my fingers tangle over one another. Perhaps if I could remember a song, the chords would come. I cast around the room, the rain-streaked windows, the baby, the nightlight. I can’t remember songs about these things. I take things out of my dressing gown pockets. An open packet of sherbet lemons, some balled-up tissues, a piece of folded paper. I unfold it and find it’s a brochure …

IONIAN FISHING TOURS.

That word, Ionian …

I remember a tune. A song called ‘The Child’. I smile at the coincidence. My fingers form the first chord and my hand strums down. Cmaj7. It rings out and again the baby falls silent.

I hum the first note. My voice is thin, but I feel the buzz in my ears as the note from the guitar and the note from my throat rub against each other. I’d forgotten this feeling. How long since I played? How deep is the ocean?

The life behind me is lit through broken cloud. Close to where I stand, everything is in shadow – the nursing home, the last years with my husband, the journey which brought us here. I can see the space but not the detail. Off on the horizon I can see a few acres of golden light, my childhood. Between the light and the shade, there are patches of sun, but most of the land is dark. My life is a mystery to me. Mostly I think about the distance between me and that golden horizon.

But the guitar is in my hands and the sound is in my throat. I’m ready to play again. There’s a roll of thunder but I ignore it. Just a show-off percussionist. I strum the first chord and start to sing.

The song tumbles out of me and the boat tumbles over darkened sea. Though my hands are stiff, though my fingertips sting with the pressure of the strings, though my voice is cracked like an unrosined bow, I feel light. It’s as if, after hobbling around for so long, I tried running and found I could sprint like a teenager.

The sounds ring in the cabin. If I play hard enough, it’s as though I’m driving the storm back. The song is simple. That word, ‘Ionian’, comes back to me. Ionian is a way of playing music. A ‘mode’. A way of spacing the notes apart. And it’s old. Before music became Handel and Beethoven and Charlie Parker, there were modes. As old as the hills, as old as the sea. They were played on instruments with one string, clay pipes and ocarinas, instruments made of animal bone and hollowed turtle shells. I can’t remember the others yet, but I’ll try. I’ll try anything to feel this way again, racing downhill.

The song isn’t long. It would fit onto a single page. So I play it again and again, strumming the chords and humming the melody. Without pausing, I look at the baby. He’s watching me calmly. The storm still beats against our thin shell, the room still races up and down, but his eyes are drooping. I smile at him. He looks at me like he looks at Abigail on her breast. His breaths become long and deep.

Even when he’s asleep, I don’t stop playing. I want to enjoy this a little longer. The dizzy feeling has become almost nice. My bones ache, I’m sore from my salt-stained nightie, but I don’t want to stop. I close my eyes. Perhaps it’s the rolling of the sea, perhaps the reeling repetition of the music, but I’m spinning. Not dizzying but slow, like a gigantic whirlpool. Is the boat swirling? Has someone pulled the plug out of the ocean?

As the light starts to fade, I cling to the guitar like a buoyancy aid and keep playing until, swoosh-swoosh-swoosh, I circle the drain and tumble into darkness, the tune echoing in my ears like falling water.