Читать книгу What the Thunder Said - John Conrad - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 This Side of Paradise

You have never seen a starry night sky until you have lifted your eyes to the heavens in northern Kandahar Province. I lay down to catch 40 winks on the wooden deck of the Arnes trailer in FOB [Forward Operating Base] Martello and was startled at the radiance and closeness of the stars all around me. I swear I could reach out and grab a handful of them. I felt I was peering into the very soul of God. We had avoided two IED attempts on our convoy up here on the endless day that was yesterday. Now set to return to KAF in less than an hour, I prayed I would not get any closer to my maker than I was right now, at least not today ...

— Lieutenant-Colonel John Conrad,

Kandahar Diary, April 2006

Warrant Officer Paul MacKinnon and Master Corporal Shawn Crowder of the National Support Element, Task Force Afghanistan’s combat logistics battalion will tell you today that it was just an ordinary sojourn in hell, a typical convoy on this strange new sort of battlefield, but 15 May 2006 became one of those marrow-sucking Kandahar days that hits a snag and then gets progressively longer. MacKinnon and Crowder were on the precarious resupply convoy to the Gumbad safe house in northern Kandahar Province when smoke began to pour out of the engine of their Bison armoured vehicle. The Bison had broken down and the convoy was split in two, with some vehicles continuing the mission so that the outpost could be resupplied. MacKinnon, Crowder, and the rest of the troops and journalists that made up this convoy fragment settled in for a dreaded long halt. The term long halt is brimming with memories and meaning for Canadian soldiers familiar with Afghanistan. It means you must wait for heavier recovery assistance; you can’t press on. The long halt recalls endless hours at the top of the world when you scrutinize the peerless blue sky of Afghanistan and watch dust devils weave their eerie paths across the broken land. A millennium can pass in an hour. A soldier on a long halt stares up at infinity while contemplating the potential horrors of the immediate. For Paul MacKinnon and Shawn Crowder a thousand years of waiting was beginning.

Gumbad is a lonely infantry platoon outpost jammed in the heart of Taliban-dominated territory. Our tour of duty was two and a half months old on 15 May and already trips to Gumbad were met with gritted teeth. Over 100 kilometres northwest of the main coalition base at KAF, the patrol house at Gumbad can only be reached using a combination of barely discernable secondary roads, dried-out riverbeds called wadis, and flat-out, cross-country driving. No matter how one looks at it there are only two meagre roads in to the patrol house — two paths offering the enemy the advantage of predictability. The spread of terrain around the patrol house is disarmingly beautiful, reminiscent of Alberta’s badlands or the raw spread of land along the Dempster Highway in Canada’s Far North. Here in northern Kandahar, however, the landscape is rife with jury-rigged munitions that can abruptly sweep away your life.

These munitions come in all shapes and sizes and are made from the most rudimentary components and are called improvised explosive devices (IEDs). It is positively eerie how basic and simply constructed many of these IEDs are. Insurgents make full use of these crudely rendered weapons and plant them like macabre crop seed on Afghanistan’s roads, culverts, and riverbeds. IEDs are the preferred weapon of the enemy for use against Canadian convoys. It was near Gumbad that one such explosive device consisting of two pairs of double-stacked anti-tank mines claimed the lives of four Canadian soldiers three weeks back on 22 April 2006.

The Canadian battle group was doggedly holding the Gumbad outpost, waiting for the arrival of Afghan authorities to share and ultimately relieve them of the task. In the meantime the job hung like an albatross around the neck of 1 Platoon, Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (1 PPCLI). The gritty Canadian infantry platoon had to be sustained by lumbering logistics trucks escorted in under the muzzles of LAV III fighting vehicles. It was murder, literally, getting up to Gumbad, and the Canadians ended up holding the rustic outpost until the end of June 2006.

Alexander the Great reputedly camped along the shores of Lake Arghandab with an army of 30,000 Greek soldiers. Today the turquoise lake stands out like a precious jewel in the stark landscape along the Tarin Kot Highway. All Canadian convoys going to the northern portion of the province — either the Gumbad Patrol House or Forward Operating Base Martello — must pass this lake.

Warrant Officer MacKinnon and Master Corporal Crowder weren’t looking at Gumbad on 15 May. You feel an IED detonation for several nanoseconds before you actually hear it. They were just settling into the defensive posture of a long halt around their disabled Bison vehicle, beginning the wait for recovery when the shock waves and subsequent noise of an enormous explosion reached them from farther up the wadi. One of the newest vehicles in the Canadian fleet, a mine-resistant RG 31 or Nyala, in the small convoy that pressed on, had struck an IED device and blown apart. The fickle hand of fate had kept the NSE soldiers out of the blast area. Had MacKinnon and Crowder not broken down they would have been the next vehicle back from the Nyala. Fortunately there were no immediate fatalities in the strike, but the wounds of the soldiers were serious.

The race against time for successful medical evacuation had begun. The problem now was that the limited recovery assets from KAF suddenly had a higher priority vehicle casualty to deal with. Back on the airfield, 100 kilometres to the south, smart operations staffs were working on stretching limited resources to get both vehicles out. MacKinnon smoked a cheap cigar as he watched the hours evaporate in the blistering 45 degree Celsius heat. He was normally part of the NSE operations team, the resilient staff that worked on problems exactly like this from KAF in tandem with the 1 PPCLI Infantry Battle Group, and he knew that whatever solution was hammered out at the enormous coalition base wouldn’t assist them anytime soon.

Another eternity had passed by the time Paul MacKinnon noted the arrival of several Afghan locals. He took his interpreter over to talk with them. They told him that they were farmers. The Afghans went on to explain that between 20 and 30 more men would be joining them from a nearby village to sleep in their fields tonight. Time stood still between two beats of MacKinnon’s heart. This wasn’t right. A streetwise Cape Breton boy, Paul MacKinnon had heard enough. He realized that the time had come for them to help themselves.

“They’re gathering,” he told Bob Weber, one of the Canadian reporters travelling with them. “They’re the wrong age and the wrong attitude.” A battlefield mechanic by trade, MacKinnon had already mapped out a rudimentary withdrawal plan in his mind in the space between his conversation with the Afghan farmer and his return to the vehicles. The goddamn Bison would be moving whether it wanted to or not. He pulled aside one of the sergeants and laid out a new course. “Sarge, we’re not staying here….”

The Canadians cabled their stricken Bison to a healthy one that had stayed with them for security reinforcement and loaded up the collection of Canadian reporters who had been toughing out the day with them. Master Corporal Crowder returned to the driver compartment and began steering the dead Bison without the benefit of power. Manually steering an armoured vehicle across Kandahar Province is a brutally physical task. Over the next 12 hours the small convoy laboured to cover the 100 kilometres back to KAF. They finally arrived back at the base in the wee hours before dawn exhausted and spent. MacKinnon described the outcome as one of the very best given the situation they had faced over the past 20 hours. Nobody died. In fact, it would be two more days before another Canadian soldier was killed in Kandahar.

Paul MacKinnon woke up later that day to discover that his greater concern was with his wife. MacKinnon was an ex-smoker who had long fought the itch to start up again. His wife, checking the day’s news on the Internet back in Edmonton, had just seen a photo that showed him smoking a huge stogie on the deck of his Bison armoured vehicle, looking all the world like the Canuck version of Sergeant Rock. Shawn Crowder woke up to find his arms on fire with pain. His limbs were purple with bruises from steering the stricken Bison back from the nether regions of the province without power steering. He dismissed any inquiries into his health with a disgusted shake of the head.

“When are we heading out again, sir?” This was the only remark he made. Discussion of yesterday was firmly closed. This was the battlefield of our generation and it didn’t care if you were a politician, a journalist or a soldier. It wouldn’t discern what cap badge or rank you wore.

I remember that when I came to KAF in January the outgoing guys were building a new monument that included pieces of the one we had in Kabul. The centrepiece was a large rock that was found near where Sergeant Short and Corporal Beerenfenger were killed around Kabul in 2003, and attached to it were plaques bearing the names of soldiers killed to date. The rock was pretty much covered and I remember thinking I hope we don’t fill up all the extra space with our soldiers’ names. We are now building a new, bigger monument.

— Major Scott McKenzie, “Afghanistan Updates”

In early August 2006 I made a point of going to the fortress-like building known as the Taliban Last Stand or TLS. TLS wouldn’t have looked out of place as a set for the canteen on planet Tatooine in George Lucas’s Star Wars films. The building is surrounded by the incessant roar of transport aircraft and choppers that feed and feed from the giant air base. Possessed of thick mud walls and prominent decorative arches alien to western architecture, TLS serves now as a multipurpose administration facility and the KAF Air Movements Terminal.1 It was supposedly the building that held the last Taliban resistance during the early invasion of Afghanistan in 2002 — Operation Enduring Freedom’s first year. As the story goes, a JDAMs missile from the U.S. Air Force ended the “last stand” with pinpoint lethality.

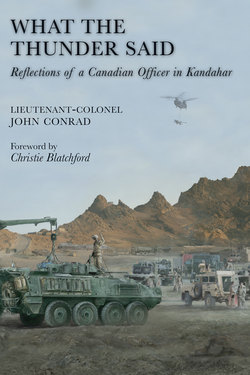

A joint NSE-1 PPCLI convoy makes its way north on the Tarin Kot Highway from KAF to begin work on Forward Operating Base Martello in early April 2006. FOB Martello eventually served as a patrol platform for Alpha Company and as a much-needed way station for Dutch forces making their way to Tarin Kot out of KAF.

Our relief in place, the term the military uses for being replaced while in contact with an enemy, was in full swing with the new NSE of the Royal Canadian Regiment’s 1st Battalion. The rotation flights home had started two weeks earlier with C-130 Hercules aircraft bringing fresh faces in the morning and ushering out bits and pieces of my unit in the afternoon. Today was the day that Sergeant Pat Jones, a professional army driver and convoy leader in my NSE, would depart KAF to begin his journey home. I had to see him off.

“Well, Jonesy, you made it,” I muttered as I patted this stalwart soldier on the back. There are no words to describe how difficult it was to see Sergeant Jones leave. But he had to. He was utterly used up, charred black on the inside.

“Yup” was all Jones could muster. He seemed surprised that I might notice his imminent departure and perplexed that I had made the effort to see him off. To that minute he never had so much as an inkling how much psychological momentum he had given to his commanding officer.

“How are you feeling?”

“Fine, sir. Fine ... just ... tired of seeing dead people.”

It was the last time I ever spoke to him.

The battlefield of the logistics soldier lies so heavily entrenched in the realm of the mind — the psychological plane. Unlike our brothers in the combat arms we rarely go on the offensive. There is no cathartic release for the logistician that an attack can permit the infantryman. The logistic soldier in Kandahar rides with passive optimism that he or she will come up swinging after the attack. But whether you live or die, whether you get to come up fighting, depends not on your physical fitness, your intellect, or your prowess with the rifle. Instead your survival hangs on such random factors as vehicle armour, proximity to the blast, and pure luck. Providence. That is hard to accept. The first move in a convoy fight belongs to the enemy and that is terrifically unsettling. Soon every Toyota that strays too close to your truck resembles a bomb, every colourful kite is a semaphore signal, and every smile from an Afghan pedestrian betrays a sinister secret. Ground convoys extract a continuous toll on the psychological reserves of a logistics unit.

We nearly lost Sergeant Pat Jones on the first week of the tour. On 3 March 2006, two days after the Canadians took the reins from the American Task Force Gun Devil and their supporting Logistics Task Force 173 in Kandahar Province, one of our convoys was attacked.

The convoy was using Highway 1 to deliver supplies and personnel to their new assignments with the Canadian Provincial Reconstruction team at Camp Nathan Smith, in Kandahar City. Ironically there was a military investigation team from Canada onboard conducting an investigation into the death of Mr. Glynn Berry from the Department of Foreign Affairs who had been killed in a convoy the month before we had arrived. Two of the passengers in Ian Hope’s LAV III were from my supply staff, Master Warrant Officer Mitch Goudreau and Sergeant Bird. Bird was a reservist, a part-timer, from the East Coast who was destined to become the main supply purchasing agent for Camp Nathan Smith. Mitch Goudreau was a well-travelled figure inside the PPCLI having come to the NSE from the magnificent 2nd Battalion in Shilo, Manitoba. Goudreau was along to see his subordinate properly introduced and installed at the camp. Two kilometres east of the city, their LAV III was attacked by a vehicle-borne suicide bomber. The vehicle had six rounds of artillery ammunition onboard when it detonated beside the LAV. In the ensuing blast the crew commander, Master Corporal Loewen, was badly hurt. Loewen’s arm was nearly completely severed and his life was in immediate peril. The Bison armoured vehicle in the column pulled up beside the LAV III and began to assist with medical triage. Sergeant Pat Jones was the vehicle crew commander.2 Jones witnessed the entire blast from his perch behind the Bison’s C6 machine gun and he followed his drills to serve as a medical evacuation platform for the LAV III casualties. A combination of Bison passengers, 1 PPCLI, and NSE soldiers provided immediate first aid to Master Corporal Loewen. Because of the proximity of KAF, the convoy commander decided to evacuate him by ground in Jones’s armoured vehicle instead of asking for air evacuation. Time in a medical evacuation is the critical factor. A handful of minutes can make the difference between life and death. Jones pushed his old Bison so hard in the urgency to get Loewen back to KAF that the vehicle’s engine burst into flames. Just a few metres shy of the main gate into the camp, smoke began to stream from the vehicle’s engine. Power evaporated from the machine and it came to an abrupt stop, maddeningly on the very doorstep of KAF.

What followed over the next few minutes is best described as barely managed chaos. Similar scenes have been played out by scores of Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan since 2006. Priority one was the badly injured Loewen who needed to keep moving forward to medical attention. Every second of delay deepened the need. As the Bison burned, the rear exit ramp jammed tight in the closed position, trapping its passengers. The top hatch of the vehicle, known lovingly as the family hatch, had to be forced open manually and Loewen was passed through and cross-loaded onto a the roof of another vehicle in the convoy, a Canadian Mercedes G-Wagon. As he was fastened securely to a stretcher, a couple of quick-thinking soldiers stood in the doors of the truck and held the stretcher firmly in place while they careened through the gate into KAF and finished the race to the Role 3 military hospital.

With Loewen again on his way, Sergeant Jones sorted through his remaining priorities and turned his attention onto the Bison driver. Corporal “Killer” Mackinnon, a military truck driver serving on his first ever tour of duty, was stuck in the driver’s compartment with eyes as wide as pie plates. He was suffering badly from the heat of the burning engine in the neighbouring cowling.

“Killer, hang in there!” was all Jones grunted as he climbed back on top of the vehicle to assist his driver. Jones pulled up hard on the back of MacKinnon’s body armour. I recall hearing about a farmer near our home in the mid-1970s who had lifted a corn harvesting wagon off of his daughter’s crushed legs in order to save her life. The adrenaline-inspired moment always harboured elements of the unbelievable in my mind until what Jones did. Lifting a man vertically out of a driver compartment is a Herculean task on a good day but Pat Jones succeeded in freeing MacKinnon on one of the worst days of his life. Although Killer MacKinnon was scared shitless, the only physical damage he suffered was minor burns and a melted pistol holster. As he turned to his next task, Jones wasn’t as lucky. The vehicle had a halon fire extinguisher system that is supposed to allow for external detonation. On this day of days the external release didn’t work. Tripping the extinguisher could only be done from inside the machine, and without so much as a “here I go!” Pat Jones re-entered the burning armoured vehicle. In the process of executing this drill and releasing the extinguishing chemical he received a lung full of halon. It would be days before he could stop coughing and hacking.

When Paddy Earles and I visited Sergeant Pat Jones later on the night of 3 March in the military hospital, I got my first real glimpse of the effects of war. Master Corporal Loewen lay bandaged and sedated across the ward. Pat Jones was sequestered inside a semi-private enclosure beside a young captain with appendicitis. He was sitting up as we came in, but something was tangibly wrong.

Pat Jones was a bear of a man. He routinely took his furlough from the army late in the year and derived great enjoyment from his annual hunting expeditions in northern Alberta. Jonesy had served as a young corporal with me when I was a company commander in Edmonton. During the workup training for Kandahar, he had been a rock of stability, a fine senior non-commissioned officer (NCO) and one of only a handful of convoy commanders we had to rely upon.

The look in his eyes that night at the KAF hospital was alien to the man I knew so well. He was careful, I thought, too careful to say all the right things. We could tell that he was unsettled, struggling hard against things unseen. The change in him shook my confidence. Every commanding officer, every leader, cultivates his core team, his “go to” men and women who can be trusted to get the job done when the going is difficult. Sergeant Pat Jones was born to be one of these men, and replacing an NCO of his calibre was next to impossible. Standing in the plywood Golgotha of the Role 3 hospital, I had my first bout of anxiety over the small size of the NSE. This was the third day of our mission. I had really screwed up.

Although I knew before we deployed that I didn’t have enough support soldiers, the fact that I might not have brought enough convoy leaders to see us through this mission never dawned on me. These sergeants are like bishops on a chessboard. They are gritty, experienced, and worth their weight in gold. Paddy Earles and I left the hospital and went for coffee at the little Canadian Exchange café behind our sea container headquarters. I was in hell that night, frightened on a host of different levels. If we could lose a man like Jones from our logistics team on day three of the mission, what would the next six and a half months bring?

We didn’t lose him. His lungs cleared of halon, and the faraway look in his eyes ebbed. If the haunting new tone in his voice didn’t completely go away, it at least waned to a point where it could no longer be easily detected and he returned to duty later that same week. General Rick Hillier presented Jones with a Chief of the Defence Staff Coin, followed later by the commendation, for his actions on 3 March 2006. What Jones probably didn’t know was that by his courage both beyond the wire and inside the KAF Role 3 hospital, he had restored my confidence. I was, after all, a rookie to real war. The NSE had been tested, our soldiers had been hurt, and we were dusted off and back to work the next day. For reasons that even to this day I don’t understand, this incident was pivotal. It galvanized me for the darker storms yet to come.

We got your phone message. We hope to leave it on the machine till you’re back. Your dad and I love you and pray for your safe return.

— First Letter from My Parents, 10 February 2006