Читать книгу What the Thunder Said - John Conrad - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

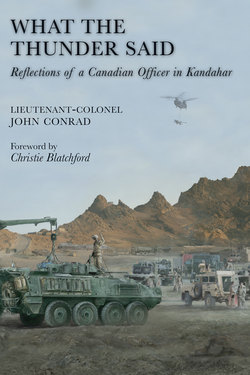

ОглавлениеFOREWORD by Christie Blatchford

I still think of John Conrad as a native Newfoundlander, and probably always will. It is my experience that the most passionate and articulate Canadians come from that hard place, and from the first time I interviewed him, and he described the modern battlefield as akin to “water droplets on a walnut table, with the droplets the safe haven,” I nearly fainted with pleasure at his use of the language. What the Thunder Said proves the point: John has brought his passion for logistics and shown how in the war in Afghanistan combat happens anywhere and everywhere, putting virtually every soldier, whether infantry or truck driver, squarely on the front line and smack in the midst of the fight.

Logistics and passion, even to those in the reborn Canadian Army (though not to anyone who served in Kandahar in the spring and summer of 2006), may seem a bit of an oxymoron. Arguably no branch of the Canadian Forces (CF) suffered more than logistics during what former Chief of Defence Staff General Rick Hillier used to call “the decade of darkness,” when slashing budgets and numbers were the order of the day. Certainly, no other arm of the forces went so unappreciated, even by those who ought to have known better.

And no other group was so seriously undervalued for so long and then called upon to do so much when the CF returned to all-out combat that summer.

Just how unique was that particular tour in Afghanistan is still not very well understood by many back home.

To many Canadians, the war in Afghanistan seems all of a piece, one summer pretty much indistinguishable from another — there are always deaths, sombre ramp ceremonies, shots of soldiers sweating in that barren moonscape.

But the summer of 2006 was different.

As some elements of the battle group led by the 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, were in close-quarter gunfights every day, others were daily travelling hundreds of kilometres over bomb-laden roads (I use the term loosely) to keep them supplied with bullets, water, and rations, while back at Kandahar Air Field, still others worked 10-hour shifts in the sweltering heat of unglamorous tented workshops to keep the machinery humming.

As John told me once, the light armoured vehicles and others that logged two million old-fashioned miles that tour on Afghanistan’s rutted river wadis and rugged ground were going through axles and differentials like popcorn.

Where now Canadian troops stick largely to the fertile areas west of Kandahar City, in those days they also moved to the farthest-flung parts of Kandahar Province, their own area of operations; several times rode to the rescue of the British in nearby Helmand Province; and oversaw the safe movement of Dutch soldiers into Uruzgan Province.

It was an astonishing demonstration of Canadian competence and resolve, and none of it would have been possible without the National Support Element (NSE), the small unit John commanded.

It was these men and women who kept what John calls the mobile Canadian Tire store on the road, and did it with far less armour and protection than their heavily armed peers in the infantry.

I remember a story Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Hope, the battle group commander, once told me. An infantry officer who was escorting in a resupply convoy complained about the man’s sloppy driving. Lieutenant-Colonel Hope went over to the NSE sergeant in charge and asked how long they’d been on the road.

Four days, he replied.

Ian Hope was gobsmacked. As he said, “I realized just to what extent John [Conrad] was driving his people to keep us supplied.”

John’s book is about those unsung men and women who lived up to the ancient motto of soldiers who maintain supply lines and the tools of warfighting. It’s Arte et Marte, Latin for “by skill and by fighting.” In the summer of 2006, they proved they could do both. They did it without complaint — to be fair, they didn’t have time to complain — and mostly unnoticed.

This book rectifies that. And because it’s written by John Conrad, a soldier-poet, it does so beautifully.