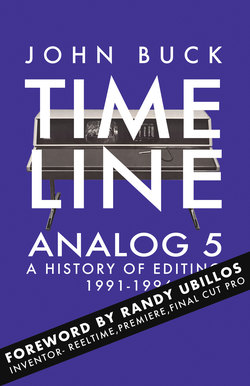

Читать книгу Timeline Analog 5 - John Buck - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FAST

ОглавлениеIn March 1992 Markus Weber finished his PhD and was looking for a job in a tough employment market. He landed an interview at FAST Electronik on Landsberger Strasse in Munich.

I managed to get an interview with Matthias Zahn's second in charge, Ali Adelstein the next evening, followed by signing a contract half an hour later. Matthias and Ali had been hanging out with a mutual friend, who was a cameraman and editor, a couple of weeks earlier.

Bradley Giotes adds:

Martin Leckert, a friend of Matthias, was a professional camera operator in Germany. He bought some consumer video equipment to try to do his own editing at home and became very frustrated. He called Matthias and begged him to create something better.

Fast had sold more than 10,000 Screen Machine digitizer cards in Europe. Weber continues:

They were talking about ScreenMachine and they came across the idea of sticking two ScreenMachines into a computer, hook them up to another chip on a third board, mix the two images of the frame grabbers together and feed the result to a Video Out.

Matthias did a rudimentary drawing on a napkin, and the next day set out to put the idea to the test. This was the birthday of VideoMachine.

The FAST team managed to put together a basic VideoMachine (VM) prototype to demonstrate at CeBit, Europe’s biggest consumer electronics show. Weber recalls the opinions they received.

People wanted an entire application that would replicate an online video editing system on a PC for a fraction of the cost of say a traditional Sony BVE-9000 or CMX-3400. When the team got back to Munich from the CeBit show in Hanover, all hell started to break loose.

Everyone recognized that here was a really huge business opportunity if we could pull clear in the editing app, and this signalled the instant death of my job building the database. You could not expect to go to market without offering some kind of device control to drive two playback VTRs and a third recorder, essentially an Edit Controller.

They needed someone who could be expected to properly deal and model the complex dynamics and ballistics of an intricate mechanical system called a VTR, and devise a system to sync them to an output device. To be clear: no one had any knowledge of video technology beyond what was required for a frame grabber.

To call us video virgins would essentially be overstating the fact. We had absolutely no clue what we were getting ourselves into.

Weber was charged with coming up with a software solution to the edit controller issue, while the rest of the team was setting out to develop an editing system on top of this. He recalls:

Everyone was charged on adrenaline and went into hyperactive mode.

The CeBit reaction convinced Matthias Zahn to continue to the next level, but on two platforms. He created a team for the PC development, and partnered with another Cinetic of Karlsruhe to make a Macintosh version.

Weber recalls:

Both FAST and Cinetic were deeply rooted in the German market, and then the European market. This was the home-base, where the money came from. The Mac was a definite no-show in Europe and mostly still is.

On the other side, the market was comparatively small, when compared to the potential the US represented. So everyone in Europe knew exactly where the future was, and everyone was struggling to get into this market.

This market was dominantly Mac at the time, with the PC a distant runner-up. If you wanted to work both markets successfully, you needed a solution that could survive in both markets, Europe and the US, and this, in turn, meant having an ISA and a NuBus solution.

Of course, it also meant, to close the circle, that in Europe the emphasis was showing that things worked on ISA (you could show the Mac, but no-one really cared), while in the US you had to showcase the Mac.

FAST had three deadlines to meet for the Video Machine.

Ali Adelstein, Markus Duerr, Michael Berneis, Christian Rogg, Martin Regen and Weber needed to prepare for spring COMDEX, followed by the International Broadcasting Convention (IBC) in Amsterdam and then NAB in Las Vegas. Weber continues:

VideoMachine was kind of a super strange beast in more than one aspect and Fast was trying to cover all bases for an uncertain future. In 1992 the PC race was still more than open, and the Mac seemed to be far better suited to video processing than the Windows 3.1 PC and it was.

As it was unclear who was going to win, Fast developed a hardware architecture that was adapted to two platforms: The ISA bus on the PC and the NuBus on the Mac. That was a rather drastic difference in terms of what could be done in principle.

The PC version used the ISA bus concept, which in 1992 was already ageing. It was either 8 or 16-bit wide, ran at 8MHz and typical average transfer rates achievable were 1-2MB/s.

EISA was just about to be introduced, but it was physically and developmentally much more demanding and did not promise to be a successful contender compared to ISA (much higher costs, little revenue benefit), because the innovation-advantage was not perceived as large enough to completely redevelop a hardware solution.

The situation on the PC-side would essentially not change until PCI was introduced. The NuBus, by comparison, already sported a 32-bit interface that could average 10 to 20MB/s throughput in it's original version (10MHz). To be clear, that was about 10 times what ISA could do. So the playing field was anything but level.

For the PC version this meant that over the lifetime of VideoMachine, development was always at least one step behind the Mac version, due to the bandwidth limitation. Weber and the VM engineers had to come up with ingenious ways to overcome the disadvantage and try to draw even with the Mac.

For the Mac development much of the stuff that got developed, like the on-screen timecode display, was simply "render it on the CPU, blast it to the video memory, done".

Zahn registered Fast Electronics U.S. and rushed to deliver a product for IBC then NAB.

As IBC approached we formulated our goal: To be perceived as a valid contender we had to show just one successful A/B roll edit during the press conference, be frame accurate, just once, not drop any frame during the transition effect and then play the recorded result back from the recorder to prove we could do it.

Matthias and Ali stayed in Munich until the last possible minute the evening before the press conference. So far our success rate was low, really low. Typically we would crash to a blue screen halfway through the transition.

The FAST team set up on the show floor of the Amsterdam RAI Exhibition and Congress Centre to program and prepare a “demo script” to emulate a working VM.

Matthias and Ali set out with the latest software (no Internet, you had to copy this to 3.5’’ disk and physically take it with you) and headed straight to the press conference. We bagged it. We made one successful edit, of course we crashed at the end, but the computer screen was not shown and the video monitor showed the output of the recorder, so no one noticed that actually we had failed.

The applause must have been deafening, we had proved we could do it. We immediately started to get flooded with orders. This truly was VideoMachine’s birthday.

The next day everyone at the office was running around the office, wearing a huge constant grin in the face and a T-shirt with the newly developed VideoMachine logo and the simple statement “I am the one and only.”

Two days after the IBC demonstration, the FAST team crashed from exhaustion. When they resurfaced, the NAB conference beckoned.

We headed out to Las Vegas and NAB to conquer the American market.

Laser discs had promised much in the Eighties to create 'film like' non-linear access to rushes. In January 1992, Pioneer demonstrated the breakthrough VDR-V1000 LaserRecorder at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. 'The LA Times' reported:

The unit, the first laser recorder on the market, obviously is not aimed at the average consumer. "We just wanted to show the public how the technology in this area is advancing," said Mike Fidler, senior vice president of home electronics marketing for Pioneer.

The device sold for $39,950 and each disc was $1,295. Meanwhile far from from Pioneer's CES booth, the Texan company Sundance prepared the Quicksilver video editing software for NAB. Principal Rush Beesley recalls:

When we were demonstrating this system, a young and very progressive TV station Chief Engineer, David Gray from KESQ-TV in Palm Springs, saw the presentation and offered us a ‘sea-changing’ proposition. Pioneer had just released a two-headed laser disc recorder/player that used the two heads for random access, “non-linear” playback.

He said he’d provide us with two of those machines for testing if we could interface our editing software to control them. His ideas were to get completely away from tape as a playback medium and use real-time digital playback for inserting commercials in his tape-based long-form programming.

Beesley delivered a working prototype that utilized multiple Pioneer VDR-1000 re-recordable laser disk machines controlled by spot insertion software running on a Macintosh SE computer.

Prior to that the industry adopted Sony Betacart machines preceded by Ampex’s ACR-25 TV spot playback.

Sundance followed with a new version of the Quicksilver editing system. Billboard's review:

The ability to spend less than $5,000 for an A/B roll suite where student interns could easily learn to edit led Aloha, Oregon's Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue Service, to order a Mac Classic II and Sundance video-editing software from Sundance Technology Group of Irving, Texas, for its 6-year-old S-VHS studio.

Aloha's studio fed a closed-circuit channel communicating via INET (Institutional Network system) to fire stations in suburban Portland.

The TV manager, Alida Thacher, wanted a system that would grow with the studio, which she runs with the help of a staff assistant and several student interns.

"The advantage of using a computer system is your ability to purchase software upgrades rather than having to buy hardware, which our budget doesn't allow," Thacher said. "And computer editing is the way video is going."