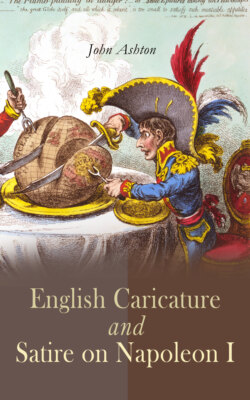

Читать книгу English Caricature and Satire on Napoleon I - John Ashton - Страница 10

CHAPTER VI.

ОглавлениеJOSEPHINE’S DRESS AND PERSONAL APPEARANCE—HER REPUTED CONNECTION WITH BARRAS—MARRIAGE WITH NAPOLEON—HER TASTES AND DISPOSITION.

Let us for a moment, as an antidote to the caricaturist’s pictures, see what was Josephine’s dress at this period.26 ‘Here is Madame de Beauharnais, that excellent Josephine, whose heart is not made for coquetry, but who throws a childish joy into her dress. With an air less dramatic and superb than her rivals,27 the joyous and kindly creole is, perhaps, the most French of the three, Madame Tallien is the most Greek, and Madame Viconti the most Roman. Josephine wears a wavy dress, rose and white from top to bottom, with a train trimmed at the bottom with black bugles, a bodice six fingers deep, and wearing no fichu; short sleeves of black gauze, long gloves covering the elbow of noisette colour, which suits this beautiful violet so well; shoes of yellow morocco; white stockings with green clocks. If her hair is dressed after the Etruscan manner, ornamented with cherry-coloured ribbons, I am sure it is impossible to approach nearer to the antique. To tempt the fashion is the sole ambition of the pretty Josephine, but it happens that the celebrated Madame de Beauharnais sets it.’

It is impossible to quit this subject without some contemporary quotations, as they help us to realise the truth, or falsehood, of the caricaturist.28 ‘Madame Tallien was kind and obliging, but such is the effect on the multitude of a name that bears a stain, that her cause was never separated from that of her husband. The following is a proof of this. Junot was the bearer of the second flags, which were sent from the army of Italy to the Directory. He was received with all the pomp which attended the reception of Marmont, who was the bearer of the first colours. Madame Bonaparte, who had not yet set out to join Napoleon, wished to witness the ceremony; and, on the day appointed for the reception of Junot she repaired to the Directory, accompanied by Madame Tallien. They lived at that time in great intimacy; the latter was a fraction of the Directorial royalty with which Josephine, when Madame Beauharnais, and, indeed, after she became Madame Bonaparte, was in some degree invested. Madame Bonaparte was still a fine woman; her teeth, it is true, were already frightfully decayed, but when her mouth was closed she looked, especially at a little distance, both young and pretty. As to Madame Tallien, she was then in the full bloom of her beauty. Both were dressed in the antique style, which was then the prevailing fashion, and with as much of richness and ornament as were suitable to morning costume. When the reception was ended, and they were about to leave the Directory, it may be presumed that Junot was not a little proud to offer to escort these two charming women. Junot was then a handsome young man of five and twenty, and he had the military look and style for which, indeed, he was always remarkable. A splendid uniform of a colonel of huzzars set off his fine figure to the utmost advantage. When the ceremony was ended, he offered one arm to Madame Bonaparte, who as his general’s wife was entitled to the first honour, especially on that solemn day; and offering his other arm to Madame Tallien, he conducted them down the staircase of the Luxembourg. The crowd stepped forward to see them as they passed along. “That is the general’s wife,” said one. “That is his aide de camp,” said another. “He is very young.” “She is very pretty.—Vive le General Bonaparte!—Vive la Citoyenne Bonaparte! She is a good friend to the poor.” “Ah!” exclaimed a great fat market woman, “She is Notre Dame des Victoires!” “You are right,” said another, “and see who is on the other side of the officer; that is Notre Dame de Septembre!” This was severe and it was also unjust.’

We must not trust to the caricaturist’s portrait of Josephine. She was good looking and graceful then, but, afterwards, she did become very stout. We must never forget in looking over the folios of caricatures of this period, that the idea of caricaturing then was to exaggerate everything, and make it grotesque; it is only of modern years that the refinement of a Leech, Tenniel, or Proctor, gives us caricature without vulgarity.

After seeing Josephine as she really was, it will be worth while to compare the satirist’s idea of her, and her marriage with Napoleon.

Nap changed on entering Society,

Obscurity for notoriety;

He to Barras only inferior,

Commands the army of th’ interior.

As pride in office is essential,

His manners now were consequential;

Conducting all affairs of weight,

The little man was very great;

And by this sudden rise to dignity,

He gave full weight to his malignity.

Barras, now moved by his persuasions,

Consulted him on all occasions;

A greater compliment, too, paid he,

He got for him, a cast off lady: A widow rich, as they relate, But how so rich, ’tis hard to state, Her spouse, for politics reputed, By Robespierre was executed, And she was by Barras protected, Till he at length the fair neglected. However, she procured with great art, A man of colour for a sweetheart; By which no fortune’s manifested, For men of colour are detested; They married would have been, moreover, But that—in stepped another lover;

* * * * *

* * * * *

There are some writers who pretend,

The lady’s virtue to defend;

For, in the character they draw,

She’s guilty of but one faux pas; But others, probably censorious, Declare her lapses were notorious, And that, devoid of sense and shame, She even gloried in the same; So reckoning all things, the amount is, She was a condescending countess. The lady was, as it appears, Older than Nap by twenty years; But, for a man, who scorned to prove The votary or slave of love— Whispering soft nonsense, and such stuff— She certainly was good enough. Short, like himself, and rather bulky, But not so insolent and sulky. As by Barras, too, recommended (No matter from what stock descended), It certainly must be allow’d Of such a wife he should be proud. So, locked together, soon were seen, Brave Boney and fair Josephine.

The pictorial caricaturist, Gillray, gives us February 20, 1805, ‘Ci-devant occupations, or Madame Tallien, and the Empress Josephine Dancing Naked before Barras, in the Winter of 1797—a fact.’29

At the foot of this etching, which depicts the sensual bon viveur, Barras, looking on at the lascivious dancing of his two mistresses, Madame Tallien and Josephine, it says: ‘Barras (then in power), being tired of Josephine, promised Bonaparte a promotion, on condition that he would take her off his hands. Barras had, as usual, drank freely, and placed Bonaparte behind a screen, while he amused himself with these two ladies, who were then his humble dependents. Madame Tallien is a beautiful woman, tall and elegant. Josephine is smaller, and thin, with bad teeth something like cloves. It is needless to add that Bonaparte accepted the promotion, and the lady, now Empress of France!’

Barre, who notoriously wrote against Napoleon, says:30 ‘And not satisfied by procuring him a splendid appointment, he made him marry his mistress, the Countess de Beauharnais, a rich widow, with several children; and who, although about twenty years older than Bonaparte, was a very valuable acquisition to a young man without any fortune. The reputation of the Countess de Beauharnais was well established, even before the Revolution: but Buonaparte had not the least right to find fault with a woman presented to him by Barras.’

At all events they were married, and here is G. Cruikshank’s idea of the ceremony, and here, also, he depicts the bridesmaids and groomsmen.

Their honeymoon was of the shortest, for De Bourrienne says: ‘He remained in Paris only ten days after his marriage, which took place on the 9th of March, 1796. Madame Bonaparte possessed personal graces and many good qualities. I am convinced that all who were acquainted with her must have felt bound to speak well of her; to few, indeed, did she ever give cause for complaint. Benevolence was natural to her, but she was not always prudent in its exercise. Hence her protection was often extended to persons who did not deserve it. Her taste for splendour and expense was excessive. This proneness to luxury became a habit which seemed constantly indulged without any motive. What scenes have I not witnessed when the moment for paying the tradesmen’s bills arrived! She always kept back one half of their claims, and the discovery of this exposed her to new reproaches. How many tears did she shed, which might easily have been spared!’

We here see the caricaturist’s idea of Josephine as a French general’s wife.

A GENERAL’S LADY.