Читать книгу English Caricature and Satire on Napoleon I - John Ashton - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER XVII.

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

THE OLD RÉGIME AND THE REPUBLICANS—THE ‘INCROYABLES’—NAPOLEON LEAVES EGYPT—HIS REASONS FOR SO DOING—FEELING OF THE ARMY—ACCUSED OF TAKING WITH HIM THE MILITARY CHEST.

It is refreshing, and like going among green pastures and cool streams, to leave for a while political caricature, with its ambitions, and its carnage, and find a really funny social skit, aiming at the follies of the times, even if it be only in ridiculing extravagance in dress.

Exceedingly droll is a social caricature by Gillray (August 15, 1799), where a courtly old gentleman of the Court of Louis XVI. bows low, saying, ‘Je suis votre tres humble serviteur,’ whilst the ruffianly French ‘gentleman of the Court of Égalité’ replies with a sentence unfit for reproduction. (See next page.)

Littré, in his magnificent dictionary, gives a very terse definition of these ‘Incroyables’: ‘S. m. Nom donné aux petit maîtres sous le Directoire, parce q’uon les entendait s’ecrier propos, c’est vraiment incroyable; et, parce que leur costume était tellement exagéré qu’il dépassait la croyance commune.’ They were Napoleon’s detestation, according to Madame Junot, and she describes them with feminine minuteness. ‘They wore grey greatcoats with black collars and green cravats. Their hair, instead of being à la Titus, which was the prevailing fashion of the day, was powdered, plaited, and turned up with a comb, while on each side of the face hung two long curls, called dog’s ears (oreilles de chien). As these young men were very frequently attacked, they carried about with them large sticks, which were not always weapons of defence; for the frays which arose in Paris at that time were often provoked by them.’

Pardon must be begged for this digression, and the matter in hand strictly attended to.

A FRENCH GENTLEMAN OF THE

COURT OF LOUIS XVI.

A FRENCH GENTLEMAN OF THE

COURT OF ÉGALITÉ.

Napoleon left Egypt on August 23, 1799, and reached France October 8 of that year. The causes for this step will be detailed a little later on. Meanwhile the caricaturist was watching events on the Continent, and, after his lights, depicting them. With those not personally affecting Napoleon we have nothing to do; and of him—Egypt being a far cry—we have but few, until after his return, when he was brought prominently before European notice. Gillray thought he saw his power declining, and on September 1, 1799, he published ‘Allied Powers, Unbooting Égalité.’ In this picture Napoleon is being badly treated. One foot is on a Dutch cheese, which a Hollander is plucking away; a British tar has him fast round the waist, and arms; whilst a Turk, of most ferocious description, his dress being garnished with human ears, is pulling his nose, and slashing him with his scimitar, St. Jean d’Acre, which is reeking with blood. Prussia, backed up by Russia, is drawing off Italy, which serves as a boot for one leg, and, with it, a large quantity of gold coin.

The causes which induced Napoleon to leave Egypt cannot better be made known, and understood, than by quoting from De Bourrienne, who was an actor in this episode. He says: ‘After the battle,49 which took place on the 25th July, Bonaparte sent a flag of truce on board the English Admiral’s ship. Our intercourse was full of politeness, such as might be expected in the communications of the people of two civilised nations. The English Admiral gave the flag of truce some presents, in exchange for some we sent, and, likewise, a copy of the French Gazette of Francfort, dated 10th June, 1799.50 For ten months we had received no news from France. Bonaparte glanced over this journal with an eagerness which may easily be conceived.

‘ “Heavens!” said he to me, “my presentiment is verified: the fools have lost Italy. All the fruits of our victories are gone! I must leave Egypt!”

‘He sent for Berthier, to whom he communicated the news, adding that things were going on very badly in France—that he wished to return home—that he (Berthier) should go along with him, and that, for the present, only he, Gantheaume, and I, were in the secret. He recommended him to be prudent, not to betray any symptoms of joy, nor to purchase, or sell, anything.

‘He concluded by assuring him that he depended on him. “I can answer,” said he, “for myself and Bourrienne.” Berthier promised to be secret, and he kept his word. He had had enough of Egypt, and he so ardently longed to return to France, that there was little reason to fear he would disappoint himself by any indiscretion.

‘Gantheaume arrived, and Bonaparte gave him orders to fit out the two frigates, the Muiron and the Carrère, and the two small vessels, the Revanche and the Fortune, with a two months’ supply of provisions for from four, to five, hundred men. He enjoined his secrecy as to the object of these preparations, and desired him to act with such circumspection that the English cruisers might have no knowledge of what was going on. He afterwards arranged with Gantheaume the course he wished to take. Nothing escaped his attention.’

Bonaparte concealed his operations with much care; but still some vague rumours crept abroad. General Dugua, the commandant of Cairo, whom he had just left, for the purpose of embarking, wrote to him on August 18 to the following effect:—

‘I have this moment heard, that it is reported at the Institute, you are about to return for France, taking with you Monge, Berthollet, Berthier, Lannes, and Murat. This news has spread like lightning through the city, and I should not be at all surprised if it produced an unfavourable effect, which, however, I hope you will obviate.’

Bonaparte embarked five days after the receipt of Dugua’s letter; and, as may be supposed, without replying to it.

On August 18, he wrote to the Divan of Cairo as follows: ‘I set out to-morrow for Menouf, from whence I intend to make various excursions to the Delta, in order that I may, myself, witness the acts of oppression which are committed there, and to acquire some knowledge of the people.’

He told the army but half the truth: ‘The news from Europe,’ said he, ‘has determined me to proceed to France. I leave the command of the army to General Kleber. The army shall hear from me forthwith. At present I can say no more. It costs me much pain to quit troops to whom I am so strongly attached. But my absence will be but temporary, and the general I leave in command has the confidence of the government, as well as mine.’

At night, in the dark, on August 23, he stole on board: and who can wonder if the army expressed some dissatisfaction at his leaving them in the lurch? From the many works I have consulted, whilst writing this book, I can believe the words of General Danican (who has been before quoted) in ‘Ring the Alarum Bell!’—‘Immediately after Buonaparte’s midnight flight from Egypt, with the Cash of the army, he was hung in effigy by the Soldiers; who, in dancing round the spectacle, sang the coarsest couplets (a copy of which I have now in my possession) written for the occasion, to the tune of the Carmagnole, beginning: “So, Harlequin has at length deserted us!—never mind my boys, never mind; he will at last be really hanged; he promised to make us all rich; but, instead, he has robbed all the cash himself, and now’s gone off: oh! the scoundrel Harlequin, &c., &c.” ’

FLIGHT FROM EGYPT.

This charge against Napoleon, of running away with the treasure-chests, is, like almost all the others, of French origin. Hear what Madame Junot says, as it shows the feeling of the French army on this point, that some one had taken them (for Napoleon’s benefit): ‘A report was circulated in the army that Junot was carrying away the treasures found in the pyramids by the General in Chief. He could not carry them away himself’ (such was the language held to the soldiers), ‘and so the man who possesses all his confidence is now taking them to him.’ The matter was carried so far that several subalterns, and soldiers, proceeded to the shore, and some of them went on board the merchantman which was to sail with Junot the same evening. They rummaged about, but found nothing; at length they came to a prodigious chest, which ten men could not move, between decks, “Here is the treasure!” cried the soldiers; “here is our pay that has been kept from us above a year; where is the key?” Junot’s valet, an honest German, shouted to them in vain, with all his might, that the chest did not belong to his chenerâl. They would not listen to him.

‘Unluckily, Junot, who was not to embark till evening, was not then on board. The mutineers seized a hatchet, and began to cut away at the chest, which they would soon have broken up, had not the ship’s carpenter come running out of breath. “What the devil are you at?” cried he, “mad fellows that you are: stop! don’t destroy my chest—here’s the key.” He opened it immediately, and lo!—the tools of the master carpenter.’

Barre, of course, alludes to this alleged robbery, and Combe writes of his desertion of his troops as follows:—

Aboukir castle having won,

Our hero thought it best to run.

The bravest man will run away,

When it is dangerous to stay;

But, as he to his troops declared,

By him all dangers should be shared,

And that on no account he’d leave them,

’Twas proper he should now deceive them.

The cunning he display’d in fight,

He manifested in his flight.

On some pretence, it seems, he wrote

To certain generals a note,

Acquainting them with what he wanted,

The time and place, too, he appointed.

These generals, so well they fared,

The fame of his desertion shared. When to th’ appointed place they got, Nap was already on the spot; And, what of all things made them glad, The military chest he had! He left his army—but we find He left these words for them behind: ‘This parting grieves me sore, altho’ meant To be for only a short moment.’

BUONAPARTE LEAVING EGYPT.

For an Illustration of the above see the intercepted Letters from the Republican General Kleber to the French Directory respecting the Courage, Honor, and Patriotism of——, the Deserter of the Army of Egypt.

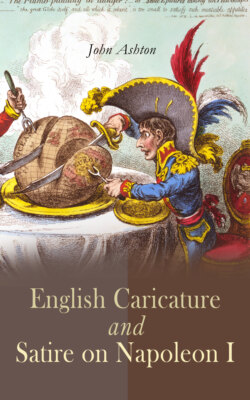

This caricature is presumably by Gillray, although it is not signed by him; and, as it was published on March 8, 1800, it is absolutely prophetic, for Napoleon is pointing to a future imperial crown and sceptre. This is especially curious, as it shows how, even then, the public opinion of England (of which, of course, the caricaturist was but a reflex) estimated him.