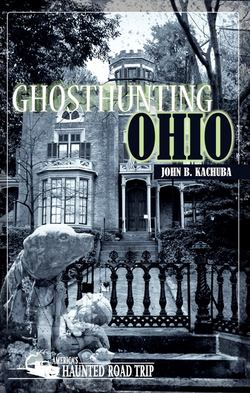

Читать книгу Ghosthunting Ohio - John B. Kachuba - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLudwig Mill

GRAND RAPIDS

SOME PEOPLE NEVER REALLY RETIRE FROM THEIR JOBS. It is difficult for them to accept the fact that, after being on the job for years and years, their services are no longer required. With no other activities to fall back on they work vicariously, gleaning the latest gossip from the guys down at the plant, listening for the familiar noonday whistle to blow, or watching Engine No. 8 roll through the crossing every afternoon precisely at three o’clock, just as it did when they were on the job.

Perhaps these people return to work in the afterlife. Maybe some of them have come back to Ludwig Mill.

I experienced a vision straight out of the nineteenth century the day Mary and I visited Ludwig Mill in Grand Rapids, along the Maumee River. The Volunteer, a blunt-nosed canal boat, was making its slow progress through the massive stone Lock 44 of the canal adjacent to the mill. A tandem team of dusty mules walked the towpath, straining at the line tethering them to the boat, long ears twitching off bothersome flies. A young woman in a bonnet and ankle-length gingham dress stood upon the flat roof of the boat’s cabin, over the bow, watching out for obstacles in the narrow canal. Every so often she would turn around to sass a young man in suspenders and a straw hat who stood in the stern complaining loudly in a German-accented voice that canal boating was no kind of work for a woman.

It was 1846 all over again, the year Isaac Ludwig constructed his mill between the bank of the Maumee River and the mosquito-filled trench known as the Miami and Erie Canal.

But it wasn’t really 1846, as the arrival of two men in a golf cart filled with sacks of flour proved. We watched the canal boat and its crew of young re-enactors drift out of sight.

The Ludwig Mill and the canal operation are all that is left of the town of Providence, a once bustling and brawling little nineteenth-century burg that was wiped out by fire and cholera. Ludwig Mill is the last of hundreds of mills that once lined the endless miles of canals snaking throughout Ohio, connecting Lake Erie with the Ohio and, eventually, Mississippi rivers and linking distant points within the state through numerous cross canals. The mill is still in operation, using waterpower to mill lumber and grain. Along with the reconstructed Lock 44 and a mile of canal, the mill comprises the Providence Metropark on US24, a mile east of SR578.

The mill itself is an imposing sight, standing tall alongside the river, the Prussian blue clapboards and black metal roof partly shaded by a stand of hickories at the river’s edge. At one end of the mill a squarish cupola soars above the trees, the name Ludwig Mill proudly emblazoned in black letters across one side.

It was gloomy inside the mill, and cool. We were the only visitors, our footsteps echoing on the worn wooden floorboards. The interior of the mill was dotted with thick wooden support posts, worn smooth over the years. Hand-hewn beams ran overhead. I saw a set of stairs and catwalks zigzagging back and forth above us, climbing through the upper levels of the mill. The antique framework surrounding us made me feel like Jonah caged in by whale ribs.

There was equipment everywhere, great hulking machines, most of which I could not identify, standing like silent beasts in the dusty air. I did recognize a buzz saw, just like the kind you would see in a Roadrunner and Wyle E. Coyote cartoon, and a large millstone for grinding corn and other grain.

I heard water running somewhere beneath us. We followed the sound and descended into the lower depths of the mill. There we stood upon an iron grate, watching the river rushing below our feet. It was a strong current, but even so, it was difficult to believe that it could generate enough power to run the saws and grinding wheels above us.

We came back up and, while Mary explored one section of the mill, I stepped into the mill office. A wooden rail with a swinging gate separated the business end of the office from the tiny reception area. Just beyond the railing stood a pot-bellied stove, a small table, a couple of wood file cabinets, and a beautiful roll-top desk. Framed black-and-white photos of the mill and various strangers hung on the wall near the door.

“Good morning.”

The disembodied voice startled me until I noticed the person sitting in the desk chair, now pushed back from behind the desk so I could see her.

“Hello,” I said.

She was a young woman, short and sturdily built. She wore dark woolen pants with suspenders and a blue work shirt. Her hair was tucked up under a floppy mill hat, the kind old-time newsboys used to wear. Her name was Becki Braley, and despite her sudden appearance, she was not a ghost. She was a mill technician and she knew how to operate all the equipment in the mill. I was duly impressed, as I had only recently learned how to program my VCR.

Becki told me she had always been interested in history, especially industrial history, so working as a volunteer at the mill was right up her alley. She showed me around the mill, pointing out various machines and explaining how they worked. Mary met up with us.

My wife is not a professional ghosthunter. She is, in fact, an expert and consultant in the field of occupational safety and health, so she listened intently to Becki’s patter.

“Any gruesome deaths?” Mary asked.

“Gruesome deaths?” Becki said.

“You know, anyone pulled into the buzz saw, drowned in the millrace, crushed under a millstone?”

I love it when she talks shop.

Becki said no. The only casualties she knew of were workers getting sawdust in their eyes. I had to admit that could be irritating.

“So no ghosts, then,” I said.

“I didn’t say that,” said Becki. “I’ve seen a ghost here, and so has another girl. One day I was working in the mill alone. I was standing right over there,” she said, pointing to a tight space in front of an old boiler or generator or something. I didn’t know what it was, but it was big.

“I heard footsteps and someone walking behind me,” she said. “I turned, surprised because no one else was here, and caught a glimpse of a large man wearing old-fashioned work clothes. Dark pants with suspenders, light-colored shirt, and a straw hat. Then he was gone. I went outside and checked with the canal boat people to see if any one of them had been in the mill. They hadn’t, nor had any of them seen the man.”

“Who do you think it was?” I asked.

Becki led us back into the office and leafed through a history of the mill written by a local historian.

“I’m not certain,” Becki said, “but I have a feeling it was Frank Heising.”

She showed us a photo of Heising in the book. He was a large man with a big square face.

“He managed the mill from 1919 to 1937. He stood over six feet tall, weighed 250 pounds, and was able to lift a 125-pound bag of grain three feet off the ground with one hand. That’s why I think it was him. The guy I saw was a big man.”

“What about the other ghost?” Mary asked.

“That was different,” Becki said. “It was a child, a little boy most likely. My friend, who was working alone, said she heard footsteps and saw little legs wearing knee-high stockings and knickers run up the stairs. Thinking he was the child of a tourist, she went up the stairs to make sure the boy was okay, but there was no one there. Just as in my story, no one else had seen the child.”

Becki wasn’t certain, but she thought that Frank Heising had had a son. Were both of them still busy working at Ludwig Mill? Like ghost father, like ghost son?