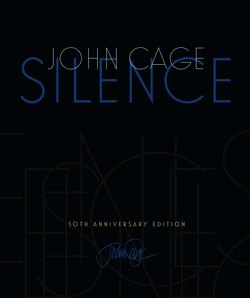

Читать книгу Silence - John Cage - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEXPERIMENTAL MUSIC: DOCTRINE

This article, there titled Experimental Music, first appeared in The Score and I. M. A. Magazine, London, issue of June 1955. The inclusion of a dialogue between an uncompromising teacher and an unenlightened student, and the addition of the word “doctrine” to the original title, are references to the Huang-Po Doctrine of Universal Mind.

Objections are sometimes made by composers to the use of the term experimental as descriptive of their works, for it is claimed that any experiments that are made precede the steps that are finally taken with determination, and that this determination is knowing, having, in fact, a particular, if unconventional, ordering of the elements used in view. These objections are clearly justifiable, but only where, as among contemporary evidences in serial music, it remains a question of making a thing upon the boundaries, structure, and expression of which attention is focused. Where, on the other hand, attention moves towards the observation and audition of many things at once, including those that are environmental—becomes, that is, inclusive rather than exclusive—no question of making, in the sense of forming understandable structures, can arise (one is tourist), and here the word “experimental” is apt, providing it is understood not as descriptive of an act to be later judged in terms of success and failure, but simply as of an act the outcome of which is unknown. What has been determined?

For, when, after convincing oneself ignorantly that sound has, as its clearly defined opposite, silence, that since duration is the only characteristic of sound that is measurable in terms of silence, therefore any valid structure involving sounds and silences should be based, not as occidentally traditional, on frequency, but rightly on duration, one enters an anechoic chamber, as silent as technologically possible in 1951, to discover that one hears two sounds of one’s own unintentional making (nerve’s systematic operation, blood’s circulation), the situation one is clearly in is not objective (sound-silence), but rather subjective (sounds only), those intended and those others (so-called silence) not intended. If, at this point, one says, “Yes! I do not discriminate between intention and non-intention,” the splits, subject-object, art-life, etc., disappear, an identification has been made with the material, and actions are then those relevant to its nature, i.e.:

A sound does not view itself as thought, as ought, as needing another sound for its elucidation, as etc.; it has no time for any consideration—it is occupied with the performance of its characteristics: before it has died away it must have made perfectly exact its frequency, its loudness, its length, its overtone structure, the precise morphology of these and of itself.

Urgent, unique, uninformed about history and theory, beyond the imagination, central to a sphere without surface, its becoming is unimpeded, energetically broadcast. There is no escape from its action. It does not exist as one of a series of discrete steps, but as transmission in all directions from the field’s center. It is inextricably synchronous with all other, sounds, non-sounds, which latter, received by other sets than the ear, oper ate in the same manner.

A sound accomplishes nothing; without it life would not last out the instant.

Relevant action is theatrical (music [imaginary separation of hearing from the other senses] does not exist), inclusive and intentionally purposeless. Theatre is continually becoming that it is becoming; each human being is at the best point for reception. Relevant response (getting up in the morning and discovering oneself musician) (action, art) can be made with any number (including none [none and number, like silence and music, are unreal]) of sounds. The automatic minimum (see above) is two.

Are you deaf (by nature, choice, desire) or can you hear (externals, tympani, labyrinths in whack)?

Beyond them (ears) is the power of discrimination which, among other confused actions, weakly pulls apart (abstraction), ineffectually establishes as not to suffer alteration (the “work”), and unskillfully protects from interruption (museum, concert hall) what springs, elastic, spontaneous, back together again with a beyond that power which is fluent (it moves in or out), pregnant (it can appear when- where- as what-ever [rose, nail, constellation, 485.73482 cycles per second, piece of string]), related (it is you yourself in the form you have that instant taken), obscure (you will never be able to give a satisfactory report even to yourself of just what happened).

In view, then, of a totality of possibilities, no knowing action is commensurate, since the character of the knowledge acted upon prohibits all but some eventualities. From a realist position, such action, though cautious, hopeful, and generally entered into, is unsuitable. An experimental action, generated by a mind as empty as it was before it became one, thus in accord with the possibility of no matter what, is, on the other hand, practical. It does not move in terms of approximations and errors, as “informed” action by its nature must, for no mental images of what would happen were set up beforehand; it sees things directly as they are: impermanently involved in an infinite play of interpenetrations. Experimental music—

QUESTION: —in the U.S.A., if you please. Be more specific. What do you have to say about rhythm? Let us agree it is no longer a question of pattern, repetition, and variation.

ANSWER: There is no need for such agreement. Patterns, repetitions, and variations will arise and disappear. However, rhythm is durations of any length coexisting in any states of succession and synchronicity. The latter is liveliest, most unpredictably changing, when the parts are not fixed by a score but left independent of one another, no two performances yielding the same resultant durations. The former, succession, liveliest when (as in Morton Feldman’s Intersections) it is not fixed but presented in situation-form, entrances being at any point within a given period of time.—Notation of durations is in space, read as corresponding to time, needing no reading in the case of magnetic tape.

QUESTION: What about several players at once, an orchestra?

ANSWER: You insist upon their being together? Then use, as Earle Brown suggests, a moving picture of the score, visible to all, a static vertical line as coordinator, past which the notations move. If you have no particular togetherness in mind, there are chronometers. Use them.

QUESTION: I have noticed that you write durations that are beyond the possibility of performance.

ANSWER: Composing’s one thing, performing’s another, listening’s a third. What can they have to do with one another?

* * *

QUESTION: And about pitches?

ANSWER: It is true. Music is continually going up and down, but no longer only on those stepping stones, five, seven, twelve in number, or the quarter tones. Pitches are not a matter of likes and dislikes (I have told you about the diagram Schillinger had stretched across his wall near the ceiling: all the scales, Oriental and Occidental, that had been in general use, each in its own color plotted against, no one of them identical with, a black one, the latter the scale as it would have been had it been physically based on the overtone series) except for musicians in ruts; in the face of habits, what to do? Magnetic tape opens the door providing one doesn’t immediately shut it by inventing a phonogène, or otherwise use it to recall or extend known musical possibilities. It introduces the unknown with such sharp clarity that anyone has the opportunity of having his habits blown away like dust.—For this purpose the prepared piano is also useful, especially in its recent forms where, by alterations during a performance, an otherwise static gamut situation becomes changing. Stringed instruments (not string-players) are very instructive, voices too; and sitting still anywhere (the stereophonic, multiple-loud-speaker manner of operation in the everyday production of sounds and noises) listening …

QUESTION: I understand Feldman divides all pitches into high, middle, and low, and simply indicates how many in a given range are to be played, leaving the choice up to the performer.

ANSWER: Correct. That is to say, he used sometimes to do so; I haven’t seen him lately. It is also essential to remember his notation of super- and subsonic vibrations (Marginal Intersection No. 1).

QUESTION: That is, there are neither divisions of the “canvas” nor “frame” to be observed?

ANSWER: On the contrary, you must give the closest attention to everything.

* * *

QUESTION: And timbre?

ANSWER: No wondering what’s next. Going lively on “through many a perilous situation.” Did you ever listen to a symphony orchestra?

* * *

QUESTION: Dynamics?

ANSWER: These result from what actively happens (physically, mechanically, electronically) in producing a sound. You won’t find it in the books. Notate that. As far as too loud goes: “follow the general outlines of the Christian life.”

QUESTION: I have asked you about the various characteristics of a sound; how, now, can you make a continuity, as I take it your intention is, without intention? Do not memory, psychology—

ANSWER: “—never again.”

QUESTION: How?

ANSWER: Christian Wolff introduced space actions in his compositional process at variance with the subsequently performed time actions. Earle Brown devised a composing procedure in which events, following tables of random numbers, are written out of sequence, possibly anywhere in a total time now and possibly anywhere else in the same total time next. I myself use chance operations, some derived from the I-Ching, others from the observation of imperfections in the paper upon which I happen to be writing. Your answer: by not giving it a thought.

QUESTION: Is this athematic?

ANSWER: Who said anything about themes? It is not a question of having something to say.

QUESTION: Then what is the purpose of this “experimental” music?

ANSWER: No purposes. Sounds.

QUESTION: Why bother, since, as you have pointed out, sounds are continually happening whether you produce them or not?

ANSWER: What did you say? I’m still—

QUESTION: I mean—But is this music?

ANSWER: Ah! you like sounds after all when they are made up of vowels and consonants. You are slow-witted, for you have never brought your mind to the location of urgency. Do you need me or someone else to hold you up? Why don’t you realize as I do that nothing is accomplished by writing, playing, or listening to music? Otherwise, deaf as a doornail, you will never be able to hear anything, even what’s well within earshot.

QUESTION: But, seriously, if this is what music is, I could write it as well as you.

ANSWER: Have I said anything that would lead you to think I thought you were stupid?