Читать книгу When the Music Stops… - Joe Heap - Страница 9

2. The Maiden

ОглавлениеI WAKE FROM THE DREAM.

Or I wake from the memory.

Or I return to the present.

I’m not sure which and it doesn’t really matter. For a moment, I feel nothing. Then there’s pain, spreading like ink on blotting paper. I remember I’m not seven but eighty-seven years old. My back hurts. My arse hurts. My wrists and ankles really hurt. I open my eyes and find that I’m not in my cabin. It must be sometime in the day; I’ve had a siesta in the saloon. Reflections of sunlight ripple over the wooden ceiling. That’s strange …

I turn my head to look and my eyes widen. I’m lying on the floor. The floor is covered in water, newspapers and novels strewn around. The guitar is a little way away. The storm comes back to me. A little way from me, in the bouncy chair, I see a small, crumpled body.

I jump up.

Well, my mind jumps up. My body doesn’t follow. I try again. Like a choked engine, my body stays on the floor. Pain stalls me. I have pills for my back which I could take. But they’re all the way downstairs, in my cabin. I fix my eyes on the baby, his bundled body. He has slept there all night, in a wet sleepsuit, in this draughty room. Nobody has come to him.

I try a third time. Slowly, I sit up. I crawl across the room until I reach him. I kneel and put one hand to his chest. The wet fabric is cold. No movement. No breath. His head is slumped into his chest.

‘No, no, no …’

The baby’s head jerks up. He gasps and his eyes flicker. I gasp too, then laugh with relief. My hands fumble with the straps.

‘Oh lovie, come on now …’

I lift the limp weight of him up to my chest. As I hold him, he shivers and cries once. Legs and back protesting, I carry the baby to the sofa and sit with him. He doesn’t cry again, but the shiver returns. I take a blanket and wrap it around us, rubbing his back and kissing his head. The warmth allows his shiver to blossom. It scares me that his tiny body is shaking so hard, as though it might shake apart. At length his blue eyes open, and he picks his head up.

For a minute there is calm in the room. Just me and the baby, looking into each other’s eyes. Then he starts to cry. It’s small at first, but he soon warms to it. Outside, the storm has passed. The saloon has windows on all sides. The sun is beating down over endless ocean. There are no boats or ships, no islands.

‘Abigail?’

It’s silly to call for her, my voice no louder than the baby. If Abigail were able, she would have come already. She must be busy. I swaddle him with the blanket. He kicks, trying to be free. I arrange the cushions so he won’t roll off the sofa.

I bend to pick up Abigail’s novel. It’s been soaked and half-dried in a shaft of sun. The pages are warped and stuck together. I try to smooth it into shape and find it’s not a novel at all.

TEN STRANGE LESSONS

Dispatches from the Frontier of Physics

I wonder what Abigail makes of it. She was a curious child, a question-asker. Like her father, I think, though I don’t remember Abigail’s father at all. I do my best to close the book, but it keeps springing open at the page where it landed in the storm.

I read:

The passage of time is perhaps the clearest, most common-sense aspect of our daily lives. We wake in the morning and go to bed at night. The space in between is obvious to us. But the closer we look, the more ‘time’ seems to disappear. Our newest theories suggest that time itself is an illusion. It is simply not real.

I set the book down. I don’t understand any of it. Wrapping my dressing gown around me, I open the doors onto the deck. I’ve had trouble walking on the boat; my balance isn’t good. Now the ocean is so calm I barely notice it. The varnish is hot and tacky under my bare feet.

‘Abigail?’

All around me the ocean laps at the hull. I put my hands on the railing, queen of all I survey. I don’t like the sea; I never learned to swim. There’s something about not being able to see through the waves to what’s underneath. It’s not just the fear of drowning. It’s the size of the sea, the way it seems to go on forever. It makes me feel small, the opposite of sitting in a room surrounded by chairs, lampshades and yesterday’s newspapers. Those things are there for me. The sea isn’t there for anyone.

I trudge to the back of the boat and look down, trying to remember what’s different about the picture. There’s no white water …

The engine is quiet.

I remember the sound of the engine. Almost musical – a drone-like hum and, under that, a different vibration, a slow thrum-thrum-thrum like a pulse, a bass note that changed tempo depending how fast we were going. Now there is silence, but we’re not in port. I don’t know anything about sailing, but I think the water looks deep.

I turn around to the stairs on the left of the cabin doors and carefully start to climb. I’ve only been up these stairs once, when Abigail wanted to take photographs of me pretending to drive. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was up here, hiding from his responsibilities with the baby, using all those dials and levers and flashing lights as an excuse not to do any real work. I open the door to the cockpit.

‘Hello?’

There is nobody. The engine is off, and the lights are off. I flick a couple of switches. Nothing happens. I hobble back down to the deck. The sun is so strong it could pin me to the deck, and the baby is still crying.

‘Abigail?’

I walk the strip of deck that runs down the side of the saloon, up to the bow of the ship. There is no one here, nothing to see except the glare off the polished wood.

Except, near the railings are a pair of shoes. The laces are still tied, as though someone kicked them off in a hurry. They’re wet, bleeding twin puddles onto the deck. I look at the shoes for a long moment, trying to remember where I’ve seen them before. They are running shoes, neon yellow, the sort a young woman would wear …

But I can’t remember.

I look over the side of the boat to see its name, painted blue on the white hull.

MNEMOSYNE

A memory surfaces of the first time we went to see the boat.

‘How do you pronounce it?’ Abigail had asked, looking at the painted name.

‘Nemmo-sign,’ he said, with confidence.

‘Nem-oss-inny,’ I said at the same moment. He ignored me. I don’t know where that came from.

‘Anyway,’ he went on, ‘I’ll change the name when we get her back to England. Something classic like Discovery.’

Eejit.

I shuffle back down the boat and let myself into the cabin. It’s hot in here. When the engine was running, you could come in from outside and feel the cool air. I close the door and turn to see Rene sitting on the sofa next to the baby, stroking his head. She looks up at the sound.

‘Hello?’

‘Rene? What are you doing here?’

‘I dunno. I just woke up. Who are you?’

‘It’s me, Ella.’ I stare down at Rene’s frown for a long moment. ‘Ella Campbell.’

‘Ella? Naw.’

‘I am, honest.’ I walk over and sit on the sofa, with the baby between us. Rene is still wearing her school uniform – pleated skirt and knee-high socks, white cotton blouse. My friend peers at my face, brows knitting together.

‘Oh aye, it is you, Ellie. You cut your hair short. You look like your nan.’

‘You remember my nan?’

‘She lived in that single-end on Gourlay Street. She made us buttery rollies that one time.’

I haven’t thought of Gourlay Street, my nan, or buttery rollies for a long time. Rene’s reappearance is like looking under a floorboard and finding a biscuit tin of childhood treasures. I have questions, but the baby chooses this moment to make a single, high-pitched cry. It sounds odd, and I realize he must be very hot, wrapped up in that blanket. I unwrap him and hold him in my arms again.

‘Whose wean is that?’

Rene’s accent is stronger than I remember. I hadn’t realized my own had faded in the years since I left Glasgow.

‘He’s my daughter, Abigail’s.’

‘You have a daughter? So, this is your grandson …’ Rene thinks for a moment. ‘What’s his name?’

‘I don’t remember.’

‘You don’t remember your own grandson’s name?’ Rene chuckles.

‘I forget things. That’s what being old is like.’

‘Aye, I suppose.’

The baby is quiet, but his eyes dart around the room desperately. He’s searching for the same person I am.

‘What does it feel like, being old?’ Rene sticks her chin out at me and squints as though trying to puzzle something out. I think for a minute, then say –

‘What does it feel like being young?’ I smile, confident that I’ve said something wise, but Rene isn’t impressed.

‘No, that’s not an answer. I’ve always been young; I don’t know any different. You’ve been young and old, and all the bits in the middle. So, what does it feel like?’ She squints at me. ‘Is it crap?’

I see my friend as an equal, but Rene doesn’t see me the same. I feel like I’m looking from behind a mask. Something grotesque I’ve put on for Halloween and can’t get off.

‘It feels like … it feels like …’ I shake my head in frustration. ‘It feels no different! I feel no different. I’m the same person. You never feel grown up. You just feel like your body has gotten old and creaky and stupid. But you’re the same, inside.’

‘Okay …’ Rene nods at her shoes for a second, thinking. ‘Do you want to play a game?’

* * *

I wake with the baby still in my arms. The sun is on a different side of Mnemosyne now. I don’t know whether the sun has moved, or we have. We played I Spy until I fell asleep. Rene is on the sofa opposite, on her front, trying to read a newspaper. Already this seems normal. I’ve spent a lifetime waiting to turn a corner and see my friend, so it doesn’t seem strange that it’s finally happened.

The baby is still sleeping. What is his name? I must find out; it’s embarrassing not knowing. Abigail was always saying it. These facts haven’t gone anywhere. My doctor explained it like this – all my memories are still there, in my head, but they’ve become like locked rooms. The corridors between them have caved in.

I forget everything my doctor tells me, but I’ve remembered this. A big house, with many rooms in many styles. But now the house has gone to seed, damp has rotted the timbers, the windows leak and mould spots the plaster. If I could get to those locked rooms, I could rescue some trinkets, bring them close to the centre of myself. Even now I have a few dry, tidy rooms, like a down-at-heel aristocrat who can’t afford to fix the mansion.

I look down at the baby. He’s a good boy. I’ll put him in his bouncer while I get some pills. I push us off the sofa as the boat tilts.

‘Y’all right?’ Rene looks up from the paper.

‘Just going to put the baby down.’

‘Ellie, what’s an “internet”?’

I think for a moment, but my understanding of the internet can barely be more than that of a child of 1936.

‘It’s a fishing thing.’

‘Ah, right. Thought so.’

‘I’m just going downstairs.’

‘Okay. See if you can find any games to play.’

Downstairs, the lights are out. The doors to the cabins, where portholes let daylight in, are closed. I feel my way down the last few stairs and gasp. I’d forgotten the ankle-deep water. Some floating thing bumps against my leg and makes me jump. I move forward, feeling against the walls.

I open the first door, the baby’s room. A little light fills the corridor. I can see the object that bumped against my leg was a half-empty water bottle. There is more – a teething toy, shaped like the head of an elephant with flappy fabric ears; several jars and sticks which have escaped a bag of make-up; a blue plastic razor.

Is the water higher than before? It’s hard to judge, when I only felt it in the dark. I move forward until I get to my own room. All the bedsheets are in a sodden mess on the floor. The contents of my bedside table have spilled out, moisturizing creams and incontinence pads cruising around the room like battleships. I wade back into the corridor.

Here I remember – I should let Abigail know about the water. I try the handle of her bedroom and find it unlocked.

‘Abigail? Abigail?’

There is no response, but I wonder if she might be in the bathroom. I sit on the edge of the bed. I want to call his name, just in case he’s the one in the bathroom. But I can’t remember his name, or his face, or where he met Abigail in the first place, and so entered our lives.

The objects on the dresser have been stirred around but haven’t fallen. Only the compact mirror has fallen and shattered. Eventually, I get up and knock on the bathroom door.

‘Hello?’

There’s no reply, so I turn the handle. Empty. I stand there, trying to remember what I know. Where is Abigail? I’m sure I’m being stupid. It doesn’t help that I’m thirsty. Maybe Rene will remember what port we sailed from.

I trudge back around the bed. As I pass, I see something tucked under a pillow in a black case. I pull out a camera and sling it around my neck.

Before I go back up to the main cabin, I look into the room next to Abigail’s. The one they’ve been using as the baby’s playroom. The door opens easily. Water rushes around my ankles, as though there was more water in this room than in the corridor. A sodden teddy bear slides past me, face down. I notice that the wall – curved like the curve of the hull – is dented inward. The wood panelling is splintered. A little water dribbles down, like blood from a graze. Something floating in the water bumps against my leg.

I close and lock the door, then put the key in my pocket. I go back up to the main cabin.

‘You find anything to do?’ Rene kicks her legs back and forth.

‘Not really.’ I almost mention the playroom, but I don’t. ‘I found this camera. Maybe we can look at some pictures.’

‘Y’can’t look at pictures on a camera, Ellie. If y’open the back the film is all spoiled.’

‘This one’s different.’

I sit next to Rene. After some fiddling, the camera turns on and the little screen lights up with a picture of Mnemosyne and a man, arms raised in something like triumph. Rene gasps, mouth forming an ‘O’. I’m pleased to have something fancier than Rene Mauchlen, even if it’s not really mine.

‘Wow, that’s …’ Rene searches for the right word. ‘Braw.’

‘See, you can look through the pictures like this.’

I flick through more pictures of him posing in front of his new boat. I remember now – we came on holiday so that he could buy the boat second-hand. He was going to sail us back to England. What went wrong?

‘Is that your daughter?’

I look at the picture. A family at a restaurant table. On the left is Abigail, smiling brightly, hair tied back in a ponytail. On the right stands him, wearing the look of someone who thinks a stranger is about to drop his expensive camera. In the middle, with the baby on her lap, is a crumpled old woman.

Oh.

That’s me.

‘Here, you play with it.’ I hand the camera to Rene, who folds her legs and bends herself close to the screen. I go over to the baby and stroke his head. He doesn’t stir.

‘Hello, baby.’

I prod him in the ribs. He still doesn’t wake, even as I shake him a little. This isn’t how a baby should look. I lift him into my arms and he’s limp, like a wet rag. I carry him to the sofa and stroke his head, trying to think. There’s a dip, running from one side of his head to the other. This means something, but what? God, I wish I weren’t so old.

Rene comes over, peering at the baby. ‘What’s the matter?’

‘I don’t know … he’s all floppy.’

‘He looks peely-wally. Perhaps he’s tired? Mam says I go floppy like that when I fall asleep next to the radio, and Pa has to carry me through to the next room.’

‘But he was sleeping already.’

‘Perhaps he’s hungry?’ Rene frowns.

‘Yes, maybe. Oh, where’s Abigail?’

‘His mam?’

I nod. ‘She’s the only one who can feed him. But she’s been gone for a while now.’

‘If she’s not around, he must be thirsty.’

‘You look after him for a minute.’

‘Aye, all right.’

I go to the little kitchen at one end of the living room. There’s only enough room for me to stand here, surrounded by the surfaces. I look in the food cupboard first, in case there is baby formula. When Abigail was small, they encouraged you to use formula. Better than breastmilk, they said, fortified with vitamins. Abigail won’t touch the stuff.

I can’t see any here. Tins of beans, a packet of rice – nothing for a little baby to eat. Next, I look in the fridge. The light doesn’t come on and there’s no gust of cool air. There are the leftovers from a meal we had, an unopened pack of that salty Greek cheese Abigail likes, jars of pickles and olives.

Why is there no milk? We’ve had cups of tea and coffee. There are dirty cups in the living room. Abigail was always bringing me cups of tea, even though it meant I always needed the loo. I look in the cupboard under the sink. Here there are bottles of bleach, a dustpan and brush, a clear, green liquid in a squirty bottle, and a pallet of white plastic pots.

Yes – this is it. A quarter of the UHT milk pots have been used. One by one I rip the foil lids off the pots. I make a mess of screwing the parts of the bottle together. I take it all apart again and put the teat in the right way around. Finally, it’s ready. I rush back through to the living room. The baby is unmoving.

Rene is stroking his head, unconcerned. She leans over him with the interest of one child in another. ‘This is where I was’ if they are older, ‘this is where I will be’ if they are younger, looking for clues to the mystery of their existence. My breath is fast; I can’t calm myself. I sit down and pick up the unmoving baby, push the teat past his lips. He does not suck. The bottle just sits in his mouth. His eyes flutter for a second but nothing more. He looks dead.

‘Come on, baby. Have a drink. You’ll feel better.’

I take the bottle out of his mouth, put it back again. I pinch his cheek, bob him up and down. Nothing. I used to know how to get babies to drink. I put the bottle back in and, as I sit in that position, a memory surfaces. The baby is a different baby. Baby Abigail. I remember. I tilt the bottle down, toward his chest, so the teat is pressed against the roof of his mouth. I rub it from side to side. Without opening his eyes, his lips seal around the bottle and he starts to suck.

‘Oh good,’ Rene says matter-of-factly. She gets up on her knees so she can stare out of the window at the sea. I don’t dare move as he takes the bottle. At first it’s slow, just one suck every five seconds or so. But it becomes faster, more urgent. A minute passes.

‘I wish I’d had a baby.’

Rene watches the waves. She looks calm, but her jaw is clenched. I feel sick, but I should be brave in return.

‘I’m sorry you’re dead.’

Rene shrugs once and flops down on the sofa, fiddling with the buttons on her blouse.

‘S’all right. It’s not so bad. I just wish I’d had time to do more stuff.’

‘We can do stuff now.’

She nods sulkily. ‘What happened, after I died?’

I’m about to say I don’t remember, then realize this would be rude. I try to remember. ‘Everyone was upset. The whole school. All our year came to sing at the church.’

‘And Mam? And Pa?’

‘Of course.’

‘And Robert?’

It takes me a moment to remember Robert as he was to Rene. Nine years to our seven, skinny and quiet.

‘He was there.’

‘Was he all right, without me?’

‘I think he was angry.’

‘At who?’

‘At everyone. At me.’

‘Why you?’ Rene looks at me, puzzled.

‘Because … because I kept you out in the cold. In Paddy’s Park all those hours while you coughed.’

‘Nah.’ Rene shrugs. ‘It would still have happened. My lungs were bad. Springburn has all those smoky factories.’

‘Well, I felt bad.’

‘Y’shouldn’t have. Did Robert forgive you?’

‘I think so …’ I change the subject. ‘Are you hungry?’

Rene shakes her head.

‘Not any more.’

There’s a sucking sound – the bottle is empty. Rene comes to the kitchen with me and puzzles over the empty cartons, sniffing one suspiciously. By the time I get back to the sofa the baby has his eyes open. When I put the bottle to his mouth, he thrashes his head and tries to swipe it out of my hand. He succeeds on the third try and it rolls with the tilt of Mnemosyne to the far side of the room. He wails with gusto.

‘You should sing him a lullaby,’ Rene says, helpfully.

‘I can’t think of one.’

I go downstairs to find the nappy bag and a change of clothes. I pause at the top of the stairs, heart pounding. I mustn’t stop. The baby grow is difficult. Even when it’s done there are spare poppers and bits of fabric are bunched up, but he’s dressed and clean.

It doesn’t fix the crying.

For five minutes I stop, leaving him with Rene. I drink a glass of tepid tap water and eat chicken in white sauce from the tin. I take tablets for my back. I know there are other tablets I should be taking, but Abigail is the one who doles them out in my weekly organizer.

Still the baby cries.

Using cushions and a blanket from the sofa, I make a sort of crib on the floor, enough that I know he won’t roll away. The water has dried in the sun by now. I put him down; I need to think. Thinking is hard enough, but with the constant wailing it’s impossible. Rene is sitting on the sofa with a guitar in her lap. I’d forgotten about it until now. She is struggling to reach the frets with one hand and get her other arm over the body.

‘This one’s bigger than mine …’ She plays a few wobbly notes, the beginnings of ‘Frère Jacques’, then gives up. ‘Can you play?’

‘Perhaps, a little.’

‘You should play us something. The baby might like it.’

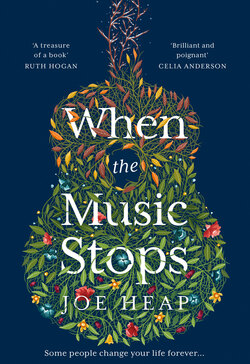

I take the guitar. I don’t want to admit I can’t remember any songs. I can’t even remember the one I played last night. But there are others like that one. Seven of them.

I remember a line from somewhere … The seven ancient modes are not scales in the true sense. They do not specify particular notes. Rather, they are patterns, spacing the notes we can play closer or further apart like the notches on a key. And that is what the modes are – seven keys to this earlier music.

With that, I remember the second song. I sit on the sofa, position the guitar while Rene scoots closer, and start to play. The opening bars see-saw between A minor and B minor. The tune I’m humming rises and falls gently like waves.

The baby stops crying. He watches us, me playing and Rene pressed into my side. I reach the end of the tune and circle back to the beginning, closing my eyes.

‘When did you get so good?’

I ignore Rene’s question. I have a familiar feeling. We are going down. The sea is draining, like water in a lock. It feels like being in a descending lift. It gets stronger as I play, until I daren’t stop playing.

Down, down, down, into darkness.